National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

1.1. Form of government

Aotearoa[1] New Zealand is a parliamentary democracy where almost all laws are national (regional laws are generally confined to local infrastructure and planning). The 120-seat parliament is elected under a Mixed Member Proportional System, dominated by two parties left and right of centre, which rely on the support of smaller parties.

New Zealand’s government system is based on the doctrine of separation of powers. Each of the three branches of government (the Legislature, the Executive, and the Judiciary), balances the other two branches.

The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi (1840) (The Treaty of Waitangi) is an important constitutional document that established the legal and political relationship between the Crown/colonial government and the indigenous Māori population. Although the Treaty was “intended to create unity”, different understandings of its key words, and breaches of it, have caused conflict[2]. Following pressure from Māori Members of Parliament, the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 was passed, which gave the Treaty statutory recognition. From the mid 1980s acts of parliament began to include references to the Treaty of Waitangi and its principles, which allowed the courts to interpret the extent to which Treaty principles are raised in any case covered by the relevant legislation[3]. All Crown entities (including government departments, state-owned enterprises, public schools and hospitals) and local authorities are required to conduct business in a manner consistent with the Crown’s obligations as a Treaty partner. This means that the needs of Māori and the inequities faced by them must be taken into account. How well this is done in practice remains a subject of significant debate.

1.2. Demographics, ethnic groups, languages and religion.

The 2018 census records New Zealand population at 4,699,755. New Zealanders identify as European (70.2%); Māori (16.5%); Pacific (8.1%); Asian (15.1%); Middle Eastern, Latin American, African (1.5%); or other (1.2%). There are three official languages: English, Māori, and New Zealand Sign Language.

The 2018 census reported that almost half of the population (48.2%) had no religion. Of those that do have a religion, there is a diverse range with 157 different religious affiliations. The top five denominations are: Anglican (6.7%); Christian (no denomination specified, 6.6%); Roman Catholic (6.3%); Presbyterian (4.7%); and Catholicism (not further defined) (3.7%).

1.3. Social and economic environment[4]

The gross domestic product (GDP) for New Zealand over the last 10 years is reported in Chart 01. The gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita is $33,970.[5]

Chart 01. New Zealand GDP from 2010 – 2018, reported in US Dollars and NZ Dollars

In New Zealand, inequality is generally measured by the P90/10 (or P80/20) ratio. This ratio shows the difference between high household incomes (those in the 90th percentile) and low household incomes (those in the 10th percentile); the higher the ratio, the greater the level of inequality.[6] In 2017, household incomes (before accounting for household costs) at the 90th percentile are around 4.06 times the level of incomes of households at the 10th percentile; this difference is 5.68 after accounting for housing costs[7]. The Gini coefficient (despite the methodological limitations) is also calculated: reporting a score of 34.4 (before accounting for household costs). The Gini coefficient is also reported using square root equivalence scale to allow for OECD comparisons[8]. The United Nations Development Programme inequality-adjusted index reported for New Zealand in 2017 was 0.846.

Between 2016 – 2018, a New Zealander’s life expectancy at birth was 80.2 years for males and 83.6 years for females[9]. In 2017, a New Zealander’s life expectancy at birth is 80.4 years for males, 83.7 years for females, and 82 years overall[10].

The United Nations Development Programme recently reported the expected years of schooling is 18.8 years and the mean years of schooling is 12.7 years[11]. In 2019, New Zealand’s Human Development Index was 0.921, ranking New Zealand 14th.[12]

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of legal system

New Zealand is a common law jurisdiction with a Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. It has a single house of parliament and an independent judiciary. The constitution is comprised of a number of separate laws and conventions. The Treaty of Waitangi is an important constitutional document and is also incorporated by statute into certain areas of law.

2.2. Organization of the justice system

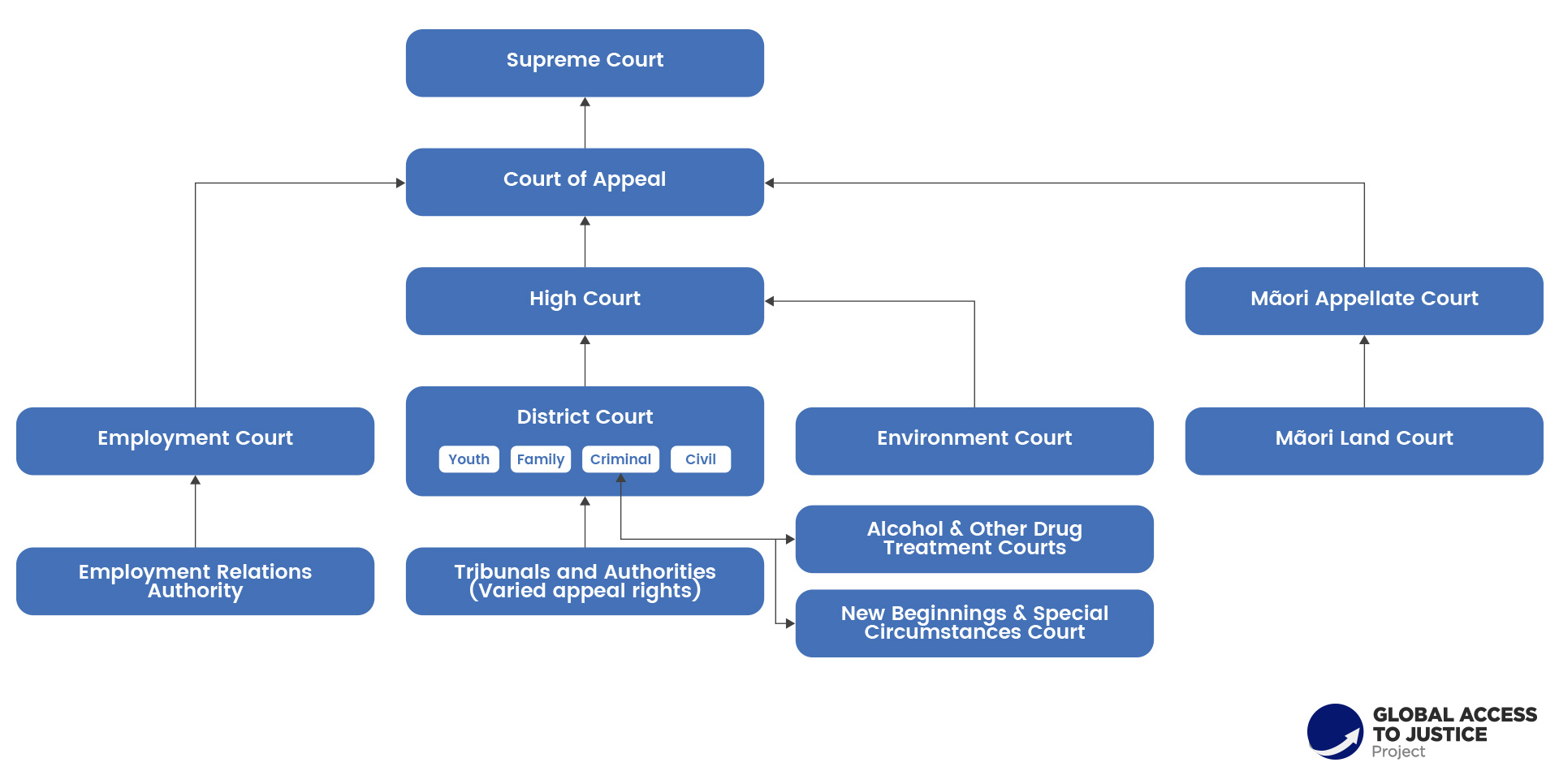

New Zealand’s justice system is unitary but with multiple levels. The highest court is the New Zealand Supreme Court, which was established in 2004 to replace the United Kingdom Privy Council as New Zealand’s final court of appeal. The other general courts, in descending order, are the Court of Appeal, High Court, and District Court. The District Court, which hears civil and criminal matters, also includes the Youth Court and Family Court. New Zealand also has three specialist courts: Employment Court, Environment Court, and Māori Land Court.

The Māori Land Court was established in 1865 to convert customary Māori land into titles that could be acquired, initially by the colonial government and later by individual settlers. Since the passing of Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993,[1] the Court’s role is to:

(a)Promote the retention of Māori land in the hands of its owners, whānau[2], and hapu;[3]

(b) Facilitate the occupation, development, and use of Māori land; and

(c) Ensure that decisions made about Māori land are fair and balanced taking into account the needs of all owners and their beneficiaries.

The Māori Land Court’s website contains information about the Court’s history and its present-day functions[4].

In addition to courts, New Zealand has a large number of tribunals and authorities. These are expert forums that have legislated authority to resolve a range of civil disputes, but are under the supervisory jurisdiction of the District Court or the High Court. There are a number of civil claim tribunals that provide quick and inexpensive ways to settle a dispute as they are less formal than a Court. The Disputes Tribunal, for example, can resolve small civil claims that have a value of no more than NZ$30,000.

The Waitangi Tribunal is a standing commission of inquiry. It makes recommendations on claims brought by Māori relating to legislation, policies, actions or omissions of the Crown that are alleged to breach the promises made in the Treaty of Waitangi. The role of the Tribunal is set out in section 5 of the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and includes:

(a) inquiring into and making recommendations on well-founded claims;

(b) examining and reporting on proposed legislation, if it is referred to the Tribunal by the House of Representatives or a Minister of the Crown; and

(c) making recommendations or determinations about certain Crown forest land, railways land, state-owned enterprise land, and land transferred to educational institutions.

In fulfilling this role, the Waitangi Tribunal has exclusive authority to determine the meaning and effect of the Treaty. It can decide on issues raised by the differences between the Māori and English texts of the Treaty.

New Zealand has three therapeutic courts within the criminal District Court system. These therapeutic courts aim to address issues that contribute to a person’s offending, in particular alcohol and other drugs, and homelessness.

The Youth Court system also includes Rangatahi[5] and Pasifika Courts which apply the same law and procedure as any other Youth Court, but on a marae[6] or Pasifika community setting, and incorporate Māori and Pacific languages and protocols. Young people of any ethnicity may be referred to these courts if they admit to their offending, and if the victim consents.

A Rangatahi Court hearing is held on a marae, and facilitated by a Youth Court Judge together with kaumatua[7] and/or kuia[8]. Hearings begin with a pōwhiri[9], and the young person is required to learn and deliver a pepeha[10]. Kaumātua or kuia may offer advice to the young person, and some Rangatahi Courts provide access to tikanga[11] learning programmes. There are 15 Rangatahi Courts in New Zealand. Pasifika Courts operate in a similar way to the Rangatahi Courts. Pasifika Courts are held at Pasifika churches or community centres. A judge will facilitate the hearing with assistance from Pasifika elders. There are two Pasifika Courts, both in Auckland.

