National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

Canada is a federation consisting of ten provinces and three territories extending across the top of North America from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean. Canada’s southern border with the United States, stretching to almost 9000 Kilometres, is the world’s longest bi-national land border.

1.1. Form of Government

Canada is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy in the Westminster tradition, with a monarch and a prime minister who serves as the chair of the Cabinet and head of government. Each of Canada’s ten provinces and three territories has a similar governmental structure. The country is a realm within the Commonwealth of Nations and a member of the Francophonie. Canada is a member of several major international and intergovernmental institutions or groupings including the United Nations, NATO, OECD, the G7, the Group of Ten, the G20, and many regional (CUSMA, CPTPP, CETA) and bilateral free trade agreements.

1.2. Demographics, Ethnic Groups, Languages and Religions

Canada is the world’s second-largest country by total area but as a whole is sparsely populated by 37.59 million people. The majority of its land area is dominated by forest and tundra. Its population is highly urbanized, with over 80% of its inhabitants concentrated in large and medium-sized cities, and 70% residing within 100 kilometres of the southern border.

Canadian society is highly diverse. Indigenous peoples have inhabited what is now Canada for thousands of years before European colonization. Beginning in the 16th century, British and French expeditions explored and later began settling on this land giving Canada its bilingual (English and French) and bi-juridical (civil law and common law) foundation. At the federal level all government services and federally-regulated companies must make their public services available in both official languages. Canada has begun to acknowledge and make amends for its colonialism through constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights, truth and reconciliation initiatives, the fostering of various forms of Indigenous self-government, adoption of some Indigenous legal practices, and broader decolonialization efforts. Much work remains to be done on this front.

Canada is also a highly multicultural society, the product of large-scale immigration over several centuries, and is home to people from many countries representing a vast array of linguistic, ethnic and religious groups. There is no official religion.

1.3. Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

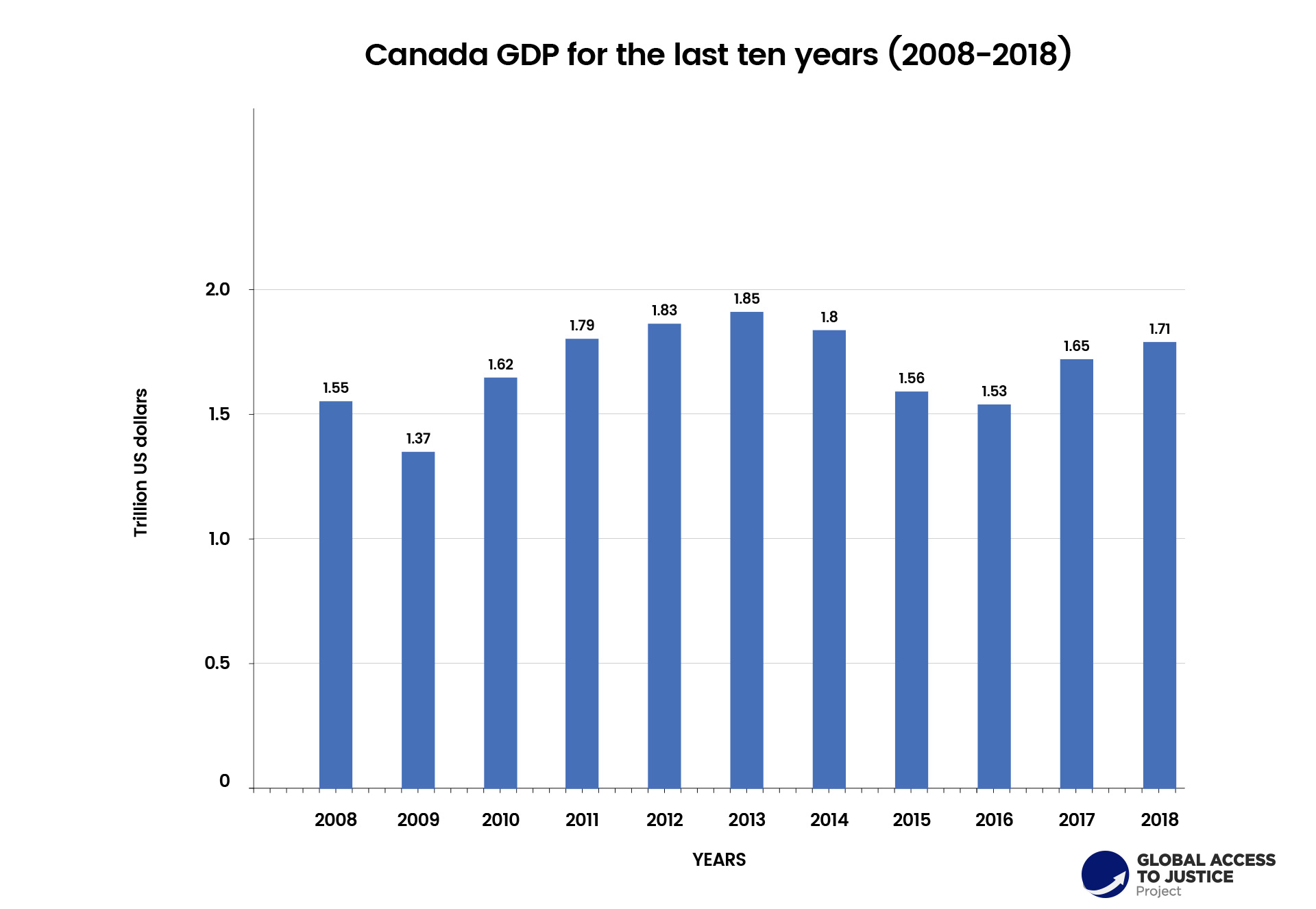

The economy of Canada is a highly developed market economy. It is the 10th largest economy by nominal and 16th by purchasing power parity. The IMF reports Canada’s GDP in trillion US dollars for the last ten years.[1]

Chart 01. Canada GDP for the last ten years (2008-2018)

1.4. Human Development Indicators

According to the UN Human Rights Development Index, Canada is rated as having very high development and is ranked 12th in the world in 2018.[2]

Chart 02. Human Development Indicators

| Human Development Index 2017 | Human Development Index 2016 | Life Expectancy at Birth |

Expected Years of Schooling |

Mean Years of Schooling | Gross National Income per Capita |

| 12th – 0.926 | 12th | 82.5 | 16.4 | 13.3 | $43,433 |

1.5. Canadians Living in Poverty

The most recent national statistics report that in 2017, 9.5% of the population lived below the official poverty line (down from 10.6% in 2016 and 12.1% in 2015).

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Hybrid Legal System

The Canadian justice system is unique in the world. Two official languages (English and French) and two legal traditions (common law and civil law) co-exist within our system of justice. As a legacy of the colonization of North America by France and Great Britain, two legal traditions are in effect in Canada – civil law in Québec and common law in all other provinces and territories. The co-existence of these two systems has important implications for federal lawmaking and statutory interpretation.

In addition, as part of the renewal of the relationship between Canadian governments and Indigenous peoples, initiatives are being taken to reflect Indigenous values within the justice system, to assist Indigenous people to assume greater responsibility for the administration of justice in their communities, and to decrease the rate of victimization, crime and incarceration among Indigenous people in communities through community-based justice programs.[1]

The Canadian constitution provides important parameters to the legal system by setting out the division of legislative powers between the federal and provincial/territorial levels of government and by enshrining the constitutional protection of rights and freedoms.[2] The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (“the Charter”) enacted in 1982 is a singular feature of the legal system giving the courts the responsibility to review legislation, regulations and other governmental actions for their consistency with the constitutional protections contained therein.[3]

Canada is a secular society and as a matter of law and policy religion is considered to be a private matter. The Charter provides constitutional protection to the freedom of conscience and religion (ss. 2(a)), among other rights and freedoms and further protections are provided by federal, provincial and territorial human rights legislation. Religious law is not enforceable in the Canadian legal system. For a short period of time the province of Ontario provided for the use of religious law in the arbitration of family law matters where both parties consented but this law was repealed. At present, nothing in Ontario law (or other Canadian jurisdictions) prevents people from turning to a religious official or someone knowledgeable in the principles of their religion to help them resolve their family dispute. However, if that person made a decision based on religious principles, the decision would not be a valid family arbitration award under the law.[4]

2.2. Federal Justice System[5]

The Canadian constitution provides for shared federal and provincial/territorial responsibility for the justice system. Provincial governments are granted the general power for the administration of justice in each province. The federal government has responsibility for, among other areas, criminal law, marriage and divorce law, and for the establishment of courts of plenary jurisdiction.

