National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

A mere land mass of around 720 km2, Singapore is a small, densely populated island city-state which became a sovereign republic with a parliamentary democracy on 9 August 1965. It was founded in 1819 as a trading port by Sir Stamford Raffles of the British East India Company and attained self-government between 1959 and 1963 before merging with Malaya, Sarawak, and Sabah to form the Federation of Malaysia.

The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. It provides for a popularly elected, non-executive president as the head of state vested with specific custodial powers, a Prime Minister (as head of government) and a Cabinet of Ministers, and a unicameral Parliament. Parliamentary elections, under universal adult suffrage and compulsory voting, must be held at least every five years. The leader of the political party that secures the majority of seats in Parliament will be asked by the President to become the Prime Minister (PM) who in turn will select his Ministers from elected legislators to form the Cabinet.

Modelled on the Westminster system and buttressed by the doctrine of the separation of powers, the Government comprises three branches: the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary.[1] This doctrine has been judicially recognised in Singapore:[2] “All Constitutions based on the Westminster model incorporate the principle of Separation of Powers as part of their constitutional structure”.[3] The Legislature, which is the primary law-making institution, is made up of Parliament and the elected president. Administering the laws is the Executive which is made up of the president and the Cabinet, the latter of which is responsible for the general direction of the Government and accountable to Parliament. The Judiciary interprets the laws and adjudicates in legal disputes. Singapore’s legal system has its roots in English common law and practice.

With independence, there has been a gradual – and increasing – movement towards developing an autochthonous legal and political system that is relevant and unique to its political, social and economic circumstances. The guiding principle is that the adoption of any legal practice or norm must be compatible with Singapore´s cultural, social and economic requirements. In this regard, the economic success of Singapore can be attributed, among others, to strong political leadership and the rule of law to build a new society and to entrench its economic survival while ensuring that the legal system is attuned to the needs and demands of the international community.

1.1. Demographics, ethnic groups, languages and religions

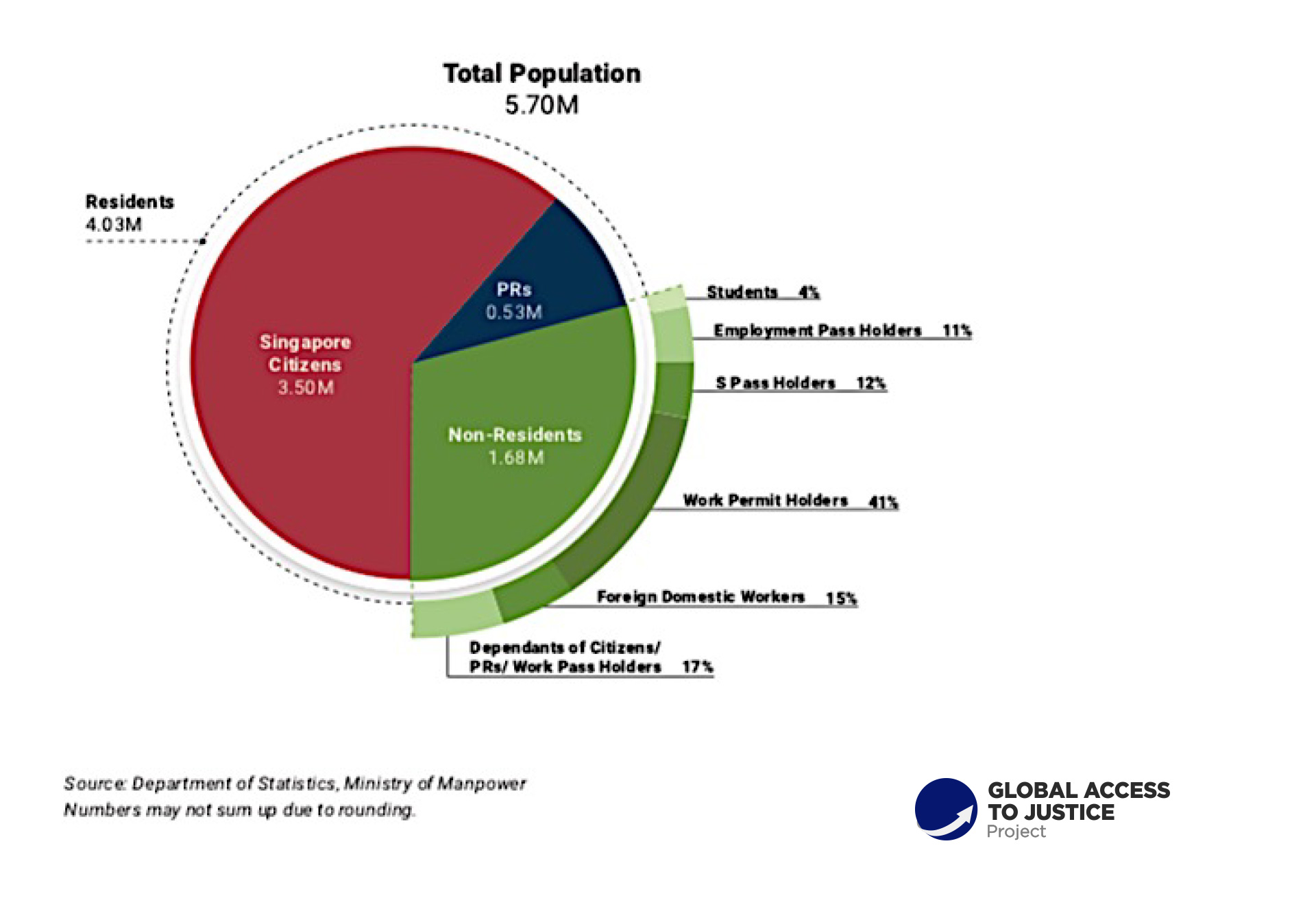

As of June 2019, Singapore’s population stood at 5.7 million comprising 3.5 million citizens, 0.53 million permanent residents, and 1.68 million non-residents. Between June 2018 and June 2019, the citizen population grew by 0.8 per cent. The citizen population continues to age, with 16 per cent aged 65 years and above, compared with 15.2 per cent in 2018. Immigration remains a key plank of Singapore’s population policy, augmenting the low birth rates of the citizen population. International marriages, in which one spouse is a non-citizen, comprise about 30 to 40 per cent of all marriages registered in Singapore.

The non-resident population grew by 2.0 per cent, to reach 1.68 million as of June 2019. This increase was due largely to foreign employment growth driven by sustained growth in the services sector and the turnaround in the construction sector. By work pass type, foreign employment growth was mainly driven by an increase in work permit holders (often unskilled or low-skilled workers).

Chart 1. Singapore’s population

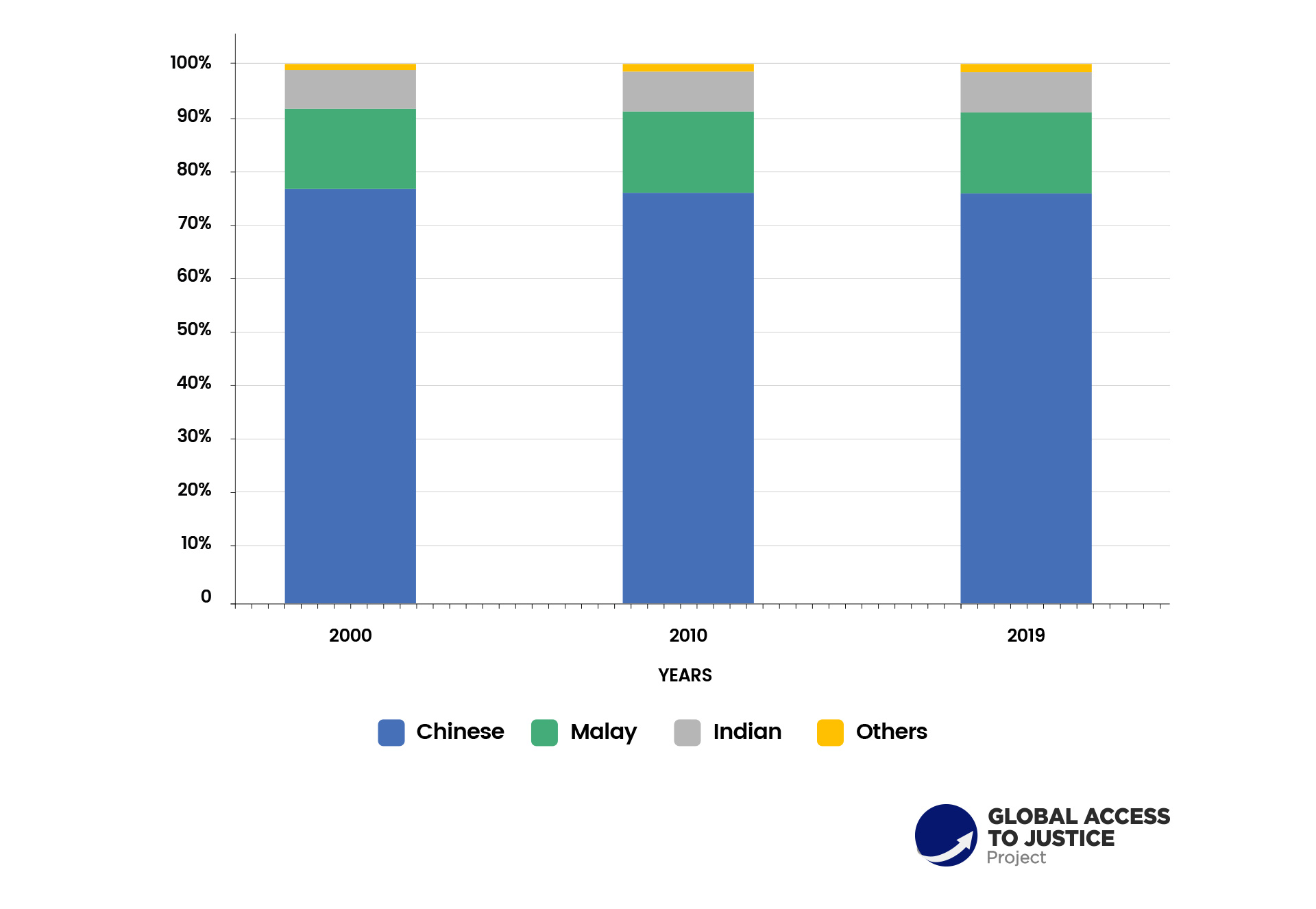

Singapore is a multi-racial nation-state. The proportion of the various races in Singapore’s citizen population has remained stable for much of the twentieth century, particularly since independence. As the majority community, the ethnic Chinese constitute about three-quarters of the citizen population. The Malays, recognized constitutionally as the indigenous people of Singapore, make up 15 per cent of the population.[4] The Indians are about 8 per cent of the population. The government is committed to maintaining the long-standing racial composition of the citizen population. Such a racial balance is believed to have contributed to Singapore’s social stability and its multiracial character. Inter-racial marriages constitute about 20 to 25 per cent of all marriages registered in Singapore.

