Region Europe Nordic Countries

National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

Finland has a parliamentary democracy with a multiparty political system. The head of the government is the Prime Minister who heads the executive branch of the government, and the head of state, the President of Finland, is in charge of the country’s foreign policy. The Executive, Legislative and Judicial powers are set out in the Constitution of Finland. The Constitution is the basis of all legislation and iterates the executive power and functions of the government. It lays down the fundamental rules, values and principles of Finnish democracy.

The Prime Minister is elected by Parliament after the majority party or a coalition government comes to power subsequent to parliamentary elections. The Judiciary functions independently of the executive and legislative branches of the state. In addition to the parliamentary democracy, Finland has used referendums, such as a referendum held in 1994 to vote for joining the European Union. Under direct democracy initiatives, 50,000 citizen signatures can be submitted to the Parliament (Eduskunta/Riksdag) to introduce a new law, like the recent initiative to introduce aviation tax to reduce CO2 emissions. This was subsequent to new constitutional amendments in 2012, which introduced direct democracy initiatives where citizens can suggest law reform or the introduction of new laws.

Municipality residents (irrespective of their citizenship) also vote in municipal elections and Finnish citizens vote in EU elections.

Finland has two official languages – Finnish and Swedish – as per the Constitution. The realisation of linguistic rights is a fundamental right under Article 17 of the Constitution in Finland. By law, an individual has the right to receive service and public documents in Finnish or Swedish. This means that both citizens and non-citizens have the right to use Finnish or Swedish with public authorities. The Finnish Constitution also protects the linguistic rights of Sámi and Roma and recognizes them as minority languages. Under the Constitution, they have the right to maintain and protect their language and culture.[1] According to the available data, the number of persons with Finnish as a mother tongue are 4 835 778 (= n. 88%), persons with Swedish as a mother tongue are 288 400 (= n. 5%) and number of persons with Sámi as mother tongue are 1 995 (= n. 0,04%).