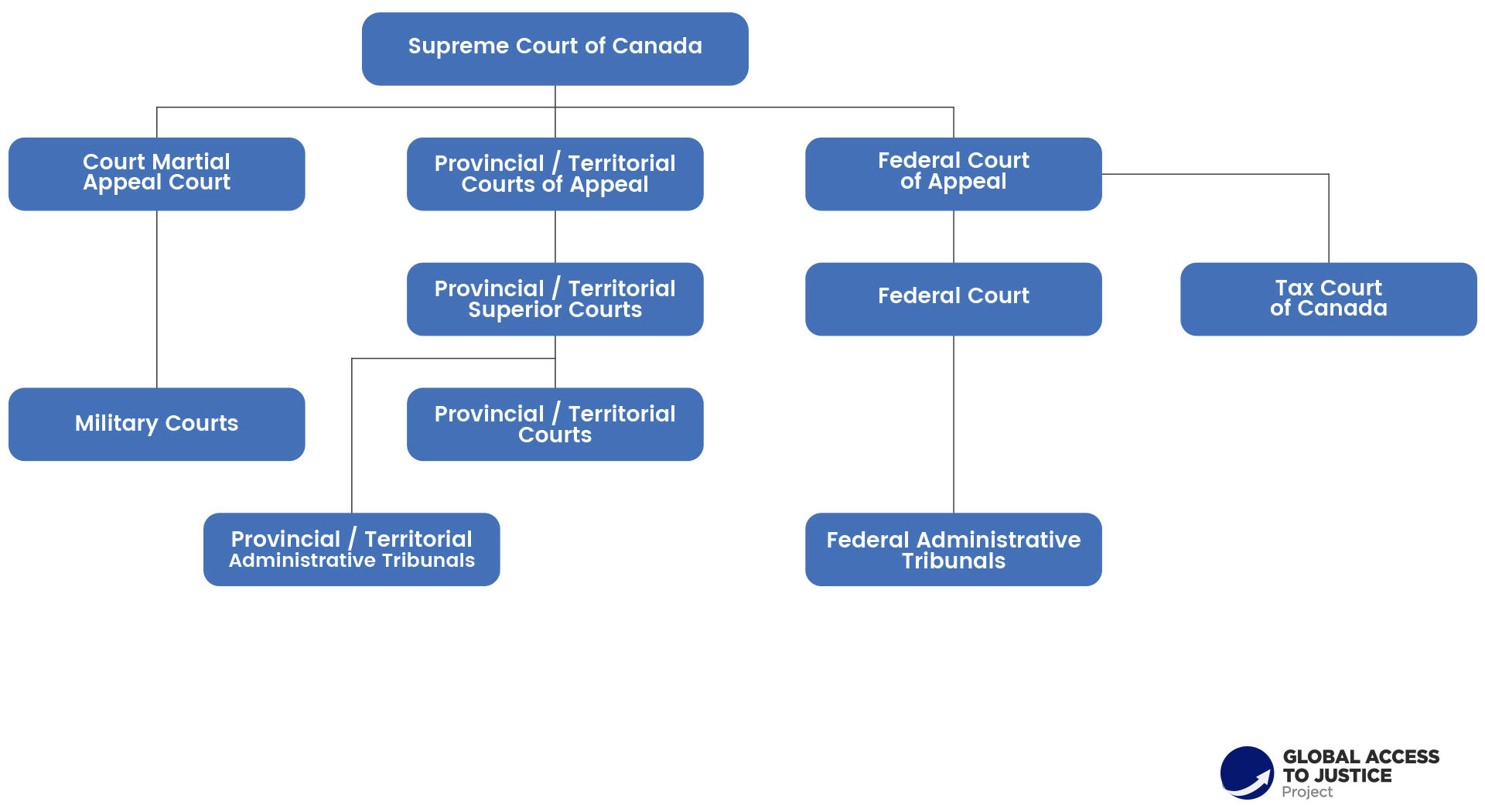

Canada has four levels of court and each type of court has its own jurisdiction, which means that it has the authority to decide specific types of cases.

- Provincial and territorial (lower) courts: These courts handle most cases that come into the system. They are established by provincial and territorial governments.

- Provincial and territorial superior courts: These are courts of plenary, or complete, jurisdiction established under section 96 of the Constitution Act, 1867. They deal with more serious crimes and civil matters and also hear many appeals from provincial and territorial courts. The Federal Court is on the same level, but is responsible for deciding civil matters assigned to it by statute, such as immigration and patents. The Federal Tax Court is also a federal superior court which deals with matters involving companies or individuals and tax issues with the Government of Canada

- Provincial and territorial courts of appeal and the Federal Court of Appeal.

- The Supreme Court of Canada, which is the final court of appeal for Canada.

2.3. Outline of Canada’s Court System[6]

Chart 03. Canada’s Court System

A. Provincial/Territorial Courts

Each province and territory has a provincial/territorial court, which hears cases involving either federal or provincial/territorial laws. In Nunavut, the Nunavut Court of Justice, which is Canada’s only single-level trial court, combines the power of the superior trial court and the territorial court so that the same judge can hear all cases that arise in the territory.

Provincial/territorial courts deal with:

- the majority of criminal offences, except the most serious ones;

- family law matters (e.g., child support, child protection, adoption, but not divorce);

- young persons from 12 to 17 years old in conflict with the law;

- traffic and bylaw violations;

- provincial/territorial regulatory offences;

- claims involving money, up to a certain amount (set by the province or territory);

- small claims in most jurisdictions (civil cases that resolve private disputes involving limited sums of money).

Some courts at this level are specialized, that is dedicated to particular types of offences or groups of offenders. One example is the Drug Treatment Court. The object of these courts is to address the needs of non-violent offenders who are charged with criminal offences that were motivated by their addiction. Those who qualify are offered judicial supervision and treatment for their addiction, with the help of community support services.

Youth courts handle cases for young people 12 to 17 years old who are charged with an offence under youth justice laws. Youth courts provide protections appropriate to the age of the accused, including protecting his or her privacy. Any court at either the provincial/territorial or superior court level can be designated a youth court.

All provinces and territories have established Domestic Violence Courts so that the justice system can improve its response to incidents of spousal abuse, provide better support to victims, and make offenders more accountable. These courts do this by:

- decreasing court processing time;

- increasing prosecution rates;

- providing a focal point for programs and services for victims and offenders; and

- allowing police, Crown prosecutors, and, in some cases, the judiciary to specialize in domestic violence matters.

The BC Provincial Courts have taken a leadership role in developing First Nations Courts in collaboration with local First Nations, the community at large, the Legal Services Society, Crown counsel, defence lawyers, Community Corrections, police, and groups like the Native Courtworker and Counselling Association of BC. Each court is designed to meet the unique needs of the community it serves. These courts do not conduct trials. They are sentencing courts that provide support and healing to assist in rehabilitation and to reduce recidivism while also acknowledging and repairing the harm done to victims and the community. Their focus is collaborative and holistic, recognizing the unique circumstances of Indigenous offenders within the framework of existing laws.[7] Other jurisdictions have developed similar initiatives.

B. Provincial/Territorial Superior Courts

Each province and territory has superior courts, which are courts of “inherent jurisdiction”. This means that they can hear cases in any area except when a statute or rule limits that authority. The superior courts try the most serious criminal and civil cases. These include divorce cases and cases that involve large amounts of money (the minimum is set by the province or territory in question). The jurisdiction of superior courts originally came from the first courts in England, whose authority over government actions was based on Magna Carta. Proceedings in superior courts are thus a continuation of a court process that dates back to the beginnings of the common law system.

The superior courts also act as a court of first appeal for the provincial and territorial courts that the provinces and territories maintain. Although the provinces and territories administer superior courts, the federal government appoints and pays the judges.

Although there are permanent court houses and judicial centres in all of Canada’s provinces and territories, Canada’s population is scattered widely across huge expanses of land, particularly in the North, and it may be difficult for individuals to travel to a court house to have their matter heard. In response, courts often travel “on circuit” to small or isolated areas.

C. Family Law Courts

In most provinces and territories, the superior court has special divisions, such as the family division. Some superior courts have established specialized family courts to deal with specific family law matters, including divorce and property claims.

Several provinces (Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan) use unified family courts. This allows a single court to deal with all aspects of family law, using specialized superior court judges and services. These courts encourage constructive, non-adversarial techniques to resolve issues, and provide access to support services through community organizations. These services typically include such programs as parent-education sessions, mediation, and counselling.

D. Provincial/Territorial Courts of Appeal

Each province and territory also has a court of appeal. These courts hear appeals from the decisions of the superior courts and the provincial/territorial courts. These can include a wide range of appeals, including commercial disputes, property disputes, negligence claims, family disputes, bankruptcies, and corporate reorganizations. Appeals are usually heard by a panel of three judges. The courts of appeal also hear constitutional questions that may be raised in appeals involving individuals, governments, or governmental agencies.

E. Administrative Tribunals

Administrative tribunals are independent, specialized governmental agencies established under federal or provincial legislation to implement legislative policy. Administrative tribunals in Canada make decisions on behalf of federal and provincial governments when it is impractical or inappropriate for the government to do so itself. Tribunals are set up by federal or provincial legislation, known as “empowering legislation”. Tribunals are commonly known as commissions or boards, and make decisions about a wide variety of issues, including disputes between people or between people and the government. Tribunals may also perform regulatory or licensing functions. Tribunal decisions may be reviewed by the courts. Because they engage in fact-finding and have the power to impact personal rights, tribunals are often seen as “quasi-judicial”.