Singapore is a multi-racial nation-state. The proportion of the various races in Singapore’s citizen population has remained stable for much of the twentieth century, particularly since independence. As the majority community, the ethnic Chinese constitute about three-quarters of the citizen population. The Malays, recognized constitutionally as the indigenous people of Singapore, make up 15 per cent of the population.[4] The Indians are about 8 per cent of the population. The government is committed to maintaining the long-standing racial composition of the citizen population. Such a racial balance is believed to have contributed to Singapore’s social stability and its multiracial character. Inter-racial marriages constitute about 20 to 25 per cent of all marriages registered in Singapore.

Chart 2. Race distribution

Right from the outset of Singapore attaining self-government from the British in 1959, there is a prima facie parity among the four official languages (viz Malay, Tamil, Mandarin, and English). Language equality clearly recognises Singapore’s multi-racial, multi-religious, and multi-lingual make-up as requiring careful management and the nurturing of trust and confidence among the different communities and between the government and the people. The Malay language is also the sole national language. This was and is an important symbolic political gesture recognising the Malays as the indigenous people of Singapore and the geopolitical realities in Singapore’s locale. This state of affairs is provided for in Article 153A of the Singapore Constitution, which proclaims that:

Right from the outset of Singapore attaining self-government from the British in 1959, there is a prima facie parity among the four official languages (viz Malay, Tamil, Mandarin, and English). Language equality clearly recognises Singapore’s multi-racial, multi-religious, and multi-lingual make-up as requiring careful management and the nurturing of trust and confidence among the different communities and between the government and the people. The Malay language is also the sole national language. This was and is an important symbolic political gesture recognising the Malays as the indigenous people of Singapore and the geopolitical realities in Singapore’s locale. This state of affairs is provided for in Article 153A of the Singapore Constitution, which proclaims that:

(1) Malay, Mandarin, Tamil and English shall be the 4 official languages in Singapore.

(2) The national language shall be the Malay language and shall be in the Roman script:

Provided that —

(a) no person shall be prohibited or prevented from using or from teaching or learning any other language; and

(b) nothing in this section shall prejudice the right of the Government to preserve and sustain the use and study of the language of any other community in Singapore.[5]

Singapore’s national anthem and motto, Majulah Singapura (“Onward Singapore”), are both rendered in Malay. Military parade commands are issued in Malay and the Prime Minister begins the National Day Rally, his most important address to Singaporeans, in Malay.

Since independence, English is dominant as the language of education, commerce, and government. English was, of course, introduced by the British. During the colonial regime, English was the language for the colonial administrators and the small privileged population who had the opportunity of learning the language. English can be regarded as the surrogate lingua franca of Singaporeans. It did not ostensibly provide any racial group, including the ethnic Chinese majority, with any linguistic advantage. This choice of the English language was not only politically pragmatic but shrewd.

Besides being multiracial and multilingual, Singapore’s multi-religious composition character is also another important manifestation of its diversity. In April 2014, Pew Research Centre ranked Singapore is ranked as the world’s most religious diverse country or territory.[6]

| Changing Religious Demography: Percentage Distribution of Resident Population aged 15 and over by Religion, 1980-2010[7] | ||||

| Religion | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

| Buddhism | 26.7 | 31.1 | 42.5 | 33.3 |

| Taoism | 30.0 | 22.4 | 8.5 | 10.9 |

| Islam | 16.2 | 15.4 | 14.9 | 14.7 |

| Christianity | 9.9 | 12.5 | 14.6 | 18.3 |

| Hinduism | 3.6 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 5.1 |

| Other religions | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| No religion | 13.1 | 14.3 | 14.8 | 17.0 |

Singapore’s Constitution provides for every person the right to profess, practise, and propagate his religion. While faith-inspired views are not excluded from the public domain, the Singapore government has sought to keep the public square and the religious realm separate even if the walls between them are not always watertight. Although secularism is a cardinal principle of political governance, the separation of religion and state is not found in Singapore’s Constitution. In Singapore’s context, secularism is broadly understood as the governance principle of separating religion and state, and of the state being neutral vis-à-vis the various religious faiths and between religion and non-religion. There is no official religion in Singapore. At the same time, there is also no anti-establishment constitutional provision either. So fundamental is the freedom of religion that Emergency ordinances promulgated under Article 150 of Constitution shall not validate any provision inconsistent with “the provisions of this Constitution relating to religion, citizenship or language.”

In recognition of the special position of the Malays who are the indigenous people of Singapore, Article 152 of the Constitution provides that:

(1) It shall be the responsibility of the Government constantly to care for the interests of the racial and religious minorities in Singapore.

(2) The Government shall exercise its functions in such manner as to recognise the special position of the Malays, who are the indigenous people of Singapore, and accordingly it shall be the responsibility of the Government to protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote their political, educational, religious, economic, social and cultural interests and the Malay language.

Limited legal pluralism is also facilitated by Article 152 and embedded in Singapore’s British-based common law legal system through some community autonomy for the indigenous Malay-Muslim community. In areas of Muslim personal law such as marriage, divorce and inheritance, Article 153 of the Singapore Constitution provides that, “The Legislature shall by law make provision for regulating Muslim religious affairs and for constituting a Council to advise the President in matters relating to the Muslim religion”. In turn, the Administration of Muslim Law Act (AMLA) (Cap. 3) is the main legislation by which Muslim religious affairs are regulated and by which the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS), a statutory board, is constituted to advise the President and the government in matters relating to the Muslim religion. Article 153 is the only constitutional provision in which a religion is specifically mentioned.

1.2. Gross domestic product (GDP)

| Year | Per Capita GDP (USD) | Per Capita GNI (USD) |

| 2010 | 46727 | 47237 |

| 2011 | 52034 | 53886 |

| 2012 | 53077 | 55547 |

| 2013 | 53899 | 56967 |

| 2014 | 55560 | 57563 |

| 2015 | 51850 | 55647 |

| 2016 | 52775 | 56724 |

| 2017 | 56112 | 60306 |

| 2018 | 60205 | 64567 |

1.4. Human development indicators

1.4.1. Gross national income (PPP)

In 2018, Singapore’s gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP) was USD 83,793.

1.4.2. Inequality index and poverty line

Singapore does not have an official poverty line. The Government’s approach is to use broad definitions for the groups it seeks to help, set clear criteria to identify and assess those in need, and come up with tailored schemes. It regards a poverty line as not fully reflecting the severity and complexity of issues faced by the poor. It may also lead to those above the poverty line missing out on assistance. Singapore’s assessment process for providing help to those in need is rigorous but also flexible to cater to the genuinely needy. This means that those who do not meet certain criteria in help programmes are also able to receive assistance. The Government also conducts regular reviews to ensure that social assistance provided to low-income families remains relevant to the low-income and vulnerable.

Singapore’s Gini coefficient[8], based on household income from work per household member, was 0.452 in 2019, compared to 0.458 in 2018. After adjusting for government transfers, which includes Workfare[9] and Goods and Services Tax credits, the Gini coefficient was 0.398.[10] This reflects the redistributive effect of Government transfers.[11] Singapore’s Gini coefficient was 0.442 in 2000 and 0.454 in 2001. It last peaked in 2007 at 0.482.[12]

1.4.3. Life expectancy at birth

In 2020, life expectancy at birth was 83.9 years.[13]

1.4.4. Expected and mean years of schooling

In 2018, expected years of schooling was 16.3 years while the mean years of schooling was 11.5 years.

1.4.5. Human development index (HDI)

In 2019, Singapore’s HDI was ranked eleventh in the world and in the “very high human development” category. Between 1990 and 2019, Singapore’s HDI value increased from 0.721 to 0.938, an increase of 30.1 percent.[14]

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

As a common law legal jurisdiction, the roots of Singapore’s legal system can be found in the English legal system. Singapore’s legal system has evolved over the years, building on its common law origins established by the British colonial administration. But legal autochthony is the hallmark of independent Singapore’s legal system and essential to the rule of law. The sources of law include the Constitution (and related constitutional instruments), primary legislation, subsidiary legislation, common law, and international law.[1]

The Singapore Judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, State Courts, and Family Justice Courts. The Supreme Court consists of the High Court and the Court of Appeal and hears both criminal and civil cases.[2] The High Court consists of the General Division of the High Court (“General Division”) and the Appellate Division of the High Court (“Appellate Division”). The Singapore International Commercial Court is a division of the General Division”.[3] The Court of Appeal is the apex court.[4]

The State Courts comprise the District Courts, Magistrates’ Courts, Coroners’ Courts, Small Claims Tribunals, Employment Claims Tribunals, and the Community Disputes Resolution Tribunals.[5] In 2014, the Subordinate Courts were renamed as the State Courts, the Chief District Judge re-designated as the Presiding Judge of the State Courts (this position is held by a High Court Judge or a Judicial Commissioner), and the minimum statutory requirements for appointment as District Judges and Magistrates were raised.[6] The main intent was to raise the standing of the State Courts to better reflect their primary position within the judicial system, and to strengthen their quality. The bulk of cases (90 percent) litigated are dealt with by the State Courts, which the Chief Justice has described as “the gateway into the justice system for the vast majority of litigants”.[7]

Within the State Courts, there are specialised courts such as the Coroners’ Courts and the Community Courts.[8] The Coroner’s Court holds inquiries into the death of a person when there is reason to suspect that a person has died in an unnatural manner, by violence, when the cause of death is unknown or in situations where the law requires an inquiry. The Community Court deals with special cases involving community resources and adopts a problem-solving approach to special categories of cases. Such cases include:

- Youthful offenders (aged 16 to below 21);

- Offenders with mental disabilities;

- Neighbourhood disputes;

- Attempted suicide cases;

- Family violence cases;

- Carnal connection offences committed by youthful offenders;

- Abuse and cruelty to animals;

- Cases which impact on race relations issues;

- Selected cases involving offenders aged 65 years and above.

The Family Justice Courts (FJC), headed by a Presiding Judge, comprise the Family Division of the High Court, the Family Courts, and the Youth Courts.[9] The FJC came into operation in October 2014 and brings together all family-related legal matters under a specialised body of courts, judges, and other family practitioners (like social workers, counsellors, probation officers) to better address the needs of families and youths in distress.

