National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

Belgium is a federal, representative democratic, constitutional monarchy. The King of the Belgians is the head of state, – the current King is Philippe – and the Prime Minister of Belgium is the head of government, in a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Federal legislative power is vested in both the government and the two chambers of parliament, the Senate and the Chamber of Representatives. The federation is made up of (language-based) communities and (territorial) regions.

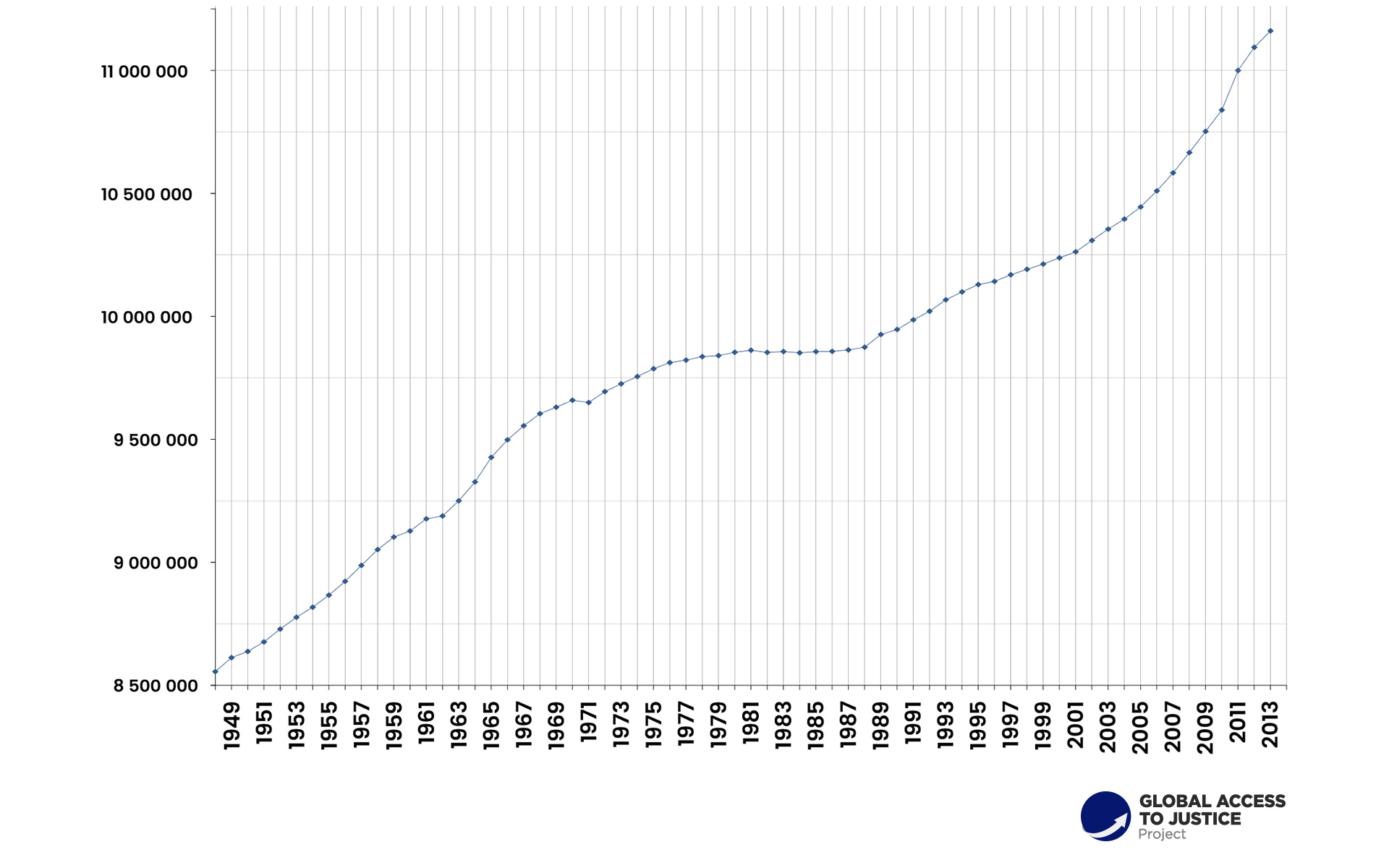

The Belgian population has grown after the second World War (see chart 01):

Chart 01. Belgian population.

Source: 1948-1959 United Nations Statistics Division and 1960-2009 Eurostat – Wikipedia

Source: 1948-1959 United Nations Statistics Division and 1960-2009 Eurostat – Wikipedia

As Wikipedia reveals:

Belgium had a population of 11,190,846 people on 1 January 2015 as compared to the 10,839,905 people on 1 January 2010, an increase of 601,000 in comparison to 2000 (10,239,085 inhabitants). The population of Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels on January 1, 2019 was 6,589,069 (57.6% of Belgium), 3,633,795 (31.8% of Belgium) and 1,208,542 (10.6% of Belgium), respectively. The population density of Belgium is 376/km2 (970/sq mi) as of November 1, 2019, making it the 22nd most densely populated country in the world, and the 6th most densely populated country in Europe.

The country is populated by a Flemish majority of about 6,400,000 people speaking Dutch, a French-speaking minority of 4,100,000 people (Walloons and French-speakers in Brussels), as well as 73,000 German speaking people in Wallonia, near the German border.

The largest group of immigrants and their descendants in Belgium are Italians, with more than 450,000 people, which is well over 4% of Belgium’s total population. The Moroccans are the third-largest group, and the largest Muslim ethnic group, numbering 220,000. The rest consists mostly of French-speaking people from Brussels, Turks, Kurds,[16] Dutch, French, Portuguese, Spaniards, Greeks, Bosniaks, Algerians, Congolese, Vietnamese, Poles, Indians, and Guineans (around 23% of Belgium’s population is of non-Belgian origin).

The exact number of French-speakers in Brussels is hard to determine, but it is estimated that 80% of the people living in Brussels use French and 20% use Dutch in their households, as the sole language or secondary language, while Arabic is also largely spoken.

In the table are the top 20 countries by origin of the population of Belgium in 2018:

Chart 02. Countries of origin of Belgian population (2018).

| Country | Number (2018) | % of foreign-born | % of total population |

| Morocco | 332,337 | 14% | 2.9% |

| Italy | 279,083 | 12% | 2.5% |

| France | 212,370 | 9% | 1.9% |

| Netherlands | 185,393 | 8% | 1.6% |

| Turkey | 159,759 | 7% | 1.4% |

| Romania | 100,245 | 4% | 0.9% |

| Poland | 95,904 | 4% | 0.8% |

| Spain | 74,872 | 3% | 0.7% |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 67,390 | 3% | 0.6% |

| Russia | 58,851 | 2% | 0.5% |

| Portugal | 52,334 | 2% | 0.5% |

| Germany | 50,563 | 2% | 0.4% |

| Bulgaria | 40,266 | 2% | 0.4% |

| Algeria | 30,921 | 1% | 0.3% |

| Syria | 30,299 | 1% | 0.3% |

| United Kingdom | 29,235 | 1% | 0.3% |

| Greece | 27,742 | 1% | 0.2% |

| India | 23,709 | 1% | 0.2% |

| Cameroon | 21,505 | 1% | 0.2% |

| China | 20,866 | 1% | 0.2% |

| Other countries | 529,323 | 22% | 4.7% |

| Total | 2,419,310 | 100% |

21.3%

|

Source: Wikipedia

Economically GDP and PPP are high and Belgium rates at the 17th place in the world. Life expectancy in Belgium is also high, due to a well elaborated welfare system. Gini-coefficient between 2010-17 is 27.7% and Belgium ranks at stage 17 in the world. And the expected years of schooling differs between female and male, but are rather high.

Chart 03. Life expectancy at birth from 2010-2018.

| Year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Life expectancy | 79,7 | 79,9 | 80,1 | 80,3 | 80,4 | 80,6 | 80,8 | 81 | 81,1 | 81,3 | 81,5 |

Source: UNDP

Chart 04. Expected years of schooling from 2010-2018: female and male.

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Female | 20 | 20,1 | 20,2 | 20,4 | 20,7 | 20,8 | 20,8 | 20,8 | 20,6 |

| Male | 18,1 | 18,2 | 18,3 | 18,4 | 18,7 | 18,8 | 18,8 | 18,8 | 18,8 |

Source: UNDP

Chart 05. PPP and GDP from 2008-2018.

| Year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| PPP | 42589 | 40410 | 42385 | 41700 | 42125 | 41688 | 41632 | 41598 | 42260 | 43300 | 43821 |

| GDP | 447,7 | 455,7 | 456,8 | 457,7 | 463,4 | 471,5 | 478,3 | 486,6 | 493,6 |

Source: UNDP

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of Legal System

Belgium is a federal state with a civil law system and is a member of the European Union.

The Belgian state was formed as a constitutional monarchy in 1830, as a compromise between French and Dutch claims, appeased by the British government. At that time its legal system was already largely influenced by the French legal system. The legislative branch was formed by a parliament with two chambers (Chamber and Senate). The King is the head of state and of the executive branch, but political power is almost entirely in the hands of the government and its prime minister.

Between 1970 and 1993, the country evolved into a more efficient federal structure. This occurred through six state reforms (in 1970, 1980, 1988-89, 1993, 2001 and 2011-2014). As a result, the first Article of the Belgian constitution reads today: ‘Belgium is a federal state, composed of communities and regions’. The redistribution of power occurred along two lines. The first line relates to language and, in a broader sense, to everything related to culture. The result was several communities. The concept of ‘community’ refers to persons that make up a community and the bond that unifies them, namely their language and culture. Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French and German. Correspondingly, Belgium today, has three communities: the Flemish Community, the French Community and the German-speaking Community. The second line of state reform was historically inspired by economic interests. The regions, which aspired to more economic autonomy, conveyed these interests. This lead to the establishment of the three regions: the Flemish Region, the Brussels Capital Region and the Walloon Region. Up to a certain level the communities and the regions can be compared with the American states or the German ‘Länder’.

The federal government issues acts (wet/loi), while the regions and communities issue decrees (decreet/decret). However, the core of the civil, commercial and criminal law still remains at the federal level, whereas mostly public law issues like education, environment and culture, have become the competence of the regions and communities. The organisation of the courts in Belgium is a solely federal responsibility.