Chart 02. Hierarchy of New Zealand Courts and Tribunals

Māori customary law is recognised in New Zealand law provided certain criteria are met. Specifically: the custom is long standing, it is has continued without interruption since its origin, it is reasonable, it is certain in its terms, and it has not been displaced by Parliament through clear statutory wording.

Māori customary law is recognised in New Zealand law provided certain criteria are met. Specifically: the custom is long standing, it is has continued without interruption since its origin, it is reasonable, it is certain in its terms, and it has not been displaced by Parliament through clear statutory wording.

2.2.1. Court workloads

In New Zealand, the District Court deals with the bulk of the cases, and sees upwards of 200,000 criminal, family, youth and civil matters every year. Most of the court’s work comprises criminal cases. Each Court reports biannually on the number of new cases in the reporting period (“new business”), the number of cases disposed during the reporting period (“disposals”) and the number of active cases ongoing at the end of the reporting period (“active cases”). See Chart 03 for the District Court statistics for the period between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2019.

Chart 03. Court workload statistics for the District Court for the period between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2019.

| Criminal | Family | Youth | Civil | |

| New Business | 132,705 | 60,985 | 3,653 | 895 |

| Disposals | 131,516 | 59,472 | 3,703 | 712 |

| Active Cases | 34,434 | 25,946 | 918 | 695 |

The High Court considers a much smaller number of criminal matters, but these are more serious offences. In the same reporting period, there were 164 criminal trials held, and 1241 criminal appears were filed. There are a much larger number of civil cases, however. In the same reporting period, 2,139 new civil cases were filed in the High Court, 2,285 were disposed of, and 2,845 were still active.

The two higher appellate courts understandably see a much lower volume of cases. In the same reporting period, the Court of Appeal delivered 672 judgments, and the Supreme Court delivered 16 substantive judgments and 105 judgments for leave to appeal.

There are some concerns regarding the way court workload statistics are generated in New Zealand, and whether they can in fact answer research questions that target issues relating to access to justice[12].

2.3. Structure of the legal profession

In New Zealand, all practitioners are admitted to the High Court of New Zealand as barristers and solicitors. It is not possible to be admitted only as a barrister or only as a solicitor, nor on a limited basis in order to practice in only one area of law. A lawyer may, however, choose to practice only as a barrister (i.e. as a barrister sole).

Under New Zealand’s Lawyers and Conveyancers Act 2006, only people holding current practising certificates issued by the New Zealand Law Society (NZLS) and incorporated law firms may call themselves ‘lawyer’, ‘law practitioner’, ‘barrister’, ‘solicitor’, ‘counsel’, and other terms. Most lawyers, including those who practice only as solicitors, hold certificates as ‘barristers and solicitors’. This entitles them to act as solicitors and to appear in the courts.

New Zealand’s barristers and solicitors are not permitted to practise in partnership with members of other professions. They are not permitted to practice with lawyers holding only foreign qualifications, although some New Zealand law firms are associated with foreign law firms while remaining legally independent entities.

Law firms may be either partnerships constituted by way of partnership agreement, or “incorporated law firms”, which operate as limited liability companies. Barristers may also operate under the incorporated law firm structure.

A lawyer who wishes to operate as a sole practitioner to become a partner of a law firm or a director/shareholder of an incorporated law firm must be approved by the NZLS to “practice on their own account” as a barrister and solicitor. Applicants for approval must undertake training regarding business administration and the administration of lawyers’ trust accounts, and must satisfy the NZLS that they are a fit and proper person to practice on their own account[13].

2.3.1. Number of licensed practicing lawyers

The most recent survey of the New Zealand profession revealed that there are 12,923 registered lawyers (Female = 6661; Male = 6261), with the majority practicing in multi-lawyer firms (58%). The remaining lawyers are either in sole practice (4.8%); barristers sole (9.7%); or in-house lawyers (22 percent)[14].

Although female lawyers now form the majority of the profession, few are in senior positions. For example, only 34% of partner or directors in multi-lawyer firms are female, despite the workforce in these same firms having 63% female. Similarly, 77% of Queen’s Counsel are male and 21% female[15].

The ethnicity of the legal profession is also not reflective of New Zealand society. Only 30% of the legal profession do not identify as NZ European, and only 6% identify as Māori (Māori are approximately 16% of New Zealand’s population).

2.3.2. Affordability of legal fees

In New Zealand, legal services are typically charged by the billable hour. Three surveys have attempted to quantify the average rate of the billable hour, with the best estimate sitting between $250 and $350 per hour (range = $23 – $680 per hour)[16]. The price of legal fees has a direct impact on the accessibility of justice in New Zealand. In the 2006 legal needs national study (see section 10 for discussion), lawyers’ fees were identified by respondents as a significant contributing factor as to why people with a legal problem do not approach a lawyer for help. The legal aid scheme, however, does not provide a comprehensive solution (see section 5 for discussion). Many New Zealanders remain shut out of the legal system because they are unable to afford legal fees.

2.3.3. Legal representation in court

New Zealanders are permitted to bring proceedings before the court without legal representation. In some of the Tribunals (e.g. Disputes Tribunal) parties are barred from appearing with legal representation, whereas in other tribunals such as the Human Rights Review Tribunal and Employment Relations Authority, legal representation is allowed.

Lay advocates are also allowed in some New Zealand courts (e.g. Youth Court, Employment Court) and tribunals (e.g. Human Rights Review Tribunal). Lay advocates take an advocacy role to represent – and communicate – the interests of one of the parties[17].

McKenzie friends are increasingly appearing in New Zealand courts to assist parties that appear without legal counsel (one to three cases per year between 1992 and 2012; 22 cases in 2015)[18]. The scope of the role for McKenzie friends was recently considered in the High Court decision of Craig v Slater [2017] NZHC 874, where it was held that the McKenzie friend could sit beside the party; take notes; quietly make suggestions or give advice; propose questions and submissions to the party, who might repeat them; and in rare circumstance, with leave address the court. The role of McKenzie friends, or any support person, has not been codified in New Zealand statute. There is currently debate in New Zealand about whether the role and scope of McKenzie friends should be formalised, and address problematic questions about who can be a McKenzie friend (i.e. can a practicing lawyer) and whether the service should be regulated.

2.3.4. Representation by Paralegals/Legal Executives

The term “paralegal” is not used in New Zealand. Two legal support roles which require registration do exist: licensed conveyancers and legal executives.

“Conveyancing” is described by the New Zealand Society of Conveyancers as “the legal work required to transfer the ownership of real estate from one person or entity to another, which also includes the processing of subdivisions, leases and refinancing of mortgages”[19]. The Lawyers and Conveyancers Act 2006 provides the framework for the conveyancing profession in New Zealand, including setting out the qualifications and other attributes required, and conveyancers are subject to the Act’s disciplinary regime. The New Zealand Society of Conveyancers website lists 57 “conveyancing practitioners” and six “registered conveyancers” on its website[20]. While there may be conveyancers who have not identified themselves on the society’s website, it is clear that very few individuals have chosen this area of work.

Legal executives are not qualified as lawyers, but must hold the New Zealand Diploma in Legal Executive Studies or its predecessor qualification. Legal executives are skilled in particular aspects of law, generally specialising in residential and/or commercial conveyancing, estate administration and/or planning, trust administration and/or formation, and some aspects of litigation (but they may not appear in Court). Legal executives may be registered with the New Zealand Institute of Legal Executives (NZILE), which differentiates their qualifications and skills, and gives them the power to witness signatures in some circumstances. As employees of law firms, legal executives may be subject to the disciplinary regime under the Lawyers and Conveyancers Act 2006 (see sections 11 and 14). The NZILE website states that there are over 1100 registered legal executives in New Zealand[21].

2.4. Career of Judges

The judiciary is the third branch of Government, separate to the Legislature and the Executive. The judiciary is responsible for interpreting and applying the law set by the Legislature, and for examining the actions of the Executive through the process of judicial review. Conversely, the Executive is involved in the selection of Judges, and both the Executive and the Legislature are involved in the dismissal of Judges in the event of misconduct.

The Governor-General – on recommendation from the Attorney-General – makes the majority of judicial appointments. Candidates must have held a practising certificate as a barrister or solicitor for at least seven years. They can respond to a request for expression of interest, be nominated, or be invited to apply. To be successful, the candidate:

… must be of good character, have a sound knowledge of the law and of its practice, and have a real sense of what justice means and requires in present-day New Zealand. They must have the discipline, capacity and insight to act impartially, independently and fairly.[22]

Extensive consultation is carried out at various stages in the appointment process, but this is carried out on a confidential basis. The Attorney-General must act independently of party-political considerations.

The NZLS provided a snapshot of the judiciary in 2019[23]. In total, there were 237 permanent members of the judiciary, with 65% being male. In the Supreme Court, however, the bench consists of three women and three men. The 2013 Census data – the only publicly available data – showed that 93% of judges reported being of European ethnicity, and 10.8% reported being of Māori ethnicity. In response to requests for ethnicity data: “The office of the Chief District Court Judge stated at 1 March 2019, 19 District Court judges were Māori, 3 were Pasifika, and 2 were Indian. It noted that some judges identify with more than one ethnic group. The Māori Land Court advised that of the 11 permanent and two acting members of the Court, 11 identified with and had Māori ancestry.”[24]

A Judge’s tenure continues until either their resignation, their retirement, or their removal from office. Judicial retirement is required when a judge turns 70. After that age, a judge can return to the bench on acting warrants which are granted on two-year terms until the judge is 75 (Senior Courts Act 2016, ss 116 and 133).

2.5. Career of Prosecutors

2.5.1. Types of Prosecution Services

The Solicitor General, who is also the Chief Executive Office of the Crown Law Office, is responsible for the general oversight of the public prosecution of all criminal offences in New Zealand. In practice, prosecutors from the Criminal Team in the Crown Law Office only carry out criminal appeals in the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. Crown Solicitors are responsible, pursuant to a Crown warrant, for prosecuting serious crime on behalf of the Crown. Crown Solicitors are lawyers in private practice firms, paid by Crown Law in respect of their Crown prosecution work. There are currently 17 Crown Solicitors warrants which are held by partners in private law firms throughout New Zealand. Crown Solicitors can delegate the legal work to other employees in their firm, who are classified as either principal, senior, intermediate, or junior prosecutors.

The Police Prosecution Service is embedded into New Zealand Police. It is responsible for carrying out criminal, traffic, youth, and coronial prosecutions (except where the proceeding becomes a Crown Prosecution). There are 212 police prosecutors who service over 60 District Courts throughout New Zealand. Prosecutors are also embedded in various Government agencies, and are responsible for carrying out prosecutions under legislation administered by the agency – this is discussed in further detail at 3.1.2.