A measure of limited legal pluralism is provided for in the establishment of the Syariah Court to administer Muslim law in specified personal matters such as those relating to Muslim marriages, divorce, and inheritance.[10] The Syariah Court has jurisdiction throughout Singapore to hear and determine all actions and proceedings in which all parties are Muslims or where the parties were married under the provisions of Muslim law and which involve disputes relating to (a) marriage; (b) divorces known in the Muslim law as fasakh, khuluk and talak; (c) betrothal, nullity of marriage or judicial separation; (d) the disposition or division of property on divorce or nullification of marriage; or (e) the payment of emas kahwin, marriage expenses (hantaran belanja), maintenance and consolatory gifts or mutaah.[11]

2.1. Civil Cases

The District Courts hear civil actions where the disputed amount does not exceed SGD250,000 or, in the case of road traffic accident claims or claims for personal injuries arising out of industrial accidents, does not exceed SGD500,000.[12] Parties may also agree, by a signed memorandum, to have the matter heard by the District Court, even though the sum in dispute exceeds the monetary limit of the jurisdiction of a District Court.[13] The Magistrates’ Courts can hear civil actions where the disputed amount does not exceed SGD60,000.[14]

The Small Claims Tribunals have jurisdiction to hear a small range of civil claims not exceeding SGD20,000, or SGD30,000 if the claimant and respondent consent in writing.[15] The Small Claims Tribunals provide a quick and inexpensive forum for the resolution of small claims disputes arising out of sale of goods and provision of services, as well as other types of small value claims. To further this objective, lawyers are not allowed to represent any party in proceedings before the Tribunals.[16]

The High Court hears cases in the first instance as well as cases on appeal from the State Courts. Its jurisdiction is as follows:[17]

• Civil cases where the claim exceeds SGD250,000

• Probate matters if the estate exceeds SGD5,000,000

• Ancillary matters in family proceedings where assets equal SGD5,000,000 or more.

The Singapore International Commercial Court is a division of the General Division of the High Court and part of the Supreme Court of Singapore designed to deal with transnational commercial disputes.[18]

2.2. Criminal Cases

The Magistrates’ Courts have the jurisdiction and power to try any offence for which the maximum term of imprisonment provided by law does not exceed 5 years or which is a fine-only offence.[19]

The District Courts have the jurisdiction and power to try any offence for which the maximum term of imprisonment provided by law does not exceed 10 years or which is a fine only offence.[20] However, their jurisdiction may be enlarged in certain circumstances.[21]

Notwithstanding the foregoing, a Magistrate Court’s sentencing jurisdiction is (in general) limited to: (a) imprisonment not exceeding 3 years, (b) a fine not exceeding SGD10,000, and (c) caning not exceeding 6 strokes.

The District Court’s sentencing jurisdiction (in general) is limited to: (a) imprisonment not exceeding 10 years, (b) fine not exceeding SGD30,000, and (c) caning not exceeding 12 strokes.[22] However, where the law expressly provides for it, the Magistrates’ Court and the District Court also have the jurisdiction to impose sentences which exceed the above limits.

The High Court is empowered to try all cases, and may pass any sentence authorised by law.[23]

2.3. Appellate Courts

The General Division of the High Court hears appeals from the decisions of Family Courts, District Courts and Magistrate’s Courts in civil and criminal cases, and decides on points of law reserved by special cases submitted by these courts.[24] In addition, the General Division of the High Court has general supervisory and revisionary jurisdiction over all subordinate courts in civil and criminal matters.[25] Appeals from decisions of the General Division will lie either in the Appellate Division (within the High Court) or the Court of Appeal.[26] The Appellate Division generally exercises civil jurisdiction only[27], and is generally constituted by three or any greater odd number of Judges.[28] Certain decisions of the Appellate Division may, with the leave of the Court of Appeal, be further appealed to the Court of Appeal.[29]

The Court of Appeal is Singapore’s apex court, and exercises both civil and criminal jurisdiction. The Court of Appeal is generally constituted by three or any greater odd number of Judges.[30] The Court of Appeal has the power to order the transfer of appeals between the Appellate Division and the Court of Appeal. [31]

2.4. The Legal Profession in Singapore

The legal profession in Singapore is a fused one: A qualified person is admitted to the Singapore Bar as an “advocate and solicitor of the Supreme Court”. Singapore-qualified lawyers require a practising certificate issued by the Supreme Court of Singapore. Foreign-qualified lawyers (as well as Singapore-qualified lawyers practising in foreign law practice entities) require registration with the Legal Services Regulatory Authority (LSRA), a department under the Ministry of Law.[32]

All lawyers must be attached to and registered under a law practice, for which there are both local and foreign law practices, and different forms of law practice entity and collaboration licences in these categories: Singapore Law Practices, licensed Foreign Law Practices, Qualifying Foreign Law Practices[33], Joint Law Ventures, Formal Law Alliances, Group Practices and Representative Offices.[34]

The extent to which each type of lawyer can practise Singapore law depends on whether they are admitted to the Singapore Bar and the extent to which the law practice entity they are practising in is allowed to practise Singapore law. For example, Singapore-qualified lawyers practising in Singapore Law Practices can practise the full ambit of Singapore law, whereas foreign-qualified lawyers practising in Foreign Law Practices can only practise foreign law.

Non-lawyers who are employees of a firm (i.e. regulated non-practitioners registered under section 36G of the Legal Profession Act) are allowed to cumulatively hold not more than 25% of the total value of equity interests in the Singapore law practice. The threshold requirements are found in the Legal Profession (Law Practice Entities) Rules 2015. At the moment, non-lawyer ownership levels in law practices are generally low.[35]

The number of licensed practicing lawyers in the country (as of 31 Dec 2020):

| Type of Lawyer Registration | Number |

| Registered Foreign Lawyers | 1,246 |

| Singapore lawyers | 6,162 |

| Total | 7,408 |

2.4.1. The Law Society of Singapore

The Law Society of Singapore is established under Part V of the Legal Profession Act. Besides being statutorily responsible for professional practice, conduct and discipline, it carries out various statutory functions, including[36]:

- Maintaining and improving the standards of conduct and learning of the legal profession in Singapore;

- Facilitating the acquisition of legal knowledge by members of the legal profession;

- Assisting the Government and the courts in matters affecting legislation submitted to it, and the administration and practice of law in Singapore;

- Representing, protecting and assisting members of the legal profession in Singapore; promoting in any manner the Society thinks fit the interests of the legal profession in Singapore;

- Protecting and assisting the public in all matters ancillary or incidental to the law; and

- Making provision for or assisting in the promotion of a scheme whereby impecunious persons on non-capital charges are represented by lawyers.

The mission of the Law Society is to serve its members and the public by sustaining an independent bar which upholds the rule of law and ensures access to justice. As part of its mission in ensuring access to justice for the needy, the Law Society has established a Pro Bono Services Office. The Council of the Law Society, which consists of 5 statutory members and elected members, manages the affairs of the Law Society and ensures the proper performance of its functions under the Legal Profession Act.

Every Singapore lawyer who has in force a Singapore practising certificate is automatically a member of the Law Society.[37] Certain categories of foreign lawyers registered with the Legal Services Regulatory Authority are also automatically members of the Law Society, or can apply to be associate members of the Law Society.[38]

2.4.2. Singapore Academy of Law

In addition, there is the Singapore Academy of Law, a statutory body established in 1988.[39] The Academy undertakes statutory functions such as stakeholding services, law reporting, and the appointment of Senior Counsel, Commissioners for Oaths and Notaries Public. The Academy is led by a Senate headed by the Chief Justice, and comprising the Attorney-General, the Supreme Court Bench, and key leaders of the law schools and various branches of the legal profession. All persons who are called as advocates and solicitors of the Supreme Court (whether practising or not) or appointed as Legal Service Officers, corporate counsel, faculty members of the three local law schools, and foreign lawyers in Singapore are required by law to be members.

2.5. Legal Representation

For civil cases, legal representation is not mandatory unless a party is a body corporate (a company, a limited liability partnership or an unincorporated association other than a partnership or registered trade union).[40] Such parties must be represented by lawyers in court proceedings unless the court grants leave for an officer of the body corporate to represent them.

The Singapore legal system and the judicial process is aware of more individuals as litigants-in-person – an individual who choose to conduct his own case in court, i.e., act in person. Litigants in person are held to the same standard of preparation and conduct that lawyers must follow. This includes complying with all the relevant laws and procedures. The court will not re-litigate a previously decided action.

For criminal cases, Art 9(3) of Singapore’s Constitution safeguards the right to legal counsel. It provides that where a person is arrested, he shall be informed as soon as may be of the grounds of his arrest and shall be allowed to consult and be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice (see Section 3.1 on Criminal Procedure).

For both civil and criminal cases, legal aid and assistance are available from Government-funded legal aid schemes as well as non-Government partners such as the Law Society Pro Bono Services (LSPBS), the Community Justice Centre (CJC), and other community, religious and voluntary welfare organisations (see Section 4 on Access to Justice and Section 5 on Legal Aid System).

2.6. Paralegals

In Singapore, “paralegals” do not fall within the purview of the Legal Profession Act. In the local context, “paralegal” refers to and includes a legal executive, legal secretary or legal clerk and any other employee of a law practice, who performs paralegal functions and assists a solicitor as a paralegal, who does not have in force a practising certificate and is without regard to the designation of such employee.

Sections 29, 32 and 33 of the Legal Profession Act (“LPA”) prohibit persons without a valid practising certificate from practising law in Singapore and such persons fall within the category of “unauthorised persons” under the LPA. Paralegals working across law practices in Singapore also fall within the category of “unauthorised persons”. They are not allowed to practise law as an advocate and solicitor. Rule 8(1) of the Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules requires a solicitor to exercise proper supervision over his employees and other staff at all times.[41]

2.7. The Singapore Judiciary

Article 93 of the Singapore Constitution states that “The judicial power of Singapore shall be vested in a Supreme Court and in such subordinate courts as may be provided by any written law for the time being in force”. Reinforced by the constitutional doctrine of the separation of powers and through judicial review in constitutional law and administrative law, the Judiciary ensures the accountability of the Legislature and the Executive in their law-making and administrative decisions and actions.