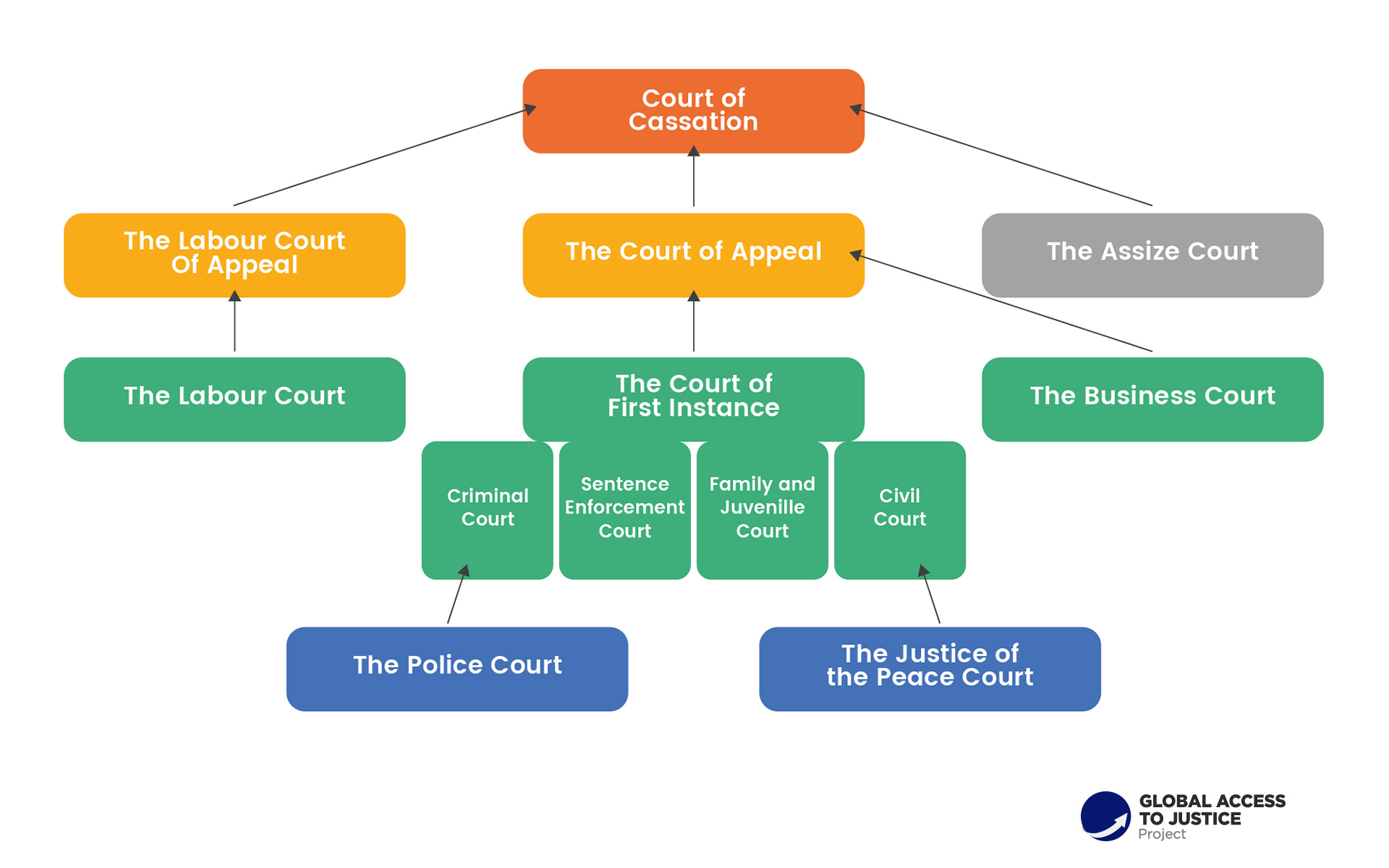

2.2. The Belgian Justice System

The Belgian judicial system is a system in the civil law tradition, in which a set of codified rules is applied and interpreted by judges. Being part of the European Union Belgium has to apply European legislation and has to give regard to rulings of the European Court of Justice. Belgium is also signatory to the European Convention of Human Rights and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights strongly influences the Belgian approach towards fundamental rights. The importance of this European dimension is evident and keeps growing.

Notwithstanding Belgium is a federal state it still has a unified/unitary national justice system with multiple levels of courts (for more details see: Taelman en Van Severen, 2018). The Belgian court system resembles the French system. The ordinary courts rank in four levels:

2.2.1. Inferior or local courts

The Police Court and the Justice of the Peace Court form the lowest levels of the Belgian court system.

The Justice of the Peace Court (justice de paix/vredegerecht) is a small claims court. It deals with all claims below € 5,000 that are not exclusively assigned to another court. The Justice of the Peace Court is also regarded as a proximity court with a specific jurisdiction over disputes regarding real estate (i.a. lease disputes), neighbour disputes and actions regarding guardianship. There are 162 Justice of the Peace Courts in Belgium (one for each judicial canton).

The Police Court (tribunal de police/politierechtbank) is a traffic court. The police Court has not only criminal jurisdiction regarding traffic offences, but it also has exclusive jurisdiction in civil matters for all compensatory claims relating to traffic accidents. There are 15 police courts in Belgium, i.e. one for each judicial district, except for Brussels where there are four.

2.2.2. Courts of First Instance

The normal starting level (first instance) is the Court of First Instance (tribunal de première instance/rechtbank van eerste aanleg). It deals with both civil and criminal matters. The Court of First Instance is divided into three or four sections. Each Court of First Instance has the following sections: (i) the Civil Court, (ii) The Family and Juvenile Court and (iii) the Criminal Court. Courts of First Instance located in the same city where a Court of Appeal is vested are comprised with a fourth section: the Sentence Enforcement Court. Specialized tax chambers were added to the formal organisation of the Courts of First Instance. There are 13 Courts of First Instance in Belgium (one for each judicial district and two in the Brussels district – one Dutch-speaking and one French-speaking).

Besides the Court of First Instance two specialised courts exist: the Business Court and the Labour Court. Both specialised courts have lay judges alongside professional magistrates. There are nine Business Courts and nine Labour Tribunals in Belgium. In principle, one in the territorial jurisdiction of each Court of Appeal, except for the territorial jurisdiction of the Brussels Court of Appeal, where there are courts in Leuven and Nivelles and two more in Brussels itself – one Dutch-speaking and one French-speaking – and except for the judicial district of Eupen, which has it own German-speaking courts.

The Business Court (tribunal de l’entreprise/ondernemingsrechtbank) has general jurisdiction with regard to all disputes between undertakings[1]. Insolvency proceedings (bankruptcy and business restructuring) belong to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Business Court.

The Labour Tribunal (tribunal du travail/arbeidsrechtbank) has specific jurisdiction regarding matters of individual labour law and social security law.

2.2.3. The Assize Court

The most serious criminal offenses appear before the Assize Court (cour d’assises/hof van assisen), the only Belgian court with a jury. There is a court of assizes for each of the 10 provinces and for the Brussels administrative district. It is not a permanent court but is convened whenever accused persons are sent before it.

2.2.4. Appeal courts

The appeal level is formed by the Courts of Appeal and the Labour Courts of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal (cour d’appel/hof van beroep) deals with appeals against decisions of the Court of First Instance and the Business Court, rendered in first instance. The Court of Appeal thus handles civil, criminal and commercial matters. There are five courts of appeal in Belgium.

The Labour Court of Appeal (cour du travail/arbeidshof) is the appellate court for social law cases coming from the lower Labour Tribunals. They have the same territorial jurisdiction as the Courts of Appeal.

2.2.5. Court of Cassation

The Court of Cassation (Cour de cassation/Hof van Cassatie) is the supreme court, which is located in Brussels. The Court of Cassation is the highest appeal level, dealing only with points of law, no new facts can be brought before this court.

Chart 06. The Belgian Justice System.

Source: UA

In Belgium parallel or informal justice structures are not widespread. Although not much research exists, religious leaders play within certain population groups an important role in the informal handling of disputes (e.g. the Jewish community in Belgium; see: J. Kusters 2008).

2.3. The Structure of the Legal Profession

Law degrees are primarily oriented towards the traditional legal professions: attorneys, notaries, bailiffs and magistrates. Non-traditional professions include government officials, corporate lawyers, and professions that may have no legal component (Van Houtte & Gibens 2001-02). Hereafter we discuss briefly the division of tasks between attorneys, bailiffs and notaries

2.3.1. Attorney

Core tasks of an attorney in Belgium are representing, assisting and defending the client in legal proceedings and providing legal advice[2].

According to the latest figures (2018), there are about 18,740 attorneys in Belgium. 10,800 lawyers are members of the Flemish Bar Association. The Association of the French-speaking and German-speaking Bars counts 7940 licensed members.

In 2019 the Association of the French-speaking and German-speaking Bars published the results of a survey to find out what hourly rates their lawyers charge. The average hourly rate amounts to €160.12 (excluding VAT), whereas it was 14% lower 10 years ago. For private clients the average was €126.66 (+ 24% compared to 10 years ago) and for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) a lawyer charges an average of €161.70 (+ 22%). Large companies pay an average of €181.11 (+18%). For Flanders, it is waiting for a new lawyer’s survey, but the figures could well be comparable.[3] By way of comparison, in 2016 the average net taxable income per inhabitant in Belgium was €17,824.

Besides a (normal economic) increase of the fees charged by the lawyers, also other factors led to a serious aggravation of the total financial burden of conducting legal proceedings: in order to encourage ADR the court fees were recently increased, a contribution to the Budget Fund for second-line legal aid was introduced and since 2014 attorneys have to charge VAT on their services, which led to a de facto increase in lawyers’ fees by 21% (Rutten, 2018).

Quite recently the Flemish Bar Association, in consultation with the Association of the French-speaking and German-speaking Bars, created the possibility for attorneys to create Multi-Disciplinary Practices within certain limits. A ‘multidisciplinary association’ (the multidisciplinary alliance to which the members have fully or partially transferred the exercise of their respective professions and have contractually set out how the profits or losses of the alliance, the control, or the ultimate responsibility will be divided among them[4]) remains forbidden.[5] A ‘Multidisciplinary grouping’ (the multidisciplinary alliance whose members have contractually only determined how they will organize common services to support the practice of the profession by its members and how the related costs will be shared[6]) and a ‘multidisciplinary network’ (the multidisciplinary alliance whose members practice their profession separately from each other but recommend other members of the network to their clients[7]) are allowed.[8] A lawyer and a notary could thus decide to create a multidisciplinary grouping together. Non-lawyer ownership and non-lawyer management of a law firm remain impossible.