2.5.2. Recruitment

Permanent positions for prosecutors are publicly advertised using both general online situations vacant platforms as well as the New Zealand Government’s Jobs Online platform. Fixed-term positions for prosecutors might only be advertised internally (e.g. through the Government Legal Network).

2.5.3. Appointment Period

Prosecutors who are employed at Crown Law or other Government agencies are subject to New Zealand employment law. There is no compulsory retirement age.

Crown Solicitors are appointed by a warrant. A Crown Solicitor’s warrant is held at pleasure, and can be revoked. The Solicitor-General carries out periodic reviews to ensure high prosecutorial standards are achieved and maintained. A Crown Solicitor can also resign the warrant by Letter to the Solicitor-General. Crown Solicitors are required to give 90 days’ notice of resignation, unless exceptional circumstances apply (e.g. they are being appointed to the judiciary). In practice, there is a long tradition of the Crown Warrant being awarded to successive partners in the same firm. For example, in New Zealand’s capital city, Wellington, the Crown Warrant has been held by the same firm since 1936.

2.6. Availability of Legal Services

As in many jurisdictions, legal services are not readily available to all New Zealanders. One particular concern is the shortage of lawyers offering civil legal aid services. This is recognised across the profession, but to date, no solution has been achieved. The most significant recent recognition of this issue came from the swearing in speech of New Zealand’s new Chief Justice, the Right Honourable Dame Helen Winkelmann, on 14 March 2019:

Without knowledge of the law many do not know they have a problem with which the law can help them. The cost of legal representation is so great that it is only the well to do who can afford a lawyer to represent them in court. There are few lawyers practising civil legal aid, and fewer still in areas of need. For those who decide to go it alone and attempt to represent themselves, there is still the considerable cost barrier of court fees, and the difficulty of court procedure.

Access to affordable legal services remains a problem in New Zealand, and is addressed throughout this report.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal procedure

3.1.1. Criminal investigations

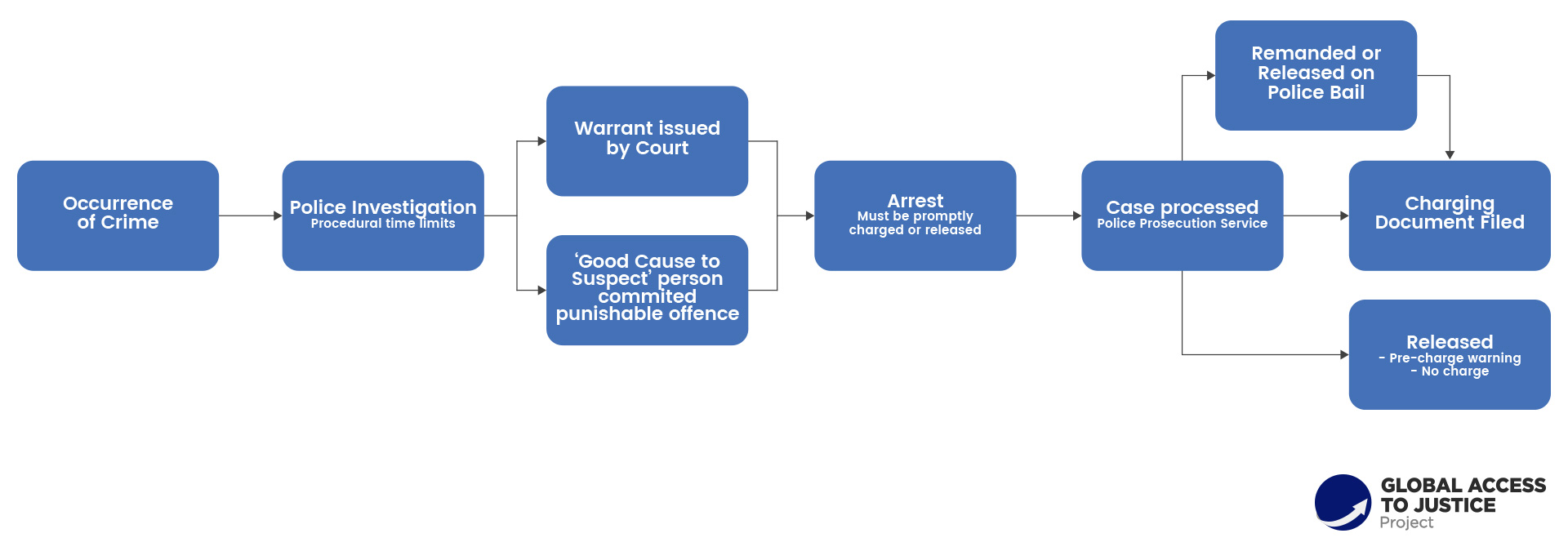

The steps of investigations are set out in Chart 04 (below). The authority responsible for criminal investigations is the New Zealand Police. New Zealand is served by one national police force which has 12 districts. The Police have eight functions including law enforcement.

The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (the NZBORA) sets out a person’s basic rights and freedoms that must be acknowledged by any person or body carrying out a public function, power, or duty. Section 22 of the NZBORA states that “everyone has the right not to be arbitrarily arrested or detained”. Although the NZBORA is not an entrenched constitutional document, other Acts cannot act contrary to a person’s rights under it. This means that police cannot detain any person if: they do not have a legislative power; it is unreasonable or unnecessary; or detention has continued for an unnecessarily long time.

The police have various powers to arrest a person. Arrest warrants may be issued by a court (e.g. for breach of bail condition or for non-appearance at a court hearing) and the police can then execute that warrant and arrest the person. However, in New Zealand, most arrests happen without a warrant. A person can be arrested if they are found committing an act that is a punishable offence (Crimes Act 1961, s 315(2)(a); Summary Offences Act 1981, s 39(2)), or the police have “good cause to suspect” that a person committed a punishable offence (Crimes Act 1961, s 315(2)(b); Summary Offences Act 1981, s 39(1)). Police officers are required to consider a wide variety of criteria in determining whether or not to arrest without warrant. “Good cause” does not need to be evidence which would be legally admissible in court; just a basis for reasonable suspicion. The police may have gained good cause to suspect from a number of sources including their own observations, statements from witnesses, admissions from the offender, examination of the scene, or forensic evidence.

Once a person is arrested, they must be informed of their rights under s 23 of the NZBORA. There is no prescribed wording, but the person must be told the reason why they are being detained, of their right to remain silent, and of their right to consult and instruct a lawyer without delay. The arrested person must then be promptly charged and either brought before a court or released (being released includes: released on police bail under s 21 of the Bail Act 2000, released with a pre-charge warning, or released without charge). The use of the word ‘prompt’ acknowledges that some time will pass between charge and court appearance, but an officer cannot delay bringing an arrested person before a judge in order to facilitate a police investigation.[1] A lawful arrest can become an unlawful arbitrary detention because of the circumstances and length of detention.

A person who has committed a punishable act may alternatively be brought before the court by way of a summons (i.e. without loss of liberty through arrest). Under this method, a summons is served on the person, which explains the nature and particulars of the charge they face. The summons will also include the date which the person must appear in court, which must be no later than two months after the summons is served (Criminal Procedure Act 2011, ss 28-30).

Section 25 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2011 sets out the procedural time limits for investigating a crime by way of setting time limits for commencing prosecutions. A charging document, which initiates criminal proceedings in court and effectively concludes the investigation, must be filed within certain time periods for different types of offences. Offences in New Zealand are classified as Category One (lower-level offending) through to Category Four (serious offending). There is no time limit for filing a charging document alleging the commission of a Category Four offence, but there are limits for the other categories, which will depend on the maximum penalty. For example, where the maximum penalty is imprisonment for three years or less, the charging document must be filed within five years after the date on which the offence was committed. Time limits may also be set by the particular statutes which govern certain offences.

