National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

The World Population Data estimates the population of Zimbabwe to be 14 654 468, a figure slightly above 14,5 million people.[1] Zimbabwe has 16 official languages that include sign language, although English, Shona, and Ndebele are the most spoken languages.[2] When the Constitution was adopted in 2013, the people of Zimbabweans committed themselves to make the Constitution the fundamental law of the land.[3] The three pillars of government, that is, the executive, legislature and judiciary, derive their powers from the people of Zimbabwe under the entrenched constitutional principle of separation of powers.[4] Governmental power must be exercised under the Constitution and is vested in different functionaries such as the President through the Cabinet for the executive,[5] the legislature;[6] and in the courts.[7] The Constitution sets the normative benchmark for the practice of constitutional democracy in Zimbabwe. Constitutional democracy is also underscored in the constitutional supremacy clause which makes the Zimbabwean Constitution the supreme law of the land. Any practice, law, custom or conduct must be consistent with the Constitution otherwise it would be invalid to the extent of its inconsistency.[8] Constitutional sovereignty in Zimbabwe, however, compares with other forms of sovereignty such as popular sovereignty (through the ‘we the people’ clause), legislative sovereignty, the courts’ legal sovereignty, state sovereignty, and presidential sovereignty.[9] Although it is a unitary, democratic sovereign republic, Zimbabwe also possesses qualities of constitutional federalism especially relating to the devolution of powers.[10]

Constitutionally, Zimbabwe has a tier system of government. The tiers of government include the national government, provincial and metropolitan councils and local authorities (rural and urban).[11] The power structure in Zimbabwe is as follows: The President and the Vice Presidents are directly elected jointly by registered voters throughout Zimbabwe.[12] The Executive comprises the President, Vice Presidents, Ministers,[13] Cabinet[14], and the Attorney General.[15] There are two houses of Parliament which are the Senate and the National Assembly.[16] Senators are elected from provinces,[17] provincial assembly of chiefs[18] and in terms of the Electoral Laws to represent persons with disabilities.[19] People elect representatives to the Zimbabwean National Assembly and local government. Members of the National Assembly are elected from the two hundred and ten constituencies into which Zimbabwe is divided through a secret ballot.[20] An additional sixty women, six from each province, are elected under a party-list system of proportional representation.[21] Although the legislature has law-making functions, the Government through Cabinet can also prepare, initiate and implement national legislation.[22] The powers are however exercised subject to the Constitution.[23]

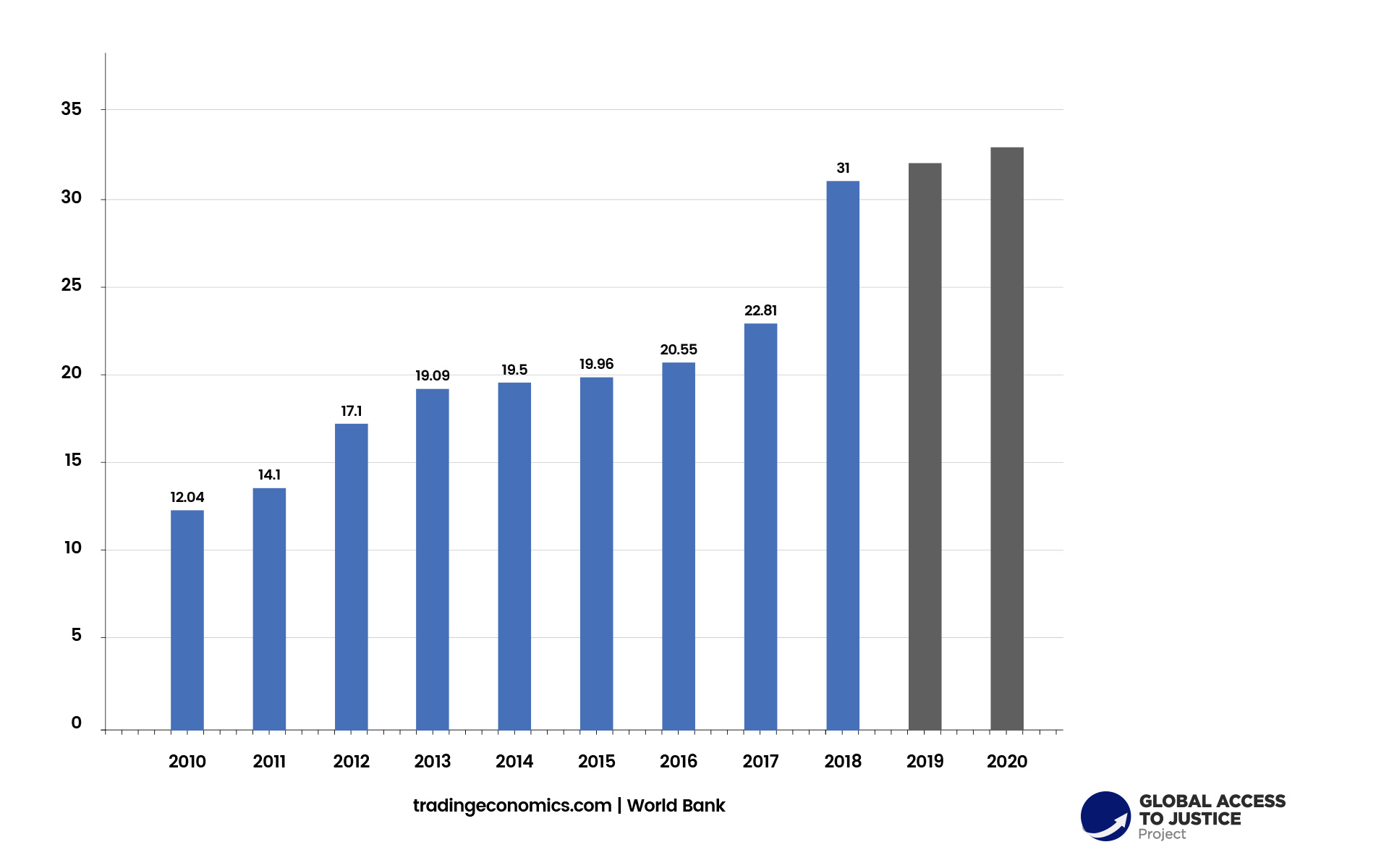

In terms of the social development of its people and commitment to social protection services, the ZUNDAF Report shows that there are approximately 3 million households in Zimbabwe, and of these, about 1.1 million are not poor, 1.4 million are moderately poor and 500,000 are extremely poor.[24] The UN Human Development Report shows that Zimbabwe is part of medium human development countries with a Human Development Index score value of 0.563, which places the country at number 150 on a worldwide ranking.[25] The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Zimbabwe was worth 31 billion US dollars in 2018, in which the GDP value of Zimbabwe represented 0.05 percent of the world economy.[26] The diagram below shows the GDP trends from 2010 to 2020. In essence, the GDP between 2018 and 2020 did not record any significant differences even though Zimbabwe changed currency reporting from United States dollars to RTGS dollars.