2.3.2. Bailiff

Bailiffs are Ministerial Officers. A Ministerial Officer is a person appointed by the King (in practice by the Ministry of Justice) and entrusted with specific public service tasks. Nevertheless bailiffs are self-employed. Bailiffs have two key tasks. First of all bailiffs are in charge of the service of documents such as a writ of summons, a court ruling, a payment order, etc. Another primary task of the bailiff is the enforcement of court orders, authentic deeds and other enforceable titles. Enforcement means that the bailiff will seize movable property, bank accounts or real estate or will collect penalty payments for non-compliance with a court order (Article 1385bis of the Judicial Code). Aside from their court duties, established by Article 519, §1 of the Belgian Judicial Code, bailiffs also have a wide range of out-of-court activities which they can perform, including inter alia the amicable recovery of debts.

2.3.3. Notary

The profession of notary in Belgium is that of a typical civil law notary. The main activity of a civil law notary is drawing up authentic deeds. By authenticating agreements, the civil law notary gives them a special value that private contracts do not have: as an authentic form of evidence and as regards their enforceability. For some transactions an authentic deed is compulsory. When an authentic deed is not necessary, the civil law notary can assist his clients in drawing up a contract. The liquidation of a succession is another task traditionally entrusted to civil law notaries. The civil law notary is often consulted for drawing up the will. At the time of death, the civil law notary gets in touch with the heirs, provides the information relating to the acceptance or renunciation of the inheritance, proceeds with the division of the inheritance and attends to the procedures that are required to be fulfilled for tax purposes. Civil law notaries may provide consultations or opinions without necessarily having to draw up any deed or agreement.

2.3.4. Paralegal

‘University colleges’ (hogescholen in Dutch) offer a professional Bachelor’s degree in legal practice. People who obtained this degree are commonly referred to as ‘legal practitioners’; in an international context one might say that the Belgian term ‘legal practitioners’ corresponds more or less with the occupation of paralegal. Although paralegals do not have access to the classic professions, legal practitioners can find opportunities performing important preparatory legal and administrative work, including drafting official documents, providing information to applicants, and taking notes during court sessions. Legal practitioners find jobs in the private sector (30 per cent, primarily with banks and insurance companies, as well as in real estate and industry), government (18 per cent, primarily as clerks), and as employees of attorneys, notaries and bailiffs (20 per cent); 4 per cent are self-employed, and the rest work in diverse fields (Van Delm 2012).

2.4. Legal representation in Court

In Belgium self-representation is permissible in all courts, with the exception of the Court of Cassation. In order to conduct proceedings in front of the Court of Cassation, a party must be represented by a member of the Bar of the Court of Cassation (which has only 20 members). In criminal cases representation in front of the Court of Cassation is also possible by attorneys who are certified by the Bar, after having followed a specialised training. In tax cases any attorney can represent a client during supreme court proceedings.

If litigants do not opt for self-representation, they are in principle obliged to be represented by an attorney. In court the parties or their counsel must appear in person. In general, attorneys have a monopoly of representation in civil and in criminal cases and representation by accountants or paralegals is not permitted in Belgium. Legal entities are self-represented by their legally empowered representatives. Before the Justice of the Peace, the Business Court, and the Labour Court, the parties can be represented by a spouse, a legally cohabiting partner or by a family member as long as the representative holds a proxy and the court allows the representation (art. 728, §2 of the Judicial Code). In tax cases, the court can allow the parties to be assisted (not represented) by an accountant (art. 728, §2bis of the Judicial Code). Before the Labour Court, the parties have the right to be represented by a union representative (art. 728, §3 of the Judicial Code). In some social security disputes between an individual and a Public Centre for Social Welfare (PCSW), some particular rules apply (art. 728, §3 of the Judicial Code). The individual can be represented or assisted by a representative from a non-profit organisation, which takes care of the group of persons referred to in the relevant legislation. The PCSW can be represented by an attorney or a staff member.

2.5. Belgian Magistracy

Alongside the legislative power and the executive power, the Constitution established the judicial power, exercised by the law courts. The courts thus constitute an independent power alongside the other constitutional powers. The judicial power is exercised by the courts in accordance with the constitutional and legal provisions. The role of the judiciary is to judge cases. A distinction is made between the judges adjudicating cases in court (la magistrature assise/de zittende magistratuur, ‘sitting judges’) and the lawyers who work in the Public Prosecutor’s Office (PPO) (ministère public/openbaar ministerie,), who essentially bring prosecutions (la magistrature debout/de staande magistratuur, ‘standing judges’).

In Belgium, only an examination, organised by the High Council of Justice, provides entry to the judiciary. The examinations to become a judge or a public prosecutor are organised by the French-language Nominations and Appointments Committee (CND) and the Dutch-language Nominations and Appointments Committee (BAC) of the High Council of Justice.

The exams are intended to assess the maturity and aptitude needed for the performance of judicial duties. Not only the candidate’s intellectual abilities, but also other aptitudes, such as the candidate’s listening skills and tolerance to stress are assessed.

There are three ways of entering the judiciary: (1) the judicial traineeship, (2) the professional aptitude exam and (3) the oral evaluation exam.

The judicial internship entrance exam forms the access towards the judiciary for young lawyers who have at least two year’s professional experience in the legal sector. Via a (written and oral) entrance exam those lawyers qualify for a judicial internship of 24 months. After completing the judicial internship successfully, they can apply for a vacant position as a public prosecutor or a judge.

The second access to the judiciary is the professional aptitude examination. Candidates need at least four years of working experience. After successfully passing the professional aptitude exam they will obtain a certificate. This certificates enables the laureates of the exam to apply immediately for a position as a judge or a public prosecutor. The certificate is valid for seven years.

The third entry to the judiciary is the oral evaluation examination. This exam is reserved for candidates who have acquired many years of professional experience. The awarded certificate, giving instant access to a vacancy, is valid for three years.

Candidates who have successfully passed an examination and who, if applicable, have completed a judicial internship, do not automatically become judges, but can apply when there is a vacancy published in the Belgian Official Gazette.

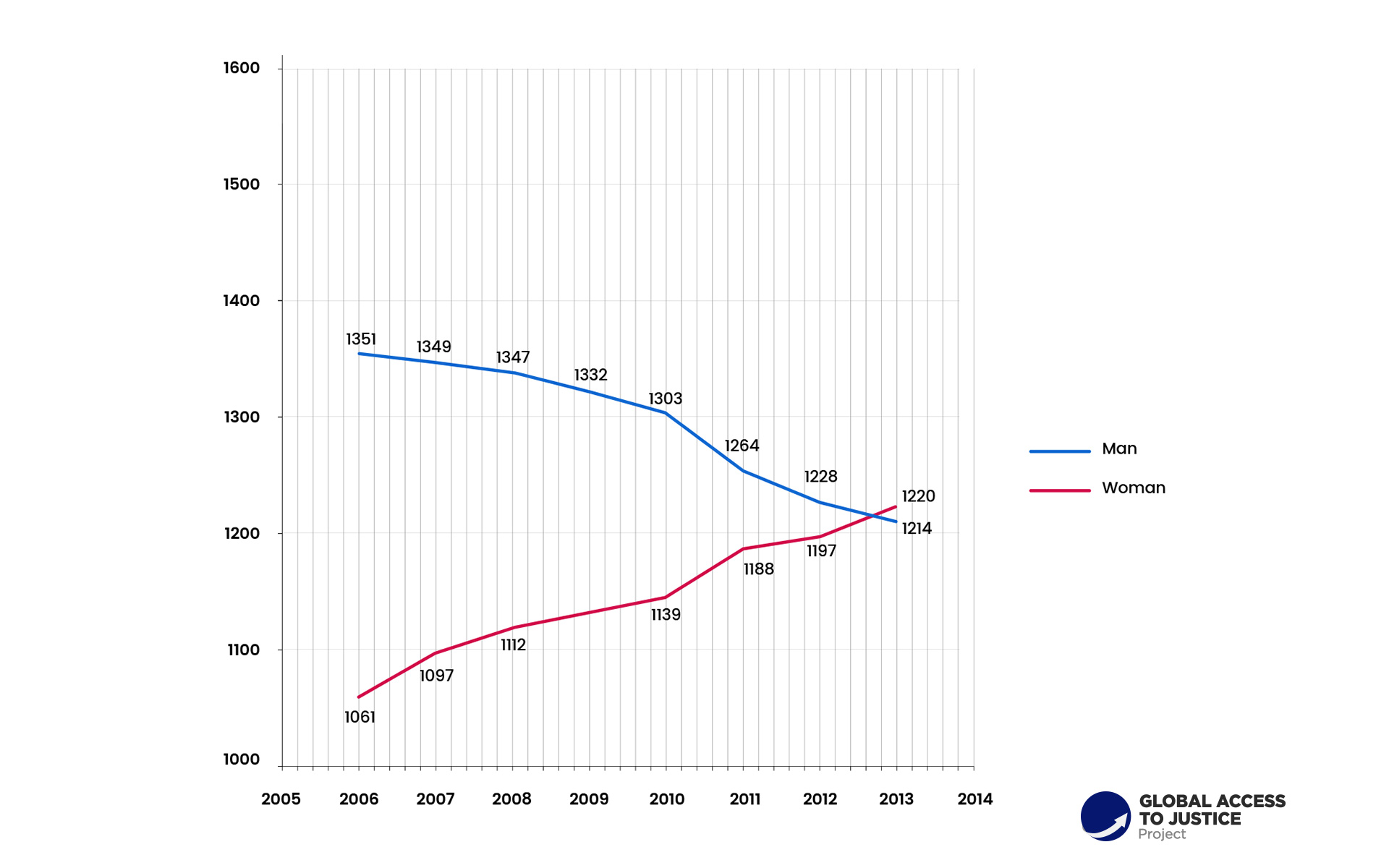

Between 2006 and 2016 the number of male magistrates decreased 12 per cent and the number of women increased 12 per cent, with the result that women gained parity with men in 2013. Women are higher proportions of magistrates on labour courts (60 per cent), courts of first instance (57 per cent) and parole boards (53 per cent), whereas men still are 86 per cent of the Court of Cassation (Gibens, Hubeau, Rutten et al. 2019).