As of 24 March 2021, there are 26 Judges (including the Chief Justice, 4 Justices of the Court of Appeal, 3 Judges of the Appellate Division of the High Court), 4 Judicial Commissioners, and 3 Senior Judges on the Supreme Court bench.[42] There are 16 other International Judges.[43]

2.7.1. Judicial Independence in Singapore

The courts are independent of and co-equal to the other branches of Government. Part VIII of the Constitution safeguards judicial independence. In a 2010 article, then Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong described the role of the judiciary in a democracy as well as the centrality of judicial independence in the judiciary’s execution of its constitutional duties thus:

In a democracy with a form of representative government (based on the doctrine of separation of powers), the Judiciary is one of three arms of government, co-equal in status, and vested with the power, among others, to check the Legislature and the Executive in their exercise of powers vested in them by law and the constitution of the State. Its other primary function is to adjudicate disputes between people and disputes between the people and the State or agencies of the State. The Judiciary acts as an impartial referee to decide what conduct is permissible or not permissible under applicable rules of conduct, whether the rules have been infringed or not infringed, and to provide the remedies for such infringements. To fulfil these functions, the Judiciary has to be independent of the other two arms of government. A Judiciary that is not independent would not be able to fulfil such a role, and would provide a weak foundation for democracy and its associated attribute (ie, the rule of law) to flourish. Conversely, the Judiciary requires the existence of the rule of law for continuous independence. There cannot be the rule of law without an independent Judiciary, and vice versa, but with both, there will be security, law and order, and stability, which are requisites for progress and the protection of political and civil rights.[44]

The Chief Justice and the Supreme Court Judges are appointed by the President if he, acting in his discretion, concurs with the advice of the Prime Minister: Art 95(1) of the Singapore Constitution. A person appointed under Art 95(1) shall hold office until he attains the age of 65; or such later time not being later than six months after he attains that age, as the President may approve: Art 98(1).

The President may, if he, acting in his discretion, concurs with the advice of the Prime Minister, appoint a person who is 65 years of age or older and who is either qualified for appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court or has ceased to be a Judge of the Supreme Court, to be the Chief Justice, a Judge of Appeal or a Judge of the High Court for a specified period: Art 95(2).

Under Art 95(4) of the Constitution, the President may also, if he, acting in his discretion, concurs with the advice of the Prime Minister, appoint:

- A person who is qualified for appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court to be a Judicial Commissioner of the Supreme Court;

- A person who has ceased to be a Judge of the Supreme Court to be a Senior Judge of the Supreme Court; or

- A person who, in the opinion of the Chief Justice, is a person with the necessary qualifications, experience and professional standing to be an International Judge of the Supreme Court.

For the purposes of Art 95(4), a Judicial Commissioner, a Senior Judge or an International Judge of the Supreme Court may (a) be appointed to hear and determine a specific case only (subject to clause (10) for an International Judge); or (b) be appointed for a specified period: Art 95(5).

2.7.2. Safeguards for judicial independence

The Singapore Constitution also provides for several safeguards against political interference in the Judiciary. First, a key custodial power of Singapore’s elected President is his discretionary power to veto key public office appointments. Under Article 22(1) of the Constitution, the President, acting in his discretion, may refuse to make an appointment to the office or to revoke any appointment such as the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, and the Judicial Commissioners, Senior Judges and International Judges of the Supreme Court.[45]

Second, the removal of a person holding office as a Judge of the Supreme Court or a Judicial Commissioner, a Senior Judge or an International Judge of the Supreme Court, can only be effected on the limited ground of “misbehaviour or of inability, from infirmity of body or mind or any other cause, to properly discharge the functions of his office”: Article 98(3), 98(4) and 98(5).

A tribunal of peer Judges will determine whether the case for removal as provided for in the Constitution has been made out. The President shall appoint a tribunal, consisting of not less than 5 persons who hold or have held office as a Judge of the Supreme Court, or persons who hold or have held equivalent office in any part of the Commonwealth, and shall refer that representation to it. Only where the tribunal recommends the removal of the person from office can the Judge be removed from office.

In addition, Parliament shall by law provide for the remuneration of the Judges of the Supreme Court and the remuneration and other terms of office (including any pension or gratuity) of a Judge of the Supreme Court shall not be altered to his disadvantage after his appointment: Article 98(6), 98(7) and 98(8).

Fourth, the Constitution also restricts parliamentary discussion of the conduct of a Judge of Supreme Court except on a substantive motion of which notice has been given by not less than one-quarter of the total number of the Members of Parliament. Where a matter is under consideration or awaiting decision by a court of law, reference should not be made in Parliament to matters which are sub judice.[46]

2.7.3. State Courts Judges

In the subordinate courts, however, State Courts judges and magistrates do not enjoy security of tenure as they are public service officers in the Singapore Legal Service. However, under Article 111(3) of the Constitution, the Legal Service Commission (LSC) is constitutionally vested with the powers to appoint, confirm, emplace on the permanent establishment, promote, transfer, dismiss and exercise disciplinary control over officers in the Legal Service. In this regard, the LSC is tasked with ensuring the independence, impartiality and integrity of the subordinate courts.

The Legal Service Commission is constituted under Part IX of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore. Article 111(1) of the Constitution provides that the Commission’s jurisdiction shall extend to all officers in the Singapore Legal Service. Article 111(2) and Article 111(2A) of the Constitution provides that the LSC shall consist of the Chief Justice, as President; the Attorney-General; the Chairman of the Public Service Commission (“PSC”); and at least three but not more than six other members, each of whom shall be appointed by the President of Singapore if he, acting in his discretion, concurs with the advice of the person nominating the member(s), based on the following arrangements:

(i) At least one but not more than two persons nominated by the Chief Justice;

(ii) At least one but not more than two persons nominated by the Chairman of the PSC; and

(iii) At least one but not more than two persons nominated by the Prime Minister.

If the Chief Justice, the Chairman of the PSC or the Prime Minister, as the case may be, nominates two persons, at least one must be a person who has, for an aggregate period of not less than ten years, been a qualified person within the meaning of section 2(1) of the Legal Profession Act. These Members of the LSC shall hold office for such period as the President may specify (being not shorter than three years and not longer than five years) and be eligible for re-appointment.

2.8. The Public Prosecutor

The Attorney-General plays the key role as the Public Prosecutor. Section 11 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 2012 Rev Ed) (“CPC”) provides that the Attorney-General shall be the Public Prosecutor, with control and direction of all criminal prosecutions and proceedings under Singapore law. The prosecutorial function is completely divested from the Cabinet, and constitutionally vested solely in the Attorney-General.

Under Art 35(8) of the Constitution, the Attorney-General has the power, exercisable at his discretion, to institute, conduct or discontinue any proceedings for any offence. He acts independently in deciding who to prosecute, and what charges to bring.[47] The Attorney-General, in his capacity as the Public Prosecutor, is “the guardian of the people’s rights, including the rights of the accused”.[48]

The office of Attorney-General is established by and protected under the Constitution. The Attorney-General is appointed by the President, acting in his discretion, concurring with the advice of the Prime Minister, from among persons who are qualified for appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court: Art 35(1) of the Constitution. Under Article 22(1) of the Constitution, the elected President, acting in his discretion, may refuse to make (or to revoke) an appointment as Attorney-General if he does not concur with the advice or recommendation of the Prime Minister.

The Attorney-General (AG) performs a critical role in advancing the rule of law. As the chief legal advisor to Government and drafter of laws, the AG advises Government on how to govern and advance its policy objectives within the framework of the rule of law. In his capacity as Public Prosecutor, the AG is responsible for administering even-handed and fair criminal justice by conducting all criminal prosecutions independently of Government. The Attorney-General’s Chambers also represents Singapore at international negotiations and dispute settlement proceedings, and acts as the central authority for mutual legal assistance in criminal matters and extradition.

The Attorney-General may only be removed from office by the President if the President, acting in his discretion, concurs with the advice of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister must not tender such advice except for inability of the Attorney-General to discharge the functions of his office (whether arising from infirmity of body or mind or any other cause) or for misbehaviour and except with the concurrence of a tribunal consisting of the Chief Justice and two other Judges of the Supreme Court nominated for that purpose by the Chief Justice: Art 35(6) of the Constitution. His remuneration is determined by the President and cannot be amended to his disadvantage during his tenure: Arts 35(11), (12) of the Constitution.

The Attorney-General holds a high constitutional office equal in status with that of the Judiciary.[49] The exercise of prosecutorial discretion is subject to judicial review only on grounds of abuse and contravention of constitutional protections and rights.[50]

Past Attorneys-General have attested to the fact that Cabinet Ministers and officials in the Civil Service are respectful of the independence of the Attorney-General and do not seek to influence his prosecutorial decisions.[51]

The Attorney-General may be appointed for a specific period, and shall vacate his office upon the expiration of that period, unless he is removed with cause. Otherwise, the Attorney-General shall hold office until he attains the age of 60. However, the President (if she, acting in her discretion, concurs with the advice of the Prime Minister) may permit an Attorney-General who has attained the age of 60 to remain in office for such fixed period as may have been agreed between the Attorney-General and the Government: Art 35(4)(b) of the Constitution.

The offices of Deputy Attorneys-General are also established by the Constitution. The Deputy Attorney-General is appointed by the President, acting in his discretion, concurring with the advice of the Prime Minister, from among persons who are eligible for appointment as an Attorney-General: Art 35A(1) of the Constitution. Like the Attorney-General, he may only be removed with cause: Art 35A(9), (10) of the Constitution; and his terms of service may not be altered to his disadvantage during his term in office: Art 35A(12) of the Constitution.

A Deputy Attorney-General holds office until the end of the specific period he is appointed for (without prejudice to re-appointment); or if no period is so specified, until he attains the age of 60: Art 35A(6) of the Constitution. The President may, on the advice of the Prime Minister, permit a Deputy Attorney-General who has attained the age of 60 to remain in office for such fixed period as may be agreed between the Deputy Attorney-General and the Government: Art 35A(7) Constitution.