Administrative tribunals perform a wide range of functions, including research and recommendation (e.g., law reform commissions), rule-making and policy development (e.g., the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission and provincial securities commissions), grant allocation (e.g., the Canada Council for the Arts and regional development agencies), adjudication (e.g., labour relations boards, landlord and tenant boards, immigration and refugee boards, municipal boards and human rights tribunals) and standard setting (e.g., environmental assessment boards, workers’ compensation boards and health and safety commissions). In addition to such permanent agencies, there are ad hoc administrative tribunals, such as arbitrators and inquiry commissions, mandated to deal with a specific subject matter.

Many administrative tribunals have a hearing process to determine conflicting rights and obligations or to assign rights or entitlements between competing parties. If a tribunal makes adjudicative decisions based on testimony and evidence, like a normal court, it will tend to function more like a court. Procedure is generally less formal than in court and the formal rules of evidence do not usually apply; however, decisions must be based only on cogent evidence. The decisions of administrative tribunals may be final and not subject to appeal, depending on the provisions and intent of the tribunal’s enabling legislation. Even where no right of appeal is provided or when a statute specifically forbids it, it is a principle of the Canadian Constitution that superior courts have jurisdiction to review any administrative tribunal’s function. This is called judicial review, and usually does not focus on whether the tribunal made the right decision, but whether it made the decision reasonably or correctly and within the scope of its empowering legislation.

For a further discussion of Canada’s system of justice, particularly in the context of promoting efficiency and access to justice, see further section 6.3 below.

2.4. The Structure of the Canadian Legal Profession

Every lawyer in Canada and notary in Québec is required by law to be a member of a law society and to be governed by its rules. Canada’s 14 provincial and territorial law societies govern over 125,000 lawyers, Québec’s 3,800 notaries and Ontario’s 10,500 independent paralegals in the public interest.[8] Each law society is established by provincial and territorial law and has a mandate to ensure that people in its jurisdiction are served by legal professionals who meet high standards of competence and professional conduct.

A central feature of Canada’s legal system is that the public has the right to obtain legal advice and be represented by a legal professional that is independent of the government. For that reason, Canada’s laws provide for the self-regulation of the legal profession.

For a further discussion of Canada’s legal profession, see section 8 below. One of the key strengths of Canada’s legal system is the clear distinction between the function of law societies and that of voluntary associations of members of the profession. The function of law societies is to regulate the legal profession in the public interest. It is the function of voluntary associations of members of the profession, such as the Canadian Bar Association, to speak for and represent the interests of their members.

To fulfill their public interest mandate, law societies set the standards for admission to the profession and the conduct of members in their province or territory. They audit and monitor the use of trust funds held by members of the profession. They also investigate complaints and discipline members of the profession who violate the required standards of conduct.

The provincial and territorial law societies coordinate their work on a national basis through the Federation of Law Societies of Canada (FLSC). As further discussed in section 8 below, the FLSC has undertaken national initiatives to break down barriers between the jurisdictions within Canada, including by breaking down barriers to mobility and facilitating the transfer of lawyers within Canada.[9]

There is no formal distinction between barristers and solicitors in Canada. At present, lawyers are subject to restrictions on how they structure their practices. Only licensed lawyers in sole practice or in firms owned and controlled by licensed legal professionals may provide legal services. These practices may only provide legal services and services that support or supplement legal services. These same restrictions apply to licensed paralegals in Ontario. Law societies currently permit lawyers to provide legal services through the following business structures: sole proprietorship, partnership, limited liability partnership, professional corporation, and multidisciplinary practice. Several law societies have investigated or are investigating the potential of alternative/expanded business structures.[10]

2.4.1. Number of Licensed Practicing Lawyers

According to statistics gathered by the FLSC, there were 104,497 practising lawyers (and notaries in Québec) in 2017, of which 47,155 were women.[11]

2.4.2. Affordability of Legal Fees[12]

Many studies have shown that Canadians do not or cannot access lawyers to assist them to resolve legal matters. The main reason given is affordability as there is a large gap between limited legal aid services available to low income individuals and those who can afford to pay full legal fees, particularly for litigation services. Law societies and bar associations have taken steps to address affordability issues through developments such as limited scope services[13] and advocating for greater availability of legal insurance.[14]

2.4.3. Legal Representation is Not Mandatory

Legal representation is not mandatory in Canada.

2.4.4. Representation by Paralegals

Traditionally, paralegals have not been allowed to provide legal representation services. More recently, some Canadian law societies have begun to expand the scope of practice of paralegals. In Ontario, where the law society licenses and regulates paralegals, they can offer legal services in defined areas such as small claims court, traffic court, tribunal work and certain criminal matters.[15] In British Columbia, for example, lawyers can supervise “designated paralegals” and delegate to them some representation services in tribunals or family law mediations.[16] In such cases, the supervising lawyer is responsible for the work carried out by the designated paralegal. Manitoba’s Law Society requested a change to the legislation to create new categories of service providers including technicians or paralegals, non-profits and limited licensees. Other jurisdictions have policies and initiatives with respect to paralegals.

2.4.5. Is There a Shortage of Lawyers in Canada?[17]

There is no consensus on the issue of whether there is a shortage of lawyers in Canada. The number of lawyers continues to increase, although statistics in the country’s most populous province, Ontario, show that the per capita number of lawyers in private practice is shrinking.[18] It is clear that many individuals do not access lawyers when attempting to resolve disputes for which a legal solution exists. Many Canadians rely on non-legal resources to address a range of legal problems and disputes. As noted above, affordability of legal fees, particularly for contentious matters is the main reported barrier.[19]

While overall there is no clear shortage of lawyers, geographic access to lawyers is uneven across Canada and individuals have experienced difficulty in some non-urban areas. Recent concerns about the geography of access to justice in Canada have focused on the dwindling number of lawyers in rural and remote areas, raising anxieties about the profession’s inability to meet current and future demands for localized legal services. These concerns have motivated a range of policy responses that aim to improve the education, training, recruitment and retention of practitioners in under-served areas.[20] These initiatives include opening two law schools at universities outside of main urban areas (at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia and Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario). Another example is the Rural Education and Access to Lawyers initiative, a joint initiative of the Law Foundation of BC, the Law Society of BC, and the Canadian Bar Association, BC Branch, which places law students in rural law firms for summer work experience and facilitates the placement of articled students in communities with less than 100,000 people and a greater than 500 person-to-lawyer ratio.[21]

2.4.6. Judicial Careers

Judicial independence is a cornerstone of the Canadian judicial system. That is why, under the Constitution, the judiciary is separate from and independent of the other two branches of government, the executive and legislature. Judicial independence guarantees that judges will be able to make decisions free of influence and based solely on fact and law.

The principle of judicial independence has three components: security of tenure, financial security, and administrative independence.[22]

Security of tenure: Once appointed, a judge is eligible to serve on the bench until retirement (age 75 for federally appointed judges, age 70 in some provincial/territorial jurisdictions). Judges can be removed by a joint address of Parliament or a provincial legislature, only after an independent and impartial investigation shows that there is good reason.

Financial security: Judges must be guaranteed sufficient compensation (including salary and pension) so they are not subject to pressure for financial considerations. In Canada, governments cannot change judges’ salaries or benefits without first receiving the recommendations of an independent compensation commission.

Administrative independence: No one can interfere with how courts manage the legal process and exercise their judicial functions. For example, only the chief justice can choose how cases are assigned to the judges of his or her court.

Several institutions have been established to support judicial independence: these include the Canadian Judicial Council, the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs, the National Judicial Institute and the Courts Administration Service. They help keep the government and the judiciary separate in areas like discipline, pay and benefits, and continuing education for judges.

Judges are appointed from the experienced members of the legal profession. The federal government appoints judges to the federal courts, the superior courts of the provinces/territories, and the Supreme Court of Canada. All federally appointed judges are appointed by the Governor in Council. This consists of the Governor General acting on the advice of the Prime Minister for judges of the Supreme Court of Canada and chief and associate chief justices in the provinces; and on the advice of the Minister of Justice for all other superior court judges.

Lawyers must apply for appointment through a fairly detailed application process. The Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs administers the advisory committees, representing each province and territory, which assess the qualifications of the lawyers who apply for federal judicial appointments. For example, a candidate for a federal appointment must have been a lawyer for at least ten years to be appointed and must be qualified to practise law in the jurisdiction in question. The provincial and territorial governments appoint judges to provincial and territorial courts. There are similar eligibility requirements for provincial and territorial appointments and a similar appointment process is followed.