Chart 01. Zimbabwe GDP

Source: tradingeconomics.com | World Bank

Source: tradingeconomics.com | World Bank

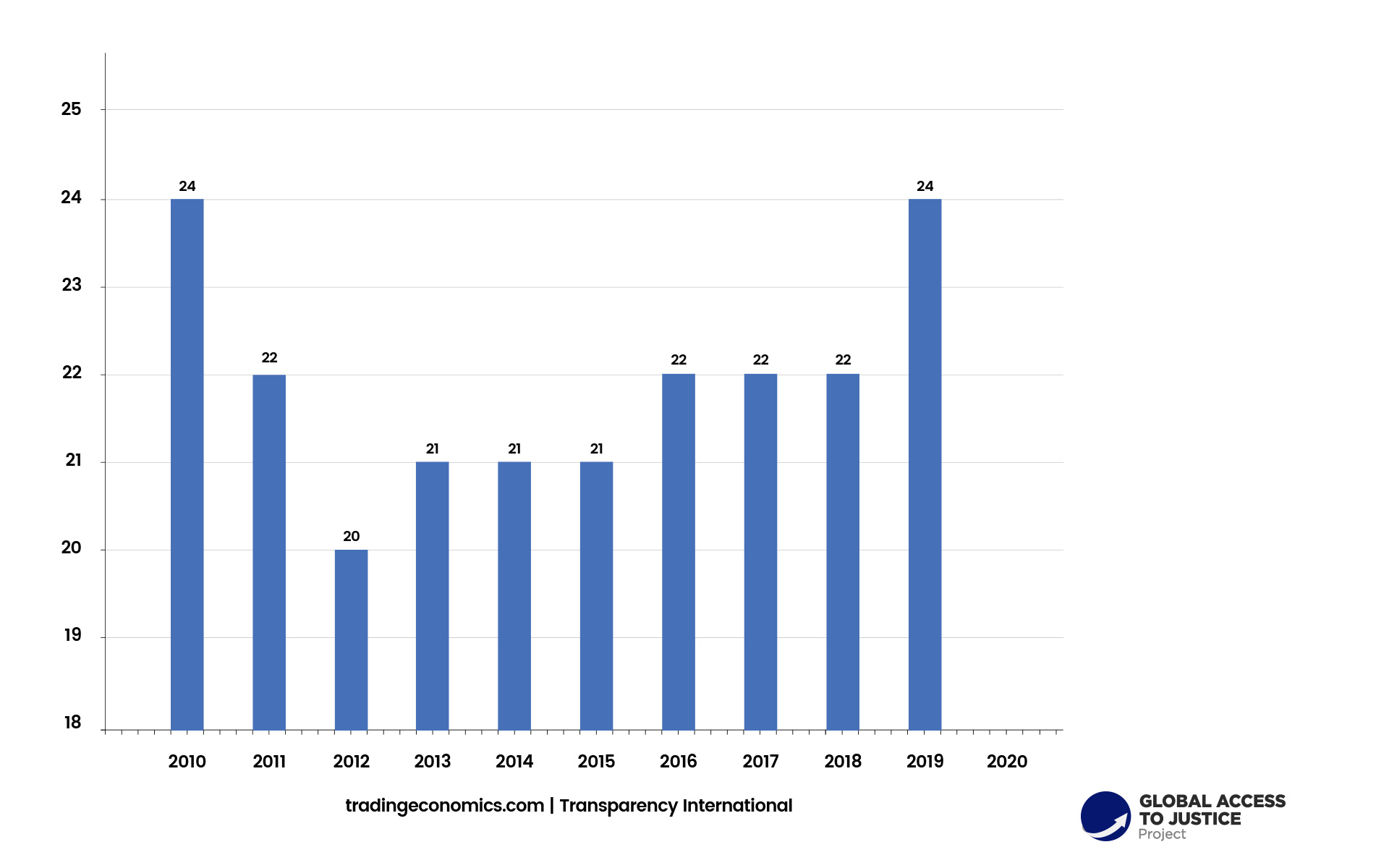

While the corruption perception index for Zimbabwe remained at 22 in 2017 and 2018, below the regional average for Sub-Saharan Africa which is 32, Zimbabwe remains one of the countries perceived to be corrupt.[27] Generally, the score of 24 in 2019 is based on the CPI trends from 2010 shown in the diagram below.[28] Zimbabwe is the 158 least corrupt country out of 180 countries ranked by Transparency International.[29]

Chart 02. Corruption perception index

Source: tradingeconomics.com | Transparency International

Source: tradingeconomics.com | Transparency International

Zimbabwe however recorded, despite economic challenges, significant improvements in realizing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in reducing HIV prevalence, gender equality, education, tertiary enrolments, maternal health, and information communication technology.[30] Zimbabwe has also committed to ensuring the realization of the global goals, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are a call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030.[31] It remains to be seen if the SDGs will be realised considering the fact that Zimbabwe still has a growing problem of people who are living in low-income households. The Total Consumption Poverty Line (TCPL) for an average of five persons per household stood at $873.00 in March 2019.[32] Against the poverty and other challenges, Zimbabwe is poised to attain the status of a middle-income country (MIC) by 2030.[33] MICs are defined by the World Bank as having a per capita gross national income between $1,026 and $12,475.[34] Currently, Zimbabwe is classified as a low-income country, and in 2016, Zimbabwe had a per capita gross national income of $890.[35] Apart from the national vision to achieve MIC status by 2030, Zimbabwe has also shown a commitment to the continental vision, Africa’s Agenda 2063. The Continental vision seeks to categorize the SDGs into clusters under the Five Ps – People, Prosperity, Planet, Peace, and Partnerships.[36]

With Zimbabwe’s current economic vision emphasizing on ‘economics over politics,’ ‘ease of doing business,’ and the mantra ‘Zimbabwe is open for business,’ Zimbabwe needs to improve on winning investor confidence if it is to get the much-needed foreign direct investment (FDI). While FDI is important, Zimbabwe also needs to support the local small and medium companies (SMEs) as well as big companies especially through easing the ways that enable the companies to access foreign currency.[37] This will ensure that eighty percent of the business that is operating informally are encouraged to formalize their operations. This, in turn, contributes to the improvement of the GDP per capita. Cumulatively this improves the people’s standards of living and will demonstrate the government’s commitment to formulating and implementing policies that are aimed at promoting social progress. As will be shown later in this report, Zimbabwe’s commitment to upholding the rule of law, adherence to constitutionalism and commitment to the principles of good governance espoused by the Constitution must play a significant role in promoting access to justice for all Zimbabweans. Further, the commitment to human security which was emphasized during the military-assisted transition’s Operation Restore Legacy in 2017 created the fervent expectation that the economy and politics of Zimbabwe would be improved significantly. This was based on the concept of popular constitutionalism which united Zimbabweans to celebrate a transitional moment from together. While the Government of Zimbabwe’s (GoZ’s) current political trajectory places economics over politics, there is an urgent need to demonstrate in earnest that there is political resolve to end the economic meltdown which has created uncertainty for the generality of the populace. Specifically, the Government’s move away from a multicurrency regime to a single currency regime saw many people losing their savings and investments that they had made in United States Dollars. There was no smooth transition from a dollarized economy to the introduction of RTGS dollars, whose rates continue to fluctuate by the day much to the detriment of citizens and businesses. This has also impacted on national and private audit reportage. Specifically, the Auditor General’s report indicates that 80% of the audit report is based on issues relating to governance.[38] The current Supreme Court judgment which affirmed the position that assets and liabilities, including judgment debts, denominated in United States Dollars before the effective date of 22 February 2019, shall on, or after the effective date is paid in RTGS dollars on a one-to-one rate also adds to the problems that are being faced by business and citizens.[39] The judgment largely cuts investor confidence as there is a need for both legal and financial certainty, especially where citizens and businesses fail to access their financial capital because of harsh policy and legislative changes.[40] Effectively, linked to legal certainty is the need for the GoZ to respect vertical accountability or vertical application of the Constitution to the people of Zimbabwe, as the repositories of state power.

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of Legal System

A legal system is defined as the total of the law of a given society and includes the way(s) it is made, how it is enforced and the institutions involved in its making and enforcement.[1] Generally, legal systems are classified as common law or civil law, depending on the extent to which case law (judicial precedent) and statutory-based law are used in a country. Practically speaking though, the distinction between English or Anglicised common law and French Civil law is blurred by the argument that the French and English lived under ‘common law,’ with the Anglo-Norman common law being part of the French feudal world.[2] The distinction is also explained by variations in the usage of the term common law in three ways that include firstly, the law that applies to all people in a society, regardless of race, tribe or sex.[3] Secondly, it is used to denote a classification of legal systems that have the influence of English common law as distinct from those with a Roman law basis.[4] Thirdly, it refers to that portion of the law that is not derived from statutes but is developed from the principles made by judges in the course judicial review.[5] The Zimbabwean legal system, though largely considered a common law system also enjoys the benefits of civil law jurisdictions such as the codification of many criminal laws under the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act.[6]

Zimbabwe’s Constitution does not have a provision that limits the application of the Roman-Dutch-cum-anglicised common law, to the law that was commonly administered at the Cape of Good Hope as of 10 June 1889.[7] Further, the Constitution does not only emphasize the importance of the common law but also places due regard on the influence of customary law and the role of the judiciary in developing both common law and customary law.[8] The mixture of statutory and case law, the inherent power of the superior courts to protect and regulate their process, the inherent power to develop the common law or customary law, taking into account the interests of justice and the provisions of the Constitution, features beyond strict common law legal systems.[9] Concerning the usage of Roman, Roman-Dutch, English and Zimbabwenized concepts, the legal system of Zimbabwe seems more of an a la carte system than either strictly common law or hybridized. Litigants choose what they want from separate systems depending on the lacuna they want to fill in. the absence of a well-developed set of common law or codified civil laws means that litigants and their legal representatives have to occasionally assist the courts with specific research on the area of concern from various legal systems. Further, the Zimbabwean legal system is also based on a separation of both political function and separation of political power since the separation of powers is an entrenched founding value and principle of good governance.[10] While detail may not be given in this report on the whole of the law of Zimbabwe, it suffices to note that the areas of law in Zimbabwe are broadly classified either as public or private law as was the case in the Roman legal tradition. The major disciplines of public law in Zimbabwe include constitutional law, administrative law, public international law and human rights. The major disciplines of private law include contract, insurance, family, succession and so forth.[11] There is also a classification of Zimbabwean laws into procedural laws especially in areas relating to the criminal and civil procedure as well as aspects relating to conveyancing and notarial work. Both the civil and criminal laws in Zimbabwe point to the use of an adversarial form of dispute resolution. While most areas of the law are largely based on accusatorial or adversarial procedure, some laws such as those on child and spousal maintenance are usually resolved through inquisitorial procedure since the judicial officer takes the role of a maintenance officer and has to actively determine what is to be considered in the best interests of the child or fair to the spouses concerned.[12]

2.2. The Zimbabwean Justice System

Apart from the constitutional doctrine of separation of powers referred in sections 1 and 2.1 above, the Constitution imposes obligations that are binding on every person, natural or juristic, including the State and all executive, legislative and judicial institutions and agencies of government at every level.[13] The State is obligated to take all practical measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to provide legal representation in civil and criminal cases for people who need it and are unable to afford legal practitioners of their choice.[14] The equality and non-discrimination constitutional provision enjoins the State to ensure that all persons are equal before the law and have the right to equal protection and benefit from the law.[15] In terms of administration of justice, the Constitution provides that every person has a right to administrative conduct that is lawful, prompt, efficient, reasonable, proportionate, impartial and substantively and procedurally fair.[16] Linked to this is the provision which relates to fair hearing through a fair and public trial within a reasonable time before an independent and impartial court.[17] The Constitution also provides that the courts are independent and are subject only to the Constitution and the law, which they must apply impartially, expeditiously and without fear, favor or prejudice.[18] The independence, impartiality, and effectiveness of the courts are fundamental to the rule of law and democratic governance in Zimbabwe.[19] The Constitution thus provides explicitly that neither the State nor any institutions or agency of government at any level, and no other person, may interfere with the functioning of the courts.[20] Orders or decisions of the Court bind the State and all persons and governmental agencies to which it applies, and must be obeyed by them.[21] Linked to the independence and effectiveness of courts is the need for courts to observe principles that guide the judiciary such as doing justice to all, irrespective of status; not delaying justice, and considering the courts’ role as paramount in safeguarding human rights and freedom and the rule of law.[22]