Chart 04. Main steps of the criminal investigation phase

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

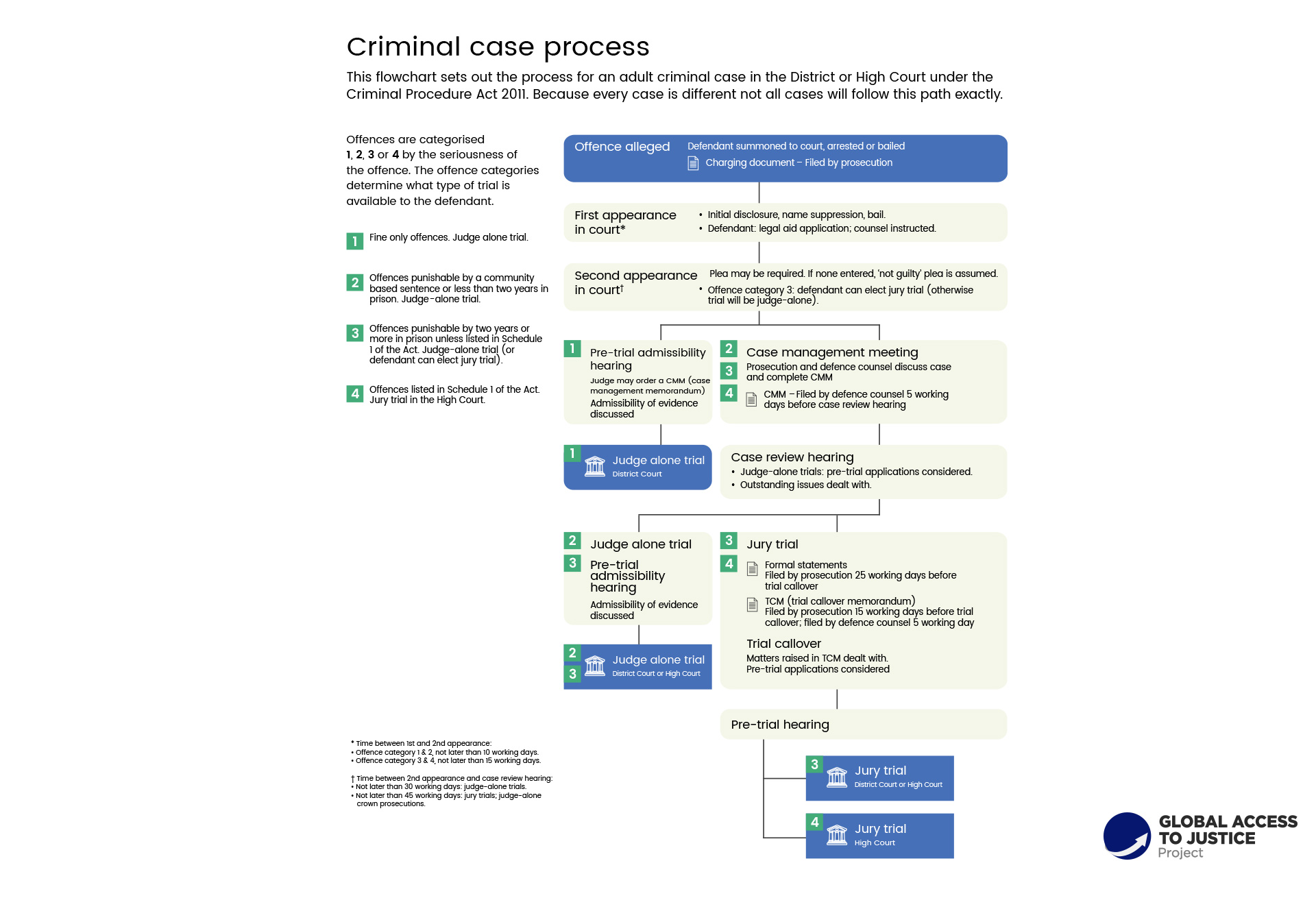

The Criminal Procedure Act 2011 governs the procedure for criminal cases, which begins with the filing of a charging document with the Court. Section 15 of the Act states that “any person may commence a [criminal] proceeding” by filing a charging document in the District Court. Private prosecutions are allowed in New Zealand, but are subject to independent judicial oversight (for example, see Turner v South Taranaki District Council [2015] NZHC 1869) and in practice are rarely brought. The majority of prosecutions are initiated by the Police Prosecution Service, who will file the charging document. The Police Prosecution Service conduct the proceedings for most Category 1-3 offences and traffic offences. Crown Solicitors, who are appointed by the Governor-General, assume responsibility for more serious offences (e.g. Category 4 offences).

Quasi-criminal/regulatory offences, for example breaches of workplace safety requirements or environmental legislation, or breaches of council bylaws, may be prosecuted by in-house prosecution teams of lawyers employed by the government agencies that administer the particular legislation. Crown Solicitor’s firms or private law firms may also prosecute these matters on instructions from the relevant agencies. For example, WorkSafe New Zealand is a branch of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), which investigates and prosecutes breaches of the Health and Safety in Employment Act 2015. Prosecutions of offences under this Act are conducted by lawyers employed by WorkSafe. On occasion where the matter is particularly complex WorkSafe may instruct a lawyer in private practice, a barrister, or a crown solicitor to act.

Prosecutors have discretion to withdraw a charging document at any time up to a finding of guilt/entry of a guilty plea. The Police Adult Diversion Scheme applies to non-serious offences where the prosecutor considers that it would be appropriate to deal with the charges without going to court. The scheme provides scope for the prosecutor to punish the offender without the offender receiving a conviction. The offender must accept full responsibility for the offence, and agree to the terms of the diversion, e.g. payment of money to a charity or to the victim to recognise property damage or emotional harm, apology to victim, attending addiction treatment or other therapeutic programmes.

Other ways of informally resolving criminal cases include a formal warning system and plea negotiations[2]. There is pressure on prosecutors to reach plea bargains as a way to avoid trial and therefore save money and suggestions that defence lawyers are incentivised by low legal aid payments to promote guilty pleas[3].

Once the defendant has been charged, they appear in District Court for the first appearance hearing. At that hearing, bail will be considered under the Bail Act 2000. For any offences where the maximum punishment is less than three years imprisonment (with some exceptions), the defendant is bailable as of right. Sections 7 and 8 of the Bail Act 2000 provides that defendants who are not bailable as of right must be released on reasonable terms and conditions, unless the court is satisfied that there is just cause for continued detention (e.g. a risk that the defendant may fail to appear in court). The court will also consider any application for name suppression. The defendant will be given information about legal aid (see section 5 of this report) and can instruct counsel if they have not already done so.

At the first appearance, “initial disclosure” is provided to the defendant by the prosecutor. “Initial disclosure” is documents that, inter alia, fairly inform the defendant of the fact on which it is alleged that an offence has been committed and the facts alleged against the defendant (Criminal Disclosure Act 2008, s 12).

Defendants may be ready to enter a plea at their second appearance, depending on whether they have had sufficient opportunity to consider initial disclosure. For certain offences, the defendant will also have to elect whether to proceed to a judge-alone trial or a jury trial.

If the defendant pleads not guilty, the case proceeds to trial. The majority of criminal trials take place in the District Court. Serious offences are transferred to the High Court. The location of the hearing is usually determined by where the charge was filed, but a hearing may be transferred to another location if necessary.

The procedure and timelines that follow the second appearance hearing will depend on the following factors: the category of offence, the court that charge will be heard in, and whether the trial will be judge-alone or a jury trial. Chart 05 from the Ministry of Justice outlines this process.

3.1.3. Absentia

Defendants are generally entitled to be present for any hearing in court that is related to the charge (Criminal Procedure Act 2011, s 117(1)). This does not have to be physical presence. There is now a presumption towards audio-visual links for all criminal procedural matters when the defendant is in custody and audio-visual links can also be used during sentencing (see s 8 Court (Remote Participation) Act 2010). New Zealand has relatively few prisons spread across its two main islands and audio-visual court appearances reduces the need for prisoner transportation.

This right to be present for proceedings is not absolute. Section 117(2) of the Criminal Procedure Act 2011 allows for the defendant to be removed from the proceedings if they are disruptive and risk prejudicing themselves to the jury. If possible, the Judge will try to facilitate involvement in the proceedings using other methods (e.g. audio-visual links). In certain proceedings, a defendant can also ask for leave from the judge to be absent (see s 117(3) of the Criminal Procedure Act 2011). When defendants are removed from the courtroom, the trial proceeds via the defendant’s legal counsel. In the very rare cases where section 117 applies to a self-represented defendant the trial carries on with amicus curiae appointed to assist the court to ensure the defendant receives a fair trial (see R v Tully, CRI-2014-009-008232, 24 February 2016 (HC)).

Chart 05. Main steps of criminal prosecution proceedings

Source: Ministry of Justice: <www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/MOJ0100.3C-At-a-glance-factsheet-AUG19.pdf>

Source: Ministry of Justice: <www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/MOJ0100.3C-At-a-glance-factsheet-AUG19.pdf>

3.1.4. Consistency with the Rule of Law & Due Process

New Zealand highly values the rule of law and respects due process. The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index (2019) ranks New Zealand as number 8 (score of 0.82) out of 126 countries for adherence to the rule of law. When looking more specifically at the criminal justice system, New Zealand is ranked number 13 (score of 0.72) out of 126 countries.

New Zealand is a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and has made a commitment to uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and support the efforts of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

In the 2014 Universal Periodic Review by the UN Human Rights Council, New Zealand was praised for its human rights record and has a reputation as a comparatively fair and equal society. New Zealand was criticised, however, for the over-representation of Māori and Pasifika in the criminal justice system. It was recommended that New Zealand establish national strategies that will address structural discrimination in the justice system. New Zealand has implemented a number of actions which are addressed in the Human Rights Council’s 2019 National Report[4]. The 2019 Report recognises that while some positive initiatives have been implemented, and advances made, work to address iniquities faced by Māori and Pasifika needs to be ongoing.

3.2. Civil Procedure

3.2.1. Jurisdiction

Ordinary civil cases in New Zealand are heard in either the High Court or the District Court at first instance. The High Court’s jurisdiction is largely conferred by statute, but it also has inherent common law jurisdiction (the only New Zealand court with inherent jurisdiction). In its civil jurisdiction, the District Court may hear claims up to a value of $300,000. Disputes of less than $30,000 may be heard in the Disputes Tribunal rather than the District Court. Pursuant to section 78 of the District Court Act 2016, the District Court does not have jurisdiction to hear disputes regarding the recovery of land (with some exceptions – see s 79 District Court Act 2016), proceedings relating to Crown prerogatives, or the interpretation or validity of wills. Applications for judicial review are limited to the High Court (see s 8 of the Judicial Review Procedure Act 2016).

Specialist jurisdictions – including the Family Court, the Environment Court, and the Employment Court – hear cases concerning specific legislation, under which those courts are constituted. For example, the Environment Court is constituted under the Resource Management Amendment Act 1996, and the Employment Court and its predecessors have their foundations in the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1894 and are now governed by the Employment Relations Act 2000.

Appeals from decisions of the District Court are heard in the High Court, and then may be appealed further to the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court. High Court appeals are heard by the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. An appellant must apply for leave to appeal to an appeal court of second instance.

3.2.2. Procedural rules

The High Court’s practice and procedure is regulated by the High Court Rules 2016 (the High Court Rules), pursuant to s 146 of the Senior Courts Act 2016. The High Court Rules are subject to the Senior Courts Act 2016 and the Evidence Act 2006 (and other statutes and regulations where applicable). High Court Rule 1.2 states the Rules’ objective: “to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of any proceeding or interlocutory application”. This, and the Court’s inherent jurisdiction, allows for flexibility of procedure where that is necessary. The District Court Rules 2014 (the District Court Rules) govern procedure for the District Court. They allow for the High Court Rules to be followed in circumstances where there is no other set procedure.

The High Court Rules and the District Court Rules, and those of the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, are written by the Rules Committee, which is a statutory body established by s 51B of the Judicature Act 1908 (now repealed) and its replacement statute, the Senior Courts Act 2016 (see s 155 of that Act). The Rules Committee comprises the Chief Justice, the Chief High Court Judge and the Chief District Court Judge, the Attorney-General, the Solicitor-General, the Chief Executive of the Department for Courts, two High Court Judges, one District Court Judge, and two lawyers. The Committee relies heavily on input from judges, lawyers and other interested people. To discharge its rule-making functions, the Committee may also undertake consultation, publicise proposed and enacted rule changes and assist with educating about new rules.

3.2.3. Trial procedure

Civil matters are determined by the fact-finder applying the civil standard of proof where facts are proved on the balance of probabilities, i.e shown as more probable than not. The civil standard of proof is not defined in legislation. Z v Dental Complaints Assessment Committee [2008] NZSC 55 includes an analysis of the law regarding the civil standard of proof in New Zealand at [94] – [112] with the Supreme Court concluding: “there is accordingly a single civil standard, the balance of probabilities, which is applied flexibly according to the seriousness of matters to be proved and the consequences of proving them” (at [112]).

Civil trials in the High Court are heard before a judge alone unless they concern defamation, false imprisonment, or malicious prosecution, in which case any party to the proceeding may require it be tried by a High Court Judge with a jury (High Court Rule 16). All matters in the District Court other than those governed by the Criminal Procedure Act 2011 are heard before a Judge alone, who determines all questions of fact and law (District Court Act 2016, s 108).