Supernumerary judicial positions are also widely used in Canadian superior courts. A supernumerary judge is a judge who has the option to retire, but who instead chooses to sit half of the time of a full-time judge. Generally, when a judge becomes supernumerary a vacancy is created, and a new appointment is made to that Court. In Canada, a judge may request supernumerary status when they have continued in judicial office for at least 15 years and their combined age and number of years in judicial office is not less than 80 or they have attained the age of 70 years and have continued in judicial office for at least 10 years. Supernumerary judges account for almost 20 per cent of all active federally appointed judges.[23]

Chart 04. Number of Judges in Canadian Superior Courts[24]

A. Canada

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Efforts have been taken to make Canada’s system of judges more diverse, with more women, visible minorities, LBGT and Indigenous people on the bench.[26] Much work remains to be done however, and the number of Indigenous judges also remains low compared to other demographic groups. 2.4.8. Prosecutorial Careers Although the enactment of criminal law is under federal jurisdiction in Canada, the prosecution of most Criminal Code offences – outside of the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut – is the responsibility of the provincial Attorneys General and their lawful deputies by virtue of the administration of justice powers found in Section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 and the “interpretation” section of the Criminal Code. As a result, the vast majority of crown attorneys (also known as crown prosecutors or crown counsel in different provinces) are employed by Canada’s ten provinces. Crown counsel are public servants but operate independently of government and are not subject to election. They are represented by professional associations. Similarly, the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) is a national, independent and accountable prosecuting authority whose main objective is to prosecute federal offences and provides legal advice and assistance to law enforcement. The Canadian Association of Crown Counsel is the national association which represents the collective interests of Crown prosecutors and Crown lawyers. It contributes to helping governments and the public understand issues involving Crown prosecutors in the criminal justice system and Crown civil lawyers in the civil justice system. It addresses issues of Crown lawyers concerning conditions of employment and working conditions and promotes and encourages the professional development of Crown Counsels. Members include representatives of associations representing criminal and civil crown lawyers from the ten provinces and from the federal government.[27] There are no national statistics for the number of crown counsel but there are 460 in British Columbia, 850 in Ontario, 160 in Manitoba, and 90 in Nova Scotia. Many provinces have experienced a shortage of Crown attorneys, which has led to serious delays in the criminal justice process in some jurisdictions. For example, the Alberta Crown Attorney’s Association has reported that it is in a “state of continual crisis” due to “never-ending staff shortages, frozen wages, unpaid overtime and crushing workloads”.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1 Criminal Procedure

3.1.1. Criminal Investigations

Police are responsible for conducting criminal investigations. At the investigation stage, police gather and review information to figure out what happened. This may involve, for example, examining the place where the crime occurred and talking to victims and witnesses. Based on what they learn, police decide whether there is enough evidence to prove an accused committed a crime. If they think there is, they may make a report to Crown counsel recommending that charges be laid. Like Crown counsel all police activities, including investigations, must be done independently.

Here are the common steps in a police investigation:

- The investigation begins when a crime or an incident is reported/known to police.

- Police gather information from the victim, witnesses and other people involved.

- Police may ask the victim to complete a statement.

- Police may ask witnesses to complete a witness statement.

- In some situations, police may also examine the crime site to get any physical evidence. This may include forensic evidence.

- Police review the information collected and decide what action to take.

Canada is served by highly-trained police forces at the municipal, provincial and national levels and with specialized investigation branches in metropolitan areas as well as nationally as part of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

3.1.2. Criminal Prosecution Proceedings

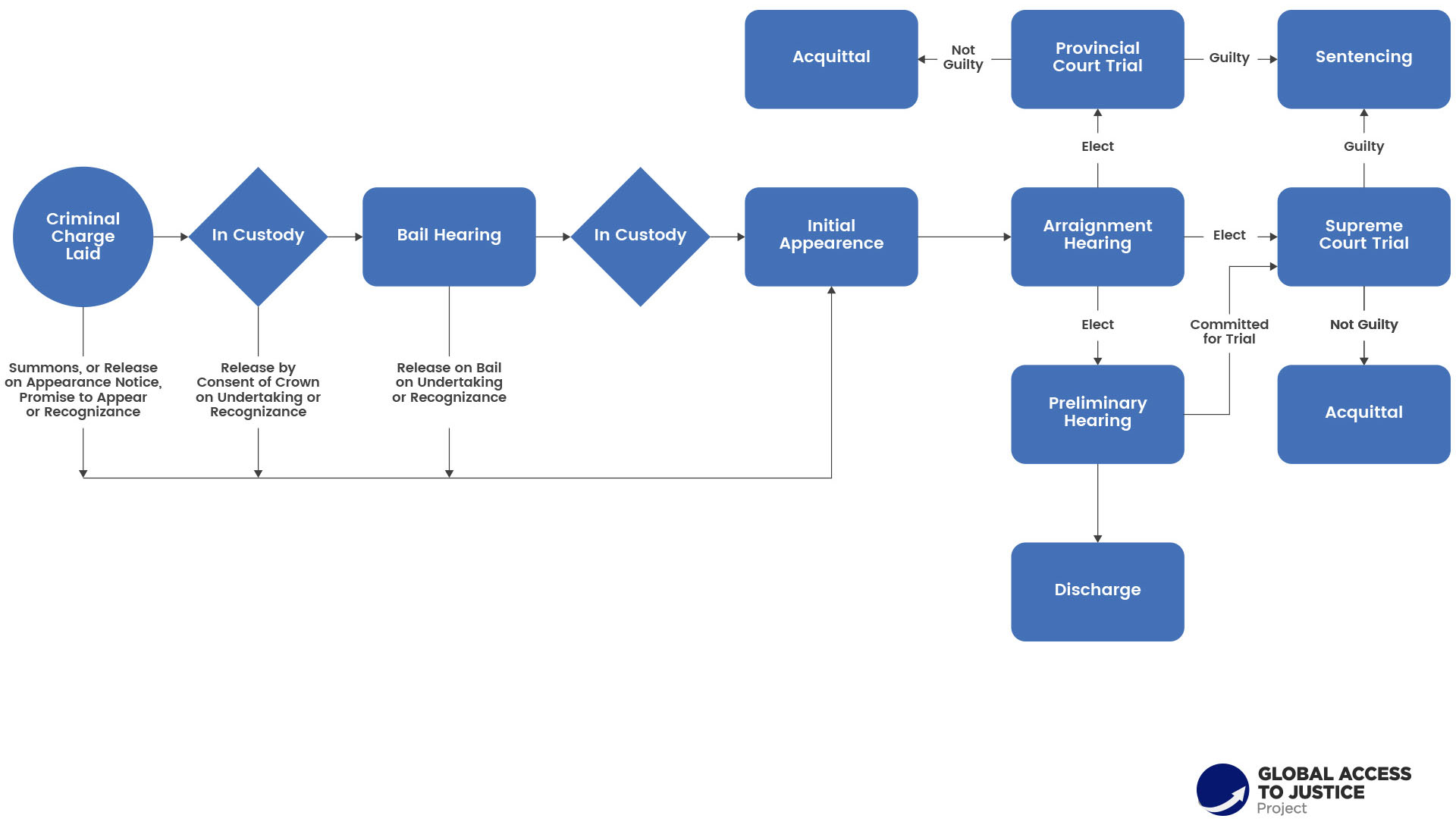

Criminal procedure is set out in federal legislation, the Canadian Criminal Code, and is therefore relatively consistent across the country. The British Columbia Provincial Court prepared the following criminal case flow chart, which provides a good basic overview of the criminal process in Canada.[1]

There are three types of offences (crimes): Summary Offences, Indictable Offences, and Dual or Hybrid Offences. Less serious crimes use what is known as the “summary conviction process”. The court process is simpler and the penalties are lower. More serious crimes proceed “by indictment”. Many crimes are “dual procedure” or “hybrid”, meaning the Crown chooses whether it will proceed summarily or by indictment. A jury is only available in very serious criminal matters.

3.1.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

The Canadian criminal justice system is generally compliant with the rule of law and due process. These rights are guaranteed under the Charter and accused persons have the right to plead violations of these rights in every case. Where these claims are successful, the accused has the right to an effective remedy (e.g. exclusion of evidence, mistrial). In addition, Charter claims often result in systemic changes in laws, policies and procedures since a finding of unconstitutionality must be fully remedied.

A longstanding concern has been the over-representation of Indigenous peoples both as victims of crime and within provincial and federal penitentiaries.[2] Canada has been subject to criticism by international treaty bodies for the “disproportionately high rate of incarceration of indigenous people, including women, in federal and provincial prisons across Canada”, as well as obstacles faced by Indigenous people in accessing justice.[3] The UN Human Rights Committee has urged Canada to “strengthen its efforts to promote and facilitate access to justice at all levels by indigenous peoples”.[4]

Another recurring concern is unreasonable delay in the criminal justice process. In 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada revisited this issue and rejected the framework traditionally used to determine whether an accused was tried within a reasonable time under section 11(b) of the Charter, replacing it with a presumptive ceiling of 18 months between the charges and the trial in a provincial court without preliminary inquiry, or 30 months in other cases.[5] Canadian governments, courts, crown prosecutors and other criminal justice system actors are taking active steps to reduce delays so that the criminal justice system can comply with this decision. Some examples of responses include improved case management techniques, court rule changes, and additional public investments.

In 2019, the Canadian government passed legislation enacting reforms aimed at making the criminal law and the criminal justice system clearer and more efficient, including by:

- streamlining bail processes to ensure fair and swift access to justice;

- creating a new process to more effectively and efficiently deal with certain administration of justice offences, including for youth;

- reclassifying offences to provide prosecutors with the discretion to more efficiently deal with less serious conduct, freeing up limited judicial resources;

- restricting the availability of preliminary inquiries to the offences carrying the most serious penalties to ensure criminal cases can proceed more efficiently to trial, and to reduce the impacts of testifying twice on victims;

- improving the jury selection process to make it more transparent and promote fairness and impartiality; and

- providing judges with more robust tools to manage the cases before them.[6]

3.2. Civil Procedure

3.2.1. Overview of Civil Procedures

Each Canadian court has adopted rules of civil procedure which set out the steps to be taken in a civil matter and many courts tailor litigation steps to different types of litigation (based, for example, on complexity of the matter). In general, these are the steps in a civil action:

- Bringing a claim

- The plaintiff prepares a statement of claim (e.g. notice of civil claim in BC), which contains a concise statement of material facts on which the plaintiff relies. The court issues the statement of claim.