Chart 07. Number of magistrates

Source: Gibens, Hubeau, Rutten et al. 2019

Source: Gibens, Hubeau, Rutten et al. 2019

2.5.1. Judge

In 2016 there were approximately 1578 judges in Belgium. With 14 judges per 100,000 inhabitants, Belgium is one of the leaders in the number of judges compared to our neighbouring countries.

Under Articles 144 and 145 of the Constitution, disputes about civil rights belong exclusively to the competence of the courts, and disputes concerning political rights belong to the competence of the courts except where otherwise provided for by the law.

A court or other body capable of rendering judgment can be established only by statute. Under Article 146 of the Belgian Constitution, no extraordinary courts or commissions may be created, no matter what they may be called.

Judicial independence is regarded as one of the core aspects of the principle of separation of powers. The Constitution contains several safeguards to ensure that judges remain beyond the grasp of other branches of government. Article 151 of the Constitution explicitly recognises the independence of judges in the exercise of their jurisdictional competences (Popelier and Lemmens, 2015). The fact that judges are independent, does not mean that they cannot be evaluated and possibly sanctioned (if they do not function properly). Since 1999, judges and public prosecutors are subject to the same evaluation system (art. 151, §6 of the Constitution).

Judges are appointed for life. They retire at an age determined by law and receive a pension provided for by law. A judge can be deprived of his or her position or suspended only by a court judgment (art. 152 Constitution). Judges are, contrary to public prosecutors, independent in the way that they do not belong to a hierarchic corps and are not accountable to anyone.

A judge can be transferred only by appointing him or her to a new position and only with his or her consent (Article 152 of the Constitution).

2.5.2. Public prosecutor

In 2016 there were approximately 858 public prosecutors in Belgium. This equates to 7,61 public prosecutors per 100,000 inhabitants.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office (PPO) is competent for the general application of the criminal law. It is in charge of the pre-trial investigation and decides whether or not to start criminal prosecution. It is responsible for evidence gathering and it is responsible for the execution of the judgments.

Members of the PPO are obliged to follow the orders and instructions of the Minister of Justice. The hierarchic accountability of members of the PPO towards their superiors is limited to their superiors’ written instructions. At trial, they are free to act as deemed appropriate and request the application of the law conscientiously (“The pen is slave, the word is free”). In practice this means that the hierarchical dependency of the prosecuting magistrate is most present during the pre-trial stage (van Puyenbroeck and Vermeulen 2008).

Members of the PPO are appointed and dismissed by the King (article 153 of the Constitution). Due to the fact that they are dismissible and relocatable and that they are part of a hierarchic corps, they are less independent than judges.

2.6. No shortage of legal services

There is no shortage of legal services in Belgium. On the contrary, there is now even a debate as to whether there are not too many attorneys in Belgium. Very recently, newspapers reported some staffing difficulties for public prosecutors.[9]

2.7. The impact of COVID 19 on the Belgian judicial system

As a general rule, the Belgian courts and tribunals were closed during lockdown and only urgent cases were dealt with (e.g. summary proceedings, urgent family matters, etc.). Filing of claims and documents had to be done online via e-deposit (the electronic platform of the Belgian courts).

A Royal Decree[10] was issued and the written procedure became temporarily the rule for civil cases (or criminal cases with civil interests) for hearings scheduled between 11 April 2020 up to 3 June 2020. In addition, limitation periods and procedural deadlines expiring between 9 April 2020 and 3 May 2020 were extended.

The fact that written proceedings became the rule was in practice tempered by the fact that many courts organised online hearings. The online hearings were evaluated positively both by judges and attorneys.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure[11]

Although civil and criminal courts are both in the same “ordinary” court system, it must be stressed that criminal cases have a specific “launch”, with a pre-trial phase. The Belgian criminal procedure consists of two main stages. The investigation phase or pre-trial phase is said to be inquisitorial because the investigation is in writing, secret and non-accusatorial. The pre-trial investigation is not executed autonomously by the police but is led by the Public Prosecutor. For issuing enforcement orders (to issue a warrant for a house search, a warrant for a telephone tap or to grant a witness full anonymity…) a specially competent Investigating Judge exists. When involved, the Investigating Judge will actively lead the investigation. In this stage, the suspect is not expected to actively participate in the evidence gathering. The investigative proceedings are put in writing and are bundled in a criminal file which will serve as the basis for the second stage, the trial stage.

The criminal prosecution proceedings or the trial stage is said to be accusatorial because its proceedings are public, oral and accusatorial. The judge plays a more passive role than the Investigating Judge during the pre-trial stage and the equality of arms is guaranteed to a large extent. Nevertheless, the trial proceedings still have considerable inquisitorial characteristics. The trial stage is based mainly on the investigative proceedings executed during the pre-trial stage and bundled in the criminal file. The judge will usually already have prepared the case on the basis of the file. The judge will lead the trial and will determine if certain additional inquiries are necessary. As a result, the information gathered during the pre-trial stage will weigh considerably at the trial stage.

Both stages are governed by the Code of criminal procedure (1867).

Accordingly to the different stages the criminal courts can be divided in three categories: investigative courts, trial courts and courts for execution of sentences (the Sentence Enforcement Court). The investigative courts are divisions of the Court of First Instance (the Judicial Council (de Raadkamer / la Chambre du Conseil)) and the Court of Appeal (the Chamber for Indictments (Kamer van Inbeschuldigingstelling / la Chambre des Mises en Accusation)). They form the interface between the pre-trial phase and the trial stage. The investigative courts have three different tasks. Firstly, the investigative courts control whether there are sufficient indications of guilt to bring the suspect before the trial judge. Secondly the investigative courts control the regularity of the investigative actions. Thirdly, a final important function of the investigative courts is to control the pre-trial detention. The trial courts (the Criminal Courts) are competent for judging the merits of the case. The Sentence Enforcement Courts are responsible for the enforcement of criminal penalties and deal among other things with requests for conditional release, but also can suspend or revoke the conditional release. In Sentence Enforcement Courts a professional judge is assisted by two lay judges, one specializing in penitentiary matters and the other in social reintegration.

3.1.1. The investigation phase or pre-trial phase

The police investigate infringements and perpetrators and gather evidence. Where the police suspect the existence of an infringement, they notify the Public Prosecutor who decides (i) either to close the file without further action; (ii) or to continue the enquiries himself (standard investigation); (iii) or to appoint an Investigating Judge, asking him to investigate a specific fact and not one person in particular (judicial investigation). A distinction has to be made between the investigation led by the Public Prosecutor (which is the standard) and the investigation led by the Investigating Judge (judicial investigation).

The Public Prosecutor has less extensive investigative powers than the Investigating Judge. The Investigating Judge or the Public Prosecutor directs the enquiries and gives instructions to the police who carry out the investigations (interviews, searches, DNA samples, etc.).

Police arrest. The police have the authority to deprive a person who has committed an infringement or who is suspected of having committed an infringement of his liberty for 24 hours. After this period the person has either to be released or to be placed into custody.

Custody. If the Public Prosecutor decides that the person should be placed into custody, he will request the Investigating Judge to issue an arrest warrant. The investigating judge is not obliged to issue an arrest warrant. He can decide to release the person (on bail, with or without conditions). When the Investigating Judge decides to place the person in pre-trial custody, the investigation automatically becomes a judicial investigation. During the investigations, the Investigating Judge may issue an arrest warrant on certain conditions: (i) the existence of serious indications of guilt; (ii) facts listed as punishable by at least one year’s imprisonment and (iii) absolute necessity for public safety. If the maximum penalty applicable does not exceed fifteen years’ imprisonment, the warrant can only be issued if there are serious reasons to fear that the accused will (i) fail to attend their trial (i.e. absconding); (ii) tamper evidence or interfere with witnesses; (iii) commit another infringement; or (iv) be in danger of others or themselves. However, the decision to keep the defendant in pre-trial detention is reviewed by the Judicial Council (a chamber of the Criminal Court) on a regular basis (usually every month). The accused must appear before the Judges’ Council Chamber of the Court of First Instance within five days of the issuing of the arrest warrant, and then every month, or every two months from the third decision to maintain pre-trial detention or every three months in the case of a crime reduced to a misdemeanour by statute, until the judicial investigation is closed.

The accused’s right of appeal, which is confined to certain procedural matters, is exercised before the Chamber of Indictments of the Court of Appeal.

The time served in pre-trial detention will be considered as part of the sentence.

3.1.2. The trial stage

In the standard investigation, the public prosecutor can decide to: (i) close the case; (ii) propose a settlement (minnelijke schikking/résolution à l’aimable) to the offender – if the offender accepts the proposal and compensates the damage, the case will be closed; (iii) propose mediation in criminal cases (bemiddeling in strafzaken/médiation dans les affaires pénales) or (iv) send the case to court. In the latter case, the case will then be brought before the Police Courts or Criminal Courts by a ‘direct summons’. If the victim is a civil party to the criminal proceedings he or she will be informed of the public prosecutor’s decision. A direct summons can also be done by a ‘civil party’ (i.e. the victim), which automatically brings the case before a trial court. A direct summons is only possible when there has been no judicial investigation.

If a judicial investigation occurs the Investigating Judge must forward the file to the pre-trial division of the court, the Judicial Council (raadkamer/chambre du conseil). The court hearings in the Judicial Council are held in camera / behind closed doors, so the press and the public may not be present. This pre-trial division can decide to (i) close the case, if it considers that there is not enough evidence against the defendant or that no offence has been committed; (ii) refer the case to court for trial, if it considers that there is enough evidence to bring the defendant to court; (iii) commit the offender to a specialised mental institution if he or she is mentally ill or in a serious state of mental deficiency which makes him or her unable to control his or her acts (in this case the defendant can request a public hearing) or (iv) suspend judgment. The Judicial Council can decide to suspend judgment only when the defendant has not been previously sentenced to more than six months’ imprisonment. The Judicial Council will set a probation period of no more than five years, during which the offender will have to comply with a number of conditions If he or she reoffends or does not comply with the conditions within the probation period, the court can decide to reopen the case. A judicial investigation can only be closed by an investigating court, which can refer the defendant to the trial court by a referral order.

The most serious offences (de facto those where murder or attempted murder is involved) are brought before a jury (the Assize court). The investigating court in first instance cannot in itself refer a person to the Assize court but can refer the file to the Prosecutor-general (article 133 CPC). The Prosecutor-general then has the task of bringing the case before the investigating court in appeal. If the ‘accused’ is referred by the investigating court in appeal by an indictment, the Prosecutor-general has to make the formal ‘act of indictment’ in which the nature of the offence, the underlying fact and all possible aggravating or mitigating circumstances are contained.