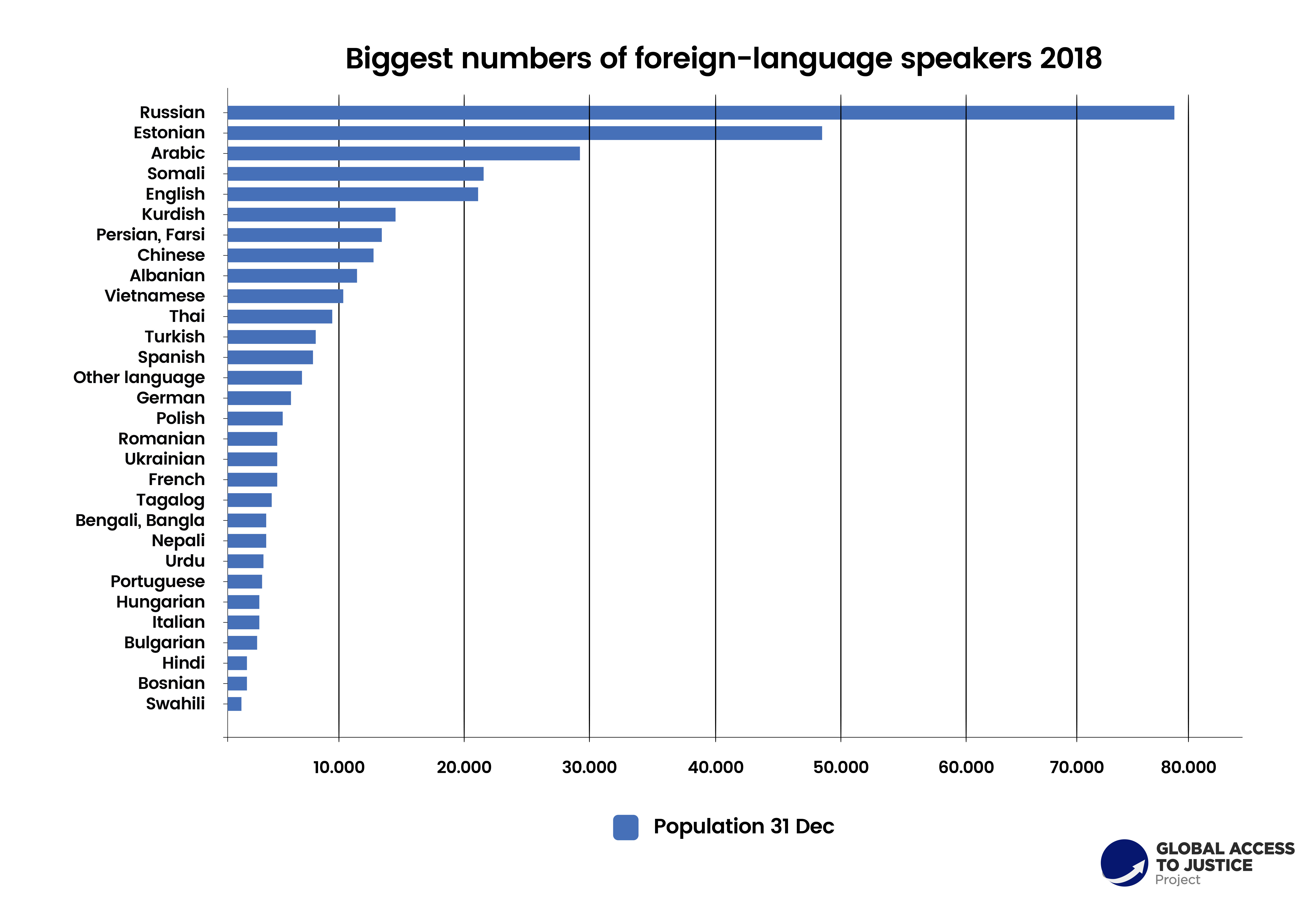

Other than Swedish and Finnish, the main other languages spoken in Finland are Russian, Estonian, Somali, English and Arabic. As for other minority languages spoken in Finland, Estonian, Arabic, Somali, English, Kurdish, Persian, Albanian, Vietnamese are spoken by 391 746 people (= n. 7%).

Chart 01. Biggest number of foreign-language speakers 2018.

Finland has a welfare system that provides its citizens with social insurance, social welfare, health care and employment protections of good working conditions. The Government and the municipality supervise the welfare and social schemes. As far as income security is concerned, Finland provides a national pension plan, employment pension, and sickness pension, unemployment insurance, disability insurance and workers’ compensation. Over and above that, Finland provides aid to families with children, childcare services and services for the disabled.

As of 2018, the Finnish population is 5.5 million. According to 2017 data, the average life expectancy at birth for boys was 78.7 years and 84.2 years for girls. The average expected year of schooling is 17.6 years and mean years of schooling is 12.4 years.

As per the UNDP Human Development Report on Finland, the 2018 Human Development Index (HDI) value is 0.925. This value positions the country at 12 out of 189 countries and territories studied.[2] The report further states that “between 1990 and 2018, Finland’s HDI value increased from 0.784 to 0.925, an increase of 18.0 percent.” This rise takes into account that life expectancy at birth increased by 6.5 years, mean years of schooling increased by 5.0 years and expected years of schooling increased by 4.3 years.

The IHDI (Inequality-adjusted Development Index) value for the country was 0.876 in 2018.

- Overall loss (%): 5.6

- Human inequality coefficient (%): 5.5

- Inequality in life expectancy at birth (%): 2.8

- Inequality in education (%): 1.9

- Inequality in income (%): 11.7

As per Statistics Finland’s 2016 income distribution data, the number of persons belonging to households at risk of poverty stood at 637,000.