- The plaintiff serves the statement of claim on all defendants and files an affidavit of service with the court.

- If the defendant does not defend the action, this affidavit of service is necessary for the plaintiff to obtain default judgment.

- Defending a claim

- The defendant prepares a statement of defence and serves it on the plaintiff, and files a copy with the court together with proof of service.

- The defendant may counterclaim against the plaintiff, cross-claim against a co-defendant, or make a third party claim against a non-party.

- Where a defendant fails to deliver a statement of defence within the prescribed time, the plaintiff may obtain default judgment from the court registrar or a judge, depending on the type of claim.

- Discovery

- Parties have an opportunity to obtain evidence required to pursue/defend the claim.

- In some courts, the parties must agree on a discovery plan if they wish to obtain evidence through the discovery process.

- The parties must deliver to all other parties an affidavit that lists all relevant documents in the party’s power, possession or control. Copies of the documents must be made available at a party’s request.

- A party may examine an opposing party, at which time the party must attend to answer questions under oath. The examination is recorded, and where requested, transcribed. Most courts have limits regarding which parties can be examined, how many examinations can take place and, in some cases, there is a maximum time limit.

- Setting an action down for trial

- Either party may set the action down for trial by serving and filing the trial record. A trial record includes a copy of all pleadings and orders relating to the trial.

- The registrar places the action on the trial list, or in some locations, trial dates are fixed by a judge in assignment court.

- Pre-trial conference

- In most courts, it is compulsory for parties to a pre-trial conference before a judge or court officer to attempt to settle the case or narrow the issues.

- Trial

- The plaintiff and defendant make opening statements. The plaintiff’s witnesses are examined and cross-examined. The defendant’s witnesses are examined and cross-examined. The plaintiff and defendant make closing arguments. In many cases, much of the evidence can be entered from the discovery process rather than through viva voce evidence.

- A judge may give judgment in court right after both sides have finished presenting their cases. Sometimes, however, the judge may not give the judgment right away but will give the decision later (this is called reserving judgment).

Over the years, courts have enacted rule changes aimed at simplifying civil procedures in order to increase access to justice by reducing complexity as a means to reduce cost and delay. One example is the increased use of summary judgment procedures. Another major step has been to consistently increase the jurisdiction of small claims courts by increasing the monetary value of the claims within their purview. British Columbia has established a Civil Resolution Tribunal, Canada’s first fully online tribunal, which now deals with motor vehicle injury disputes up to $50,000, small claims disputes up to $5,000, strata property (condominium) disputes of any amount, and societies and cooperative associations disputes of any amount (see further section 9 below).

3.2.2. Encouraging Settlement

The vast majority of Canadian civil cases do not proceed to trial. Most courts have taken steps to encourage the early resolution of disputes including:

- active case management;

- pre-trial settlement conferences presided over by judges or court officers (such as masters);

- the BC Civil Resolution Tribunal provides online assistance with negotiation between parties;

- also in British Columbia, mandatory private mediation that can be triggered by one of the parties delivering a notice of intention to mediate to the other side;

- in some courts, judicial dispute resolution (JDR) is available at various stages in the civil process;

- In the province of Québec, pursuant to legislation that came into effect on 1 January 2016, parties to an eventual litigation have the obligation to consider alternative dispute resolution methods before introducing a civil claim; and

- mediation is mandatory at the pre-trial stage in some Ontario courts.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

3.3.1. Compulsory and Voluntary ADR

Disputes are resolved by litigation unless the parties mutually agree upon an alternative method to resolve the dispute, which might include mediation, arbitration, or a combination of methods. However, even if a party commences litigation, that party may be required to attempt to resolve the dispute by way of ADR. The use of mediation is particularly widespread in family law matters.

Alternative dispute resolution processes, particularly mediation and arbitration, are widely used in Canada. For the most part, participation in these process is voluntary, often by prior agreement in a contract. Under statutory labour codes, arbitration is compulsory for many matters in the labour context. Most standard form commercial construction contracts include mediation as one of a few prerequisite steps to engaging in binding arbitration. Similarly, many consumer and employment agreements include mandatory arbitration clauses. The enforceability of these types of agreements is in some doubt following several recent court decisions.[7]

3.3.2. ADR Policy Drivers

The use of ADR in Canada is diffuse and diverse. In addition to civil procedure rules and encouragement from courts, codes of professional conduct also typically require that lawyers must consider ADR with their clients.

3.4. Simplification of Law and By-Passing Legal Processes

Proactive legal regimes such as consumer protection measures and regulatory oversight can contribute to access to justice by shifting the burden of enforcing legal rights and responsibilities and ensuring compliance to the regulator, rather than individual legal claims. Canada, however, has witnessed an opposite trend where administrative agencies, such as human rights and employment standards commissions originally intended to protect individuals through systemic enforcement and reliance, now rely almost exclusively on individuals to launch complaints.[8] This move away from state enforcement of standards has led to rising demand for related legal assistance, often undermining the original objective of preventing disputes and improving public protection.[9]

One successful example of by-passing court processes was the move to Workers Compensation schemes. Each province and territory in Canada has its own exclusive Workers’ Compensation Board/Commission, except the Northwest Territories and Nunavut have a combined Workers’ Compensation Board. There is substantial evidence that workers’ compensation systems deliver their benefits more efficiently than the tort system. Administrative costs consume 10% of workers’ compensation premiums in Ontario, compared to close to 50% for the tort system.[10] Workers’ compensation also handles many small claims that would not be brought under a tort system. Delays between injury and compensation are also much shorter under workers’ compensation than under tort law.[11] Canadian Workers’ Compensation Boards have also been proactive in workplace regulation to improve safety. For example, the BC Board (now WorkSafe BC) led the charge to prohibit smoking in the workplace.[12]

Court procedures are also by-passed to some extent through the adoption of no-fault automobile insurance under which policyholders are not only reimbursed by the policyholder’s own insurance company without proof of fault, but also restricted in the right to seek recovery through the civil-justice system for losses caused by other parties. Most provinces in Canada have some form of no-fault accident benefits that are paid to all collision victims. The difference is the degree to which tort (the right to sue) or no-fault (access to accident benefits) is emphasized. For example, Québec has a pure no-fault system that eliminates the right to sue, but provides substantial accident benefits. Ontario has a “hybrid” system, which blends no-fault and tort. Saskatchewan and Manitoba have either pure or hybrid no-fault insurance systems. British Columbia, Alberta and the Atlantic provinces have tort-based systems. In BC, recently introduced rules to simplify auto insurance claims were ruled unconstitutional.[13]

One highly successful example of simplification of law is the development of federal child support guidelines. The Federal guidelines are a set of rules and tables used to determine child support when parents get divorced.[14] They are the law. Their main goals are:

- to establish a fair standard of support for children so that they continue to benefit from both parents’ incomes after separation or divorce;

- to reduce conflict and tension between parents by making the calculation of child support more objective;

- to ensure that parents and children in similar situations are treated the same; and

- to make the legal process more efficient and encourage settlements by giving courts and parents guidance about child support.[15]

Whereas before support orders were litigated on a case-by-case basis, now, in almost all cases, judges are required to follow the guidelines to determine the amount of child support.[16] Many parents can use the child support guidelines to help them reach an agreement. If parents can agree, they have some flexibility in setting the child support amount, as long as reasonable arrangements have been made taking into account the guideline amount. The guidelines are coupled with family maintenance/support enforcement in each province and territory, which simplify the collection process.

An evaluation concluded: “Five years later, it is clear that the Guidelines are working well. Child support amounts are predictable and consistent, and the vast majority of parents are setting child support amounts without going to court.”[17] The Survey of Child Support Awards database confirms that the vast majority of cases involving child support under the Divorce Act are settled by consent: from 86 percent of all cases in 1997-98 to 88 percent in 1999 and 93 percent in 2000.[18] The Survey of Child Support Awards confirms that the Federal Child Support Guidelines have been used to determine child support orders in the vast majority of divorce cases in the selected courts. In addition, there seems to be little doubt that in the vast majority of cases the child support tables have gone a long way toward ensuring that children receive a fair amount of support and toward reducing conflict and tension between parents about child support. In 94 percent of sole custody cases processed under the Guidelines, the child support amount was greater than or equal to the table amount. The tables have also made the legal processing of cases more efficient and have helped ensure that parents and children in similar circumstances are treated consistently.