Officers from the Crime Division of the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) are empowered to act as Deputy Public Prosecutors (DPPs) and Assistant Public Prosecutors (APPs) under the authority of the Public Prosecutor. There are duties inherent to the role of the prosecutor. Prosecutors are more than advocates and solicitors. They are “‘ministers of justice’ assisting in the administration of justice (see R v Banks [1916] 2 KB 621 at 623)”.[52] The apex court stated that:

The duty of prosecutors is not to secure a conviction at all costs. It is also not their duty to timorously discontinue proceedings the instant some weakness is found in their case. Their duty is to assist the court in coming to the correct decision. Although this assistance often takes the form of presenting evidence of guilt as part of the adversarial process, the prosecutor’s freedom to act as adversary to defence counsel is qualified by the grave consequences of criminal conviction. The certainty required by the court before it will impose these consequences is recognised in the presumption of innocence enjoyed by the accused. For this reason, a decision to prosecute in the public interest must be seen as compatible with a willingness to disclose all material that is prima facie useful to the court’s determination of the truth, even if it is unhelpful or even detrimental to the Prosecution’s case.[53]

The Court of Appeal has stated that, “The Prosecution acts at all times in the public interest. In that light, it is generally unnecessary for the Prosecution to adopt a strictly adversarial position in criminal proceedings”.[54] Justice Steven Chong (as he then was) speaking extra-judicially to Legal Service Officers and Assistant Public Prosecutors on 10 November 2011 put it in these terms:

The accused, the Court and the community are entitled to expect that in performing his function in presenting the case against an accused person, the Prosecutor will act with fairness and detachment with the sole and unadulterated objective to establish the whole truth in accordance with the law. … The role of the Prosecutor therefore excludes any notion of winning or losing a case. … His role is to seek and achieve justice, and not merely to convict. The role is to be discharged with an ingrained sense of dignity and integrity.[55]

2.9. Availability of Legal Services

Singapore’s legal services sector has grown steadily over the years. The nominal value-added (VA) of the sector increased by more than 40%, from $1.61 billion in 2010 to $2.31 billion in 2020. During the same period, the value of legal services exported from Singapore grew by about 80% from $528 million to an estimated $947 million. Singapore’s efforts to further grow the legal sector are continuing. For instance, in early 2017, the Working Group on Legal and Accounting Services under the Committee on the Future Economy recommended steps to further develop Singapore as a global exchange for financing, brokering, structuring, and dispute resolution for international commercial transactions.[56]

Through prudent planning of manpower needs and the gradual liberalisation of the legal sector in Singapore, there is no shortage of legal services in Singapore. The government seeks to promote Singapore’s development in international legal services and dispute resolution. With the establishment of the Singapore International Commercial Court, the Singapore International Mediation Centre and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre, the objective is to offer a comprehensive suite of dispute resolution options to support the needs of business. To this end, and to ensure the adequate provision of legal services, the government ensures that there is a reliable and sufficient supply of lawyers trained at the three local law schools.

In addition, there are ongoing measures to strengthen the entire professional training regime to ensure that the quality of training remains robust and the process for accessing training opportunities remains fair, regardless of economic conditions. As the Committee for the Professional Training of Lawyers noted of the importance of professional training in the provision of legal services: “Ultimately, these are the means by which the profession can be assured that future generations of lawyers are imbued not only with sound technical skills, but also the right professional values”.[57] In other words, the emphasis must be about ensuring that the legal professionals and legal services remain relevant, resourceful, and robust.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

3.1.1. Criminal Investigation

Generally, officers of the Singapore Police Force are responsible for the investigation of criminal offences. Information first received about alleged criminal offences is recorded in first information reports.[1] In addition, other law enforcement agencies are authorised under specific legislation to investigate certain types of offences. For example, officers of the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) are empowered to investigate drug offences under the Misuse of Drugs Act (Cap 185, 2008 Rev Ed); officers of Singapore Customs are empowered to investigate customs offences under the Customs Act (Cap 70, 2004 Rev Ed). All corruption offences under the Prevention of Corruption Act (Cap 241, 1993 Rev Ed) are investigated by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB), a government agency under the Prime Minister’s Office, operating with functional independence and helmed by a Director who reports directly to the Prime Minister.[2]

Certain legislation also empower officers of regulatory agencies to investigate regulatory offences. For example, officers of the National Environment Agency can investigate environmental offences under the National Environment Agency Act (Cap 195, 2003 Rev Ed) and Environmental Public Health Act (Cap 95, 2002 Rev Ed).

The relevant law enforcement agency may commence investigations into the complaint or police report if there is reason to suspect that an offence may have been committed. As part of the investigations, the law enforcement agency will interview witnesses, including the suspect(s) or accused person(s), and also gather documentary, scientific, forensic and physical evidence, if necessary. If the investigations reveal that there is no evidence or insufficient evidence to show that an offence has been committed, no further action will be taken against the suspect. If there is sufficient evidence to prove that an offence has been committed, action may be taken against the suspect, for instance, the suspect may be given a warning or charged in court.[3]

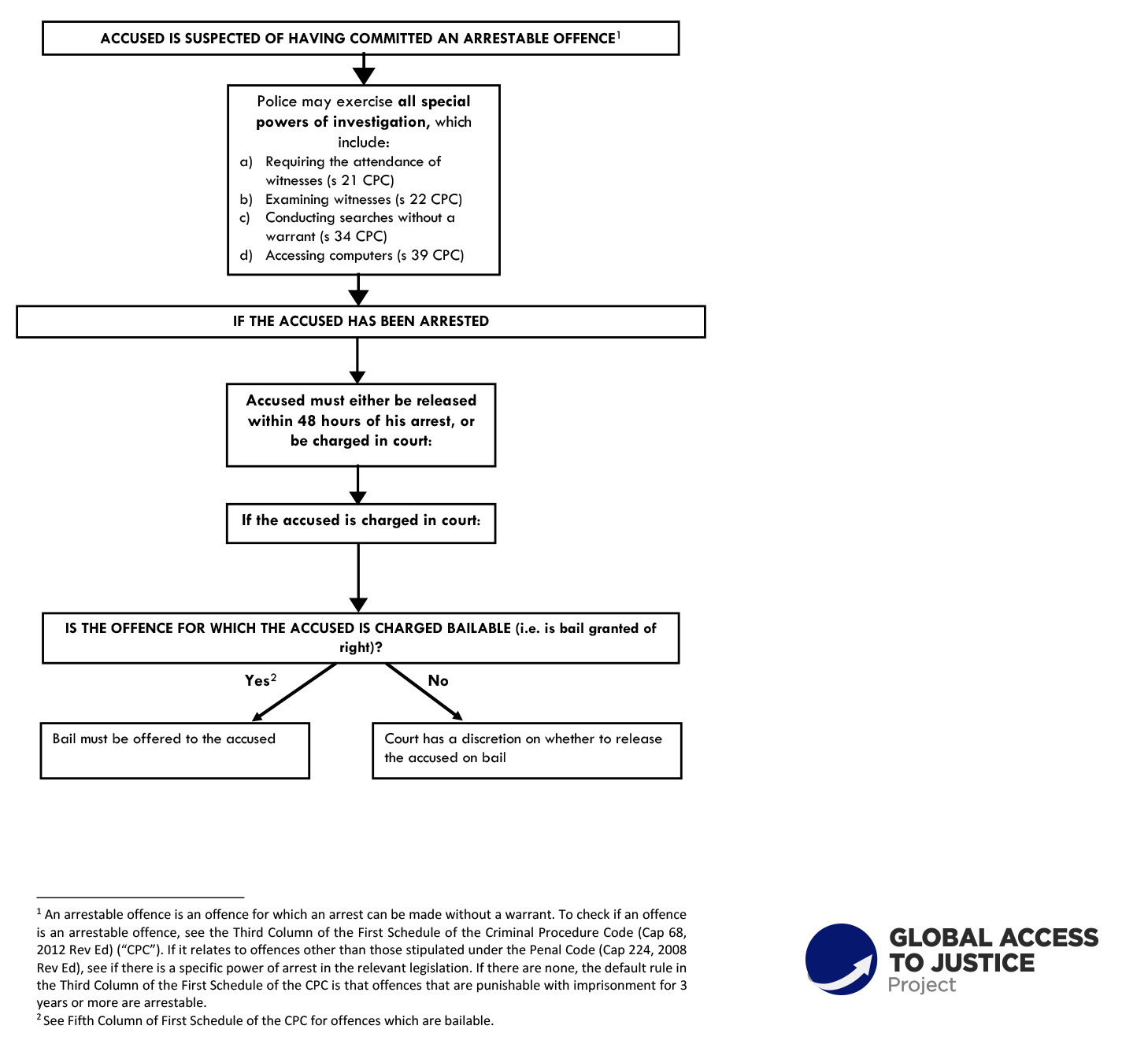

To assist them in investigations, the police have powers to compel production of documents or things (s 20 of the CPC), examine witnesses (ss 21 and 22 of the CPC), conduct searches (ss 24 to 34 of the CPC, ss 77 to 78 of the CPC) and seize property (s 35 of the CPC). Police officers can exercise powers of arrest under the CPC. Part VI (Division 1) of the CPC sets out the circumstances in which a police officer may arrest a person without a warrant.[4] Part VI (Division 2) of the CPC covers arrest with a warrant.

Under the CPC, a suspect who is arrested must generally be brought before the relevant court without unnecessary delay: ss 67 and 74 of the CPC. A person who is arrested without a warrant shall not be detained in custody for a longer period than under all the circumstances of the case is reasonable and such period shall not exceed 48 hours, exclusive of the time necessary for the journey from the place of arrest to the Magistrates’ Court: s 68 of the CPC. In this regard, Article 9(4) of the Singapore Constitution provides: “Where a person is arrested and not released, he shall, without unreasonable delay, and in any case within 48 hours (excluding the time of any necessary journey), be produced before a Magistrate, in person or by way of video-conferencing link (or other similar technology) in accordance with law, and shall not be further detained in custody without the Magistrate’s authority”. Other specific pieces of legislation also empower other law enforcement agents to make arrests. For example, s 15 of the Prevention of Corruption Act (Cap 241, 1993 Rev Ed) empowers the Director or a special investigator of the CPIB to arrest a person who is reasonably suspected of being concerned in an offence under the said Act without a warrant.