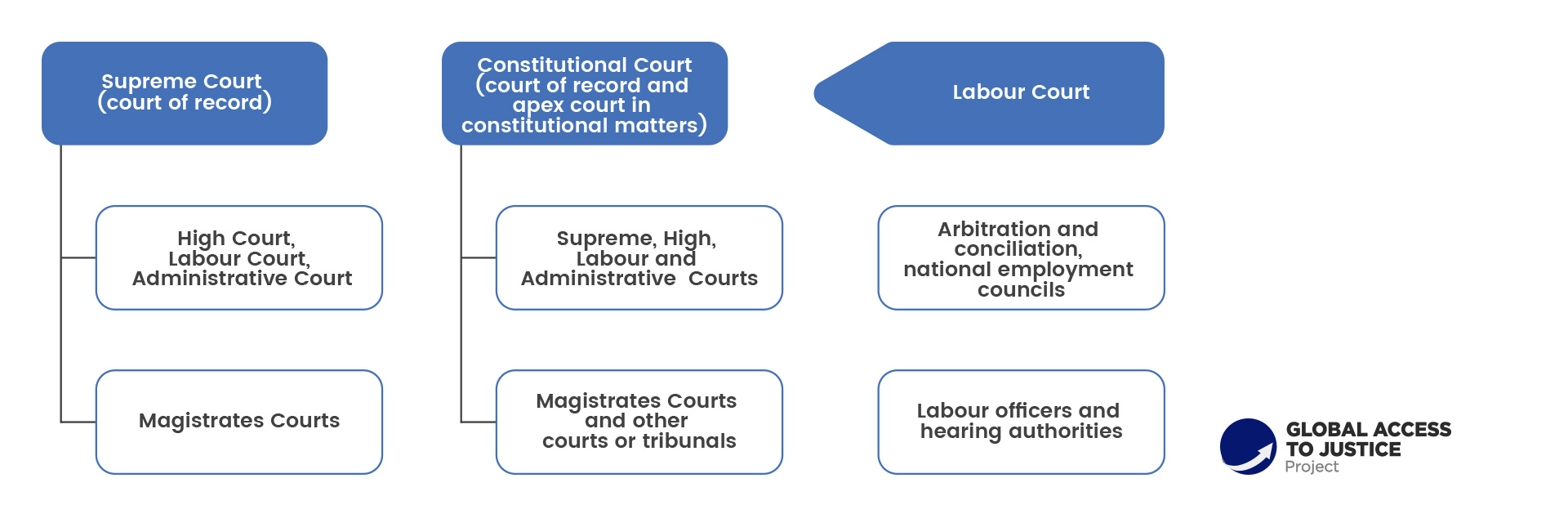

The courts fall under different types: Superior courts of record, which include the Constitutional Court,[23] Supreme Court[24] , and High Court;[25] relatively superior courts of record or first instance, namely, Administrative Court[26] and Labour Court;[27] and other courts and tribunals of record such as magistrates’ courts, customary law courts, courts subordinate to the High Court and tribunals for arbitration, mediation and other forms of alternative dispute resolution.[28] There is a move to decentralize the High Courts in Zimbabwe. Currently, there are High Courts in Harare, Bulawayo, Mutare, and Masvingo. The specialized courts that fall under the High Court include the Fiscal Court. Other specialised courts include the Commercial Court and Corruption Courts which are also found under the magistrates’ courts hierarchy. Other courts include the small claims court and the children’s court. Courts such as the Labour Courtexercise special jurisdiction on matters that do not emanate from the magistrates courts. The Labour Court is normally the court of the first instance as well as the appellate court in cases regarding employers and employee organizations with the Superior Courts having no exclusive jurisdiction over its decisions. The cases emanate from conciliation or arbitration proceedings. The Administrative Court is a special court which serves as a court of record and first instance but can also deal with appeals and reviews from decisions of rent boards or local authorities, especially in issues relating to town planning, servitudes and so forth.

2.2.1. General on Courts

In general, the court system in civil and criminal matters usually include the Magistrates’ court as the court of the first instance, the High Court and the Supreme Court as the court of the last instance in non-constitutional matters. The Constitutional Court is the apex court in constitutional matters. On details of various courts and matters appertaining, the Judicial Services Commission has a website where various courts are listed.[29] The current changes involving corruption courts and commercial courts can be represented in the table below.

| Project | Status |

| Construction of an Anti-Corruption Court in Gweru | Complete |

| Construction of an Anti-Corruption Court in Masvingo | Complete |

| Construction of an Anti-Corruption Court in Mutare | Complete |

| Construction of Mount Darwin Magistrate Court | Work in Progress |

| Commercial Court at Bristol House-Harare | Work in Progress |

| Construction of Chinhoyi Magistrate Court | Work in Progress |

| Refurbishment of Hwange Magistrate Court | Work in Progress |

| Refurbishment of Mbare Magistrate Court | Work in Progress |

| Plans are underway for the construction of a new Kwekwe Magistrate Court | Work in Progress |

| The JSC bought new Offices for the Master of High Court in Bulawayo. | Work in progress |

| Construction of Lupane Magistrates Court. | Work in progress |

| Construction of Gwanda Magistrates Court. | Work in progress |

Source: JSC website.

2.2.2. Courts of record and superior Courts

The administrative court has jurisdiction over administrative matters as may be conferred upon it by an Act of Parliament.[30] There is currently a single Administrative Court which is based at the Harare High Court. The Constitutional Court is the highest Court in constitutional matters and its decisions on those matters bind all other courts.[31] The Supreme Court is the final appeal court for Zimbabwe, except in matters over which the Constitutional Court has jurisdiction.[32] The registrar of the Supreme Court may be given powers through rules of the court to make orders in uncontested cases other than those affecting status or custody or guardianship of children.[33] The registrar of the Supreme Court can also be given powers to decide preliminary or interlocutory matters, including applications for directions, but not matters affecting the liberty of any person.[34] The Constitution provides that the rules that confer powers on the Supreme Court registrar to give persons adversely affected the right to have the decision reviewed by a judge of the Supreme Court.[35] The judge may confirm the decision, amend it or set it aside or give any other order or decision he or she thinks fit.[36] The High Court has original jurisdiction in all civil and criminal matters; can supervise magistrates courts and other subordinate courts and review their decisions; may also decide constitutional matters except those only the Constitutional Court can decide and has appellate jurisdiction as may be conferred by Statute.[37] The Constitutional Court has been criticized for relying heavily on avoidance and subsidiarity doctrines which clog the court with cases resolved on technicalities.[38] The superior courts, the Constitutional, Supreme and High Court have also been criticized for failing in some instances to protect women who do their work as human rights defenders.[39] Other instances that raise concern include practice directions that set prohibitive costs for electoral disputants,[40] delays by the Constitutional Court to confirm constitutional orders of invalidity from the High Court and delays in passing judgments.[41]

The Superior courts have however been making progressive judgments relating to various generations of human rights protected under the Declaration of Human Rights or which can be read into the Declaration of Human Rights. The rights include right to privacy;[42] the need to bring to court arrested individuals within forty-eight hours;[43] the political rights;[44] women’s rights;[45] right to administrative justice;[46] internet freedom[47] and right to liberty. The superior courts also issued judgments that protect lawyers who are arrested in the course of their duties[48] and also allowed amicus curiae to intervene in cases that threatened the independence of the judiciary in as far as the appointment of the Chief Justice is concerned.[49]

2.2.3 The Court Systems in Zimbabwe

The diagram below simplifies the structure of the courts in Zimbabwe. Litigants can start file cases in the magistrates’ courts and access the High Court and Supreme Court in ordinary civil and criminal matters. They may also start in the magistrates’ court and go all the way to the Constitutional Court in constitutional matters. In labor issues, litigants may start from hearing authorities at their workplaces, through the conciliation, the Labour Court and then to the Supreme Court or Constitutional Court.

2.3. Informal Justice Structures

2.3. Informal Justice Structures

There are different informal justice systems in Zimbabwe such as arbitration tribunals, labor-related conciliation forums, Small Claims Court, Customary Law Courts, and Maintenance Courts. These courts or tribunals use formal but unofficial structures of evidentiary presentation and for related dispute resolution. For instance, the customary courts use their own local rules and other forms of interactive alternative dispute resolution for resolving issues concerning customary disputes. Villagers can participate in the proceedings by asking questions without following the formal presentation of opening a case for the state of the private party, subjecting the other party to cross-examination and so forth. In inquest proceedings, members of the public can again ask questions flexibly and the judicial person presiding over the inquest records the questions. Maintenance cases can be done in public or private depending on the best interests of the child. However, customary law courts are recognized by the Constitution as legal structures.[50] Customary law courts vary across the ten provinces and many districts in Zimbabwe. Litigants who are not pleased with the findings of customary courts can also appeal to the magistrates’ courts or can raise constitutional issues as contemplated by section 2 of the Constitution that laws, practices, customs, or conduct inconsistent with the Constitution are void to the extent of their inconsistency.[51] The informal justice systems in Zimbabwe are an important legal tool to reduce backlogs in the formal courts and also help in ensuring that various traditional societies across the ten provinces and many districts in Zimbabwe can localize the usage of their traditional mechanisms of resolving disputes. As far as access to justice in informal justice systems is concerned, lawyers usually do not represent clients in the small claims court. Lawyers and non-lawyers, especially members of the workers’ committee, may represent employees in arbitration or conciliation proceedings. Customary Law Courts are however frequently criticized for their many penal requirements such as forcing litigants to pay using beasts or forcing litigants to travel long distances to follow the complainant in a specific case.