Trial. When the case has been brought before the trial court, a date will be determined on which the case will be pleaded.

When the trial begins, the judge in charge of the case will interrogate the defendant if he is present. Before the Police Court and the Criminal Court, unless specified otherwise in the summons, the defendant does not have to be present and can be represented by an attorney. If the defendant is not present and is not represented by an attorney either, a judgement in absentia will be rendered.

Next the court will hear the witnesses, if any witnesses are called. In Belgium it is not automatic to call witnesses and it often does not happen, except in the most serious cases. If witnesses are called, the court will question them and if the attorney of the defendant has questions he passes them on to the court. There is no direct cross-examination of the witnesses.

Then, the victim, acting as civil party, may plead.

Subsequently, the Public Prosecutor will present his case.

At the end defendant and/or his attorney will be given the opportunity to respond to the arguments made by the civil party and/or of the Public Prosecutor. The importance of the plea in criminal cases should not be underestimated. During the pleas one can often get a good indication of the court’s opinion.

At the end, the court will inform you of the date when its decision will be known.

During trial the defendant can be kept in custody as long as the conditions set out above are met.

Limitation period and the reasonable-time requirement. No specific limitation period exists with regard to the police investigation or the investigation phase. As the prescription period starts to run from the day the infringement was committed or ended, prescription continues to run during pre-trial phase. When assessing the reasonable-time requirement, the judge can eventually take into account the length of the pre-trial phase.

The periods of limitation of the criminal proceedings are listed in Article 21 of the Preliminary Title of the Code of Criminal Proceedings (Deruyck & Vanladeghem, 2020). The prescription period starts to run from the day the infringement was committed or ended. With regard to offences (small criminal infringements) a 6 months prescription period applies. Malpractices (mediocre types of criminal infringements) prescribe after 5 years. For crimes (the most serious types of criminal infringements) in general a prescription period 10 years applies. For some crimes (such a s genocide or war crimes), criminal proceedings are not time-barred and for some crimes (e.g. manslaughter, murder…) the prescription period is extended to 15 or 20 years.

Article 21ter of the Preliminary Title of the Code of Criminal Proceedings expressly allows the judge to take into account the reasonable-time requirement ex article 6 ECHR. If the length of the criminal proceedings exceeds a reasonable period, the judge can pronounce a simple conviction without any sentence or he can condemn the defendant to a sentence which may be lower than the statutory minimum.

Compliance with ECHR. Compared to civil proceedings, the influence of the case law of the European Court of Human Rights was much more important. By way of illustration, some ECtHR judgments that had a major impact are briefly discussed.

As for many other European countries the Salduz-judgment[12] was a game changer. As it is well known the European Court established in this case that the right under Article 6(3)(c) ECHR becomes applicable as soon as there is a ‘criminal charge’ – a concept autonomously interpreted by the Court – and, in particular, from the time of the suspect’s arrest. Every suspect or accused thus enjoys, as a rule, a right to prior (confidential) legal consultation and physical presence of his or her attorney while in police custody and during the whole pre-trial phase of criminal proceedings in relation to all interviews, including the very first police interrogation, and other investigative acts in which they participate. In accordance with the consecutive European Directives, Belgium embedded the right to assistance of an attorney from the time of the suspect’s arrest in its legislation and an on-call service was organised within the Bar.

A second recent case which had a major influence on the Belgian criminal justice system, is the case of Taxquet v Belgium.[13] The European Court held in this case held that the verdict on the national level, issued on the basis of trial by jury (a system used in Belgium for the more severe crimes, dealt with by the Court of Assize), was not sufficiently motivated and thus ran counter to Article 6 ECHR (right to a fair trial). The Court considered that the motivation in a criminal judgment both protected the accused and also formed a bulwark against arbitrariness. In the Belgium system (and several others) a jury could only answer the questions posed to it by yes or no or guilty or not guilty. In the aftermath of this decision the proceedings in front of the Court of Assize were altered. After the jury has answered the questions posed to it in a first deliberation, the trial judge will attend the jury’s second deliberation to help draft a judgment which does sufficiently motivate.

Lastly, an important concern with regard to the Belgian criminal justice system has been the hopeless situation of offenders with mental disorders. The ECtHR judged that there was a structural breach of the Convention by Belgium with regard to the detention of offenders with mental disorders in a prison environment unsuited to their therapeutic needs.[14] The Court decided to apply the pilot-judgment procedure in the case (as 50 similar cases were pending before the ECtHR), giving the Government two years to remedy the general situation and adjourning proceedings in all similar cases for two years. Belgium was required to organise its system for the psychiatric detention of offenders in such a way that the detainees’ dignity was respected. A new Involuntary commitment act came into force on 1 October 2016, one of the aims of which was to improve the legal position of offenders with mental disorders and to raise the threshold for commencing involuntary commitment. Shortly afterwards, a master plan for prisons and the opening of specialised psychiatric detention centres was approved.

3.2. Civil Procedure

There are two court branches within the Belgian system: the administrative courts and the ordinary courts.

The administrative courts deal with matters relating to administrative law; that is, the organisation, the functioning, and the control of the executive. The Council of State is the highest administrative court. It can overturn decisions of government officials and regulations of other administrative authorities and state agencies on the basis of excess or abuse of power or if it considers that essential procedural requirements are violated (it include matters environmental disputes, civil service law…). The Council of State also acts as a Supreme Court for decisions of other specialised administrative courts, such as the Council for Alien Disputes (competent for cases with regard to the residence status of aliens), the Council for Building Permit Disputes or the Council for exam disputes (an administrative court that hears cases with regard to decisions on the progress of studies taken by institutions of higher education in the Flemish Community).

The ordinary courts have jurisdiction over civil and criminal matters. The jurisdiction with regard to civil matters includes business disputes, labour and social welfare cases and family disputes.

Civil proceedings in Belgium are governed by the Code of Civil Procedure (1967).

Party autonomy combined with an active role of the judge. Belgian civil procedure is guided by the principle of party autonomy. The parties set the limits of the dispute. They are solely responsible for specifying the relief sought and the court cannot grant a claim that was not expressed or grant more than was claimed. Nevertheless, the judge has a case management responsibility and a certain “inquisitorial” or “investigative” role in relation to the facts and evidence (Taelman en Van Severen, 2018). The judge must ensure that the procedural rules are respected and he can direct and instruct the parties in order to make sure that the progress of the proceedings is maintained and a judgement can be rendered within a reasonable delay. The investigative role of the judge is threefold. First, a judge can deduce extra information from the facts or from the evidence presented by the parties, even when none of the parties has relied on this information. Second, a judge has the power to ask appropriate questions to the parties during the hearing. Third and most far-reaching, is the power of the judge to order any additional investigation measure (e.g. forced submission of documents, appointment of an expert witness…).

Start of the proceedings. Proceedings can be initiated either by a writ of summons[15], by a petition / inter partes application[16], by the voluntary appearance of the parties[17] or by an unilateral application[18]. In principle proceedings commence when the applicant (or its lawyer) asks the court bailiff to serve the summons to the defendant. The voluntary appearance, the inter partes application and the unilateral application are exceptions to this general principle.

Introductory Hearing. Cases that only require limited debate, such as the recovery of undisputed claims and requests for the appointment of a court expert, will normally be decided at the introductory hearing or shortly after.[19]

In cases that require a more extensive exchange of arguments, the parties can always agree to a calendar to submit their respective arguments. If at the introductory hearing the parties do not agree to such a calendar, or to an adjournment of the case, the court should normally establish a calendar itself.[20]

If the defendant does not attend the hearing, the judge may render a judgment in default / in absentia.[21]

The claimant serves his documentary evidence on the defendant and must ensure that the defendant receives the documents.

Hearing. The oral hearings take place after the exchange of briefs and exhibits by the parties. If a calendar was set at the introductory hearing, the hearing date is known from the start. If this was not the case, the parties can request the court to fix a hearing date.

Civil hearings are open to the public. Parties may plead in person or through their attorney (or exceptionally through another legal representative).

Judgement. After the oral pleadings, the judge will deliberate and a written judgment should normally be given within one month.[22]

Urgent matters. The presidents of the Courts of First Instance may provisionally rule on all urgent matters (even in administrative matters). The presidents of the Labour Tribunals and the Business Courts have a concurrent competence to deal with urgent matters which fall in the normal scope of their jurisdiction.[23] In order to make use of these summary proceedings (kort geding / les procédures en référé), two conditions must be met. Firstly, the request has to be urgent, meaning that an immediate decision is desirable to prevent (further) harm or serious discomfort. Secondly, during summary proceedings the president can only order provisional measures (Taelman & Van Severen, 2018). The interim measures ordered by the president of the court cannot decide on nor cause any prejudice to the merits of the case. The interim measures have a limited effect in time and shall only apply until a decision on the merits of the case is rendered.

Conciliation or settlement of a dispute during formal civil legal proceedings. Currently the Judicial Code explicitly states that the judge promotes an amicable settlement of disputes at any stage of the proceedings.[24] With the exception of summary proceedings, the judge may, at the introductory hearing (or during a special hearing on a nearby date), question the parties about the way in which they have tried to resolve the dispute amicably prior to the proceedings and inform them of the possibilities to do so. To this end, the court may order the personal appearance of the parties. At the request of one of the parties or if the judge deems it useful, he may, if he finds that a settlement is possible, postpone the case to a later date (which may not exceed one month) in order to enable the parties to examine whether their dispute can be resolved amicably in whole or in part.

Based on the information received during the introductory hearing and in any stage of the proceedings, a judge can refer parties to mediation[25] or collaborative negotiations[26] if at least one of the parties agree. This means that a mediation or collaborative negotiations can be imposed on one of the parties.

The Judicial Code also states that it is the duty of the judge to conciliate the parties. In some matters (e.g. labour disputes) a preliminary conciliation attempt is obligatory. When a conciliation attempt is obligatory, this often is a mere formality. The obligatory conciliation attempt is the only example under Belgian law in which parties are required to rely alternative dispute resolution before having access to court. A judge can attempt to conciliate the parties in any stage of the proceedings.