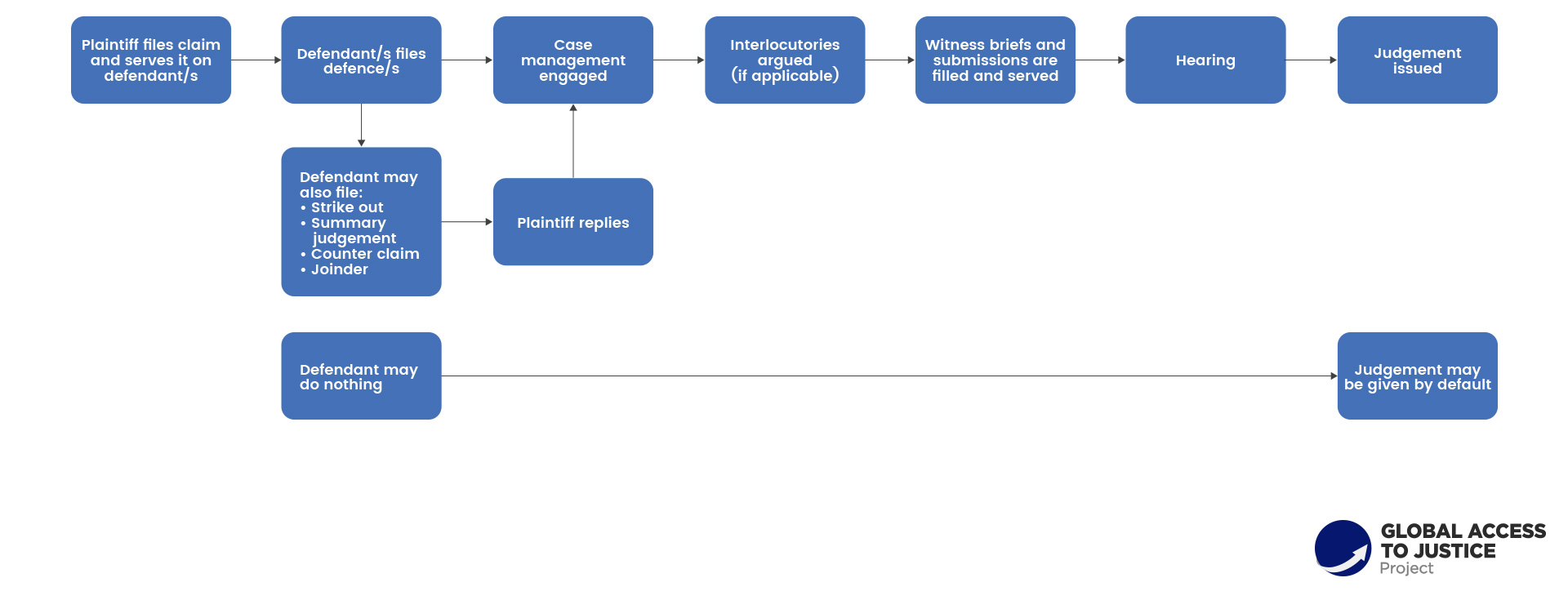

The process of a civil trial is summarized in Chart 08 (below). Civil proceedings are commenced by filing a statement of claim in the relevant registry of the Court. The proceedings are served on the defendant, accompanied by ‘initial disclosure’, which in the civil context are the key documents the plaintiff relies on to establish their claim (initial disclosure documents are not filed in the Court). Once the defendant has filed their statement of defence, the matter is set down for an initial case management conference before a judge. Court rules set out the issues to be agreed/ordered at the conference, and it is expected that the parties will have conferred and, where possible, agreed to these issues prior to the conference. Evidence is not heard at case management conferences. The conferences are often heard by way of teleconference which can result in time and cost savings, as lawyers do not have to travel to Court. Represented litigants are not required to attend case management conferences.

If the parties can agree on issues to be determined at a case management conference, the judge may take a relatively passive role confined to formalising orders required. If the parties cannot agree on issues, the judge will hear submissions from counsel and make appropriate orders. At any case management conference the judge may give directions to secure the “just, speedy and inexpensive determination of the proceedings” (High Court Rule 7.2(3)).

Once the parties have exchanged discovery documents and any interlocutory matters have been dealt with, the matter is allocated a hearing date. If further case management conferences are required, they may be held at any time either on the judge’s initiative or on the application of one or more parties (High Court Rule 7.2).

It is common practice for evidence in civil proceedings to be given by way of written brief, which are exchanged between the parties prior to the hearing. The witness then reads their brief in Court, and is cross-examined by the other party’s lawyer. Judges may question witnesses directly. A judge may adjourn a matter for further evidence to be filed, if that becomes necessary.

3.2.4. Shortened trial procedure

The rules of procedure allow for litigants to apply for summary judgment in cases where either the defendant has no defence, or the plaintiff’s cause of action cannot succeed. Summary judgment proceedings are heard on an interlocutory basis, with evidence given by affidavit. If the application for summary judgment is unsuccessful, then the matter may be set down on the ordinary track to proceed to a full trial. Summary judgment proceedings can be dealt with more efficiently (in terms of time and money) than other proceedings.

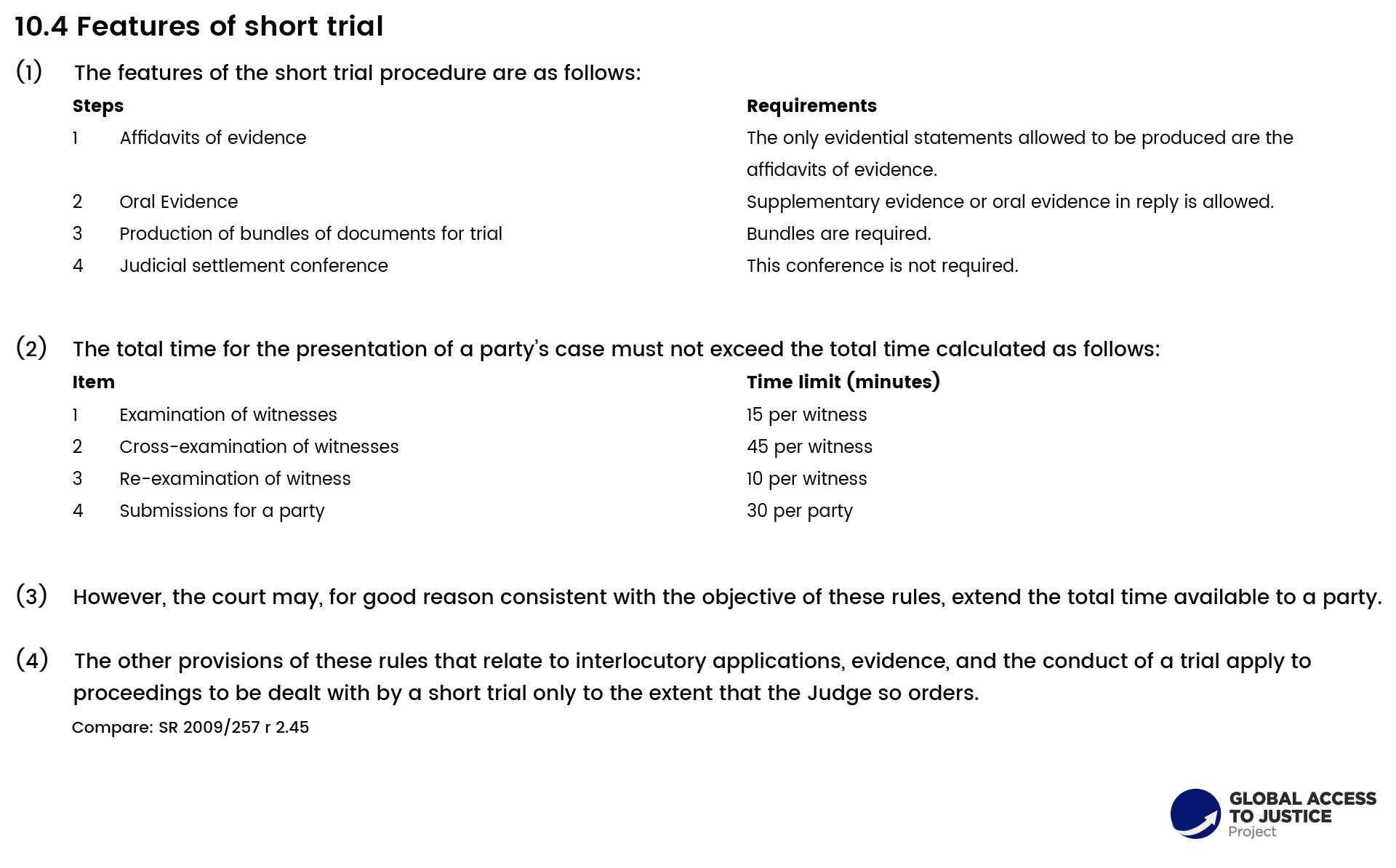

In the District Court, civil proceedings are allocated either a “short trial”, a “simplified trial” or a “full trial” when they are filed. These trial allocations may be changed at any point. District Court Rule 10.1(3) provides that the short trial is intended for claims where the court considers that 1 or more of the following apply:

(a) the case can come to a hearing quickly;

(b) the issues are relatively uncomplicated or a modest amount is at stake;

(c) the trial time is not likely to exceed a day.

The features of a short trial are summarised in Rule 10.4, presented in Chart 06.

Chart 06. District Court Rule 10.4: Features of short trial

Pursuant to District Court Rule 10.1(4), the simplified trial is intended for claims where the court considers that 1 or more of the following apply:

Pursuant to District Court Rule 10.1(4), the simplified trial is intended for claims where the court considers that 1 or more of the following apply:

(a) the duration of the hearing is not likely to exceed 3 days;

(b) there is some complexity raised by the issues;

(c) the amount of money involved is more than modest;

(d) 1 or more expert witnesses will be giving evidence.