2.4. The Structure of the Legal Profession

The law society of Zimbabwe’s website shows that there are thousands of practicing lawyers.[52] It may be important to capture the actual number of registered lawyers.[53] Legal practitioners or lawyers have to be formally trained at a University which offers LLBS degree at the undergraduate level. The local universities include the University of Zimbabwe, Midlands State University, Zimbabwe Ezekiel Guti University, and Great Zimbabwe.[54] There were 44 deregistered lawyers from 1997 to 2019.[55] However, most practicing lawyers also acquired their law degree outside Zimbabwe in countries such as South Africa and the United Kingdom.[56] A fused legal profession exists in Zimbabwe and there is no distinction between solicitors and advocates unlike the situation in other common law jurisdictions. The Law Society of Zimbabwe (LSZ), through the secretariat, is the licensing authority for lawyers. It also administers licenses for inhouse counsel, lawyers in non-governmental organizations, lawyers in commerce, and those in private practice.[57] For a lawyer to practice as a licensed attorney, they have to complete a four-year or five-year law degree and be in good standing with the LSZ; demonstrate evidence of continuous professional development for those lawyers who would have completed their pupillage; continuous pupillage training for lawyers undergoing pupillage training; contribute to the Law Society compensation fund, and adhere to the legal code of ethics for lawyers.[58] Lawyers who are in private practice and run law firms and ‘advocates’ who run de facto bars can use the titles advocate or barrister without event. The law does not require certain legal practitioners and legal advisors to be licensed attorneys, including company secretaries, legal aid societies, law officers in government institutions, judges, trustees, estate agents, paralegals, and debt collectors.

Judges are lawyers drawn from private practice, de facto advocates chambers, the prosecution, the judiciary, commerce and other common law jurisdictions. They however but do not necessarily renew their licenses with the LSZ. Some magistrates and prosecutors do not possess degrees as they were trained at the Judicial College of Zimbabwe or staff colleges. The relationship between the bench (judiciary) and the legal profession should be warm and based on mutual respect.[59] In terms of licensing other organizations other than law firms, law-based organizations which do not run law firms usually operate under partial practicing certificates since they do not administer trust funds and mainly rely on donor funds.[60] The law-based NGOs that work with and have lawyers who are licensed under the LSZ normally provide legal advice on specific rights issues. For example, ZELA deals with collective rights relating to the environment; ZWLA and WILSA deal mainly with women’s rights and other legal issues; ZLHR, NGO Forum, Zimrights deal with a broad range of human rights; and JCT deals mainly with children’s rights. The executive secretary of the LSZ is the issuing authority when it comes to practicing licenses. Other important institutions under the LSZ include the Council for Legal Education and Law Society Tribunal. The law society also works with Universities, institutes, courts, and the public. Critically, the LSZ’s motto is ‘committed to justice and the rule of law.’ It partners key institutions in fighting corruption under the ‘Against corruption together’ (ACT). In this endeavor, the law society does not tolerate instances of corruption from lawyers but usually enjoins other actors to be truthful when dealing with allegations or investigations on corrupt members of the legal profession.[61] There are non-university institutions that offer legal training such as Zimbabwe Institute for Legal Studies.[62] The Judicial College of Zimbabwe also trains magistrates in partnership with the legal profession and other stakeholders on various issues including judicial integrity.[63] In essence, legally trained prosecutors,[64] law officers in state institutions, lawyers in commerce, NGOs, at de facto bars or those in private practice and those in the judiciary must all adhere to legal ethics. This is the position for prosecutors, magistrates and judgesd who are registered with the LSZ. The position is important even though prosecutors and judges have their institutional codes of conduct. There have been concerns to ensure effective litigation in superior courts through allocating specific time for arguments at the Supreme Court. Other judges, including the late Chief Justice Godfrey Chidyausiku, preferred to separate solicitors and advocates, with advocates enjoying the right of audience in superior courts. Regional and international legal bodies that also influence lawyers in Zimbabwe include the International Bar Association (IBA) and the SADC Lawyers Association (SADC-LA).

The number of lawyers in Zimbabwe is increasing due to the training of Zimbabwean students mainly in South Africa; the increase in law schools in Zimbabwe as well as a move by Faculties of law to offer both conventional and part-time law training at universities such as the University of Zimbabwe. Although lawyers who are trained outside Zimbabwe are required to write conversion examinations, similar to articles or admission examinations in other jurisdictions, before they can practice in private practice, they are normally allowed to enter the job market in other public sectors such as prosecution and magistracy or private sector as legal advisors and company secretaries without restriction. The number of lawyers getting training in winter and summer schools, CPD courses organized by the LSZ and other international courses has increased. Thus, a higher number of lawyers are also advancing their studies beyond the undergraduate degree. However, concern has been raised that the female lawyers usually leave private practice for reasons not yet determined through empirical studies. Concern has also been raised that judges of the Superior Courts seem to treat advocates running de facto advocates bars to lawyers from private law firms. Concern also rises from bogus or briefcase lawyers who not only are unregistered but also tout for clients usually using names of reputable lawyers. An increasing number of lawyers are also appearing at the disciplinary tribunal for cases ranging from misappropriation of trust funds to poor case management or failure to properly advise clients. The LSZ has been carrying out spot checks to see if members comply with the LSZ requirements. In some cases, members have been dismembered or forced to undergo pupillage training.

2.4.1. Legal representation in Zimbabwe

The Constitution shows that legal representation can be done by self-actors, lawyers of their choice or provided by the state,[65] and various categories of people, including people with the necessary expertise.[66] Those who can represent holders of constitutional rights include those acting on behalf of others who are incapacitated, those acting in the public interest, and those acting in the interests of a class or group of persons.[67] The national objectives show that there is a need for legal aid to ensure legal representation in civil and criminal cases for people who need it and are unable to afford legal practitioners of their choice.[68] Those who do not afford lawyers can also be represented by law officers from the legal aid directorate; by pro-bono organizations (including mainly the law-based organizations listed in section 2.4), pro-deo and in forma pauperis lawyers (these shall be dealt with under the specific titles later). Those who can get representation from private lawyers usually do so in civil and criminal cases. For criminal cases, private lawyers can enable accused persons to assert their rights as arrested and detained persons[69] or rights as accused persons.[70] When a criminal suspect is arrested, the Constitution provides that they must be permitted, without delay, at the expense of the State, to contact their spouse or partner, or a relative or legal practitioner, or anyone else of their choice.[71] They can on their expense request for the service of a private legal practitioner and a medical practitioner of their own choice.[72] They must be released unconditionally or on reasonable conditions, pending a charge or trial, unless compelling reasons are justifying their continued detention.[73] Detained persons, including sentenced prisoners, have the right, at their own expense, to consult in private with a legal practitioner of their choice, and to be informed of this right promptly.[74]They also have the right to communicate with and be visited by spouses or partners, relatives, chosen religious counselors, chosen legal practitioners, chosen medical practitioner and anyone of their choice.[75] In asserting their rights as accused persons, such persons must be presumed innocent until proved guilty;[76] must be represented by legal practitioners of their choice;[77] and by a legal practitioner assigned by the State at the state’s expense if substantial injustice will result.[78]

2.4.2. Judges in Zimbabwe

Judges in Zimbabwe are appointed by the President. The chief justice is head of the judiciary and is in charge of the supreme and constitutional court.[79] The judges of the superior courts, that is, the high, supreme and constitutional courts must develop the common law and supreme law of Zimbabwe.[80] A person qualifies for appointment as a judge if he or she is at least 40 years and has a sound knowledge of constitutional law.[81] Besides, they must either have practiced as a judge in a Roman-Dutch or English common law jurisdiction where English is recognized as an official language[82] or have for at least 12 years, whether continuously or not, have been qualified to practice as a legal practitioner in Zimbabwe or a country in which the common law is Roman-Dutch or English and English is an officially recognized language.[83] The Constitution enjoins the judiciary to be independent.[84]

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

In Zimbabwe, public prosecution falls under the authority of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) which is an independent civilian institution.[1] Private prosecutors are however allowed in instances where the NPA declines prosecution. In criminal cases, the complainant makes a formal complaint at the charge office at a police station. The police record the complaint in a report received book (RRB) or occurrence book (OB). The complainant is given an RRB or OB reference. When the accused person is subsequently arrested a station reference (CR) is given indicating the name of the police station. The arresting detail is required to read the accused person his or her rights including the reason for the arrest; right to remain silent and the consequences thereof and right to a lawyer.[2] An accused can be arrested with or without a warrant depending on the nature of the offence. A person who is arrested and detained to go to court should be taken to the court before the expiry of 48 hours.[3] On initial appearance, the accused person first goes to the prosecution office where his case is vetted. The complainant and accused person being interviewed. Those accused who are brought on Form 242, where the State has not finished investigations, may be referred to a remand court. The prosecution can decline prosecution or give some direction to the police on how best to proceed.