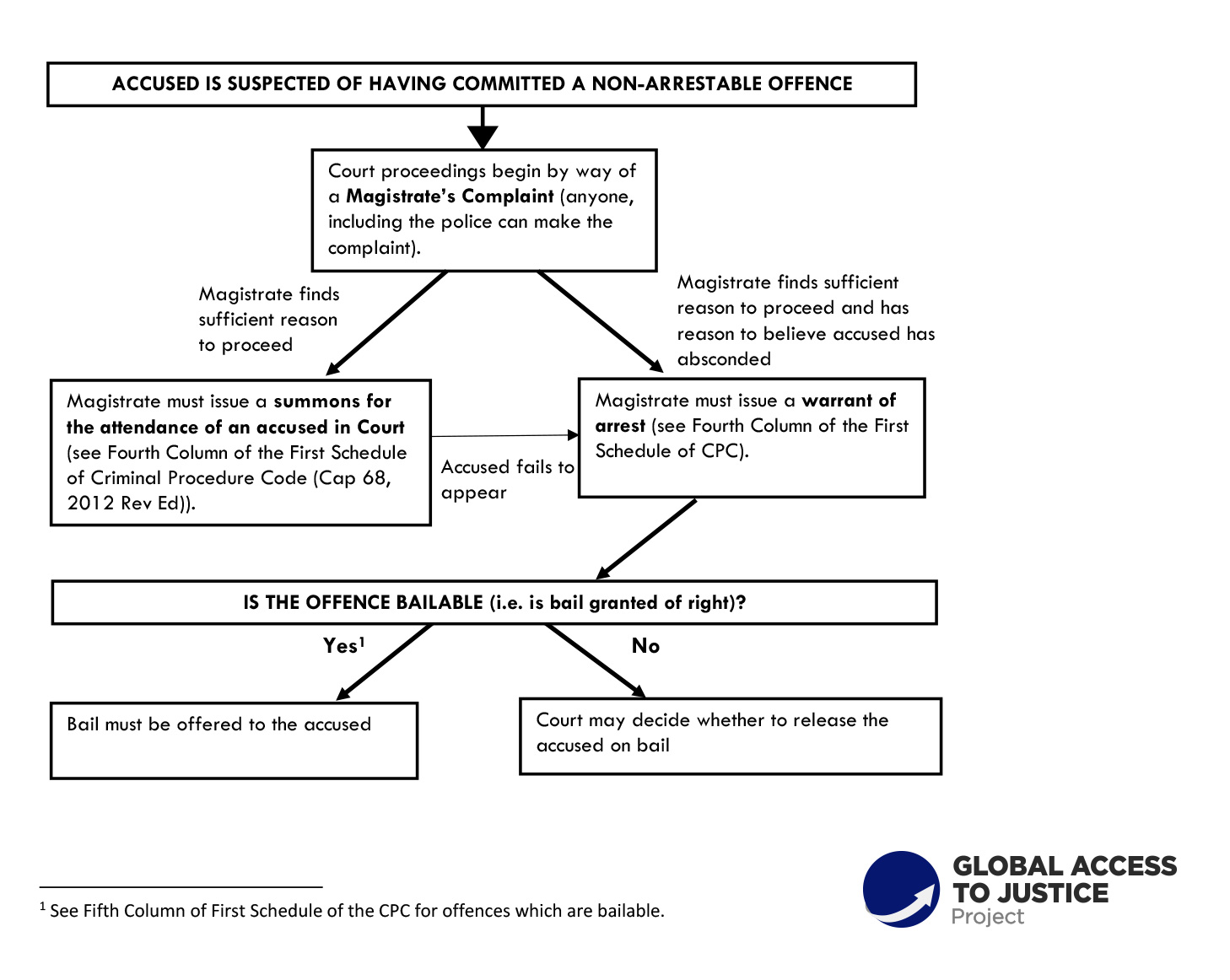

Two brief flowcharts setting out the procedure of the commencement of criminal investigations against an accused are annexed hereto.

Chart 3. Commencement of investigations (arrestable offence)

(1) An arrestable offence is an offence for which an arrest can be made without a warrant. To check if an offence is an arrestable offence, see the Third Column of the First Schedule of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 2012 Rev Ed) (“CPC”). If it relates to offences other than those stipulated under the Penal Code (Cap 224, 2008 Rev Ed), see if there is a specific power of arrest in the relevant legislation. If there are none, the default rule in the Third Column of the First Schedule of the CPC is that offences that are punishable with imprisonment for 3 years or more are arrestable.

(1) An arrestable offence is an offence for which an arrest can be made without a warrant. To check if an offence is an arrestable offence, see the Third Column of the First Schedule of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 2012 Rev Ed) (“CPC”). If it relates to offences other than those stipulated under the Penal Code (Cap 224, 2008 Rev Ed), see if there is a specific power of arrest in the relevant legislation. If there are none, the default rule in the Third Column of the First Schedule of the CPC is that offences that are punishable with imprisonment for 3 years or more are arrestable.

(2) See Fifth Column of First Schedule of the CPC for offences which are bailable.

Chart 4. Commencement of investigations (non-arrestable offence)

(1) See Fifth Column of First Schedule of the CPC for offences which are bailable.

(1) See Fifth Column of First Schedule of the CPC for offences which are bailable.

3.1.2. Criminal Prosecution

The law enforcement agencies investigate into the alleged offences and submit their investigation papers and recommendations to the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC). The decision to prosecute or not is for the Attorney-General, in his role as the Public Prosecutor, to make. The Public Prosecutor’s decision to prosecute or not to prosecute is brought solely on the basis of the law, and his assessment of the public interest. Prosecutorial discretion is exercised to advance the public interest.[5]

The prosecutorial function is constitutionally vested in the Attorney-General. Under Art 35(8) of the Constitution, the Attorney-General has the power, exercisable at his discretion, to institute, conduct or discontinue any proceedings for any offence. Section 11 of the Criminal Procedure Code provides that the Attorney-General shall be the Public Prosecutor, with control and direction of all criminal prosecutions and proceedings.

The Attorney-General/Public Prosecutor can delegate the exercise of prosecutorial powers. The Deputy Attorney-General assigned by the Attorney-General to have control and direction of criminal prosecutions and proceedings under the CPC or any other written law has all the powers of the Public Prosecutor.[6] Deputy Public Prosecutors and Assistant Public Prosecutors can be appointed by the Public Prosecutor to carry out the duties of the Public Prosecutor.[7]

Private individuals may also conduct their own prosecutions in summary cases before a Magistrate’s Court for any offence for which the maximum term of imprisonment provided by law does not exceed three years or which is punishable with a fine only.[8] Where a person wishes to initiate a private prosecution for offences outside the scope allowed under s 11(10) of the CPC, he may be permitted to do so by the Public Prosecutor via a fiat issued under s 12 of the CPC.

In general, criminal proceedings are heard inter partes, that is, in the presence of the accused and/or his counsel (where he is represented). The court may proceed to hear and determine a complaint of a criminal offence in the accused’s (and his counsel’s) absence in narrow circumstances set out in s 156 of the CPC. There are safeguards for such ex parte proceedings: there is a requirement for sufficient notice to be given to the accused, and a power for the court to declare that the ex parte proceedings are void. The court must declare the proceedings void only if the accused proves, on a balance of probabilities, that he was unaware of the summons or notice to attend court as well as the ex parte proceedings, and provided the application to declare the ex parte proceedings declared void was made within 21 days after the accused first knew of either of the summons or notice to attend court or of the ex parte proceedings.

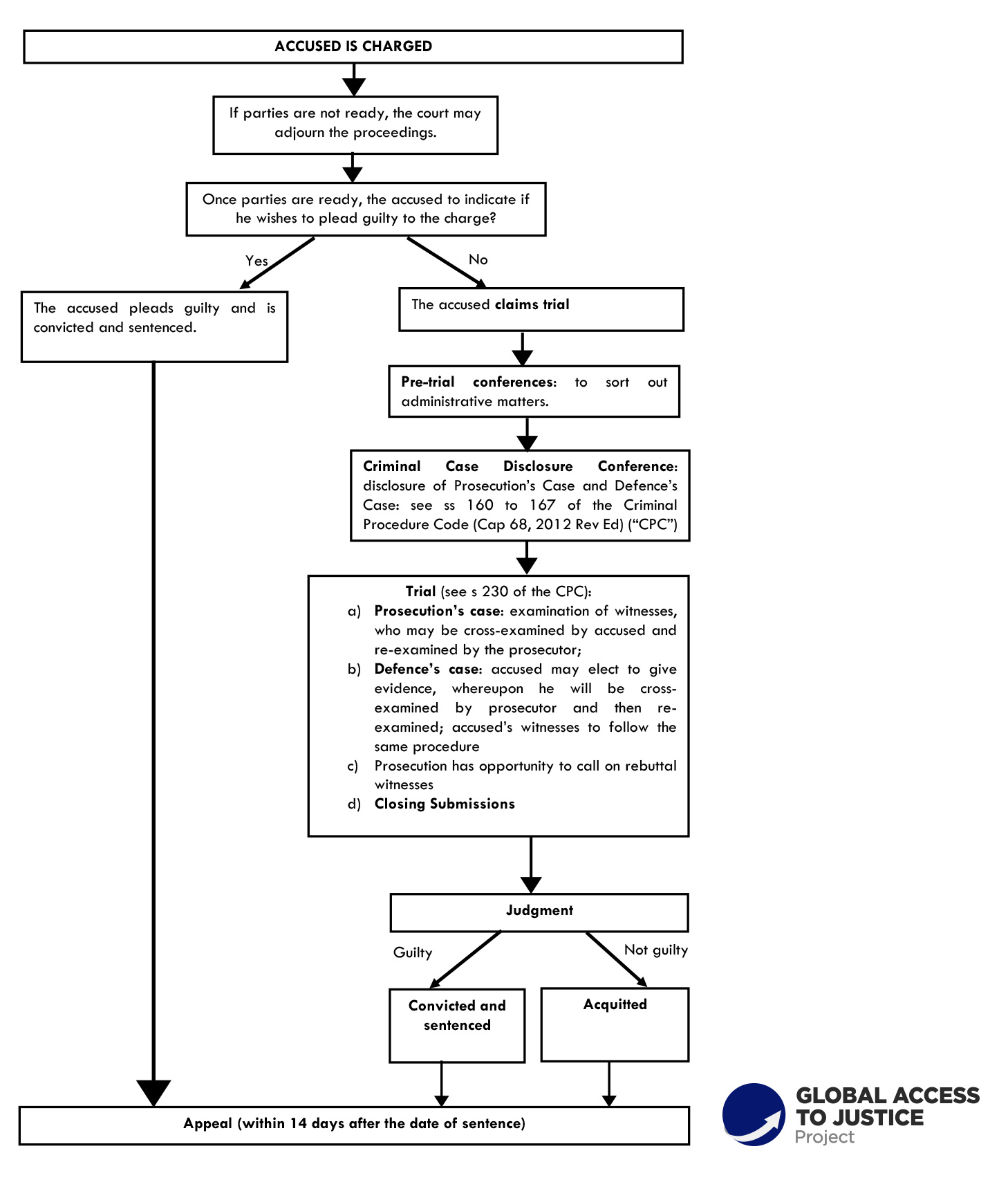

In addition, the CPC sets out some other narrow exceptions to the general requirement for an accused’s attendance at a criminal proceeding. For example, ss 232(3)–(4) allow a court to grant a complete discharge to the accused on the application of the Public Prosecutor in the absence of the accused. A brief flowchart setting out the procedure of the commencement of criminal proceedings against an accused is annexed hereto.