Compliance with article 6 ECHR. The Belgian civil legal system does comply with the rule of law and respects due process. The main concern is compliance with the reasonable-time requirement. All reforms of the Judicial Code had as an important aim to reduce the judicial backlog. Despite the efforts made the judicial backlog is still considerable at the level of the courts of appeal and in cases in which a court expert has been appointed. The case law of the ECHR that affected the Belgian civil legal system the most, was the case Borgers/Belgium.[27] This case led to the reform of the Judicial Code with regard to the advisory role of the Public Prosecutor’s Office in civil cases. Parties were granted the right to respond (in writing) to the advisory opinion of the Public Prosecutor’s Office in civil cases and in Supreme Court proceedings the Public Prosecutor was excluded from the deliberations of the judges of the Supreme Court.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

Under Belgian law use is made of the following ADR techniques: conciliation, arbitration, ombudsman, mediation and collaborative law.

Conciliation. Under Belgian law conciliation generally refers to the attempts made by the court to settle a dispute in the course of judicial proceedings concerning the dispute in question.[28] Traditionally, the Belgian legislator attached great importance to the so-called conciliating role of the judge. In practice, the judicial history reveals a considerable gap between the law in books and the law in action. Although conciliation is always optional and in some cases mandatory[29], this conciliatory task was, for a long time, almost solely implemented with success by the Justice of the Peace Courts (Raes 2019).

Arbitration. Belgium is a party to most of the international conventions with respect to arbitration, including the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards. Belgian arbitration legislation is based on the Uniform Law of the Strasbourg Convention of 28 January 1966 and its later amendments. As a general rule, any dispute which arises out of a civil or commercial relationship may be submitted to arbitration as far as it regards a ‘pecuniary claim’ or a ‘non-pecuniary claim with regard to a matter in which a settlement agreement may be made’ (this explains why family disputes and other disputes governed by rules of public policy cannot be subject of arbitration).[30] This general principle is, however, subject to exceptions. Disputes may not be submitted to arbitration if specific laws prohibit this (e.g. consumer disputes, housing rental disputes with regard to somebody’s main residence…). Arbitration is always a consensual process under Belgian law.

If a dispute that is subject to arbitration is brought before a court, the court must, upon request of either party, rule that it lacks jurisdiction, unless the arbitration agreement is invalid or has ceased to exist. In an arbitration procedure[31], the arbitrator(s) pronounce(s) a judgement on the dispute as a judge would. The arbitrator(s) give(s) a decision in writing, the ‘arbitral award’. A copy of the award is sent to the parties to inform them of the decision. A second copy is deposited at the registry of the tribunal of first instance. The parties have to carry out the award. If one of them does not, the other party can ask the president of the tribunal of first instance to impose its implementation (= exequatur).

Ombudsman. An ombudsman’s mission is to analyse individual complaints concerning the functioning of public institutions (federal public services, pensions, Belgian railways, Communities, Regions, municipalities…) or concerning specific sectors (post office, insurances, banks, telecommunications…) and to deliver opinions. When a company or public institution does not wish to follow the ombudsman’s opinion, they have to give their reasons. The ombudsman also plays a preventive role as it also makes suggestions and recommendations to offer long-term solutions. The services of an ombudsman are free of charge.

Worth mentioning is the Consumer Mediation Service[32], created in accordance with the European directive 2013/11/EU of 21 May 2013 on alternative dispute resolution for consumer disputes. The Consumer Mediation Service is an independent public service which (i) informs consumers and companies about their rights and obligations, particularly about the options available for the out-of-court settlement of consumer disputes, (ii) receives all requests for the out-of-court settlement of consumer disputes and, if applicable, either transfers them to another qualified entity competent in the matter, or handles them itself. The Consumer Mediation Service intervenes in all requests for out-of-court settlements of disputes when no other qualified entity is competent.

Mediation.[33] There are three types of mediation in Belgium. Private mediation is completely independent from judicial proceedings and often takes place without any subsequent court proceeding. The mediation takes place without the interference of a judge. Court-annexed mediation occurs during the judicial proceedings between the parties and is ordered by a judge in a judgment. It is initiated by the court, but then takes place without any further involvement of the court.

With the exception of private mediation in business disputes, only mediators certified by the Federal Mediation Commission, can act as a mediator. Certification is granted after completing a specific training of 130 hours.

Finally, Belgium law has one example of judicial mediation. In disputes pending before the Family Court a case can be referred to the Chamber of Amicable Settlement. Judicial mediation is more intensely connected with the court as an institution in terms of venue and personnel. In the Chamber of Amicable Settlement a judge will act as a mediator between the parties. The judicial mediation is performed by another judge than the judge with adjudicatory competence in the specific case.

In principle, the initiative comes from (one of) the parties involved in the conflict in all three types of mediation. Exceptionally, in a court-annexed mediation, a judge can in certain stages of the proceedings refer parties to mediation if at least one of the parties agree. [34]

Any dispute which arises out of a civil or commercial relationship may be submitted to mediation as far as it regards a ‘pecuniary claim’ or a ‘non-pecuniary claim with regard to a matter in which a settlement agreement may be made’. Settlement is possible as long the dispute is not governed by rules of public policy. Although family disputes are essentially governed by rules of public policy, exception is made for family disputes, which can be subject to mediation. Also disputes to which the government is a party may be the subject of mediation[35]

If the parties request it, and provided that the mediator is certified, the settlement agreement can be ratified by the court competent of handling the dispute. It will then have the same legal value as a court sentence and be binding.

Collaborative law.[36] Since January 2019 a legislative framework for collaborative law entered into force. The new provisions were embedded in the Judicial Code. Article 1738 of the Judicial Code describes collaborative law as a voluntary and confidential dispute resolution process by means of negotiation, in which both the parties to the dispute and their attorneys are actively involved.

This ADR-method can only be used by collaborative attorneys with the required accreditation, obtained after following a specific training. The two Regional Bar Associations are responsible for the training and accreditation of collaborative attorneys. The collaborative attorneys act within an exclusive and limited mandate of assistance and offer advice in order to reach a settlement between the parties to the dispute.

Collaborative law is always voluntary and can never be imposed by a judge without consent of all parties. Either the parties jointly request the referral to collaborative law or the judge takes the initiative, in which case both parties must give their consent.[37]

Policy drivers behind the development of ADR processes in Belgium. The evolution towards a more active judge has the necessary effects during the formal settlement of the case. The Law of 18 June 2018 has given the judge the necessary tools to actively direct parties towards an amicable settlement of their conflict. Since the existing amicable resolution processes, such as conciliation and mediation, are now only applied sporadically and with moderate success, the legislator tries to stimulate these alternative processes. The judge would rule only in exceptional circumstances in order to settle the dispute between the parties. Bringing a case to court should thus be regarded as an ultimum remedium. The legislator has made use of this moment to consolidate the active role of the judge. The judge can oblige the parties to make an attempt at mediation before proceeding to adjudicate the dispute.[38] He may also question the parties on the steps they have already taken to resolve their dispute amicably. If they have not yet attempted to do so, the court will inform them of this possibility.[39]

Besides the benefits of the amicable settlement of disputes, the main policy driver behind the active promotion of ADR is the concern that the 19th century judicial system has become to costly in times of austerity

People with limited means benefit from the same (financial) support as if they would have entered into judicial proceedings. They can benefit from the assistance of a pro deo attorney and the costs related to mediation will be supported by the government.

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

It is impossible to give a general overview of all simplification of law over the past decades. Belgium underwent the same developments as many European countries. In accordance with the European Directive 85/374/EEC of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products, Belgium introduced strict (no-fault) liability rules for defective products. Another development is the introduction of “no-fault” divorce laws, which made it over the years more and more flexible to get a divorce.

In this report we focus on two more recent developments: the introduction of a new recovery procedure for unchallenged claims in business disputes and the introduction of a “no-fault” compensation law with regard to healthcare.

Recovery Procedure for Unchallenged Claims. A summary order for payment procedure was introduced in 1967, at the same time of the enactment of the Belgian Judicial Code. The introduction of this procedure aimed at introducing a quick and simple procedure for the collection of small claims and eliminating the possibility for a debtor to delay payment by way of abusive and frivolous arguments. The procedure is open to claims falling under the jurisdiction of the Justice of the Peace, the Police Court, or the Business Court. The claim must relate to an established debt of an amount not exceeding € 1.860. The summary order for payment procedure was (and still is) a voluntary and not successful procedure and this led to the introduction to a new procedure for business claims (Voet, 2015). In order to tackle the problem of late payment, a new procedure was introduced in 2016. This recovery procedure for unchallenged claims should allow a faster and cheaper collection of undisputed invoices. The following elements contribute to this goal. Firstly, it is an administrative procedure. Where previously an unpaid creditor had to pass through the court, it is now sufficient to call in a lawyer and bailiff. As a result, the recovery procedure will progress more quickly and a creditor can, in principle, already claim the amount due after 1 month and 8 days. Secondly, the new procedure eliminates a whole series of costs associated with recovery, making it cheaper than the traditional procedure. Finally, a solvency check of the debtor can be carried out by the bailiff at the start of the proceedings. In this way, the creditor can make an informed assessment of the advisability of initiating proceedings.

“No-fault” compensation law with regard to healthcare. An interesting example of a no-fault compensation law in Belgium is the law on the compensation of damages resulting from health care[40] This law introduces a no-fault liability for damage caused by medical acts. The victim no longer has to prove that the healthcare provider made a mistake. Victims or their heirs can submit an application for compensation to the Health Care Accident Compensation Fund.

The fund determines whether the damage results from an event giving rise to the liability of a health care provider or from a medical accident without liability.

The procedure is (i) free for the victim who submits a claim; (ii) quick: the victim must be compensated within one year, (iii) simplified: no evidence needs to be gathered, because the compensation fund gathers all the information and (iv) amicable: no need to go to court.

The procedure via the fund is optional and non-exclusive: the victim always keeps the option of going directly to court instead of having recourse to the fund. The victim can also contest the fund’s proposal in court. If the fund is of the opinion that the damage was caused by an event giving rise to the liability of a healthcare provider, the healthcare provider (or its insurance company) must compensate the victim.

The victim will be compensated quickly, whether or not the liability is disputed. If the insurer disputes the healthcare provider’s liability, the fund itself reimburses the victim – insofar as the damage is sufficiently serious – and then recovers the costs from the insurer. The victim is thus quickly compensated.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

The right to access to a judge before a court (and as a consequence, the right to access justice) is not explicitly mentioned in the European Convention on Human Rights. However, it’s generally agreed that this right is implicitly guaranteed by article 6.1. of the European Convention on Human Rights. That article concern the right to a fair trial. The scope of this article has been assessed by the European Court of Human Rights. The jurisprudence has also developed justified restrictions to this right. This article enshrines the right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial.