Where the prosecution decides to prosecute the accused person, the case is referred to as a remand court; a trial court for the issuance of a trial date or a fast track court. The fast track court process is usually used in instances where the case involves a single witness and the accused is prepared for trial. In most cases, a represented accused person usually refuses to proceed and asserts his or her right to a fair trial and the right to be given adequate preparation to prepare for his or her defence.[4] Where the accused person appears either in a remand court or trial court depending on whether the police would have finished investigations, the accused can in both instances challenge the lawfulness of his or her arrest or placement on initial remand. Normally at busy courts such as the Harare Magistrates Courts or Rotten Row courts, the magistrate may reserve a ruling to another date and the accused may be remanded in custody pending the ruling. Under such instances, the application challenging placement on remand is not accompanied by the duty of the judicial officer to promptly dispense justice.[5] In instances where a challenge to placement on remand is not made or is dismissed, the accused can proceed to indicate that he needs to be admitted to bail. The State or prosecuting authority bears the onus as the dominus litis to show compelling reasons why the accused person has to be denied bail pending trial.[6] Where bail is granted, the accused is normally given time to file his or her defence outline. The matter is postponed at the instance of the court, state or accused person and a trial date are given. Where an accused is admitted to bail in a remand court, they are usually asked to come back at the next remand date or are referred to a trial date. Where the accused subsequently attends a remand court on many occasions without being given a trial date, he or she can challenge further remand by applying for further remand to be refused (FRR). The court can grant the application or reject it in the interests of justice.

The trial commences with the State leading evidence from the complainant who is then subjected to cross-examination by the accused person. The State calls its witnesses and closes its case. The accused person has an option to apply for discharge at the close of the State’s case on the basis that no evidence would have been presented to empower a case to convict the accused. The court as the case and court manager can refuse to discharge the accused and will put accused to his defence. The accused can proceed to the defence case or can apply for review to a higher court. Such an application is normally accompanied by an application for the recusal of the magistrate on the basis that he or she is biased. Courts do not take applications for recusal lightly since the presiding court is best placed to assess evidence than a court sitting elsewhere. If the application for discharge is granted, the accused is acquitted and a verdict of not guilty and acquitted is entered. If the accused proceeds to defence case, he or she opens the defence case and is cross-examined. The same happens with his witnesses. When the accused closes his case, the parties file closing submissions. The court then passes its judgment and the accused can be acquitted or convicted. The conviction of an accused person can also be based on a guilty plea. After being found guilty as charged or as pleaded, the accused person is allowed to make a plea in mitigation. The State is asked to show aggravating circumstances for sentencing. The court then weighs the mitigating factors and aggravating factors before imposing a sentence.

It takes into consideration aggravating factors such as the seriousness of the offence, mandatory sentences, high moral blameworthiness; recidivism and so forth. In some instances, the accused person can be sentenced to a custodial sentence or non-custodial sentence such as community service, fines or being warned, cautioned and discharged. The Constitution also allows applications for those detained illegally or whose whereabouts are not known to be represented by any person in the High Court for an order of habeas corpus requiring the detained person to be released or brought to court for the lawfulness of the detention to be justified or whereabouts to be disclosed.[7] Accused persons who are convicted in magistrates courts file their appeals at the High Court. A notice of appeal is processed at the High Court registry if it has been noted with the clerk of court at the trial court.[8] After processing the appeal, the clerk of the court is obligated to prepare and lodge the appeal records with the High Court.[9]

3.1.1. The Criminal Investigation Process

The criminal investigation is done by the members of the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP). The ZRP is a security institution[10] whose investigative functions include the detection and prevention of crimes. Members of the ZRP must not act in a partisan manner; further interests of any political party; prejudice lawful interests of any political party or cause, or violate fundamental rights or freedoms of any person.[11] The members are subject to the authority of the Constitution, the President, and Cabinet and are also subject to parliamentary oversight.[12] The ZRP members can be assisted by arresting details from the various peace officers who include prison officers, magistrates, judges or members of the Zimbabwe Anti-corruption Commission (ZACC). The golden rule of effective investigations is that the ZRP must avoid arresting suspects to investigate cases but should investigate the offences before arresting suspects. The Constitution empowers the ZRP to exercise its functions in cooperation with the intelligence services;[13] bodies established by law[14] and regional and international bodies formed to combat crime.[15]

3.1.2. Critiques of the Criminal Investigation Process

Critical concerns normally include the arrest of lawyers in the course of defending their clients; the incidents where police arrest to investigate; the arrest of political opponents through dragnet arrests; the involvement of prosecutors from the security services, and the failure to observe due process of the law. The latter occurs where suspects are normally brought to court after the expiry of forty-eight hours; assault of suspects in police custody; death in police custody; and unauthorized seizures of property. Sometimes the police dispose of exhibits before the trial is completed and this affects the conducting of trial.

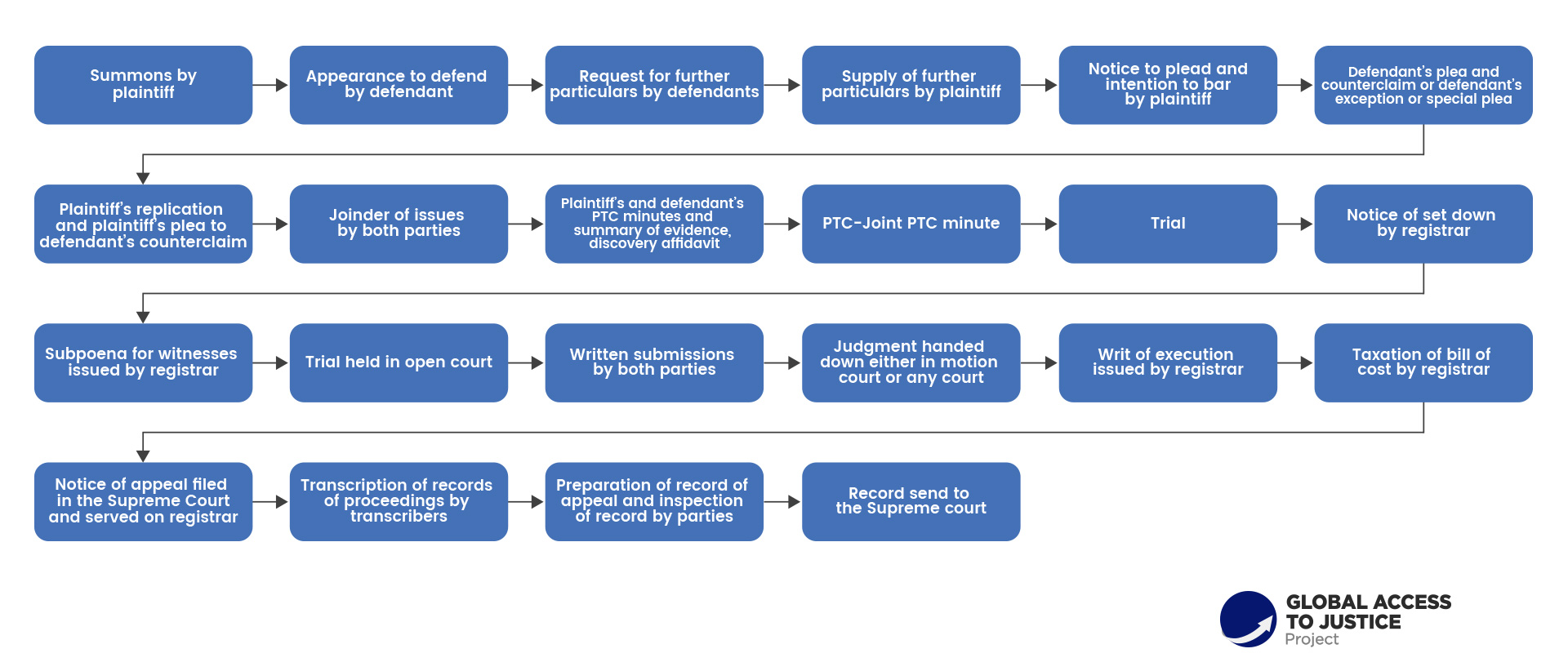

3.2. Civil Procedure

Civil cases begin either as action proceedings or application proceedings. In both Magistrates Courts and the High Court, action proceedings commence formally with the issuance of summons by the plaintiff. Sometimes a letter of demand is issued. Although it is not necessary to threaten legal action in a letter of demand lawyers normally do so. The summons is followed by the entrance of appearance to defend by the defendant in instances where they intend to oppose the plaintiff’s claim. The defendant can either except to the summons, request for further particulars to the summons or file a plea denying specific claims in the summons or confessing and avoiding certain claims. In the plea, the defendant can file a counterclaim and the plaintiff is required to request further particulars and plead to the counterclaim. Failure to file a plea in time may be followed by a notice to plead and intention to bar. The filing of a plea is followed by replication; then summary of evidence; draft Pre-trial Conference (PTC) minutes; closure of pleadings, discovery of evidence; application for PTC; meeting of parties before the PTC at the instance of the judge’s or magistrate’s direction; the holding of the PTC; filing of joint PTC minute; and application for trial if parties fail to settle. During the trial, the parties give opening addresses and the plaintiff opens his or her case and is cross-examined. The same procedure happens with the plaintiff’s witnesses. After the close of the plaintiff’s case; the defendant can apply for absolution from the instance which is similar to the application for discharge in criminal cases. If the application is dismissed by the court, the defendant opens his case and is also cross-examined. When both parties have closed their cases; they file closing submissions. The court then issues a judgment and parties can appeal or seek a review from a superior court.