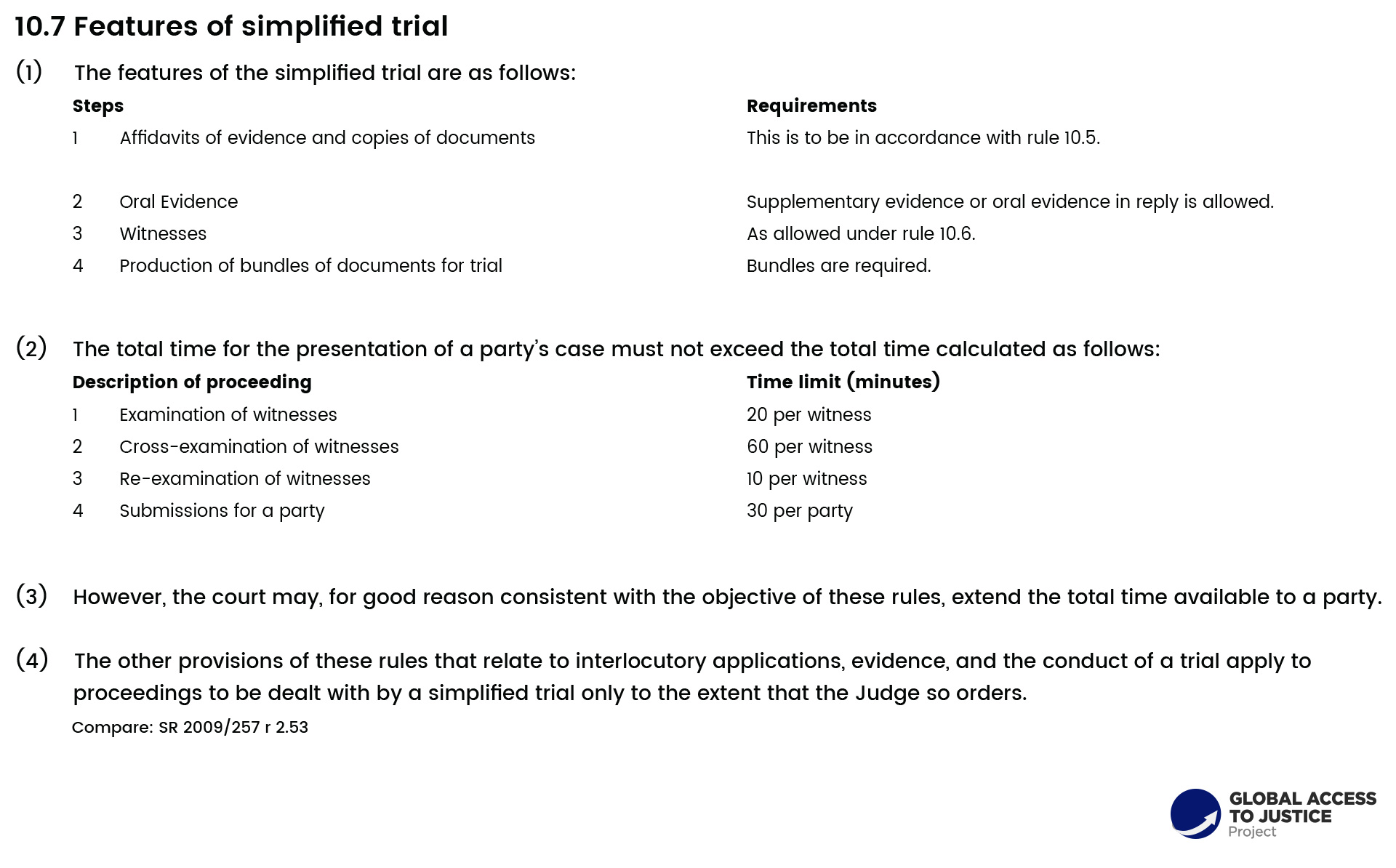

The features of a simplified trial are set out in Rule 10.7, presented in Chart 07.

Chart 07. District Court Rule 10.7: Features of simplified trial

Chart 08. Main steps of the first instance civil trial procedure

Chart 08. Main steps of the first instance civil trial procedure

3.2.5. Unrepresented litigants

3.2.5. Unrepresented litigants

Litigants are entitled to appear in New Zealand’s courts without representation by a lawyer. The Ministry of Justice website provides some basic information for litigants in person[5]. Where unrepresented litigants appear in civil proceedings, judges may (or may not) offer them limited assistance by explaining procedural steps, or by ignoring defects in the form of documents. At all times, a judge must be impartial, so any assistance given to a litigant in person will be limited.

3.2.6. Management of urgent matters

If a matter requires urgent determination, because, for example, there is immediate risk of dissipation or destruction of property, or damage to a person’s interests (for example imminent publication of a defamatory statement or breach of copyright) the rules of procedure allow for interlocutory injunctions to be sought (see High Court Rules 7.53-7.58 and District Court Rules 7.45-7.50). An interlocutory injunction will restrain a party from acting in a particular way (or compel a party to do something) until such time as the plaintiff’s claim can be heard and determined at a full trial. Applications for interlocutory injunctions can be made without notice (ex parte) pursuant to High Court Rule 7.23 and District Court Rule 7.16 if the applicant can show that proceeding on notice will, inter alia, cause undue delay or prejudice. High Court Rule 7.54 and District Court Rule 7.46 require an applicant for an interlocutory injunction to file a signed undertaking that the applicant will comply with any order for the payment of damages to compensate the other party for any damage sustained through the injunction.

If parties consider a civil matter requires swift disposition but the test discussed above cannot be met, they can raise this at the first case management conference. Requests to have a matter heard quickly can sometimes be accommodated if the parties are able to travel to a different Court location, or can otherwise be flexible.

Other courts may also have provisions in their relevant legislation that allow for urgent determinations. One such court where urgent matters are frequently heard is the Family Court, where orders (usually temporary or interim) can be made on a without notice basis; that is, without the other party being heard. These urgent applications should only be made in emergency situations where the applicant can show that the time needed to let the other party respond could lead to serious injury, undue hardship, a risk to personal safety (of the applicant or their child), or child being removed from New Zealand.

3.2.7. Encouraging settlement during formal proceedings

In the District Court, unless a short trial is to be held, cases must be referred to a Judicial Settlement Conference (JSC) prior to being set down for trial. The purpose of a JSC is to give the parties to the proceeding an opportunity to negotiate a settlement of the claim or any issue. A JSC is convened by a District Court Judge, and its proceedings are confidential to the parties and their legal advisers. A Judge who convenes a JSC may assist the parties in their negotiations, but that Judge must not preside at the trial (if any eventuates) unless all parties taking part in the conference consent, or the only matter for resolution at the hearing is a question of law. At least ten working days prior to the JSC, the parties must file and serve on the other parties copies of their “will say” statements which set out the evidence the parties rely on and a memorandum identifying the issues and any settlement negotiations. These documents are not admissible at any trial of the proceeding. If the Judge assisting the parties at a JSC is satisfied that the parties are unable to settle the claim or issue, the Judge must, as soon as practicable, indicate that he or she has formed that view, and adjourn the proceeding to a second case management conference.

In the High Court, JSCs are not compulsory. There is informal encouragement to settle through the use of negotiation or mediation and judge-led settlement is available in limited cases[6]. At the first case management conference the question of whether a matter is suited to private mediation will also have been discussed. High Court Rule 7.79(1) provides that a Judge may:

… at any time before the hearing of a proceeding, convene a conference of the parties in chambers for the purpose of negotiating for a settlement of the proceeding or of any issue, and may assist in those negotiations.

New Zealand also has examples of innovative procedure to both maintain a separate judicial process while facilitating settlement. This can be seen in the process developed in response to the Canterbury earthquake sequence (2010-2011), which caused significant property damage giving rise to many claims (the earthquakes also caused loss of life but claims for personal injury are barred by statute, see 3.4 below). A procedure was introduced streamline the judicial processing of these cases while creating transparency about the claims in order to facilitate settlement[7].

We are not aware of any empirical research into the fairness (or otherwise) of JSCs or other incentives to settle within the court process. JSCs are private to the parties pursuant to the provisions of the court rules. Anecdotal evidence suggests that settling matters prior to trial results in reduced costs for the parties but that power imbalances may also create unfair settlements in some circumstances.

3.2.8. Consistency with the Rule of Law

New Zealand highly values the rule of law and respects due process. The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index (2019) ranks New Zealand as number 8 (score of 0.82) out of 126 countries for adherence to the rule of law, and 11 out of 126 for civil justice.

The index scores New Zealand at 0.75 for “no unreasonable delay”. Delay in the civil high court system has been the subject of research conducted by the University of Otago Legal Issues Centre[8]. This was the first major New Zealand study to investigate the pace of High Court civil cases and to examine if and when delays might occur. The study report concluded that while delays are a key obstacle in accessing justice, there are varied reasons as to why delays occur, and how they impact on participants in the justice system – not all delays are negative. The study also concluded that further data collection and analysis is required before reforms addressing delay can be implemented.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

New Zealand’s use of ADR is part of the wider trend in common law countries, with New Zealand following closely the developments in the United States and Australia from the 1980s onwards. The impetus for ADR was driven by the same factors in other common law countries: “Court overload, high litigation costs, social changes and subsequent challenges to traditional approaches of resolving disputes led to calls for mediation, conciliation and negotiation to supplement, and even replace, adversarial litigation”[9]. Inclusion of conciliation and mediation was mostly state-led from the 1980s with the inclusion of over 30 statutory references through the 1980s and 1990s[10]. There are now references to ADR processes across a wide range of New Zealand legislation. As commentators summarised:

The growing awareness of ADR is apparent from New Zealand’s legislative history. … By way of some examples, the Local Government Act 2002 at s 16 sets out a process for mediation if significant new activities are proposed by the regional council and agreement is not reached with the affected territorial authorities. The Weathertight Homes Resolution Services Act 2002 sets out a prescriptive process for the mediation and adjudication of claims (at ss 13 to 55). The Legislative Advisory Committee lists over 40 other examples in a range of areas including Maori fisheries, environmental law, Maori land law, family law and many others.[11]

Given the large number of government ADR schemes, there is now a Government Centre for Dispute Resolution which is tasked with developing best practice dispute resolution guidance, as well as advising on design, development or improvement of schemes.

Mediation in employment law is “quasi-mandatory” as both the Employment Relations Authority (the body that hears first instance employment disputes) and the Employment Court have a duty to direct parties to mediation (Employment Relations Act, ss 159 and 188)[12].

Parents and guardians who take disputes about children to the Family Court are expected to have attempted to resolve the dispute themselves with the help of the Family Dispute Resolution mediation process (FDR), with a hearing in front of a judge being seen as a resort only where alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is impossible (Care of Children Act 2001 s46E, Family Dispute Resolution Act 2013). This mediation service is provided by registered, private parties. If a person applies to the court regarding a dispute about children, they must usually also have attended a “Parenting Through Separation” course. The course comprises four one-hour long sessions and is provided for free by the Family Court. Until March 2014, the Family Court provided free counselling and mediation services in all cases. Those services were replaced by the FDR process, which is offered free to those whose income is below a certain threshold.

There has been some criticism of the FDR process. An independent panel was appointed to examine the 2014 family justice reforms, and the final report was published in May 2019[13]. In relation to FDR the panel found that while around 84% of completed mediations since 2014 had resolved some or all issues 40% of people had refused to engage with FDR “because they simply did not want to do FDR”[14].