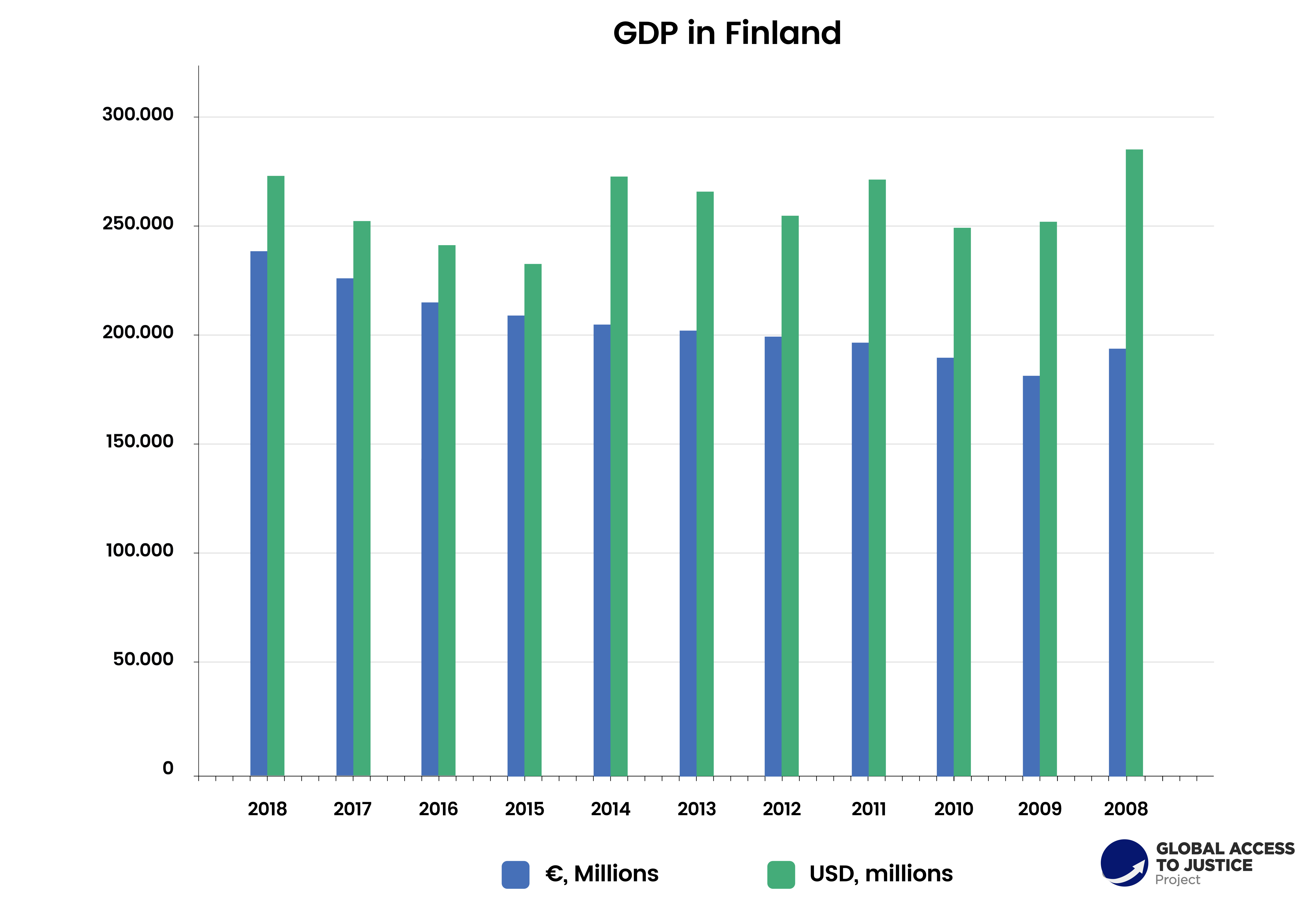

Chart 02. Gross domestic product (GDP) for the last ten years.

| Year | GDP millions € | GDP millions USD |

| 2018 | 233 555 | 274 210 |

| 2017 | 223 892 | 252 867 |

| 2016 | 216 073 | 239 106 |

| 2015 | 209 952 | 232 968 |

| 2014 | 205 474 | 273 043 |

| 2013 | 203 338 | 270 061 |

| 2012 | 199 793 | 256 854 |

| 2011 | 196 869 | 273 985 |

| 2010 | 187 100 | 248 244 |

| 2009 | 181 029 | 252 222 |

| 2008 | 193 711 | 284 870 |

Chart 03. Finland’s GDP in millions in euro and USD

The gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP) was 252 billion PPP US dollars in 2017.

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

Finland has a civil law tradition. The constitution of Finland lays down the rights, procedures and processes to be followed in enacting and implementing legislation. The judiciary is independent from the legislature and executive branches and judicial processes are governed by law and guaranteed under the Constitution. Courts are supervised by the Chancellor of Justice and the Parliamentary Ombudsman. In matters of law, the courts are independent. The Ministry of Justice does not supervise court decisions nor does it in any manner influence the functioning of the judiciary.