In application proceedings, the applicant, intervenor, amicus curiae or petitioner in some instances applies with a founding affidavit setting out concisely the basis of the claim and whether the applicant can sue and the defendant can be suited. The Applicant normally falls or rises on his or her affidavit and is obligated to exercise due care when drafting the founding affidavit. The application should be accompanied by a draft order setting concisely the nature of the relief sought. In interlocutory applications such as applications for a provisional order; the relief in the provisional order must be different from the one sought in the final order. Other applications are ordinary court applications whereas others are urgent or ex parte depending on the court of choice. Certain forms are mandatory and a matter may be dismissed, struck off the roll or removed from the roll of cases for want of compliance with certain forms and rules. The Respondent is enjoined to file a notice of opposition and opposing affidavit to the application. He or she can also file a counter application and the applicant is also obligated to respond to the counter application. The plaintiff can then file an answering affidavit to the opposing affidavit. The parties then file heads of argument stating the factual basis and the law supporting their cases. The plaintiff or defendant can apply for the setting down of the matter. The defendant may move to have the plaintiff’s case dismissed for want of prosecution or compliance with court rules. The Plaintiff can also move to have default judgment granted in instances where the defendant fails to comply with rules relating to the filing of documents. After the setting down of the matter, the parties go for the hearing of their case. The applicant presents his case first and the respondent responds. Sometimes judges raise technical arguments before either party has addressed them and the matter may be struck off, removed from the roll or withdrawn depending on the nature of the query raised by the judge. For divorces, matters that are not opposed are usually referred to as the unopposed roll. In other cases, matters that are not opposed are referred to as the unopposed roll. Unopposed matters may also be referred to as a magistrate’s or judge’s chambers through a chamber application. Where a chamber application is opposed, judges at the High Court are divided on whether it is automatic that the matter has to be referred to the opposed roll. Barring concessions or other approaches by the parties, the High Court civil action stages can be shown below in general:[16]

Chart 03. High Court civil action stages

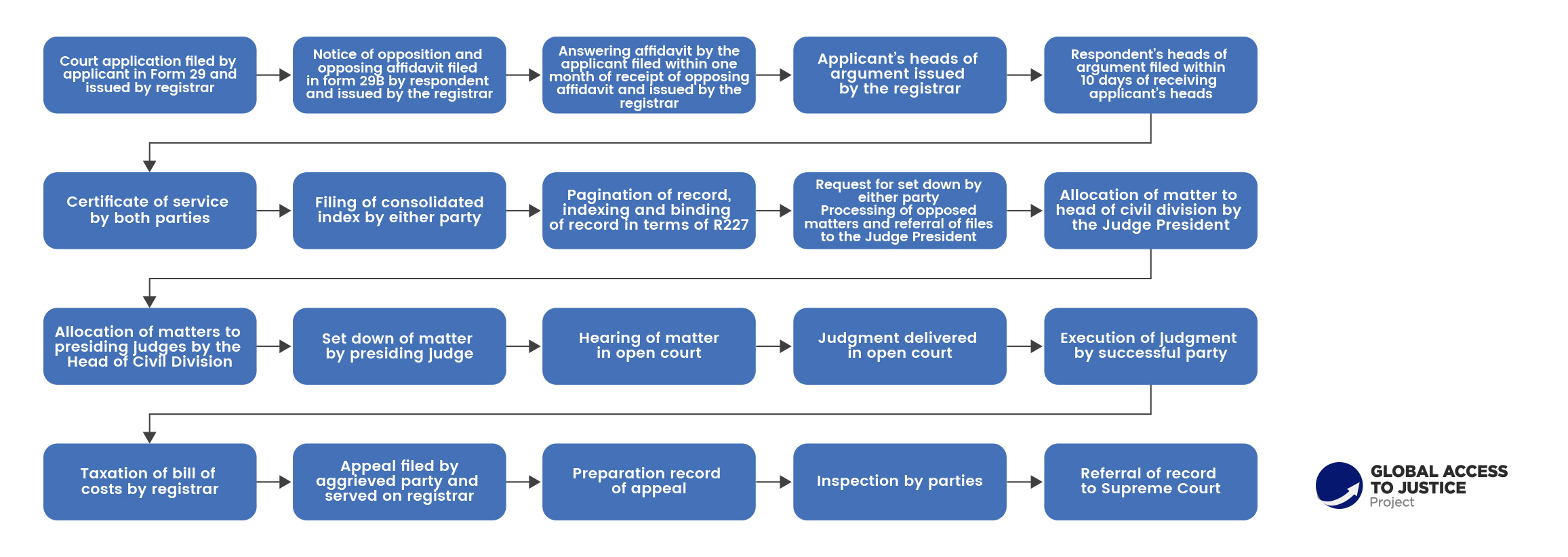

Barring concessions from parties, the court application stages in the High Court include the following:[17]

Barring concessions from parties, the court application stages in the High Court include the following:[17]

Chart 04. Court application stages in the High Court

In both civil and criminal procedures, parties can make interlocutory applications, raise technical objections and raise constitutional issues.[18]

In both civil and criminal procedures, parties can make interlocutory applications, raise technical objections and raise constitutional issues.[18]

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing formal legal processes

In sections 3.2 and 3.3, we discussed alternative dispute resolution methods as some of the ways of bypassing formal legal processes in Zimbabwe. Alternative dispute resolution is meritorious in that litigants are allowed to contribute to the reduction of the backlog of cases within the court system. Litigants are allowed to be self-actors and to serve legal costs. Where the litigants are allowed by the courts to pursue alternative resolution mechanisms, litigants voluntarily ask the courts to confirm their order by consent. The court’s confirmation has the effect of preventing litigants from coming back to court seeking an appeal or review of the order by consent.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

The Constitution provides for non-discrimination, right to administrative justice and right to a fair trial (see). Further, the Constitution also provides for the rights of accused persons.[1] The corollary to this is that courts of law and administrative tribunals are enjoined to ensure that accused persons enjoy the rights above which are guaranteed in the Constitution. The concern however still exists with the need to align the Administrative Justice Act (AJA) (Chapter 10: 28) with the Constitution. Specifically, AJA gives a monopoly to the High Court to be the court that provides the remedy to parties who are adversely affected by decisions of administrative bodies yet there is an Administrative Court that is constitutionally established. The Act also gives outright exemptions to certain State functionaries not to act reasonably, impartially, lawfully, with substantive and procedural fairness. The functionaries include the President when making executive decisions or in matters involving the appointment of judges. Further, the Prosecutor General is also given outright exemptions in matters involving the prosecution or decline of criminal cases.

The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, 2018 ranked Zimbabwe at 108 out of 113 countries on rule of law.[2] The Rule of Law Index measures eight factors of rule of law: constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice.[3] The WJP Rule of Law Index does not identify priorities for reform and is not intended to establish causation or to ascertain the complex relationship among different rule of law dimensions in various countries.[4] Zimbabwe’s overall rule of law score places it at 17 out of 18 countries in the Sub-Saharan Africa region and 11 out of 12 among low-income countries.[5] Low-income countries in 2018 included Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Nepal, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe.[6] In 2019, Zimbabwe has a global rank of 116 out of 126 countries.[7] In Africa, Zimbabwe ranked 26 out of 30 countries in 2019.[8] It also ranked 17 out of 20 low-income countries in 2019.[9] We shall now turn to discuss some of the key issues relating to legal aid in criminal and civil matters.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM[1]

5.1. History of legal aid

Legal aid existed in pre-colonial times in Zimbabwe even though Zimbabwe did not have a formal legal system then. When individuals were being prosecuted, rules were observed where self-actors had to be given the opportunity to assert their right to be tried in public. Through statements such as muranda nyangonaka haatongerwi mhosva asipo/ even a good servant has to be available when his or her case is being heard, the traditional courts observed rules that ensured that servants were not treated unjustly. Rules were also observed to show that the courts were impartial through statements such as dare harina ngava nemunhu or courts are impartial and do not just punish humans without reason. Formal laws on legal aid came with the introduction of British colonialism after 1890. Legal Aid in Zimbabwe is provided and funded through the Legal Aid Directorate, a department controlled by the Government under the Ministry of Justice Legal and Parliamentary Affairs. Legal aid is state-funded[2] and it is governed by the Constitution and the Legal Aid Act as the main pieces of legislation.

At an institutional level, State universities offer legal aid, for example, the University of Zimbabwe’s Faculty of Law has been running a legal aid clinic for long. The UZ Law Faculty now runs the Access to Justice Centre. Law-based organizations such as WILSA, ZWLA, ZLHR, NGO Forum, ZELA, and Musasa Project have legal help desks and normally advise women in selected magistrates’ courts across the country. The LRF immensely empowers the Zimbabwean society to access legal material on law reports, textbooks on various branches of the law, simplified versions on succession and other issues. Law-based organizations that are into human rights such as the ZLHR use mobile clinics, public interest, and strategic litigation as well as media platforms to foster a culture of human rights. Most civil society organizations also work under umbrella organizations such as the NGO Forum or National Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (NANGO).

Zimbabwe introduced a national law on legal aid in 1996, the Legal Aid Act[3] as a successor to the Legal Aid Representation Act.[4] Other important laws to consider included Order 5 of the Magistrates Court Rules which provided for pro-deo representation and Order 44 of the High Court Rules which requires litigants who wanted to be represented through the in forma pauperis procedure to apply to the Registrar so that they sue or be sued as a pauper. In criminal matters, the repealed Legal Assistance Representation Act gave the judicial officer powers to order that self-actors who could not afford legal practitioners be required to be represented.