A similar approach was taken to the development of Spousal Support Guidelines, although these guidelines are advisory only and are not law. Nevertheless, judges often base their decisions about spousal support on the guidelines.[19] Many family lawyers also use the guidelines when helping clients to make decisions and set up spousal support agreements out of court.[20] Tools have been developed to help professionals use the guidelines.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

4.1. Rights to Access to Justice, Equal Access to Court and Fair Trial

Canada has a deep principled commitment to access to the courts and equal access to justice. The right to a fair trial in criminal matters is protected by sections 7-14 of the Canadian Charter and a broader right to a fair hearing and fair criminal trial by ss. 2(e) and (f) under the Canadian Bill of Rights, legislation adopted in 1960, which has quasi-constitutional status. A more general right of access to the superior courts has also been recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada in several cases.[1]

Canada is a signatory to all major international conventions including the many provisions concerning access to the courts. These international obligations are not directly enforceable by Canadian courts except to the extent that they have been specifically adopted in domestic legislation. International law does, however, play an important normative and interpretive role within the Canadian justice system.

4.2. Political Commitment to Access to Justice

Canada takes pride in having a strong, independent, and fair court system and effective rule of law. There is a strong political and societal consensus on these principles. At the same time, like in many countries, equal access to justice and the courts is not fully a reality in Canada, particularly with respect to non-criminal matters. Canadian governments, judiciary, law societies, bar associations and legal organizations have developed access to justice initiatives, though much work remains to be done.

Access to justice still is a relatively limited government priority and funding cuts often fall heavily on civil legal aid programs and other access to justice initiatives. This situation is reflected in the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index ranking of Canada, which is high on most indicators except access to civil justice, where Canada fares comparatively poorly relative to other developed countries.[2] Progress is also hindered by a lack of data measuring access to justice and, as a result, it is difficult to effectively evaluate how accessible justice is in Canada.[3]

Barriers to accessing justice are particularly onerous for persons of modest means and members of vulnerable and disadvantaged groups in Canada. This situation has been remarked upon by various international treaty bodies for over a decade now. Many of these conclusions are the direct result of cuts to funding to civil legal aid,[4] but others reflect the range of barriers faced by “aboriginal peoples, African Canadians and persons belonging to minority groups”,[5] women with disabilities,[6] and Indigenous women and members of minority groups.[7]

4.3. Canada’s Access to Justice Policy

There is no official national access to justice policy in Canada. Broad directions for reform were developed through a collaborative project involving key national justice organizations initiated, and currently chaired, by the former Chief Justice of Canada, the Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin: the National Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family Matters (Action Committee). The Action Committee developed a set of Justice Development Goals published in its 2013 report[8] and, with the assistance of the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice and others, has been reporting on progress toward their achievement.[9] A related companion report prepared by the Canadian Bar Association (CBA), Reaching Equal Justice (discussed further below), focuses to a greater extent on access to legal services as a key component of access to justice. Follow up to this work includes a joint project by the CBA and the Association of Legal Aid Plans proposing national benchmarks for public legal assistance services.[10] The CBA has also developed a series of modules, Legal Health Checks and Preventative Lawyering Toolkit, resources to help lawyers build the legal capabilities of their clients.[11]

Canada’s Justice Development Goals serve as a common framework to coordinate access to justice efforts, share innovations and measure progress. They are based on six guiding principles for change:

- Put the Public First

- Collaborate and Coordinate

- Prevent and Educate

- Simplify, Make Coherent, Proportional and Sustainable

- Take Action

- Focus on Outcomes[12]

The nine Justice Development Goals are:

A. Innovation Goals

1. Refocus the Justice System to Reflect and Address Everyday Legal Problem

2. Make Essential Legal Services Available to Everyone

3. Make Courts and Tribunals Fully Accessible Multi-Service Centres for Public Dispute Resolution

4. Make Coordinated and Appropriate Multidisciplinary Family Services Easily Accessible

B. Institutional and Structural Goals

5. Create Local and National Access to Justice Implementation Mechanisms

6. Promote a Sustainable, Accessible and Integrated Justice Agenda through Legal Education

7. Enhance the Innovation Capacity of the Civil and Family Justice System

C. Research and Funding Goals

8. Support Access to Justice Research to Promote Evidence-Based Policy Making

9. Promote Coherent, Integrated and Sustained Funding Strategies[13]

Further information about policies, practices and initiatives related to the achievement of the Justice Development Goals is available in the Action Committee reports available on the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice website.[14] These reports provide an annual update on access to justice initiatives across Canada, inclusive of a list of published research and evaluation reports. The Action Committee has also established a Metrics Working Group to address the Canada’s deficit in access to justice data.

4.4. Government Responsibility for Access to Justice Policy

In Canada, both the civil and criminal justice systems are fragmented by division of labour between organizations, a fragmentation that is reinforced by fundamental principles of an independent bench and bar. As a result, no one organization is responsible for ensuring access to justice. Some government departments of justice have established an office for this purpose, which is an important step forward, but these offices do not have effective decision-making power over the courts and lawyers. A major culture shift has occurred as a result of the Action Committee’s work: a collaborative group or committee has been established in each province or territory in the country. Each year, the Action Committee meets for its annual Summit bringing together representatives from these provincial/territorial collaborations and representatives of the justice sector institutions to coordinate access to justice efforts. As noted above, the Action Committee has also created vehicles to share access to justice ideas in Canada.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. The Legal Aid System in Canada[1]

5.1.1. A Brief History of Legal Aid

Canada has a national decentralized system of legal aid. The legal aid system is made up mainly of 13 provincial and territorial legal aid commissions or societies, legal aid “plans” as they are commonly referred to in Canada although the formal legal names are societies or commissions. Legal aid is considered to be an aspect of the administration of justice, which is a provincial responsibility under the division of powers set out in Sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act. There is one statutory legal aid plan in each province and territory, delivering criminal, family and non-family civil legal aid. There are other independent legal aid service providers that provide specialized services in areas such as disability or environmental law.

The national system of legal aid began to evolve in 1971. In that year the federal government entered into an agreement with the provinces to share the cost of providing criminal legal aid administered by the Department of Justice. As mentioned earlier, criminal law and procedure are federal powers in Canada. Prior to 1971 the availability of legal aid was uneven across the country. In most provinces legal aid had been provided on a limited pro bono basis by the provincial law societies and by private law firms. Province-wide legal aid had existed in British Columbia since 1952. The Ontario Legal Aid Plan was established in 1967. Non-profit legal aid organizations had been created in Québec City in 1951 and in Montréal in 1956. The federal Department of National Health and Welfare (presently called Health Canada) funded student legal clinics in four provinces; Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan and British Columbia during the 1960s.

In 1981-82 the federal government began making contributions to the cost of civil legal aid under a program called the Canada Assistance Plan (CAP), administered by the Department of National Health and Welfare. CAP was a federal program to support health and social services programs in the provinces and territories that were not explicitly areas of federal jurisdiction. In 1985 the CAP regulations were changed to formally include civil legal aid as a service eligible for federal support under the program as an “item of special need”.

5.1.2. The Right to Legal Aid

There is no specific legal right to legal aid in Canada. Citizens and residents of Canada have a right to a fair trial under the Legal Rights provisions of the Charter (ss. 7, 8, 9, 10) and under s. 15 (1) of the Equality Rights provision of the Charter. These Charter rights form the basis for a right to legal representation to assure a fair trial. The right to counsel to assure a fair hearing had been part of the Canadian Bill of Rights (1960). However, it was considered by judges as more interpretive in nature than the provisions of the Charter.

There is a specific right to legal advice based upon arrest and detention under R v. Brydges [1990] 1 S.C.R. 417. This is known as Brydges duty counsel. The police are required to make all reasonable efforts to allow detained persons to obtain legal advice as soon as practical. Legal aid lawyers are available to provide advice by telephone on a 24-hour, 7 day-a-week basis.

In civil matters Canadians have a right to legal representation in matters of child apprehension. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the denial of legal representation for parents in circumstances where a child is being apprehended by the state is a denial of the guarantee of life, liberty, and security of the person, guaranteed by s. 7 of the Charter.[2]

5.1.3. Significant Reforms of the Legal Aid System

On a national level the structure or legal aid is much as it was by the early 1970s for criminal legal aid and by the mid-1980s for civil legal aid. By 1973-74 all jurisdictions had signed agreements with the federal government for cost-sharing of criminal legal aid. By 1986-87, eight provinces were making claims for civil legal aid expenditures under CAP.

There has been one major change in legal aid funding on a national level. In 1995 dedicated federal funding for civil legal aid in the provinces was discontinued. In response to severe budget pressures the federal government terminated the CAP, replacing it with a large block funding program called the Canada Health and Social Transfer, later changed to the Canada Social Transfer (CST). With the end of CAP dedicated federal funding for civil legal aid was discontinued. The CST remains a block transfer program with no reporting requirements for specific areas of expenditure such as legal aid. The funds that had been provided to provinces under CAP in the year it was terminated, approximately $85 million, remained in the CST.

Federal funding for legal aid goes to provincial and federal treasuries. Funding for legal aid operations is provided by the provincial and territorial governments because the legal aid plans are bodies created by provincial or territorial statute. The change in federal funding for civil legal aid did not disrupt the growth of legal aid in the longer term.