Article 47 of the European Charter on Fundamental Rights is also relevant here. Article 47 states: Everyone whose rights and freedoms guaranteed by the law of the Union are violated has the right to an effective remedy before a tribunal in compliance with the conditions laid down in this Article.

Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal previously established by law. Everyone shall have the possibility of being advised, defended and represented. Legal aid shall be made available to those who lack sufficient resources in so far as such aid is necessary to ensure effective access to justice.

In the Belgian legal system, article 23 of the Constitution sets out citizens’ fundamental social and economic rights. The purpose of these rights is to give citizens the opportunity to live in accordance with the principle of human dignity. The right to legal aid or assistance is one of the fundamental rights set out under article 23. In Belgium, the general principle of the right to legal aid or assistance is a constitutional provision. This has been further elaborated upon by the Law of 23th of November 1998, which is an ordinary statute.

4.1. European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights has been directly incorporated into the Belgian legal system. The legal system has to respect and fulfil the requirements of this treaty, since the legal force of the treaty is more significant than national legislation.

Although Article 6.1. of the ECHR makes no explicit mention of a right of access to a judge, as early as 1975, the European Court of Human Rights decided that the right of access to a judge is an element of the right to due process (ECtHR 21 February 1975, Golder v. United Kingdom). In the absence of a right to access, the article would be absolutely meaningless.

What exactly does the right to access to a judge entail? First, it means that the parties must have access to a concrete and effective opportunity to submit their dispute to a judge and to receive a ruling on it (ECtHR 4 December 1995, Bellet v. France; ECtHR 19 October 2005, Roche/United Kingdom). Further, they must have access to the decision on this dispute and the reasons underlying it (ECtHR 12 July 2001, Prince Hans-Adam II of Liechtenstein v. Germany; ECtHR 30 October 2003, Ganci/Italy; ECtHR 14 December 2010, Boulois v. Luxembourg). The court may not refuse to resort to certain means, and it must provide justification for the ruling (ECtHR 22 November 1995, Bryan v. United Kingdom; ECtHR 21 June 2016, Al Dulimi and Montana v. Switzerland).

Further specifications include that the relevant basic right must be concrete, practical and effective, and not purely theoretical or illusory (ECtHR 9 October 1979, Airey v. Ireland). This should be clearly defined in the law.

Unlike Article 6.3. of the ECHR, Article 6.1. of the ECHR does not include any general obligation to provide a system of legal assistance. According to the court, free legal assistance is not a necessary condition for a fair process and actual access to the judge. This is because such access can be guaranteed by making the procedures themselves sufficiently simple and accessible. In certain cases, however, legal assistance will be necessary in order to guarantee a fair process. This should be considered from the perspective of the special facts and circumstances of each case, and it should depend on the interest of the case to the appellant, the complexity of the legislation and the procedure, and the possibility of the appellant to defend himself (ECtHR 9 October 1979, Airey v. Ireland; ECtHR 7 May 2002, McVicar v. United Kingdom; ECtHR 15 February 2005, Steel & Morris v. United Kingdom). For cases in which the concrete characteristics of the case necessitate the assistance of an attorney, the government must indeed provide a system of free legal assistance in certain cases. Although the objective should not be to achieve equality of arms between parties, each party should be provided with the opportunity to present its case under circumstances that are not clearly less favourable than are those of the opposing party.

The member states may provide for their own organisation of the right to access to a judge, as guaranteed by the ECHR. Although the ECtHR will not determine the possible limitations, it will monitor their correspondence with the provisions of the charter. Article 6 must be applicable to the dispute; it must involve rights and obligations in the substantive law of the member state concerned; it is a right of a purely procedural nature, such that substantial restrictions are out of the question. The restrictions should not affect the essence of the right. The dispute must pursue a legitimate goal and be proportional to this legitimate goal (ECtHR 21 February 1975, Golder v. United Kingdom; ECtHR 28 May 1985, Ashingdane v. United Kingdom; ECtHR 27 April 2004, Maat v. France; ECtHR 3 June 2004, De Jorio v. Italy; ECtHR 24 June 2005, Lulic & Becker v. Croatia).

4.2. The European Charter on Fundamental Rights

The observance of the fundamental rights in the EU must be effective. This means that individuals whose rights have been violated have the right to an effective remedy. The right to an effective remedy is anchored in Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights. This ensures that, in cases involving the violation of rights that are guaranteed by Union law, individuals are able to approach the judge in order to demand that their rights be observed.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also establishes that everyone is entitled to a fair trial in all legal procedures relating to Union law: ‘Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal previously established by law. Everyone shall have the possibility of being advised, defended and represented. Legal aid shall be made available to those who lack sufficient resources in so far as such aid is necessary to ensure effective access to justice’.

The European Parliament has contributed to the development of the rights of individuals who are suspected or charged in a criminal procedure, such that they have at least the same procedural guarantees in all member states.

° The principle of the assumption of innocence must be observed, suspects or defendants must be able to understand what takes place in criminal procedures and they have a right to interpretation or translation.

° When they are brought before the judge, they must also be informed of their rights and have the right to an attorney. Legal assistance must be provided to individuals who do not have access to sufficient means.

° Additional conditions apply in the case of children who are suspected or charged in a criminal procedure.

° The rights of victims must also be protected throughout the entire EU. The European Parliament and the Council have recently adopted legislation guaranteeing that victims of criminal offences must be treated with respect, that they must receive the protection and support that they need and that they must receive sufficient access to the judge. In EU law, special attention is paid to specific groups of victims, including children, victims of human trafficking and victims of terrorism.

4.3. Belgian procedural law

Belgian civil procedural law does not guarantee the right of access to the judge as such. This right is nevertheless included as a component of procedural law. More specifically, anyone holding a subjective right can bring a lawsuit. In other words, anyone holding a subjective right is entitled to appeal to the judge to demand that a legal obligation be met or that a subjective right be observed. This includes the right to defend an action before the judge concerning these matters. This is an element of a democratic society, and thus also of public order (Court of Cassation 25 April 2002, Arr. Cass. 2002, 1.126, Pas. 2002, 1008).

4.4. Political commitment to access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial

Can we refer to recent statements on these topics by government and public bodies? Under the supervision of the influential King Baudouin Foundation, in 2001 a report on the relation between the citizen and the justice system, a lot of recommendations were made concerning access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial, considered to be one of the cornerstones of a democratic society. This report has been rewritten in 2019, taking into account new developments since the first report, e.g. digitization of aspects within the justice system. Sometimes experts have been asked to write reports on the justice system: the relevant matters often are part of the proposals in these reports (e.g. Erdman & Deleval).

We also can mention preparatory documents of legislative proposals. Debates about these matters in Parliament are rather rare: of course, during the parliamentary procedure which led to the important act of November 23th 1998, these aspects have been discussed. Other parliamentary debates are very casuistic (motivated by concrete events, concrete problems or problems with certain target groups, e.g. refugees or tenants). Since part of the competence for justice matters is transferred to the communities, parliamentary discussions take place in those respective parliaments, e.g. on the first line legal aid in the Flemish or the French Community.

Is this a genuine political commitment? One can say these matters are not put forward at the top of the political agenda.

Let’s have a look into the commitments in the manifestos of political parties. Most of the political parties developed opinions about justice, access to justice and related matters, either in a casuistic way (certain events lead to –immediate- reactions), or in times of general elections.

The right wing parties often concentrate on security issues and how the justice system has to enhance it. The justice system has to be a performing body and fight the lack of sanctions towards criminality. A zero tolerance policy and a stricter execution of sanction is of the essence (NVA). The right-wing parties are convinced that a general change in mentality is needed with regard to the justice system, in which the primary focus is shifted away from the victim and towards the perpetrator. For this reason, the party is calling for a strict four-track policy: prevention; direct, resolute reaction; or, as needed, alternative and effective, non-compressible sentencing (Vlaams Belang).

The Justice Department is increasingly specialising and gaining expertise in order to address even complex crime efficiently. Organised and cross-border crime can destabilise a society. Such serious forms of crime must be addressed in all possible manners: punitively, fiscally and administratively. The level of penalties for participating in terrorist activities should be increased.

Often, political parties focus on the central role of the citizen in the justice system (NVA).

Political parties on the left side combine a discourse about the pivotal role of the citizen in the justice system with a few other priorities. Access to the judge is a fundamental right of every citizen. For many people, however, this fundamental right has remained largely theoretical. In recent years, justice has been increasingly transformed from a basic right into a luxury product. This has resulted in the emergence of a two-speed justice system. In far too many cases, the result of a procedure is dependent on the financial resources of the party seeking justice. Justice must once again move closer to the citizen by making the justice system more accessible, more affordable and more understandable. The justice system should be modernised (and thus digitised), and legal professions should be democratised (Spa).

The justice system is underfunded, and access to the courts continues to be limited, due to financial obstacles being increased and procedures becoming more complicated. Judicial backlog has since become a major problem. Procedures are incomprehensible, and cases drag on for far too long. The system of legal assistance for people with low incomes has become more expensive and more complex, thus making it more difficult for these people to receive free assistance (PvdA).