The preamble of the current Legal Aid Act sums up the importance of legal aid in the following terms:

AN ACT to provide for the granting of legal aid to indigent persons; to provide for the establishment and functions of a Legal Aid Directorate and a Legal Aid Fund; to provide for the imposition of levies on legal practitioners for the benefit of the Legal Aid Fund; to repeal the Legal Assistance and Representation Act [Chapter 9:13]; to amend section 87 of the Legal Practitioners Act [Chapter 27:07], and to provide for matters connected with or incidental to the foregoing (underlining is intentional).

The role of lawyers in contributing to the legal aid fund is thus defined by statute. In this way, legal practitioners should also work with the legal aid directorate to ensure that the granting of legal aid is done efficiently. The new system of legal aid is provided in terms of the Legal Aid Act, 1996. The logical corollary to the above is that the Legal Aid Directorate (LAD) is obligated to ensure that legal aid to eligible persons who qualify as indigents. This is also buttressed by the fact that the Act enjoins the Director of LAD to be a registered legal practitioner. While the law officers under LAD need not be registered legal practitioners, they are also enjoined to treat themselves decorously under the Legal practitioners’ code of conduct over and above the requirements of policy directions of a general character given by the Minister of Justice.

The current Act lists the requirements for one to qualify for legal aid to the director of LAD. These include that the applicant must satisfy the Director that they have insufficient means to obtain the services of a legal practitioner of their own; have reasonable grounds for initiating, carrying on, defending or being a party to the proceedings for which he applies for legal aid; and; are in need or would benefit from the legal aid services provided in terms of the Act. The procedural safeguards on the application obligate the director to determine how the applicant is eligible for legal aid;[5]ascertain whether the resources including the Legal Aid Fund would be sufficient to assist the applicant, and to reject the application and inform the applicant of the reasons for the decision.[6] In granting the application, the director is given the discretion to request further information from the applicant on certain issues relating to the provision of legal aid emanating from the application.[7] This also includes the calling of the applicant to personally answer such questions that the director needs to clarify or those relating to the assessment of the applicant’s means.[8] The law also allows the director to reconsider his decision (to grant or reject the application) and it is assumed this may come after perusal of written representations from the applicant; or after the personal interviews.[9]

In 2013, the constitution-making process influenced the inclusion of the Constitution under the national objectives. Two things are worth taking note of with regards to the above. Firstly, legal aid is a relative right which is subjected to the availability of resources.[10] This constitutes an insufficient guarantee of legal aid to the majority. It often presents a scapegoat for the State to deny a litigant legal aid based on the unavailability of resources. Secondly, a wrong impression is created that legal aid only involves legal representation in Court. The provision of legal aid in Zimbabwe is further compounded by the fact that new players such as legal aid insurance companies are now providing insurance for legal representation. The concern, however, is that the legal expenses insurance companies are not regulated by the Law Society of Zimbabwe; that perhaps some lawyers run these societies; and that IPEC may not efficiently regulate the companies without partnering the Law Society of Zimbabwe.

In civil matters, poor litigants may be represented through the in forma pauperis procedure. To protect the poor litigants from being short-changed by legal practitioners, the High Court noted that lawyers should avoid incompetence and unprofessional conduct and should also seek the leave of the court if they want to renounce agency in IFP cases.[11] The challenge with IFP representation is that lawyers sometimes raise concern that rich clients purport to be without means and only brag about their riches after the case has been finalized in their favor. Further, some clients do not disclose the fact that they would have received orders of perpetual silence from the courts. However, this also demands that lawyers must be thorough in dealing with the superior courts’ registrars when handling IFP cases. In criminal cases, accused persons facing serious offenses such as murder normally get representation through the Pro-Deo representation. The High Court Registrar allocates cases to both senior and junior lawyers. Concern that can be raised however is the extent to which lawyers fresh from college are usually allocated complex murder cases.

5.2. The legislative framework for legal aid

The Constitution is the mother law which provides for legal aid in Zimbabwe. Legal aid is also governed by national law, the Legal Aid Act (see 5.1). The Legal Practitioners Act also contains various ethical considerations that bear significantly on the provision of legal aid in Zimbabwe. These include the need for lawyers to respect their duties to the court, clients and fellow legal practitioners when defending the cause of their clients. For instance, the lawyers can be awarded costs de bonis propriis in instances where they act with recklessness or gross negligence.[12] Challenges however still exist whether lawyers are entitled to both their legal fees and commission for collection of debts.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

The provision of legal aid is supervised by the Ministry of Justice Legal and Parliamentary Affairs through the LAD (see section 5.1).[13] LAD must ensure that it is decentralized to all provinces in Zimbabwe in line with its vision which focuses on ‘ensuring that all indigent persons have access to justice regardless of their geographical location in Zimbabwe.’[14] While the legal aid directorate does not charge any legal fees to its clients, clients may be required to pay a small contribution to support the Legal Aid Fund.[15] It has been shown in section 5.1 that the head of LAD must be registered lawyer although other law officers in the LAD need not be registered lawyers. This is important especially for lawyers who are trained outside Zimbabwe who may be employed pending the writing of conversions examinations. The Magistrates’ Court’s clerk of court and the High Court Registrar are also critical in ensuring that the Magistrates and High Courts play a huge role in the provision of legal aid (see section 5.1). Critical challenges in the state-run legal aid relating to the budgetary allocations of funds to the LAD by the Ministry of Justice.

The provision of legal aid by the Law Society of Zimbabwe usually benefits clients who would have been duped by their lawyers. They benefit from the Law Society Compensation Fund. Other institutions that are important in the provision of legal aid have been shown above in section 5.1 to include students at universities that have law schools, law-based organizations, and legal aid societies. The major challenge that emanates from legal insurance societies is that they are not regulated by the Law Society and that IPEC and the Law Society must clarify how the regulatory aspects would be. This would go a long way in ensuring that lawyers who run some of the insurance companies will do so professionally and will not use the societies to diss other lawyers or to tout for clients. Human rights or law-based organizations should also broaden their representation to other areas of the law besides human rights. This will ensure

5.4. Legal aid budget

There is a dearth in the literature on the legal aid budget in Zimbabwe.[16] Some available information on budgetary allocation is not recent but indicates that LAD had offices in Harare, Gweru, and Bulawayo but failed to open the Mutare office due to financial constraints.[17] This is the case even though financial resources are managed under the legislative framework that includes the Public Finance Management Act [Chapter 22:19], Treasury Instructions; the LAD Regulations and other financial controls such as internal and external audits and approval of any expenditure by the Procurement Committee.[18] As such 80 percent of those who need legal assistance in Zimbabwe do not have access to it.[19] There has been a call to fund legal aid in Zimbabwe effectively to improve legal services.[20] Further, the money that is allocated to the legal aid fund does not fulfill its intended purpose since it is consumed by operational costs and LAD does not have a strategy for resource mobilization.[21] There has been information on funding of others from the perspective of vulnerable groups such as women[22] and NGOs which provide legal services in Zimbabwe such as the Legal Resources Foundation.[23]

5.5. Legal aid providers

Legal aid in formal courts in Zimbabwe is provided by many actors. Lawyers in private practice, advocates from de facto bars as well as law-based organizations such as NGO Forum, Justice for Children’s Trust, ZLHR,[24] ZWLA,[25] WILSA,[26] among others. Some organizations such as Musasa Project provide counseling, medical care, temporary shelters, and legal support to women survivors of violence, as well as teaching them the skills they need to live independent, violence-free lives.[27] In other tribunals, some persons can provide legal advice even without a formal legal education. The Magistrates Court (Civil) Rules, 2019 provide that parties who may institute or defend proceedings include persons acting in their capacity;[28] legal practitioners;[29] officers from local authorities, companies or incorporated bodies;[30] members of partnerships;[31] and persons authorized by law.[32] It was also shown in section 5.1 that legal insurance companies are now assisting by finding lawyers for their clients.

5.6. Quality assurance

Decisions taken by the Legal Aid Directorate are not strictly monitored as there are concerns that some cases where litigants are advised to approach lawyers in private practice or the High Court registrar for IFP representation. There are also no set criteria to prevent instances where direct referrals of clients from the Ministry of Justice officials may assist law officers to refuse to take up such cases. The Act seems to give every decision-making process to the director yet in most instances the law officers are seized with the vetting and screening of civil and criminal cases. Administratively, the director then allocates accepted cases to the law officers. While the director of LAD monitors and supervisors law officers, there is a need to ensure that there is an effective mechanism where officers in the LAD do not shun some cases especially those relating to criminal cases. There is also a need to ensure that poor clients are not forced to contribute to the administrative fee before their cases are accepted as they are normally without any means. On the work of the various lawyers regulated by the law society, quality assurance is based on the fact that the LSZ is very innovative on issues such as practice management and discipline of errant members of the profession. The LSZ administratively conducts spot checks on private law firms to see if lawyers are complying with its rules on law firm management. Those not complying are sometimes forced to undergo pupillage training. The LSZ does not also wait for complaints to address issues that bear on the conduct of its members. It usually responds to media reports. Quality assurance is also promoted by the law society’s move to allow senior and junior lawyers to form various organizations such as the Young Lawyers Association, Zimbabwe Legal Social Forum (ZLSF) and others. Some issues include the involvement of members to raise objections on registration of lawyers or to contribute to their appointment to the Law Society Council. Organizations that do not run law firms such as non-governmental organizations are given partial practicing certificates to ensure compliance with the trust account management rules. While the Law Society of Zimbabwe regulates registered lawyers, there is no mechanism to allow it to regulate law officers who may be employed under the Ministry of Justice but are not yet registered with the Law Society. There is currently no clear regulatory framework on legal insurance firms under the micro-insurance regime. The regulatory framework through Statutory Instrument 39/2018; Insurance (Amendment Regulations 2018; and Insurance and Pensions Commission (Levy) Regulations 2018 do not specifically address the issue of legal aid insurance firms from the perspective of administrative justice or access to justice. Even the laws on insurance such as the Insurance Act;[33] Insurance and Pensions Act;[34] the Pensions and Provident Act[35] have not been reformed in line with the current wave of legal aid firms. There is thus need to find ways of regulating, de-regulating and re-regulating certain firm operations in line with the spirit of the times. There is also currently no law to regulate how lawyers can not be used as smokescreens in money laundering or in instances where they are paid using proceeds from crime. Under the Money Laundering and Proceeds of Crime Act.[36] Lawyers have to be paid for their work but should not intentionally offer their services to assist their clients to evade justice.[37]