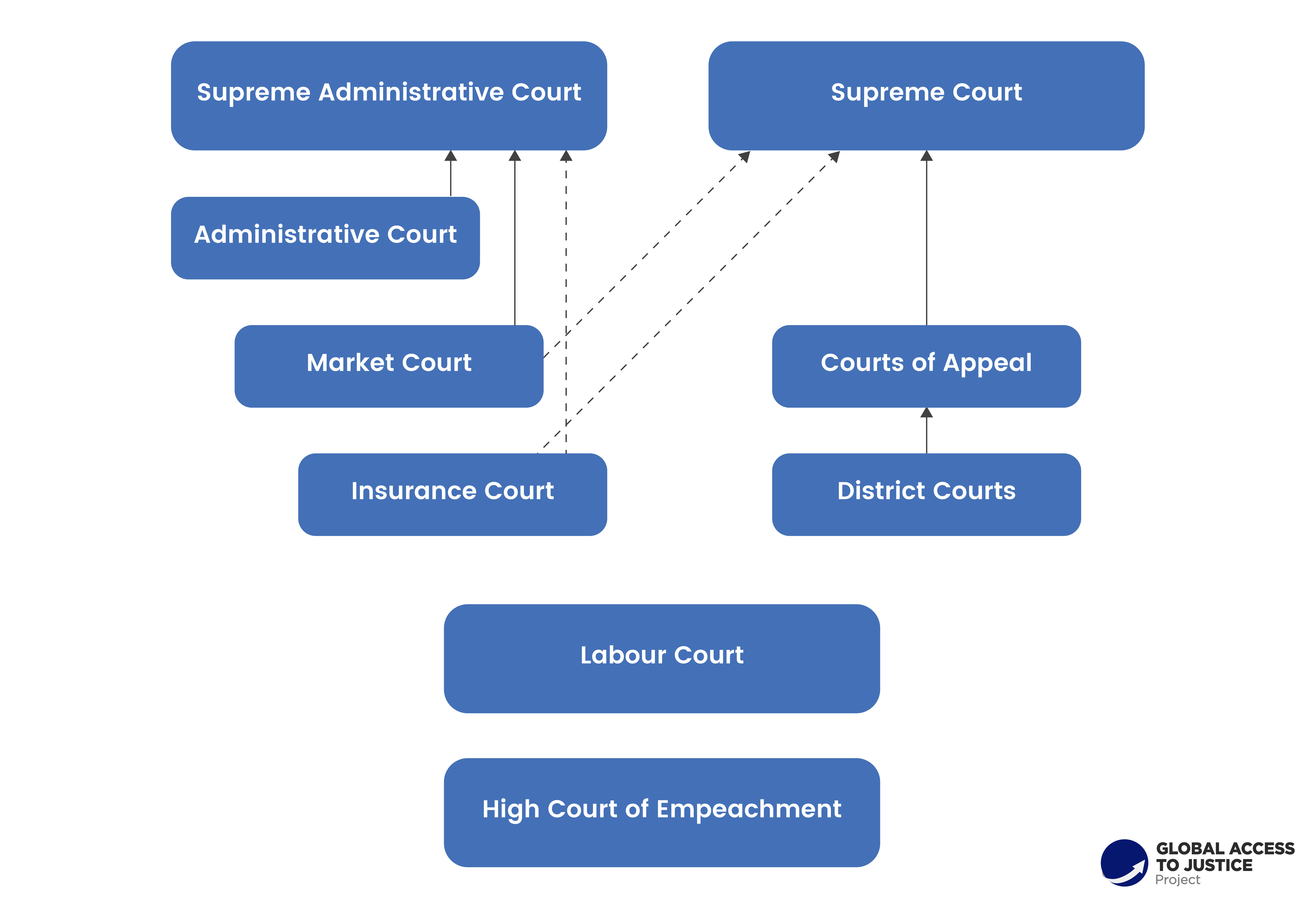

The court structure in Finland can be divided into:

- District courts

- Administrative courts, and

- Special courts

The district courts are courts of first instance, and deal with civil and criminal cases. The decisions made by the district courts may be appealed or challenged in the courts of appeal. Court of appeal verdicts can be challenged in the Supreme Court. There are administrative courts that review decisions of the authorities, and a Supreme Administrative Court. The higher courts monitor the lower courts.

Chart 04. Organisational Chart of the Justice System – Division of jurisdiction in Finland’s justice system.

There are also special courts set up under the law: the Market court, the Labour court, the Insurance court and the High Court of Impeachment. Proceedings in Finnish courts can be in either Finnish or Swedish.

A judge in Finland should have a university degree in law. Subsequent to the degree in law, a judicial traineeship at a District Court for a period of one year, as part of the general training exercise, is followed. They may thereafter work as a referendary[1] at a Court of Appeal or in an Administrative Court or may be temporarily employed as a District Judge. They may alternatively be appointed as a tenured judge at the Justice of a Court of Appeal or as an Administrative Judge. The training in various courts focuses on acquiring practical knowledge of the functioning of courts, procedures and legal knowledge in different cases.

Finnish judges are appointed by the President of the Republic on recommendation from the Minister of Justice and as advised by the Judicial Appointments Board. The Board is composed mainly of members of the judiciary, but three members must be from outside the judiciary: a practising lawyer appointed by the Bar Association, a prosecutor appointed by the Prosecutor General, and the third an academic appointed by the Ministry of Justice. As far as the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court is concerned, the courts have autonomy to submit their appointment proposals to the President, who is the final authority.

As a rule, the Board should recruit judges from diverse legal backgrounds including court referendaries, civil servants, academics and members of the legal profession.

As of 2018 the number of judges stood at 1068, with 485 male judges and 583 female judges. Judges are appointed until the retirement age of 68.

2.1. Legal structure

In Finland, the name for a lawyer is lakimies. The legal profession in Finland can be divided into:

- Lawyers who are members of the Finnish Bar Association (FBA) use the title asianajaja or advokat, which means attorney-at-law. To become a member of the Bar, a lawyer must be over 25 years of age, have a Masters’ degree in law, and a minimum of four years’ legal experience of which two years must be in a law office. Additionally, the lawyer must have passed the Bar exam.

- Public Legal Aid Attorneys are attorneys or lawyers employed by Public Legal Aid Offices (PLAO). They are appointed by the Minister of Justice and have to meet requirements for their appointment, such as a Master’s degree in law, experience of advocacy or adjudication, and many are also members of the Bar Association. They are supervised by the Bar Association irrespective of their membership and are expected to follow professional ethics laid down by the Finnish Bar Association. Finland has public legal aid offices throughout the country. As will be seen below, Public Legal Aid Attorneys are available in PLAO and private lawyers also can be used in legal aid cases provided that they are approved by the state legal aid services. State public legal aid is either free or partially funded by the state based on means testing and assessment of applicants. Public legal aid is available to citizens and non-citizens alike. This is discussed at length in later sections.

- A licensed legal counsel must hold a Master’s degree in law and should have relevant experience or pass the Bar exam, and must be authorised by the Finnish Bar Association Board. The license can be revoked in certain situations by the Bar Association.

The National Prosecution Authority (NPA) is the national prosecution body led by the Prosecutor General. It comprises the Office of the Prosecutor General, a central administrative unit, and five prosecution districts: Southern Finland, Western Finland, Eastern Finland, Northern Finland and Åland. The prosecution districts are responsible for carrying out prosecution activities. The NPA is led by the Prosecutor General of Finland and is under the Ministry of Justice.