New Zealand has also established specific ADR schemes for particular purposes. For example, in an effort to resolve outstanding claims arising from the Canterbury earthquake sequence, the government established the Greater Christchurch Claims Resolution Service. It provides “free facilitation and determination services and access to engineering, legal and well-being support” tailored to individual homeowner needs[15]. Homeowners can still access the courts but this service is established to settle claims without the need to resort to the courts.

Outside these contexts, ADR processes are often triggered by the inclusion of dispute resolution provisions in contracts. These often appear as tiered processes, for example direct negotiation followed by mediation followed by arbitration. Mediators and arbitrators appointed as a result of these contractual terms may be via government schemes or by private arrangement. As most ADR schemes are mediation based, there are no appeal rights (given decisions are by agreement, not adjudication).

Commercial entities contract with government agencies to provide ADR services. One example is FairWay Dispute Resolution Limited (FairWay). FairWay was initially conceived as an arm of the Accident Compensation Corporation (see section 3.4 below) before becoming an independently owned company that provides dispute resolution services across a wide range of public and private entities. FairWay’s website states that it employs over 100 staff and contracts with over 110 specialist reviewers and dispute resolution practitioners, and handles over 16,000 cases per year[16].

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

A major feature of the New Zealand legal system is its no-fault accident compensation scheme. Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) provides insurance for all personal injury and came into being in 1972. Taxpayers, employers, self-employed people and motor vehicle owners to pay a levy to ACC to fund the scheme[17]. Court actions cannot be brought to recover for loss for personal injury. This removes a large portion of cases that might otherwise be litigated in New Zealand courts or subject to alternative dispute resolution. ACC is not without its critics but it is thought to be cheaper and more efficient than litigating for personal injury: “An independent evaluation by PriceWaterhouseCoopers in 2007 found that the ACC scheme achieved a level of benefits and performance comparable with Australia and other countries, at a lower cost”[18].

New Zealand also has a no-fault divorce regime. The Family Proceedings Act 1980 (which came into force in 1981) removed the requirement to prove fault before a dissolution order was issued. The requirement for a hearing in front of a judge to gain a dissolution order was removed in 1990.

Claims under $30,000 are heard in the Disputes Tribunal which has an informal procedure (Disputes Tribunal Act 1988). Tribunal referees are not required to be legally qualified (although many are) and in the first instance try to bring the parties to a mutually agreed decision (Disputes Tribunal Act, s 18). If the parties cannot agree on an outcome, the referee will make a decision. The dispute is to be determined according to the substantial merits and justice of the case and in doing so the Tribunal is to have regard to the law, but is not bound to give effect to strict legal rights or obligations or to legal forms or technicalities (Disputes Tribunal Act, s 18).

There are very limited appeal rights from decisions of the Disputes Tribunal. There is a review process for ACC decisions but this has been the subject of criticism[19].

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

4.1. Statutory commitment to access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial

New Zealand does not have a written constitution that expressly provides for equal access to justice, but this right is protected by various provisions. For example, ss 25 and 27 of the NZBORA affirm that every person has the right to minimum standards of criminal procedure, which includes the right a fair hearing without delay, as well the right to natural justice, judicial review, and to take or defence civil proceedings involving the Crown. Similarly, the purpose of the courts’ procedural rules is to facilitate “the just, speedy, and inexpensive dispatch of the business” of the court as well as “the administration of justice” (Senior Courts Act 2016, s 145).

New Zealand is also a signatory to a number of international treaties that protect the right to justice and fair trial; including the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

4.2. Political commitment to access to justice

There is ostensibly political will by the current Government (who has governed since 26 October 2017) to improve access to justice. For example, the Attorney-General, the Hon David Parker (who is both a political and legal officer), recently commented on his concerns in the District Court:

The civil jurisdiction of the District Court has decreased to, largely, default and summary judgments. The reasons are complex but changes to District Court rules and processes are expected to be needed to reinvigorate this important function to enable more New Zealanders to cost-effectively resolve their disputes.[1]

The Ministry of Justice Statement of Intent 2018 to 2023 sets out the strategic intentions that will enable delivery of “people-centred services to provide justice for all”[2]. There are discrete projects underway to drive access to justice policy. For example, in May 2018 the Government pledged to increase spending on Community Law Centres by $2.2 million, a 20 per cent increase, to help stabilise funding and current service levels. This was followed a year later by an announcement locking in further funding of $8.72 million over the next four years. Other access to justice related initiatives from recent Government budgets include increasing the capacity of the Human Rights Review Tribunal by appointing deputy chairpersons to hear and determine more claims, and increasing spending on Youth Court capacity in response to changes in the youth justice system which allow 17 year olds to be dealt with there, instead of in adult courts. The Attorney-General has also called on the legal profession to help improve access by increasing the quantity of pro bono legal services provided to the civil market. To incentivise pro bono legal services, a lawyer’s commitment to improving access to justice is now a criterion for being selected as a Queen’s Counsel[3].

In 2019 the Ministry of Justice hosted a three-day criminal justice summit which was attended by more than 600 people from a diverse range of backgrounds. Victims, community advocates and people who have offended participated in a conversation alongside members of the judiciary, public sector officials and Members of Parliament. The structure of the summit was focused on co-design and partnership, with those who attended expected to participate and take ownership of a proposal to reform the criminal justice system. The summit was the “start of the conversation about what New Zealanders want their criminal justice system to look like”[4]. Further consultation will be undertaken by Te Uepū Hāpai I te Ora – The Safe and Effective Justice Advisory Group, which will provide advice to the Minister of Justice about a direction for the criminal justice system[5]. In March 2020, the Ministry of Justice hosted a one day civil justice summit, inviting key stakeholders from across the system and a report from that meeting will be published later in 2020.

4.3. Government oversight of access to justice

The Ministry of Justice is the Crown’s lead agency in the justice sector. It is the only agency in New Zealand’s public sector that works across all three branches of government and it is responsible for administering the court system, the legal aid system, and the Public Defenders Service (PDS). It also collects and enforces fines and civil debts, negotiates the settlement of historical Treaty of Waitangi claims and provides policy advice on matters related to justice, the administration of the law, and Crown/Māori relations. Information about the Ministry can be found on its website at <www.justice.govt.nz/about/about-us>. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment also has a justice portfolio, in that it oversees a large number of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms and is home to the Government Centre for Dispute Resolution (discussed further at 9.4).

There are various institutional practices that are designed to ensure that fundamental human rights are protected, including access to the courts. Mechanisms to review law and policy for consistency with human rights include:

(a) The Regulations Review Committee, which ensures that regulations are made lawfully;

(b) The Cabinet Office Manual, which requires any new law and policy to be assessed according to human rights;

(c) The Ministry of Justice and Crown Law Office, which have an obligation to review all draft legislation to ensure that it is consistent with the NZBORA. Section 7 of the NZBORA requires the Attorney-General to report any Bill that is inconsistent with any of the rights and freedoms contained in the Act to Parliament (this is limited to the introductory Bill, however, and not subsequent amendments).

4.4. Equal access to justice for minorities, immigrants, indigenous peoples or other groups

International bodies have criticized New Zealand’s protection of legal rights for those in marginalised groups. These groups include: disabled people; Māori and Pacific peoples; migrant communities; and children and young people. There is also concern about the disproportionate number of Māori in the prison system (see section 12.2 below).

4.5. Access to justice subject of public or scholarly debates

Access to justice is increasingly the subject of scholarly debate. The judiciary – who are frequently faced with the deficiencies in the justice system – have ignited debate through a series of confronting judicial speeches. In 2014, the then Chief High Court Judge, Justice Winkelmann, illustrated the growing justice gap in her speech titled “Access to Justice – Who Needs Lawyers?”, given at the 2014 New Zealand Law Foundation Ethel Benjamin Commemorative Address. Justice Winkelmann stated that access to civil justice is a significant challenge facing New Zealand. Reminding the profession that civil justice is a public good that is necessary uphold the rule of law, she stated that access must be prioritized and facilitated through innovative solutions[6]. Similar concerns about access to justice have since been echoed by the present Chief High Court Judge, Justice Venning[7], the Court of Appeal Justice Kós[8], and retired judge Ron Young[9].

The University of Otago Legal Issues Centre has been a leader in scholarly debate on civil access to justice[10]. The debate on civil justice has also reached the mainstream, for example a feature article in the national Sunday newspaper[11]. Access to justice in the criminal sphere is also a regular topic of debate in the media, with the national summit generating a lot of press coverage[12]. It is also the topic of scholarly debate with contributions from scholars in law, sociology, and criminology.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

The English procedure of in forma pauperis was introduced with colonisation in the 19th century but this was replaced by criminal legal aid in 1912 and civil legal aid in 1969. The civil and criminal schemes were merged by the Legal Services Act 1991. This Act had a partnership model with management of the scheme kept at arm’s length so that decisions about granting legal aid were, and were seen to be, free from political influence. The seeds were sown for significant changes to criminal legal aid with the first pilot of the Public Defenders Service (PDS) in 2004.

The cost of legal aid exploded between 2004 and 2010, climbing from approximately $80 million to approximately $152 million. A major review of the legal aid system was undertaken in 2009, resulting in significant changes to the administration of the legal aid system: Margaret Bazley Transforming the Legal Aid System: Final Report and Recommendations (Ministry of Justice, November 2009 (“Bazley Report”). The report was highly critical finding that a “small but significant proportion of lawyers [were] providing very poor services” and some were corrupt. A raft of changes were recommended including greater focus on customer service, greater control of lawyer standards, establishing more public defenders offices, as well as bulk funding other practices to provide low cost services. It was also critical of the Crown entity responsible for administering legal aid, the Legal Services Agency, and recommended it become part of the Ministry of Justice. Many of these recommendations were accepted and enacted via the Legal Services Act 2011, which currently governs the legal aid scheme. The changes aimed to significantly reduce the legal aid spend by introducing fixed fees for lawyer providers, user-charges for applicants, interest on legal aid debt, and strict eligibility criteria. Cuts were also achieved through expanding PDS, which now has over 150 criminal defence lawyers working from 10 offices around New Zealand.

During financial year 2018/19, the Ministry of Justice undertook a review of legal aid policy settings. The feedback was critical about the low rates of provider remuneration, low eligibility thresholds for civil and family legal aid, and the administrative burden on legal aid providers. No extra budget was allocated to address these issues and therefore no changes have been made.

Legal aid remains an important mechanism for providing access to the courts. However, the limits in its scope for civil and family (strict income thresholds and merits assessments for cases) mean that it provides limited support in achieving access to justice and equal access to court. As in other jurisdictions that have seen significant cuts to legal aid budgets, those who cannot afford private legal services but who are not eligible for legal aid are the largest part of the population[1].