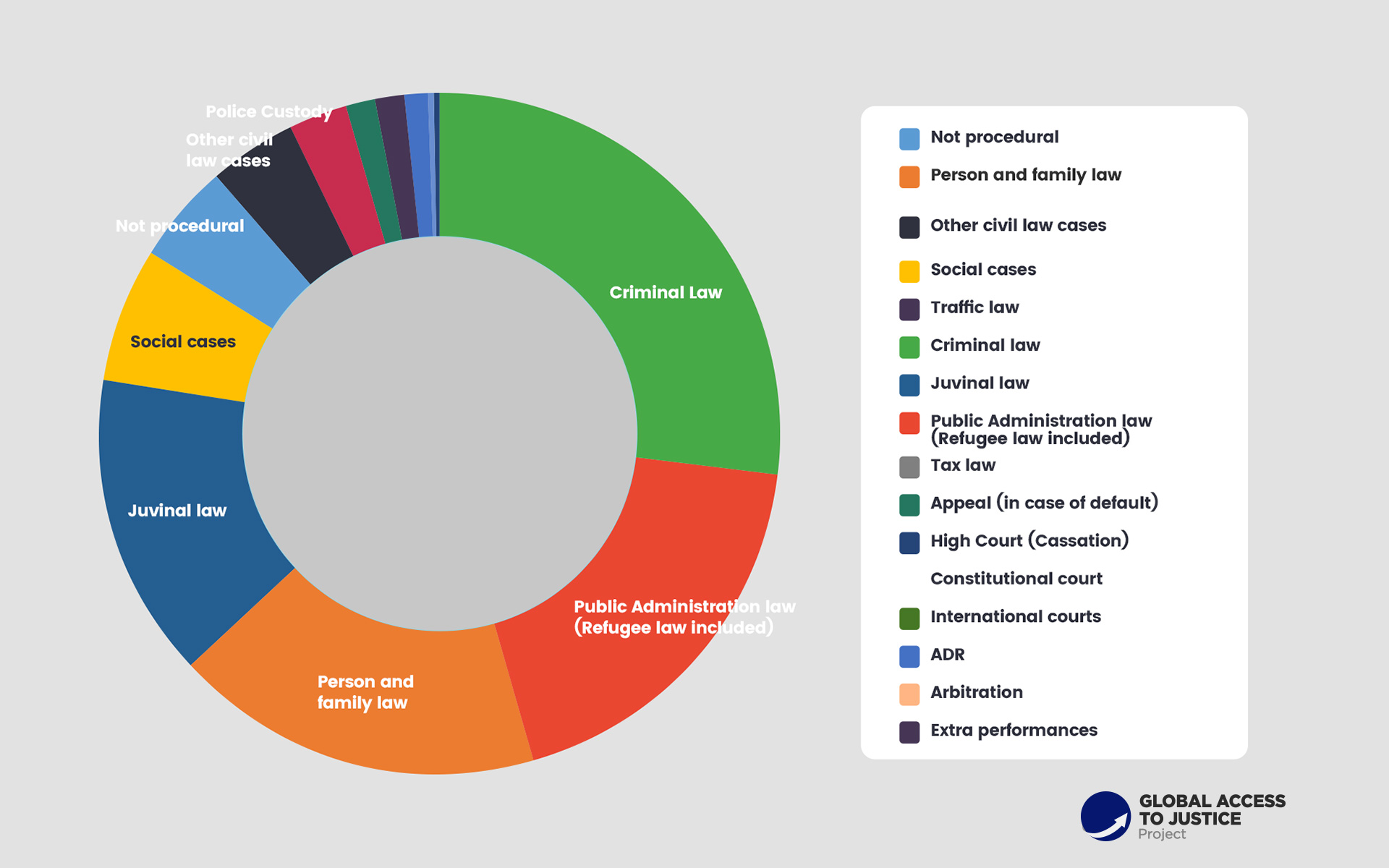

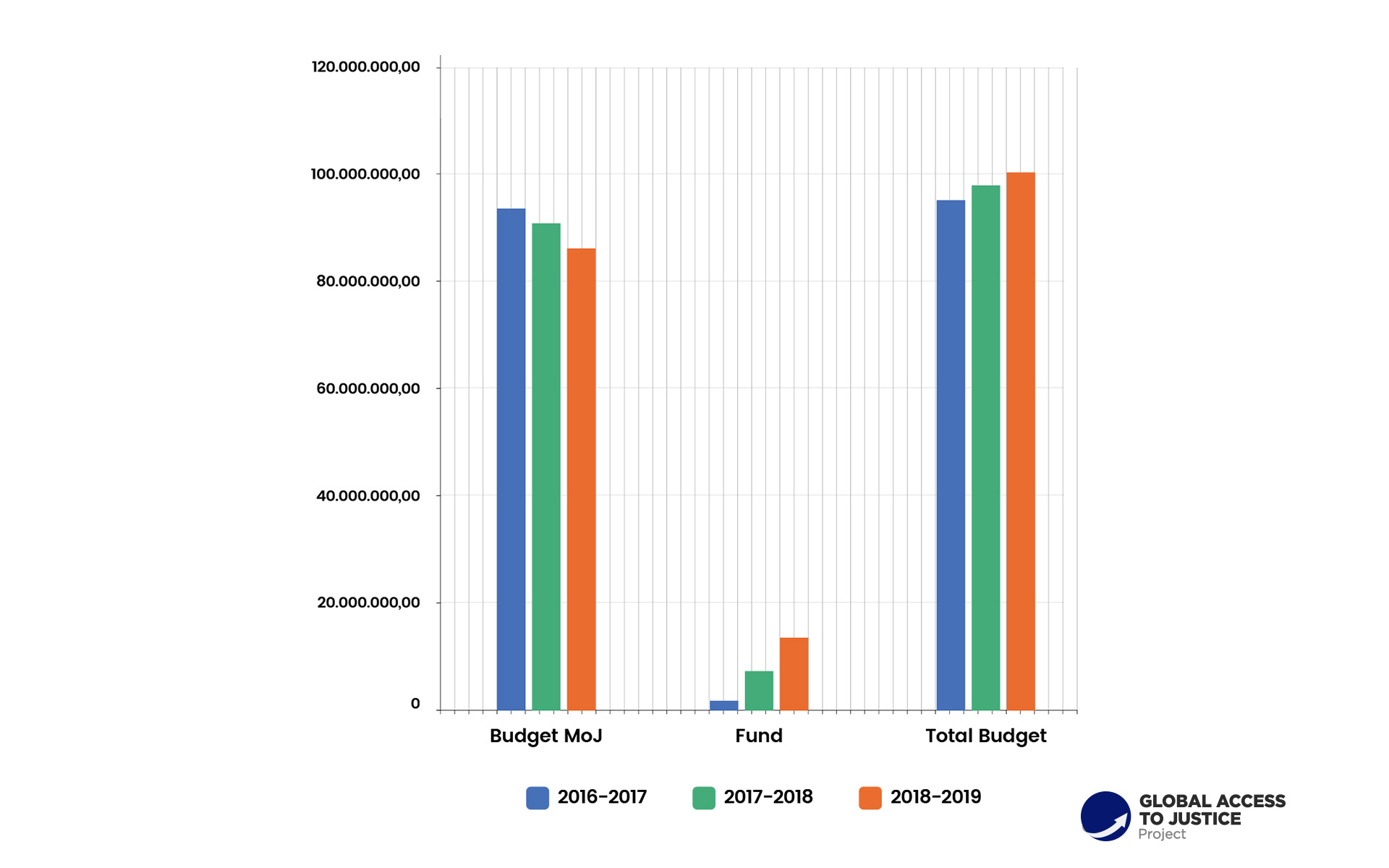

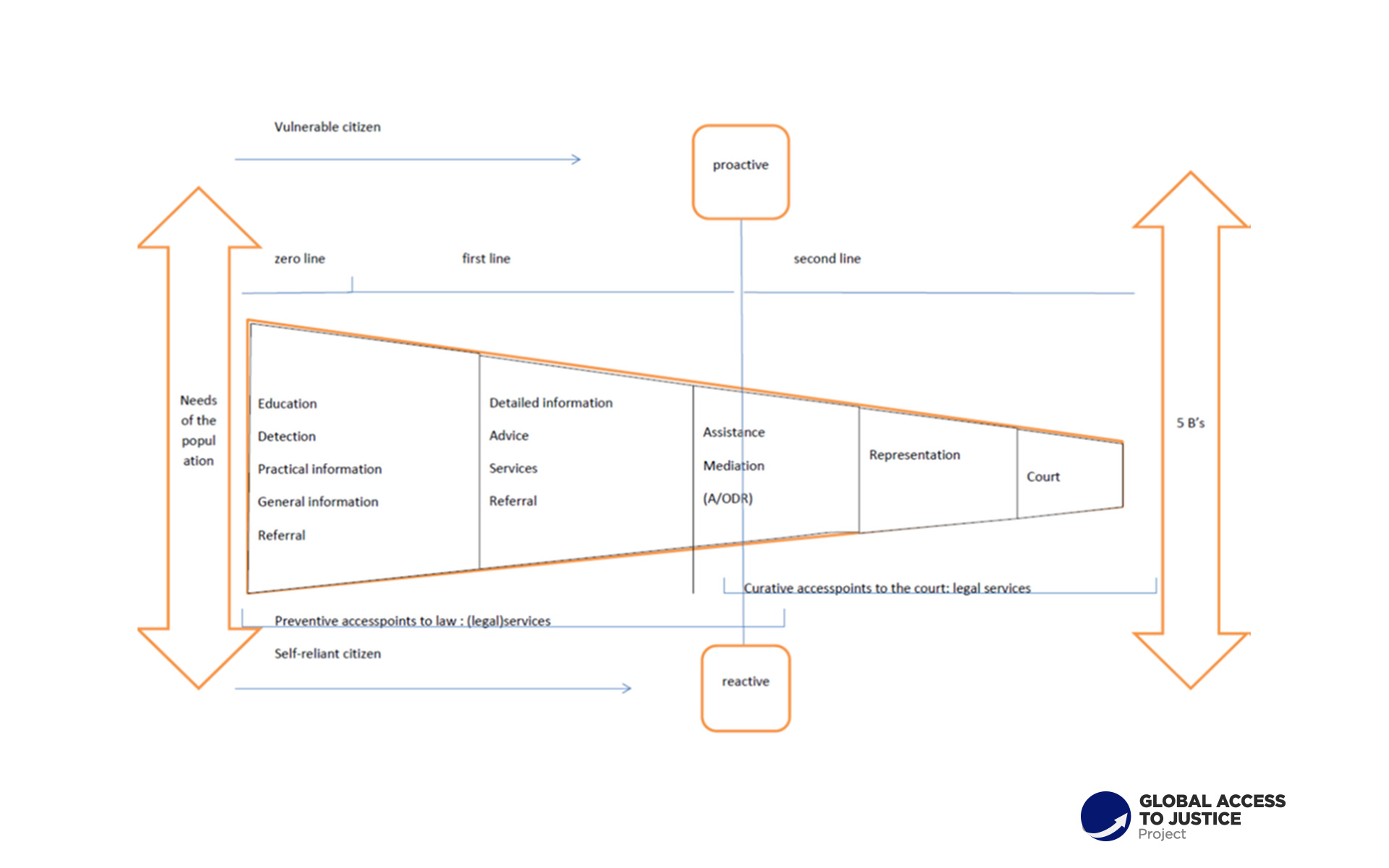

The Parti Socialiste (PS) thinks that an input of a billion euros will be needed for the justice system in five years, and it seeks mandatory legal coverage for all citizens, starting with civil procedures. In the meantime, the second-line legal assistance must be re-calibrated to ensure that the most vulnerable people will be able to use the services of the legal profession free or at reduced cost (PS).