Prosecutors handle criminal matters in Finland. The role a prosecutor plays starts from pre-trial investigation and continues through to court proceedings. Most prosecutors in Finland have court training. A person appointed as a prosecutor may initially be appointed as a temporary junior prosecutor for a period of six months, if he or she lacks the necessary training and experience. After the period of training, the prosecutor is inducted using a training programme arranged by the National Prosecution Authority. If prosecutors wish they can specialise in specific areas of crime, such as, financial crime or narcotics.

Prosecutors are appointed for life, that is, until the age of retirement (currently 68 years). As of 2017-2018, there are 372 prosecutors.

The key difference between the types of lawyers is that only advocates, public legal aid attorneys, prosecutors and counsel who have a license under the Licensed Counsel Act are permitted to practice in a court. The restriction does not apply to providing other kinds of legal services, such as legal counselling, drafting, or legal advice. There are restrictions on the services that an attorney-at-law can provide. A lakitoimisto/lakiasiaintoimisto (literally ’’legal office’’) can be owned by anyone, no matter his or her education. An asianajotoimisto (literally ‘’attorney-at-law office’’) can only be owned by a member of the Finnish Bar Association.

As of 2016, the total number of lawyers stood at 3,791. This includes 2,119 members of the Finnish Bar Association, 1,540 licensed lawyers and 229 public legal aid lawyers (97 public legal aid lawyers are also members of the Finnish Bar Association).

In Finland it is mandatory to use a lawyer at the Supreme Court in cases of extraordinary appeal (available after the decision has become final or on grounds specifically provided in law). The only exception is in cases concerning restoration of missed time limit. In cases where an application has been made to the Supreme Court for an annulment of a verdict or review of a judgment, legal representation is also mandatory. In all other courts, legal representation is not obligatory.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