5.7 Criminal Legal Aid

5.7.1. Scope of Criminal Legal Aid

Criminal legal aid is now constitutionally regulated.[38] By way of general considerations in criminal proceedings, the victim of a crime is called the complainant. The State’s prosecutor acts on behalf of the complainant through the authority to prosecute from the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The person against whom a criminal complaint is made is called the accused person. A complainant reports his or her case at the police station’s charge office. The police effect will then effect an arrest. In some instances, peace officers or private citizens arrest an offender. The members of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission can now arrest corruption suspects.[39] While the police, peace officers and private citizens can arrest suspects, lawyers can only exercise their rights to arrest under the category of citizens’ arrest. The Prosecutor General or public prosecutors may decline to prosecute and a private prosecutor is appointed.[40] Witnesses who testify in court are usually reimbursed for their travel expenses. Victims may benefit from the trial in-camera and young children may have services of an intermediary. Young offenders are represented by probation officers. The court is enjoined to ensure self-actors are properly advised of their rights. Although courts frequently ask self-actors if they have complaints against the police, the challenge in most cases is that self-actors who are assaulted in police custody are sometimes further remanded in custody without investigation of their assault. Even though the court sometimes orders the State to investigate the assault, in most cases the State does not provide feedback to the court and this impacts negatively on the accused person’s right to a fair trial.[41] Further, accused persons who are mentally-incapacitated usually have the verdict of not guilty retained in instances where the medical evidence is presented. Psychiatrists and medical doctors play an important role in the examination of accused persons who are suspected of being mentally-incapacitated. The challenge, however, is that there are few psychiatrists to cover the many lower courts in Zimbabwe.

Further, doctors usually raise concerns that the medical affidavit form does not allow them to provide enough detail on the history of the complainant. Further, the medical affidavit does not contain a clause that obligates doctors to be impartial when examining the complainant. In most instances, medical doctors simply indicate the nature of the offenses and do not provide detail on likely causes that could cause the injury that would have been sustained by the complainant. Another challenge is that even in instances where the accused is acquitted for reasons of insanity, the relatives usually refuse to accept him or her for fear that he would re-offend. This again influences how lawyers are willing to represent accused persons through pro-deo representation.[42] In simple, legal aid in criminal cases can be offered from the public fund under the LAD, from lawyers in private practice, law-based organizations that do pro-bono work and pro-deo systems.

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

Those who are eligible for pro deo representation are normally those accused in murder cases. The fees are meager but assigned lawyers are obligated to expect the cases assiduously; avoid last-minute interviews, avoid rapidly drawn defence outlines and superficial presentation of the cases at trial.[43] An accused person who is not able to access legal representation at their own expense can be assisted by the State (see section 5.7.1). The High Court Criminal Registrar will assess the application and allocate cases to lawyers on the law society register. Others who are accused of criminal offences usually that bear on public violence or political rights are represented by law-based organizations such as the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights.[44] Accused persons can also be represented by lawyers from the Legal Aid Directorate.

5.7.3. Process for obtaining criminal legal aid

The process is now constitutionally regulated as was shown in section 5.7.1. The State can assist accused persons or spouses, counselors and relatives of accused persons who can assist them in situations where they can afford legal representation. Currently, legal aid societies also choose lawyers for their clients. For those who are represented by private lawyers, legal aid is usually from the accused person’s family, religious organization, friends or company. For those represented by law-based organizations, legal aid is usually from donor funds. For those who are represented on a pro-deo basis at the High Court, the High Court Criminal Registrar chooses a pro-deo counsel from lawyers on the roster provided by the Law Society of Zimbabwe. The letter contains the Registrar’s refer and details relating to the accused person’s name, criminal record book number; trial date, court venue, and charge. The chosen lawyer is also advised to make an application to a judge to be excused if he is unable to do the case. If excused by the court, the lawyer has to give the papers to the judge’s clerk. The challenge is normally that the High Court registrar does not provide the pro-deo lawyer with the accused person’s lawyer. In most instances, the letter contains a provision where the lawyer is required to contact the Attorney General’s office (now Prosecutor General’s office) with the view to finding out where the pro-deo accused would be interviewed. This normally causes lawyers to shun the pro-deo representation as they are made to look for clients. Sometimes the PG’s office will not be aware of the client’s whereabouts. Sometimes the accused person will be in a remand prison that is not in the city, or town where the lawyer is operating from. This greatly impacts how lawyers adequately prepare for trial. The lawyer is however normally advised to submit defence outline for the accused four days before the trial date and must also serve the PG’s office. If they fail to locate the accused, they are also expected to advise the judge and the PG’s office so that arrangements are made not to burden the court or witnesses with preparing for trial.

5.8. Civil Legal aid

Civil legal aid can be obtained from legal aid funds, lawyers in private practice; law-based organizations or on IFP basis. The lawyers at the Legal Aid Directorate can offer public legal aid in cases at the Magistrates and High Court.

5.8.1. The scope of the public legal aid scheme

To be eligible for public legal aid, the litigant must satisfy the criteria listed in section 5.1. The director of the LAD has to satisfy himself or herself if the funding is available to enable someone’s case to be defended publicly. Those who benefit from the public legal aid under IFP have to be interviewed by the High Court Registrar civil and Clerk of Court at the Magistrates Court. Lawyers in private practice who are allocated IFP cases can also liaise with the registrar and clerk of the court to see if indeed the applicant qualifies under IFP.

5.8.2. Eligibility criteria for civil legal aid

Generally, public civil aid under LAD representation requires the applicant to satisfy the indigent and means test. Those who sue under IFP must demonstrate that they are paupers. For IFP requirements in the Magistrates Court, there is a need for the applicant to demonstrate that he is normally resident within the jurisdiction of the court and desires to bring or defend proceedings in IFP.[45] The clerk of court considers the affidavit that sets in full the person’s financial position and does not have the property to the value of one thousand dollars and will not be able to produce such amount within a reasonable time.[46] The applicant is not required to demonstrate that his or her household goods, wearing apparel and tools of trade affect his financial position.[47] If the clerk of the court is satisfied that the applicant meets the above criteria, he or she is obligated to refer the applicant to a legal practitioner selected from a roster of names furnished to the clerk of court by the Law Society.[48] If in doubt, the clerk of court can right to a district officer of the Department of Social Services for a report on the Applicant’s means.[49]The chosen lawyer is obligated to inquire into the applicant’s means and the merits of his or her cause before taking instructions to represent such a person.[50] The clerk of court will accept IFP cases if they are accompanied by the affidavit from the applicant and a lawyer’s signed statement that the applicant is being represented gratuitously in the proceedings.[51] In the High Court, IFP starts with the initial consultation with legal practitioners or department of social services.[52]

5.8.3. Process for obtaining civil legal aid

As has already been described above, applications for legal aid are decided by the Legal Aid Authority, unless the matter is already before a court, then the court decides on legal aid. An application for legal aid must be preceded by consultation with a lawyer or other legal practitioner (see section 5.8.1).

6. COSTS OF RESOLVING DISPUTES WITHIN THE FORMAL JUDICIAL MACHINERY

6.1. Overview of judicial costs for litigants

To file a claim at court in a civil case in the magistrates’ court, the plaintiff must pay for summons, appearance to defend, and other processes. The amount payable is dependent on the value or size of the claim, usually $30rtgs for values of or below 100000rtgs. The magistrates’ court has jurisdiction to hear cases amounting to $300000rtgs. If the claim is a small claim case parties can also approach the small claims court. Because magistrates’ courts are normally far away from lawyers of choice, some lawyers prefer to institute cases below $300000rtgs at the High Court. The High Court is a court of competent jurisdiction for all cases. Lawyers may, however, be asked to justify why they avoid the magistrates’ court in instances where the magistrates’ court would have been preferable. The most significant reason lawyers give is that the High Court is efficient. In the Zimbabwean civil system, lawyers may be taxed using a high bracket in instances where they ought to have commenced proceedings in the magistrates’ court. Some judges at the High Court, however, do not insist on the monetary jurisdiction. The costs of legal representation in Zimbabwe include those that are litigant financed, those from publicly funded and third party funded legal representation. Donor funds are normally used for third party funding in human rights and public interest cases.

6.2. Exemption from judicial costs

Amicus curiae or friends of the court are not required to pay legal costs as they are normally invited by the court based on their expertise. The rules of the Constitutional Court provide that no order of costs can be made against the amicus curiae.[1] Intervening litigants may however not be exempted. The lawyer representing a litigant on the IFP basis may claim his or her costs from the costs against the losing party.[2]

6.3. Mechanisms to reduce costs by variations to courts and procedures