Probably the most fundamental change occurring in legal aid delivery is a shift toward holistic and integrated service delivery. The Action Committee recommended the adoption of an expansive and user-centered approach in access to justice discourse in Canada.[3] Melina Buckley has outlined how the rationale for robust public legal assistance in Canada is changing with a growing appreciation of the results of current legal needs research.[4] Buckley suggests focusing on the cost of unmet need, providing a range of services and service providers to meet a range of needs, building the diagnostic capacity to match services to client needs, circumstances and capabilities, developing referrals and interagency collaboration across sectors and the emergence of collaborative leadership across sectors.[5]

There have been major influences in the past that have influenced legal aid in ways that have changed legal aid delivery. Among them have been the reformed legal regime for dealing with young offenders that emphasized alternative measures and diversion,[6] the Gladue decision of the Supreme Court of Canada that instructed lower courts to consider the unique circumstances of Aboriginal offenders at sentencing,[7] and, more broadly, the revolution in family law that began during the 1990s and continued in the years following. These were important influences to which legal aid responded, each one characterized by elements that adumbrated the impact of the paradigm shift that began to occur as the results of legal problems research filtered down from the level of scientific research to the worlds of policy and program development. This shift provided a coherent empirically based theoretical framework for thinking about legal aid. Lack of mandate and resources have sometimes slowed the course of this change to some extent in Canadian legal aid plans. Delivery models also play a role. It is more difficult to bring about change in judicare systems than in staff lawyer clinic models. Part of the reason is that low hourly rates or block fees and a narrow range of services defined by tariffs limit what private bar lawyers would be able/willing to do under the best of circumstances. However, legal aid plans are becoming more people-centered[8] in the sense of providing holistic and integrated service. This appears to be becoming the conventional thinking in legal aid, becoming reflected in many aspects of intake, assessment of needs and service delivery.

5.1.4. Democratic Development and the Growth of Legal Aid

The promulgation of the Charter, discussed earlier, has been the historical landmark that has undoubtedly strengthened the justice system in Canada, mainly in criminal law. Legal aid has been a key aspect of making the Charter a reality. Providing legal aid became more complicated as the influence of the Charter grew through the accumulating body of case law. At the same time, as will be discussed in subsequent sections, legal aid in Canada has continued to grow.

5.1.5. The Importance of Legal Aid for Delivering Access to Justice

Legal aid occupies the vast majority of the terrain of access to justice in Canada. On a national basis all legal aid plans received a total of 662,349 applications for criminal legal aid in 2016-17. About 81% of applications for criminal legal aid were approved. About 75% of civil legal aid applications were approved. Legal aid plans provided 1,161,853 in-court duty counsel assists during the same year.

In 2016-17 there were 1,227,546 criminal charges. Service delivery levels of approximately 930,000 duty counsel assists in criminal courts across the country. Bearing in mind that only a portion of persons charged with criminal offences plead not guilty, thus proceeding to more advanced stages of the criminal justice process, there were 277,000 approved legal aid applications for criminal legal aid. This indicates a substantial level of service relative to expressed demand. However, it does not address the broader issues of unmet need.

5.2. The Legislative Framework for Legal Aid

See the earlier discussion set out in section 5.1.

5.2.1. The Constitutional Right to Legal Aid

See the earlier discussion set out in section 5.1.

5.2.2. The Right to Legal Aid is Set Out in Other Laws

None of the provincial or territorial legislation establishing legal aid plans include a right to legal aid services. The legal aid legislation in both British Columbia and Ontario included statutory provisions assuring the accessibility of legal aid for eligible persons prior to the early 1990s. These provisions were removed in both provinces allowing governments greater flexibility to reduce legal aid spending during periods when governments were applying constraints to overall spending.

5.2.3. The Right to Legal Aid and Judicial Decisions

Apart from the decisions noted above in Section 5.1, the courts have been reluctant to render decisions that place demands on provincial and territorial expenditures. Lower criminal courts will often stay proceeding if the judge feels that an unrepresented accused will not receive a fair trial. Judges will not allow accused persons to be tried on serious matters without legal representation.

5.3 Institutional Framework for Legal Aid

As discussed earlier, legal aid is a provincial responsibility under the division of powers specified in ss. 91 and 92 of the Constitution. There is separate enabling legislation that creates the same effect for the three territories. Legal aid commissions and societies are created by provincial and territorial statutes.

5.3.1. State Responsibility for Legal Aid

See the earlier discussion set out in section 5.1.

5.3.2. Organizational Description at the National Level

Legal aid plans in 9 provinces – British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland & Labrador and Yukon – are governed by single boards of directors. Nunavut has a territory-wide board of directors, which includes representation from three regional clinics, Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet and Cambridge Bay. Each of the three regional clinics has a separate board of directors. The legal aid plans in Prince Edward Island and the Northwest Territories are part of the provincial or territorial Department of Justice. Prince Edward Island Legal Aid is a division of the Department of Justice and Public Safety. It does not have a board of Directors.

All of the legal aid plans function independently on a day-to-day operational basis. However, all of the plans are established by provincial and territorial statute and the level of funding is set by the provincial or territorial government. Government officials negotiate with the federal government concerning funding for legal aid in criminal, immigration and refugee matters. Therefore, governments exercise the ultimate power of the purse over the extent of legal aid services and broad matters of legal aid policy.

The heads of the legal aid plans exercise the ordinary operational management duties of a chief executive officer.

Legal aid plans in Canada employ a reported 2,516 persons. This includes 1,145 staff lawyers (45%), 602 legal workers, including intake workers, paralegals, legal assistants and articling students (31%), and 769 administrative and management staff (24%).

Alternative dispute resolution services, discussed earlier, are included in the tariff structures of most legal aid plans. These may include conciliation, mediation and collaborative lawyering. The Legal Services Society of British Columbia has an on-line legal service component known as MYLAW. This includes an on-line dispute resolution component for parenting disputes.

5.3.3. Delivery Models

In 2016-2017 there were 17,112 lawyers providing legal aid in Canada. On a national basis 93% were private bar lawyers providing legal aid on the basis of certificates issued to successful applicants by legal aid plans. The remaining 7% were staff lawyers.

Only one legal aid plan, Newfoundland and Labrador, is a predominantly staff lawyer system. Out of a total of 98 lawyers, 71% were staff, with 29% private bar.

Three jurisdictions were balanced mixed systems. Out of 198 lawyers providing legal aid in Saskatchewan, 57% were private bar lawyers. In Prince Edward Island, 58% of 46 lawyers were private bar and in the Northwest Territories 57% of the total of 37 lawyers were private bar lawyers.

The legal aid plans in 8 jurisdictions were totally or predominantly private bar systems. 98% of 1,099 lawyers providing legal aid in British Columbia were private bar lawyers, 98% of 4,619 lawyers in Alberta were private bar lawyers, 96% of 7,509 legal aid lawyers in Ontario were private bar lawyers, 86% of 2,692 lawyers in Québec were private bar lawyers, 85% of 331 lawyers in Manitoba were private bar lawyers, 79% of 145 lawyers in New Brunswick were private bar lawyers, and 71% of lawyers providing legal aid in Nova Scotia were from the private bar. No data is available for Nunavut.

Four jurisdictions employ small numbers of paralegals; Newfoundland and Labrador, 4; Ontario, 9; Manitoba, 5; and British Columbia, 2.

5.3.4. Development Strategies

In view of the large differences in the size, geographical variations and available funds, different legal aid systems have adopted different approaches to legal aid delivery, to meeting demands for service, and adapting to changing demand.

5.3.5. Client Participation in Setting Priorities

The nature and extent of client participation in legal aid boards varies among the 13 jurisdictions in Canada. The Action Committee’s work, discussed above, has encouraged public participation in justice policy discussions.

5.3.6. Data on Public Support for Legal Aid

Since 2008, the Legal Services Society of British Columbia has conducted annual public opinion polls to determine the degree of public support for legal aid. The 2018 poll revealed a very high level of public support for legal aid: 93% of the public supported legal aid overall, 76% of the public agreed that legal aid should provide service to resolve matters related to legal issues, and 87% felt that legal aid is important for assuring fairness in the justice system.[9]

5.4. National Legal Aid Expenditures

5.4.1. Sources of Legal Aid Funding

Legal aid plans reported total revenues of $846,282,419 in 2016-17. The vast majority of funding comes from governments. The total federal government contribution was $137,998,506. This amount included $119,735,829 for criminal legal aid and $18,750,000 for immigration and refugee legal aid. Provincial and territorial governments contributed a total of $671,262,677. Funding from both levels of government equalled approximately 92% of all sources.

Other sources of revenue were client contributions, 2% ($14,2454,114); contributions from the legal profession and from Law Foundations, 0.07% ($5,580,517) and other sources, 5% ($44,956,724). In all, non-government sources of funding equalled about 8% of the total.

5.4.2. Legal Aid a Component of the Justice System Budget

Legal aid budgets are distinguishable from the budgets of other parts of the justice system.

5.4.3. How Legal Aid Budgets Are Set

Legal aid budgets are set by provincial and territorial governments in consultation with legal aid plans in the respective jurisdictions.