Chart 5. Commencement of court proceedings

According to the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2020, Singapore ranked 12th (out of 128 countries) globally for the rule of law, with an overall score of 0.79 (out of 1, with 1 indicating the strongest adherence to the rule of law).[9] For criminal justice in particular, Singapore was placed 6th globally, with a score of 0.79. Under the breakdown of this score, Singapore had a score of 0.74 for the sub-factor of “due process of law”. In addition, according to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators for 2017, Singapore was ranked in the 97th percentile for the rule of law, and 98th percentile for control of corruption.[10]

According to the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2020, Singapore ranked 12th (out of 128 countries) globally for the rule of law, with an overall score of 0.79 (out of 1, with 1 indicating the strongest adherence to the rule of law).[9] For criminal justice in particular, Singapore was placed 6th globally, with a score of 0.79. Under the breakdown of this score, Singapore had a score of 0.74 for the sub-factor of “due process of law”. In addition, according to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators for 2017, Singapore was ranked in the 97th percentile for the rule of law, and 98th percentile for control of corruption.[10]

To further strengthen the criminal justice framework, the Criminal Justice Reform Act 2018 (No. 19 of 2018) was enacted in 2018. One key aspect of the framework is the establishment of the Criminal Procedure Rules Committee, chaired by the Chief Justice, pursuant to s 428A of the Criminal Procedure Code. Comprising representatives from the Judiciary, the Bar, and the Government, the committee is tasked with regulating and prescribing the procedure and practice in Singapore’s criminal courts. This committee has the power to make court-related procedural rules to keep the court process nimble and up-to-date in the face of changing conditions. The initial contributions are also expected to be promulgated in 2021.

3.2. Civil Procedure

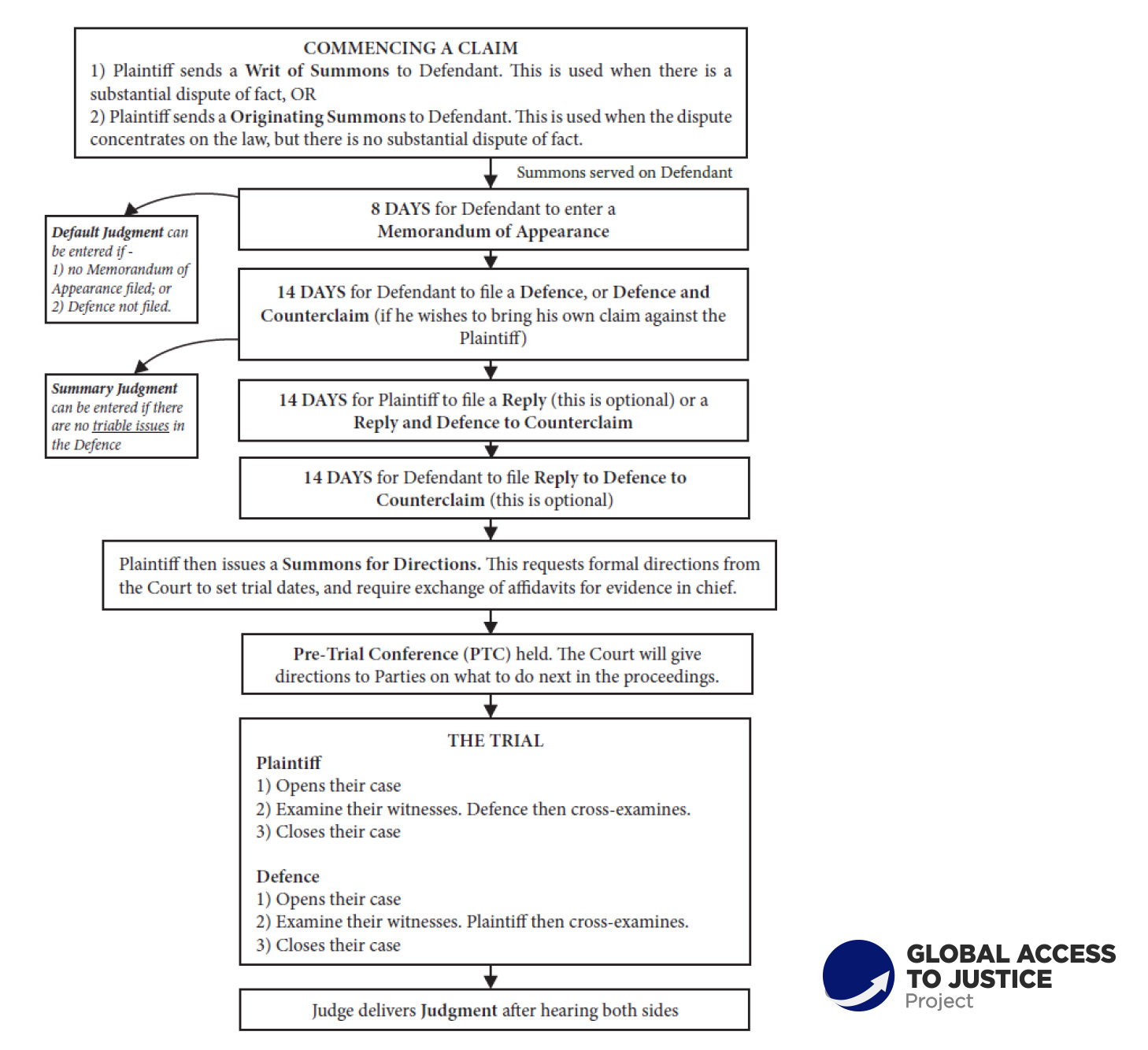

There are two ways, or originating processes, by which civil proceedings may be commenced. The first is by way of a writ of summons (Writ), which is utilised where there are substantial disputes over the facts of the case. The other method is by way of originating summons (OS). An OS is utilised where (i) the dispute is centered on legal issues and there are no substantial disputes of fact, or (ii) it is prescribed by law (e.g. pursuant to Section 124(1) of Building Maintenance and Strata Management Act, it is clearly mentioned that all applications made to the court under the said Act must be commenced by originating summons only).

Where a Writ is filed, a Plaintiff must file and serve the Writ and statement of claim on the Defendant. If the Defendant wishes to contest the claim in a Writ, he must file a memorandum of appearance after receiving the Writ and thereafter file and serve his defence on the Plaintiff. The Defendant may make a counterclaim in the same action and will then, in that event, file a defence and counterclaim. A Plaintiff may then file and serve a Reply (and defence to counterclaim, if any) as a response.

The Court will, thereafter, by way of exercising its case management powers, or pursuant to the application of parties, give directions on the various administrative and/or procedural matters leading up to trial. These include setting the time for parties to disclose and exchange documentary evidence, requiring parties to make requests for additional documents, if necessary, and the filing of the affidavits-of-evidence-in-chief of the witnesses (factual or expert). The scope of documents that must be disclosed and witness evidence that may be tendered are limited to those that are relevant to the issues in dispute between parties as discerned from the pleadings and necessary for the fair disposal of the matter and/or for saving costs.

Once the interlocutory matters are resolved and the matter is ready for trial, the case is fixed for trial before a judge. Typically, the plaintiff presents its case first followed by the defendant. Witness evidence in civil trials is usually introduced by way of written witness statements (known as affidavits of evidence-in-chief or “AEICs”). The opposing party then cross-examines the witness on any of the matters arising in the case. The party who introduced the witness has a right to re-examine the witness to clarify answers given in the course of cross-examination. After trial, parties submit written closing submissions following which the Judge who presided over the trial will render a decision.

The litigation system in Singapore is adversarial, which means parties are solely responsible in discharging their burden of proof according to their pleaded cases; judges generally do not actively seek evidence on their own initiative nor do they depart from the four walls of the pleadings.

Chart 6. Summary of the writ procedure[11]

There are mechanisms that encourage parties to resolve their disputes through settlement — alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are discussed in section 3.3. Apart from those mechanisms, the procedural rules on costs also incentivise parties to seriously consider settlement before trial.

There are mechanisms that encourage parties to resolve their disputes through settlement — alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are discussed in section 3.3. Apart from those mechanisms, the procedural rules on costs also incentivise parties to seriously consider settlement before trial.

A. Simplified Civil Process for Magistrate’s Court claims

A simplified civil process applies to Magistrate’s Court claims filed on or after 1 November 2014: see O 108 of the Rules of Court. Parties to a District Court action filed on or after 1 November 2014 may also opt into the simplified process by consent. The simplified process features upfront disclosure of documents together with early and robust case management, with the primary aim being to facilitate early resolution of the dispute. Parties are required to file and serve a list of documents with their pleadings to give parties early information of each other’s cases to facilitate early assessment.

A Case Management Conference (CMC) will generally be convened about 50 days after the Defence is filed. Prior to the CMC, parties are to exchange proposals and negotiate with a view to settling the matter at the earliest opportunity. At the CMC, the Court will help parties to identify and narrow the issues, deal with relevant interlocutory matters, fix timelines to manage and control the progress of the case and assist parties to settle the whole or part of the case.[12] Applications for summary judgment, discovery and interrogatories are excluded[13] and the Court will manage these aspects of a case at the CMC along with other interlocutory matters. In cases where parties require expert evidence to be adduced, a single joint expert is to be appointed. The evidence of the single joint expert is subject to cross-examination by parties.

Every case dealt with at a CMC may be referred for the most appropriate mode of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) where either the parties consent to use ADR for the resolution of their dispute or the Court is of the view that referral to ADR would facilitate the expeditious resolution of the dispute.[14]

If parties are unable to resolve their dispute and the case has to proceed to trial, the CMC judge will give directions for either a simplified trial or a full trial. Simplified trials are conducted with specific time limits being given to parties allocated for examination, cross-examination and re-examination for each witness and closing submissions.[15]

B. Court’s discretion in ordering costs

The court, when exercising its discretion as to costs to be awarded to parties at the end of proceedings shall take into account, where appropriate, the parties’ conduct in relation to any attempt at resolving the cause or matter by mediation or any other means of dispute resolution.[16] While this is just one of the factors to be considered by the courts when making an order for costs, it has the effect of encouraging parties to attempt dispute resolution, at the very least, with a view to obtaining a favourable costs order at the end of proceedings.

To this end, the Supreme Court Practice Directions provide that a party may make an offer, in the prescribed form, for the dispute to be referred to ADR.[17] The offer may be made at any time during proceedings and the opposing party must formally respond within 14 days[18] or else that party will be “deemed to be unwilling to attempt ADR without providing any reasons”.[19]

C. Offers to settle

The civil procedure rules also encourage parties to attempt settlement through the exchange of offers to settle.[20] One party may make an offer to the other party at any time of the proceedings before the court gives judgment. If the offeree does not accept the offer and eventually receives a judgment that is a poorer outcome than what was offered, the offeror may be compensated by costs starting from the time the offer was made.