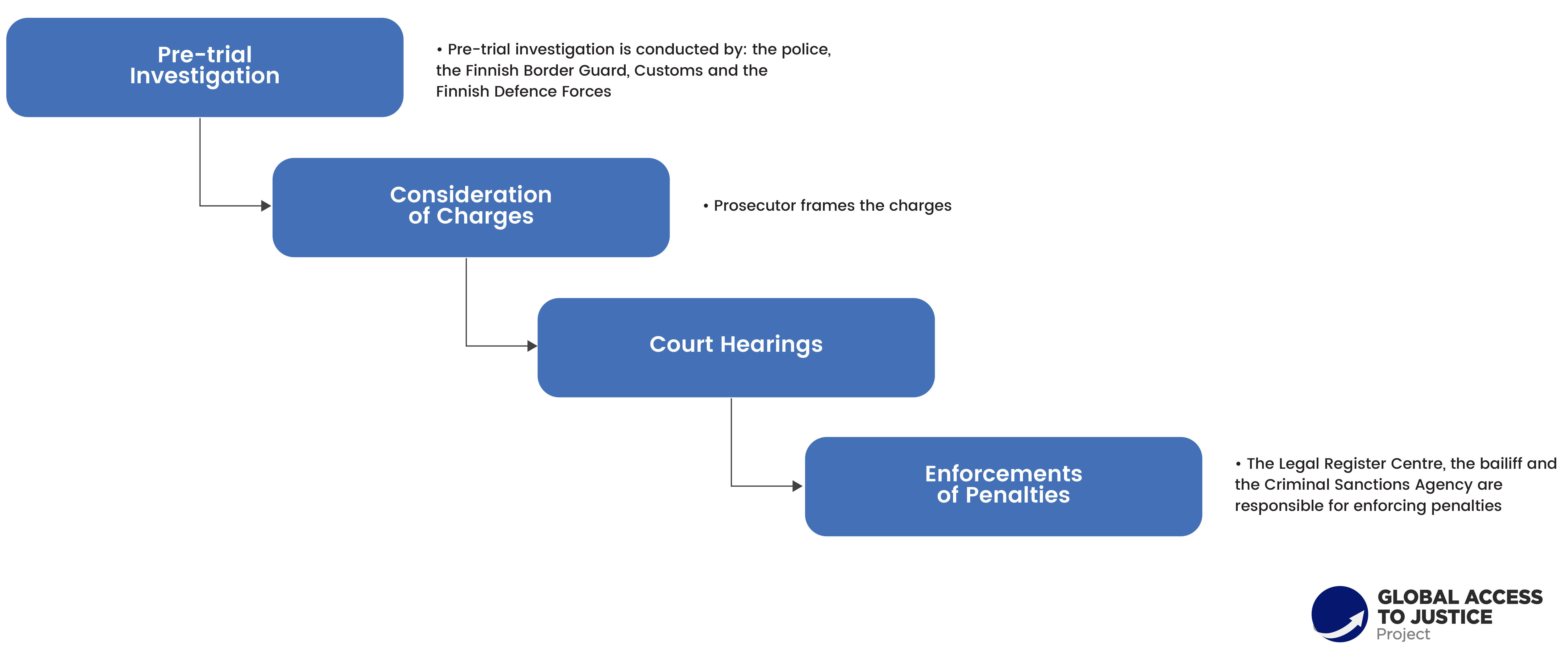

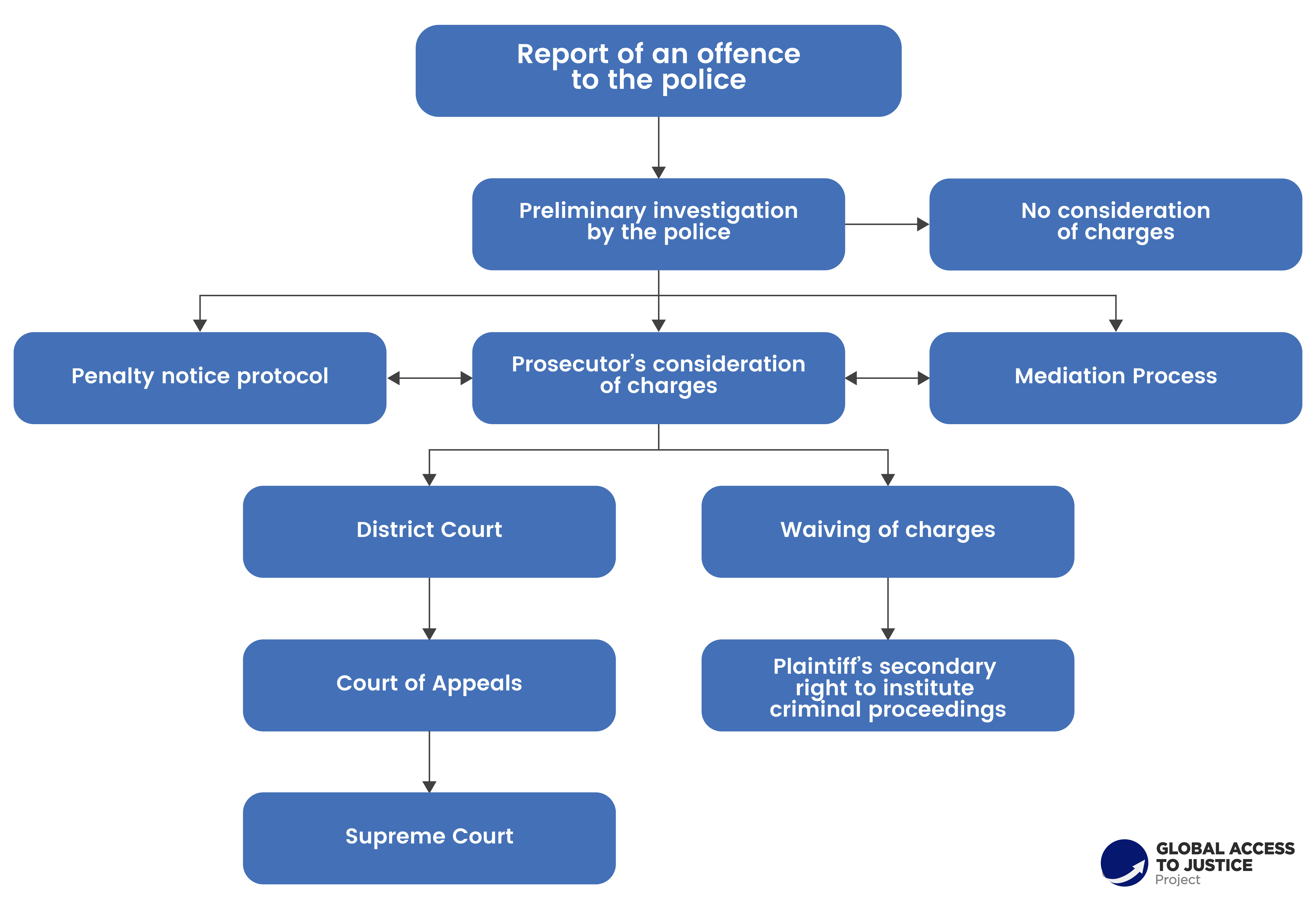

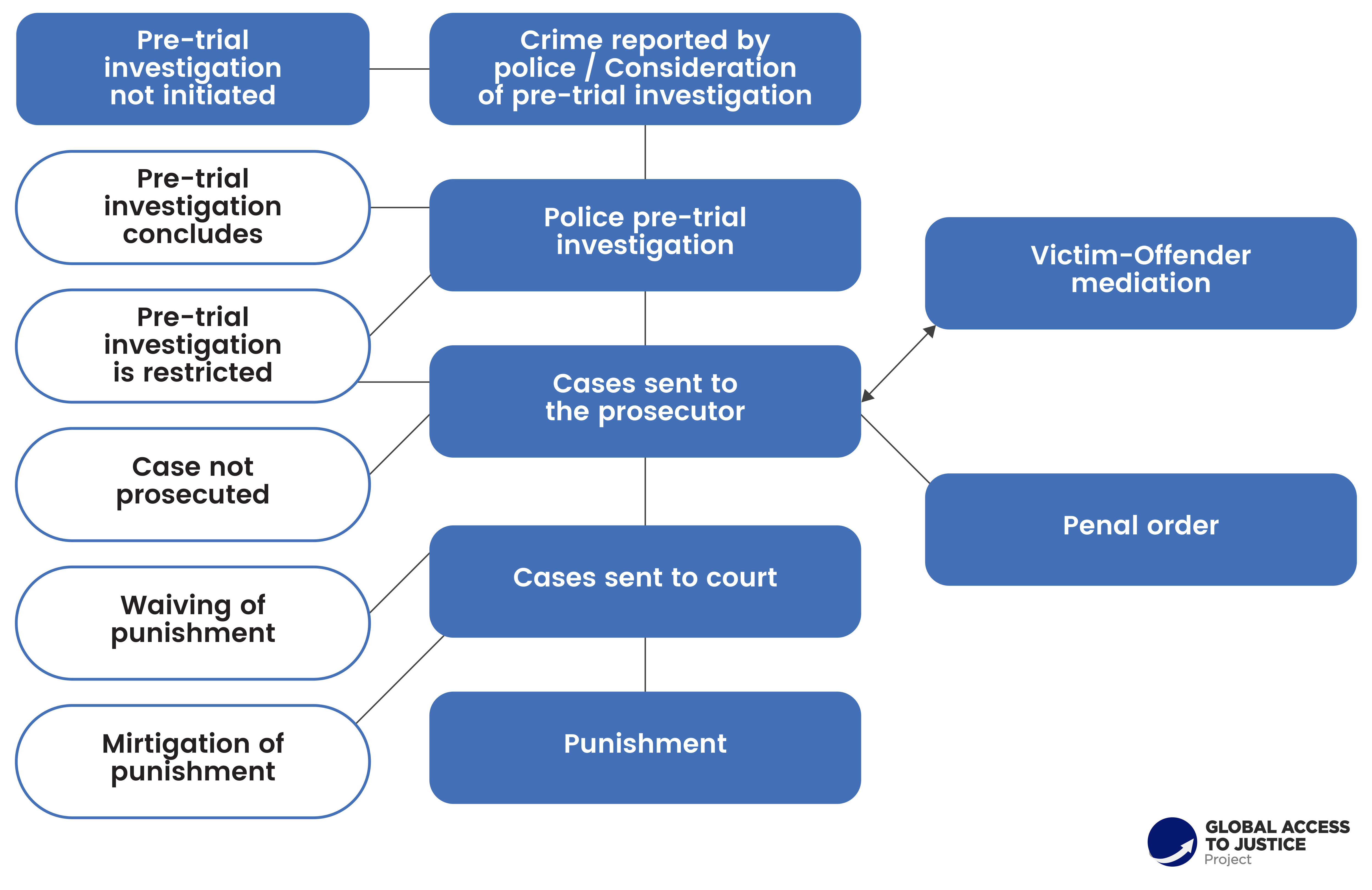

The criminal procedure has four stages: pre-trial investigation, consideration of charges, court hearing and enforcement of penalties.

Chart 05. Criminal Procedure Stages

A criminal investigation starts with a police report that may be made by the concerned party, or if the police suspects a crime has been committed, the police or authorities responsible for criminal investigation will conduct a criminal investigation. The criminal investigation is led by the police and the prosecutor. Upon completion of the criminal investigation, the criminal investigation report and supporting documents are submitted to the prosecutor. This is called the pre-trial investigation.

After the pre-trial investigation is completed and a prosecutor receives a record of the pre-trial investigation from the police, the prosecutor decides the further course of action that could result in either taking the matter to court, bringing charges or taking the decision to waive charges issued. In the case of petty crimes, charges may not be pressed. Nonetheless, in cases where the victim wants to bring charges, she or he can do so. This stage is called the consideration of charges.

Once the charges are brought to court, the defendant is notified of the charges brought against him, a summons is delivered and the defendant is provided with an opportunity to respond to it. In most cases, the summons also instructs the defendant to appear in court in person but it may also request that the defendant responds to the charges in writing before the trial commences.

The hearing starts with the framing of charges brought against the defendant by the prosecutor and the setting out of the victim’s claims in the matter. If the plaintiff so wishes, he can make a personal claim for compensation. It is then the defendant’s turn to be heard, and he can either admit or deny charges and must respond to any claim for compensation and present his views. Subsequent to the framing of charges and the response, evidence will be presented in writing and witnesses will be heard and examined.

After that, closing arguments of both parties will be heard and the court will make a ruling at the hearing. If the defendant, the prosecutor or the plaintiff is dissatisfied with the District Court’s decision, he or she can appeal to the Court of Appeal.

The appeal must be submitted within 30 days. However, a notice of intent to appeal must be filed first within seven days, with the District Court that made the decision.