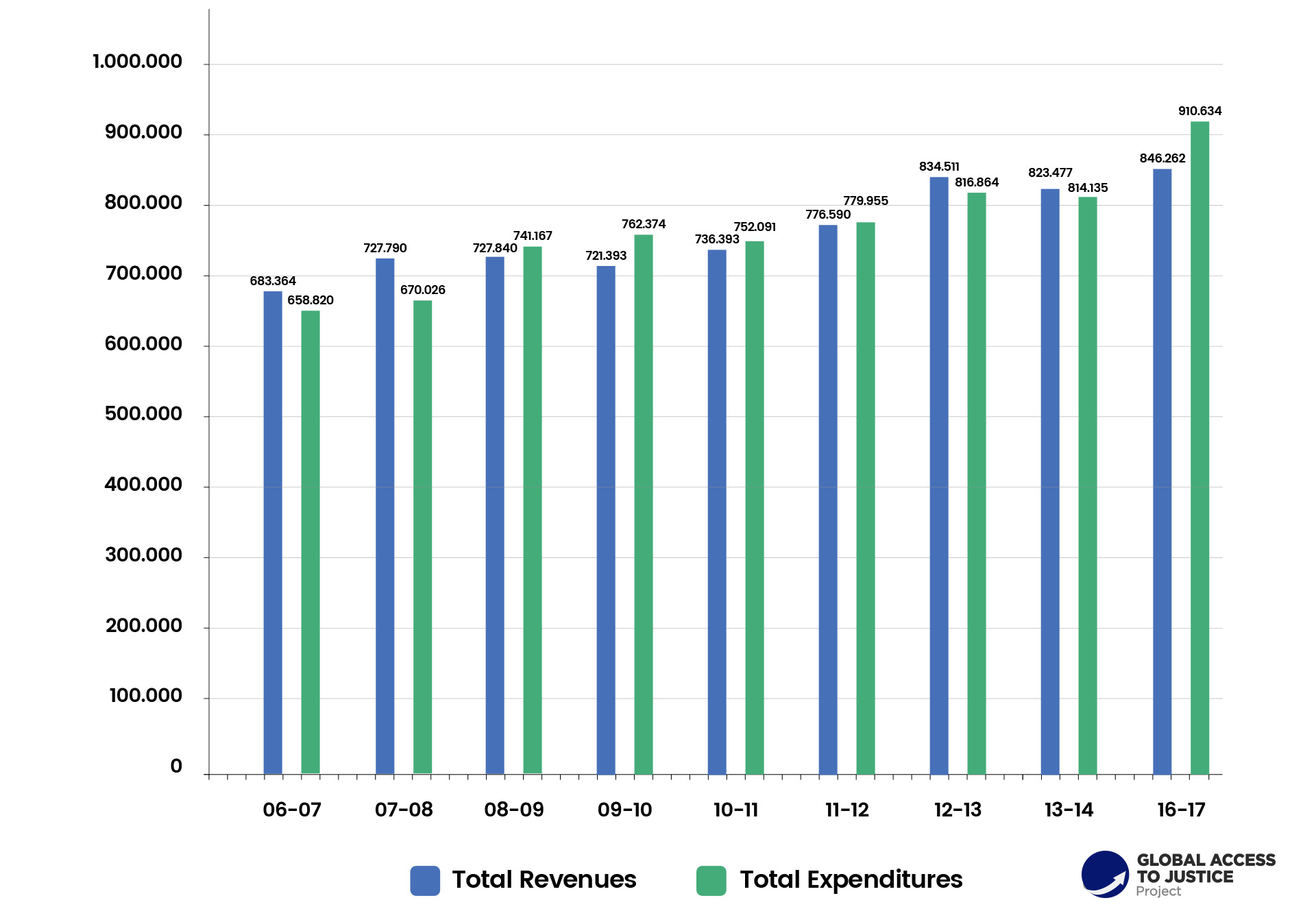

5.4.4. Total Legal Aid Revenues and Expenditures by Type of Service[10]

Chart 05. Total Legal Aid Revenues and Expenditures

5.4.5. Large Scale Budget Cuts

Historically, there have been two major budget cuts by legal aid plans. In Ontario, the provincial contribution to legal aid was reduced from $194.8 million in 1990-2000 to $171.1 million in 2001-2002. In British Columbia, the provincial contribution to legal aid was reduced from $83.8 million in 2001-2002 to $57.5 million in 2002-2003. The British Columbia cut resulted in the elimination of a major part of the legal aid delivery system, community clinics known as Community Legal Offices and Native Community Legal Offices. The federal government capped the contribution for criminal legal aid at the 1989-90 level.

Within the last 10 years the only major cut to legal aid occurred in Ontario in 2019 with a 35% ($133 million) reduction in the provincial contribution to legal aid.[11] The consequences, which are very significant, have not yet been fully realized.

5.5 Legal Providers

5.5.1. Qualifications for Legal Aid Lawyers

Lawyers must be members of the provincial or territorial Law Society in which they provide legal services (see the earlier discussion on the legal profession in Canada).

5.5.2. Procedure for the Hiring of Staff Lawyers

Legal aid plans recruit staff lawyers using normal competitive search and assessment methods.

5.5.3. Interest in Legal Aid Among the Private Bar

It has long been generalized, and sometimes over-generalized, that the commitment to legal aid among older and more well-established lawyers traditionally based on professional responsibility is diminishing. Younger lawyers often, although not always, use legal aid as an entry portal into the profession and then leave if and when they become sufficiently well-established. Much of the dissatisfaction with legal aid among the private bar focusses on the level of legal aid tariffs. Tariffs are generally felt to be half or less of the normal rate charged to non-legally aided clients. The phrase “low bono” has been used by lawyers to emphasize the fact that the private bar is subsidizing the government and the legal aid plans by providing services on the basis of low tariffs. Also, the limits on hours allowable under tariffs often adversely affects the ability of lawyers to provide effective representation to clients. This is said to effect family law service.

There are several factors that affect private bar participation in legal aid. In Canada, there are bilingual areas in which lawyers able to practise in both official languages are in high demand and less likely to participate in the legal aid system. In rural areas, the few practising attorneys may have ample business from paying clients and therefore may not always accept legally-aided clients.

Legal aid plans do not have difficulty recruiting staff lawyers, probably because, overall, the number of staff lawyers is relatively small. Staff lawyers are typically very committed to the legal aid work they do for their clients.

5.5.4. Payment of Legal Aid Lawyers

Private bar lawyers provide legal aid to individuals on the basis of legal aid certificates issued to accepted applicants by the legal aid plan. Lawyers are paid on the basis of a tariff of fees established by the legal aid plan. In general, tariffs are complex structures based on hourly rates with caps and block fees for different levels of offences and services. Tariffs differ from one plan to the next in terms of hourly rate and how caps and blocks are applied.

5.5.5. Level of Remuneration for Legal Aid Work

The fees paid to lawyers under the tariffs are reportedly about half or less of the rates charged by lawyers and reported in annual lawyer surveys.[12] Whether legal aid fees are adequate is partly a philosophical matter. When the national legal aid system was in its infancy, and lawyer attitudes were still strongly influenced by the pro bono era, objections to the low tariffs were not as strong. Providing legal aid to indigent clients was more likely to be considered as a professional responsibility. As legal aid became established as a government supported institution with budgets in the hundreds of millions of dollars, attitudes changed. The rationale for increased tariffs is nuanced and complicated, raising questions about the degree to which a system designed to provide assistance to the poor should support the income of the legal profession. In a predominantly private bar system, the legal profession is necessary for legal aid and there is an argument that the government should maintain the “health” of the legal profession for that reason. From another perspective, if an important objective of legal aid is to assure that the court system operates effectively, higher tariffs are easier to justify. However, to the extent that legal aid is viewed as a social program with objectives relating to alleviating social disadvantage and social exclusion, the argument for higher payments for lawyers takes on an added dimension. The five decades of the history of legal aid in Canada have shown that the tariff question does not have a simple answer.

5.5.6. Interference by Government in Legal Procedures

There is no evidence of direct interference by government in specific cases that legal aid normally provides service. However, controlling influence over types of cases for which service is provided can be exercised by government at a policy level through budget allocations. Government control can become more formal with memoranda of understanding that can direct legal aid plans with respect to which areas of law can be covered. This has been the case in British Columbia.

Provincial governments in British Columbia and Ontario have threatened to eliminate legal aid coverage for immigration and refugee matters. Although withdrawal of service has not actually occurred, the threat to do so was made by British Columbia in the early 2000s and recently in Ontario (2019). The basis for this is the assertion by provinces that immigration and refugee law and procedure is entirely under federal jurisdiction and therefore legal aid services to immigrants and refugee claimants should be 100% funded by the federal government. Since 2004-2005, the federal government has funded legal aid for immigrants and refugees in six provinces; Ontario, Québec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia.

5.5.7. Special Prerogatives and Privileges of Legal Aid Lawyers

Legal aid lawyers enjoy no special privileges in the justice system to enhance their work.

5.6. Quality Assurance

5.6.1. Minimum Standards for Legal Aid Lawyers

Any lawyer who is a member of the provincial or territorial bar can apply to the legal aid plan to be placed on the list of lawyers who can accept legal aid certificates.

5.6.2. Responsibility for Professional Standards

Provincial and territorial law societies are responsible for the professional conduct and quality of service of lawyers in the various jurisdictions.

5.6.3. Monitoring Quality of Service