3.2.1. External perceptions of Singapore civil justice system

Besides being known for being efficient and the impressive case management, external perception of Singapore civil justice system is positive, which attests to the effort to instill a high regard for the rule of law in the civil realm. For instance, the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2020 ranked Singapore 6th worldwide and 1st in Asia in respect of civil justice. The Rule of Law Index assessed:

- whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice system;

- whether civil justice systems are accessible and affordable as well as free of discrimination, corruption, and improper influence by public officials;

- whether court proceedings are conducted without unreasonable delays and if decisions are enforced effectively; and

- the accessibility, impartiality, and effectiveness of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

Similarly, Singapore has also been consistently ranked among the top two countries in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business survey. In 2020, it was ranked second after New Zealand. A high ease of doing business ranking means the regulatory environment is more conducive to the starting and operation of a local firm. Indicators include the ease of enforcing contracts and resolving insolvency.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

In Singapore, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) can arguably be said to be “appropriate dispute resolution” rather than “alternative dispute resolution”. ADR, by and large, does not take place in the shadow of the law; in fact, it very much operates under the aegis of the law. In Singapore, there is the recognition that access to justice can also take place outside the courtroom, primarily through ADR. Increasingly, disputants are encouraged and facilitated to look beyond the traditional court-based approaches to resolve their disputes. As discussed above (on civil procedure), ADR is integrated into the litigation process in the courts. In other words, litigation is promoted as a last resort.

The ADR movement started tentatively in the mid-1980s when the government envisaged Singapore as a major dispute resolution centre capitalising on its strategic geographic position as well as its goal of becoming a one-stop business centre. In the throes of the severe economic recession of 1985, the Economic Review Committee recommended the establishment of an arbitration centre in Singapore as part of a comprehensive package to make Singapore’s economy competitive. In August 1986, Singapore acceded to the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards in which each contracting State is required to recognise and enforce arbitral awards made in another contracting State.

In May 1996, the government created the Inter-Agency Committee on Alternative Dispute Resolution to examine how ADR processes, and in particular mediation, could be promoted in Singapore. In its July 1997 report, the Committee recommended, inter alia, that in order to prevent Singaporeans from becoming too litigious, less expensive and non-adversarial methods of dispute resolution should be encouraged for all forms of commercial, social and community disputes.

The goal of offering a full suite of ADR services while creating a Singapore brand of ADR was reiterated in the government’s major economic review in 2002-2003. This review reiterated the importance of the legal profession contributing to Singapore’s aspirations to be a business and services hub. In particular, it recommended that Singapore should aim to be an “important dispute resolution centre for the region”.[21] In August 2006, the government appointed Justice V K Rajah to head the Committee to Review the Legal Services Sector “to ensure that Singapore remains at the cutting edge as an international provider of legal services”.[22] To bolster its claim as a neutral, impartial, and effective ADR centre, Singapore leverages significantly on its corruption-free and efficient reputation.

A very recent example of the dynamic approach to ADR, sensitive to the realities of the day, is the SGUnited Mediation Initiative. In light of the economic and commercial hardships brought about by the COVID-19 global pandemic, the Supreme Court, in collaboration with the Singapore Mediation Centre (SMC), launched the SGUnited Mediation Initiative to help litigants resolve their disputes quickly and avoid protracted litigation. Under this initiative, the Supreme Court identifies cases suitable for mediation and then refers them to the SMC for mediation at no charge to parties.[23] This took place in July and August 2020. By facilitating mediated settlements through this initiative, the Supreme Court hopes to provide access to additional avenues for parties to resolve their disputes.[24] When mutually acceptable outcomes are achieved from a successful mediation, parties can save costs as well as minimise the emotional toll that accompanies the litigation.

3.3.1. Compulsory diversion of disputes to dispute resolution mechanisms

In Singapore, the compulsory diversion of disputes to dispute resolution mechanisms occurs within and outside the formal judicial machinery. To encourage the use of ADR, most of these mechanisms are government-financed or otherwise a formal part of the government structure.

3.3.2. Compulsory ADR: Presumption of ADR in the State Courts

Paragraph 35(9) of the State Courts Practice Directions provides that a presumption of ADR is applied to all civil cases.[25] For this purpose, the State Courts encourage parties to consider the Court Dispute Resolution (CDR) or ADR processes as a “first stop” for resolving the dispute, at the earliest possible stage and will, as a matter of course, refer appropriate matters to the CDR process or other ADR processes.

The judge-driven CDR process, which is a pre-trial case management process which employs specific CDR modalities such as Early Neutral Evaluation (ENE), judicial mediation and judge-direction negotiations, is overseen by the State Courts Centre for Dispute Resolution Cluster of the State Courts (CDRC). The CDR gives the parties the opportunity to resolve their disputes more expeditiously and economically compared to determination through the trial process. Neutral evaluation, mediation and conciliation and neutral evaluation are undertaken as part of the CDR process. The CDRC conducts CDR hearings which are pre-trial conferences convened under Order 34A of the Rules of Court.[26]

Aside from the CDR process, the State Courts encourage parties to consider using other ADR processes, including mediation at the Singapore Mediation Centre or Singapore International Mediation Centre, mediation under the Law Society Mediation Scheme, and/or arbitration under the Law Society Arbitration Scheme, and mediation and/or arbitration by private service providers.

A personal injury claim or a “non-injury motor accident claim” filed in the State Courts will be automatically managed by the CDR process. In such a claim, where parties are represented by counsel, the CDRC will give an ENE the case on liability and/or quantum to encourage parties to settle. As mentioned above, the Court may refer a Magistrate’s Court action for CDR or ADR at the CMC. To facilitate the Court’s decision on the most appropriate CDR or ADR process for the case, parties and their counsel must read and complete the CDR/ADR Form prior to the case management conference.[27] For any other civil case in the State Courts, parties may request for ADR at any time in the proceedings. A judge in the State Courts hearing a civil matter may also refer the case for ADR at any stage of proceedings. In particular, the parties and their solicitors must complete and file the CDR/ADR form when taking out or responding to a Summons for Directions application[28] or prior to the first Pre-Trial Conference (if no Summons for Directions or application for summary judgment, striking out, stay, transfer or consolidation of proceedings has been taken out for the case) to facilitate such referral.[29]

Several pre-action protocols are also in place for specific types of cases that would require pre-action steps to be taken prior to filing of a claim in court (and which steps include exchanging of proposals as part of pre-action negotiations). The specific types of cases are matters involving (1) Non-injury motor accident claims, (2) Medical negligence claims (3) Personal injury claims, (4) defamation, and (5) Business-to-Business debt claims.[30] The respective forms and pre-requisite steps to be taken as part of pre-action negotiations are set out in the protocol documents.

Prior to October 2018, the State Courts used two main dispute resolution techniques as part of its case management strategy, namely, mediation and neutral evaluation. Since then, the State Courts have begun using conciliation as a new court dispute resolution tool. The judge’s role during conciliation is to direct the parties through the negotiation process, and to suggest optimal solutions for their consideration. During conciliation, the judge plays a more active role than in mediation, where the mediator’s role is primarily to assist the parties in identifying key interests and to guide them to formulate their own solutions.[31]

Following the recommendation of the Inter-Agency Committee on ADR, the Community Mediation Centres Act (Cap 49A, 1998 Revised Edition) was enacted in 1997 to spearhead this endeavour. The Community Mediation Centre (CMC) promotes mediation as an effective means of addressing disputes regardless of whether users have been referred voluntarily. Although members of the public can bring their social disputes to the CMC, community mediation remains largely dependent on referrals by the authorities. Cases are often referred to the CMC by the Magistrates’ Court (without the need for consent of all the parties), the police, or other strategic partners like the Housing and Development Board (HDB).[32] The norms of mediation apply to community mediation. Parties are not required to produce evidence when undergoing mediation at the CMC. Access to the CMC is very affordable. Volunteer mediators are assigned to each case and legal representation is not allowed. When the disputants come to an agreement, a legally binding settlement is signed.

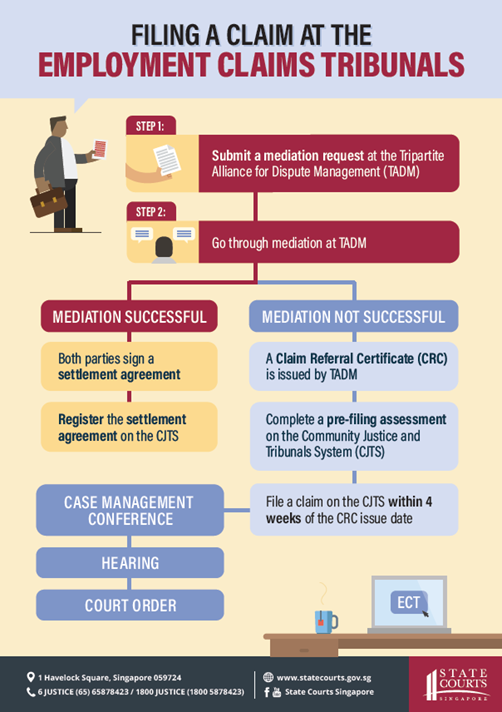

Other specialised dispute resolution forums include the Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents (under the Maintenance of Parents Act (Cap. 167B, 1996 Revised Edition), and the complaints process for the Commissioner for Labour to resolve salary disputes. These fora have been established to serve the needs of different groups, particularly those in need. Their simplified procedures allow cases to be heard expeditiously, at much lower cost, and without the need for representation by lawyers.

3.3.3. Voluntary or consensual diversion of disputes

A. Voluntary or Consensual ADR in the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court Practice Directions set out the requirement that solicitors must advise their clients on the various methods of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) available to resolve a dispute.[33] The methods described in the practice directions are mediation, neutral evaluation, expert determination, and conciliation.[34] The intent is for ADR to be considered at the earliest possible stage to facilitate the just, expeditious and economical disposal of civil cases. This is especially where ADR may save costs, achieve a quicker resolution, and a surer way of meeting the litigants’ needs.

Voluntary – Where ADR is sought by the initiative of one party: The Supreme Court Practice Directions provide[35] that a party may make an offer, in the prescribed form[36], for the dispute to be referred to ADR. The offer may be made at any time during proceedings and the opposing party must formally respond within 14 days.[37] If the opposing party fails to respond, that party will be deemed to be unwilling to attempt ADR without reason. This is a factor that the court may consider in exercising its discretion in an award as to costs, including costs of any claim or issue in any proceedings or of the entire action[38].

Consensual – Where ADR is sought by mutual agreement: If parties are willing to attempt ADR, directions may be given by the court in relation to the relevant civil case, including an adjournment of pending proceedings in court with stipulated timelines for the completion of the ADR process.[39] Where mediation is conducted under the SMC or SIMC, the Mediation Act 2017 provides for the mediated settlements to be enforceable in the Singapore Courts.[40]

3.3.4. Policy drivers in development of ADR processes

At a basic level, Singapore’s ideational approach to dispute resolution is to emplace a system in which the courts can expeditiously provide resolution for parties who seek out the legal system to resolve their disputes. That the courtroom should be the ultimum remedium (the forum of last resort) is a principle studiously subscribed to. To limit litigation’s reach, the state has sought to establish adequate facilities and incentives for ADR and make them accessible as the first port-of-call when parties seek to resolve their disputes.