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

The provision of legal aid is governed by the Legal Services Act 2011. Section 3 of that Act states that its purpose is to “establish a system to provide legal services to people of insufficient means [and to] deliver them in the most effective and efficient manner”.

Legal aid is considered the main mechanism for achieving access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial in criminal cases. The right to legal aid for criminal offences (where it is “in the interests of justice”) is protected by s 24(f) of the NZBORA which states:

Everyone who is charged with an offence shall have the right to receive legal assistance without cost if the interests of justice so require and the person does not have sufficient means to provide for that assistance.

There is no equivalent right for cases that do not involve a criminal offence. Civil legal aid is available in certain limited circumstances which we discuss below. There is income and asset testing as well as assessments of the merits of the case. Civil legal aid is not seen as a primary mechanism for achieving access to justice and equal access to the court in the civil system. Instead the primary mechanism has been self-representation. Lawyers are barred, except from some limited circumstances, from representing litigants in the Disputes Tribunal (for small claims) and the Tenancy Tribunal (for all residential tenancy cases). Lawyers are also barred from representing litigants in some parts of the Family Court process. Alternative dispute resolution via mediation and negotiation is also strongly encouraged (see section 3.3 above).

Section 18(2) of the Legal Services Act 2011 provides that every grant of legal aid is made subject to a condition that the aided person must make repayments. The amount to be repaid is set by the commissioner, and in some cases may be zero. In practice, civil legal aid is considered to be a loan, rather than a grant, as repayment of some or all of the grant will be sought in almost all cases.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

The Ministry of Justice now administers all aspects of legal aid in New Zealand. Most legal aid operates by providing funding on a case-by-case basis to registered lawyer-providers. The provision of criminal legal aid is, however, divided between funding of cases undertaken by legal aid registered criminal lawyers and funding to PDS. PDS is administered by the Ministry of Justice but operates largely independently from the Ministry, although is entirely funded by them, its website is hosted on <www.justice.govt.nz> and its lawyers are employees of the Ministry.

The Ministry of Justice also provides funding to the network of Community Law Centres throughout New Zealand. These Centres are independent entities that each have different funding models and provide different types of advice and advocacy services (for further discussion see 9.3.2 below). The Ministry funding is a core part of most Community Law Centre budgets.

5.4. Legal aid budget

Legal aid is a separate component of the annual Ministry of Justice budget. There are budget lines for the PDS and for legal aid, as well as for provision of funds to the Community Law Centres. The PDS budget for 2019 was NZ$35 million. The budget for funding of legal aid and Community Law was a combined NZ$205 million (approximately NZ$191 million for legal aid). There was also a budget of $31 million for administration of legal aid. The majority of the funding comes from the government, with some funding listed as being provided by “other”, which includes legal aid application fees charged to those seeking civil legal aid[2].

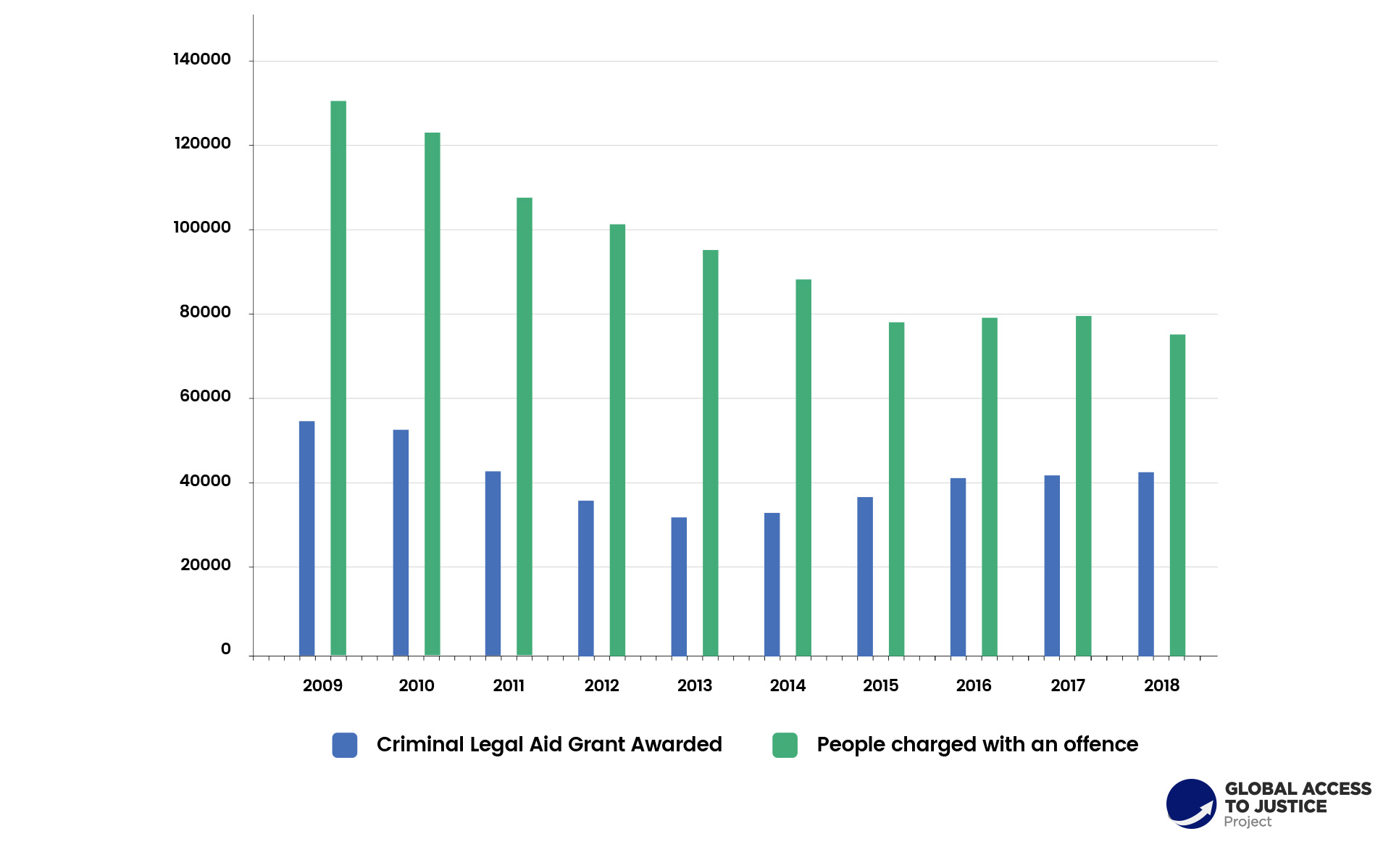

Legal aid expenditure on private legal aid providers peaked in 2009-10, declined through to 2013 and has risen steadily in the last five years (although still not to the level of the 2009-10 peak). The decline in funding post-2009 was driven by falling numbers of criminal legal aid grants (due to falling prosecutions), changes to the Family Court barring lawyers from appearing (number of family legal aid grants has fallen from 25,091 in 2010 to 17,788 in 2018), expansion of the PDS, and “changes to payment frameworks and new operational policies and procedures”[3].

5.5. Legal aid providers

Providers have to be an admitted lawyer in good standing and must prove they are a fit and proper person to provide legal aid. Providers are individually certified in specific listed areas of work (e.g. criminal, family, mental health) and must demonstrate their competence in the area for which they are certified. They are also certified by reference to the level of complexity of case they can undertake and the level of court that they may appear in. There has been a marked decline in the number of registered providers of legal aid since changes from the Bazley Report were implemented (for example, the number of civil providers halved). Reasons for this decline include low payment rates and the administrative burdens, both to register as a provider and to organise grants of legal aid and recoup payments.

Providers are paid in accordance with schedules which have fixed or hourly rates, depending on the work performed. The rates are much lower than those charged in the private market ($100-150/hour compared to fees two to three times more that in the private market). These rates have been criticized as being unsustainably low and the reason that many providers have not registered as legal aid providers. They also encourage lawyers to encourage quick resolution (even if that is not in the interests of the client) and also mean “inexperienced lawyers with insufficient time are trying cases”[4].

Providers performing legal aid work as independent practitioners have a high level of independence from the state. Criminal barristers have critiqued PDS as lacking independence from the Government (they are employees of the Ministry of Justice) and damaging the strength of the independent criminal defence bar[5].

5.6. Quality assurance

There is a strong legal aid quality assurance programme, possibly to the point of being over-zealous and creating burdens that have seriously limited the number of providers available to the public. Quality assurance includes initial approval for providers (outlined above), ongoing monitoring via an audit programme and complaints process, performance management, and requirements for re-approval.

Through a regular audit process, lawyers receive an audit rating, measured on a scale from one to five, with one being excellent and five being very poor. All New Zealand lawyers, including legal aid providers, are required to undertake continuing professional development as a condition of maintaining a practicing certificate.

Clients who are dissatisfied with the performance of their legal aid lawyer can use the complaints procedure. This is administered by the Ministry of Justice overseen by the Team Leader, Legal Aid Provider Services. Clients of the PDS service can also complain to the PDS. All clients can raise concerns about their lawyer with the NZLS’ complaints service, regardless of fee arrangement or who the lawyer is employed by.

5.7. Criminal legal aid

5.7.1. Scope of criminal legal aid

Criminal legal aid is available to people who are charged with, or convicted of, a criminal offence, and who cannot afford to pay for a lawyer to represent them in court (see Legal Services Act 2011, s 8, and NZBORA, s 24(f)). Criminal legal aid is available across the lifespan of a criminal matter – from arrest (irrespective of whether or not the person is remanded in custody) through to the trial, any appeals and parole hearings (Legal Services Act 2011, s 6). Criminal legal aid is not available for victims of crime. There is also no statutory requirement for witness costs (e.g. for travelling to court) to be met by criminal legal aid, but in practice this was regularly done by way of a pre-approved disbursement. The legal aid policy was revised in July 2019, and witness costs will now only be met in exceptional circumstances, with the amounts payable governed by the Witnesses and Interpreters Fees Regulations 1974.

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

Applicants do not have to be a New Zealand citizen or to be living in New Zealand permanently to be eligible for criminal legal aid. Eligibility is determined by the applicant’s financial circumstances, as well as by the seriousness of the offence, and whether it is in the interests of justice (Legal Services Act 2011, s 8).

Pursuant to s 8(1)(b) of the Legal Services Act 2011 criminal legal aid will only be granted if the applicant has insufficient financial means to fund their own legal counsel. To determine the applicant’s financial circumstances, both gross income and disposable capital (e.g. equity in own home, value of main car) will be assessed; this may also include an assessment of a spouse or partner’s financial circumstances.