Chart 06. Criminal Procedure Stages

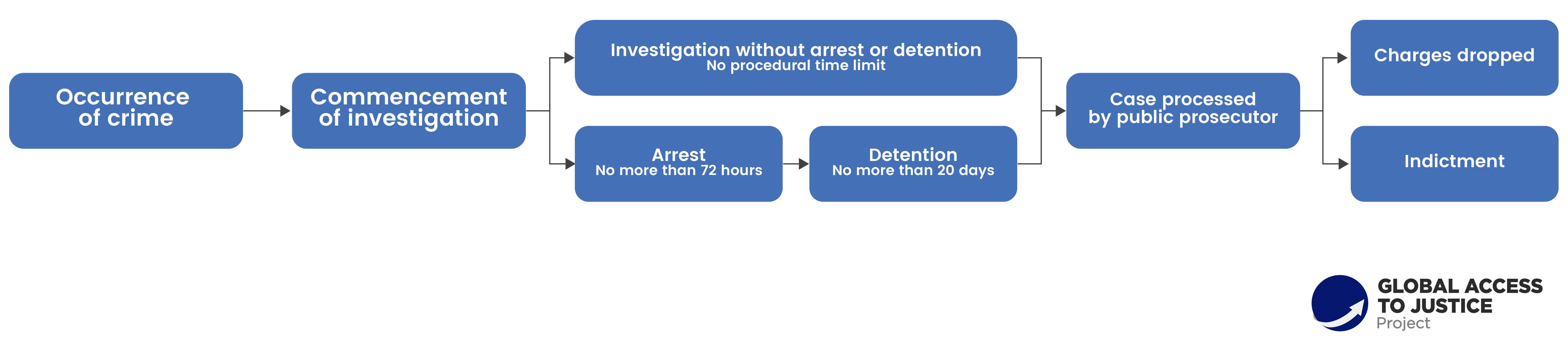

In cases where, during the preliminary investigation, a request for detention of the accused is made, a court of law has to make the decision on detainment during the pre-trial period. A request for detention is considered specifically in cases where it is suspected that the accused may flee, avoid the trial, hinder the criminal procedure and disrupt the investigation, damage evidence, and/or influence witnesses or the plaintiff, or continue with the criminal activity.

Equally a person can be detained if he or she is not a permanent resident of Finland or refuses to provide his or her name and refuses to state his name or address or gives false information concerning his identity, and if the identity is unknown and there is a reasonable suspicion that he/she may attempt to avoid the preliminary investigation or leave the country. In the above circumstances, a suspect can be detained without probable cause and if it is deemed important to detain the suspect for further investigation. Over and above the aforementioned conditions, the crime punishment must be no less than two years of imprisonment.

The criminal prosecution proceedings are provided in the chart below:

Chart 07. Criminal Prosecution Proceedings

3.2. Civil Procedure

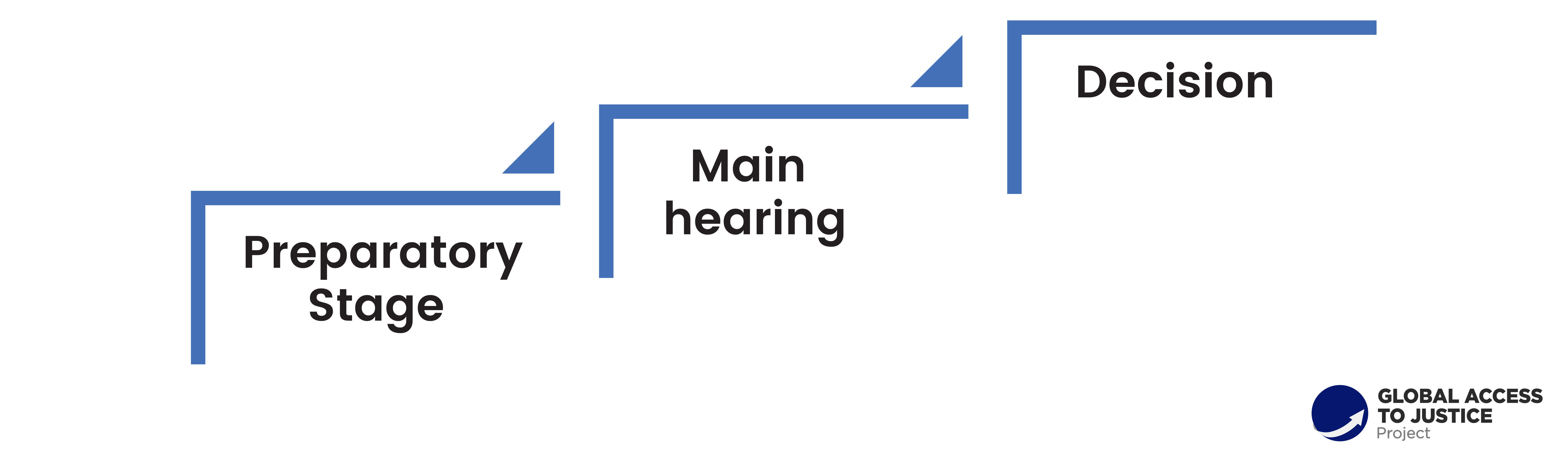

Chart 08. Civil Procedure Stages

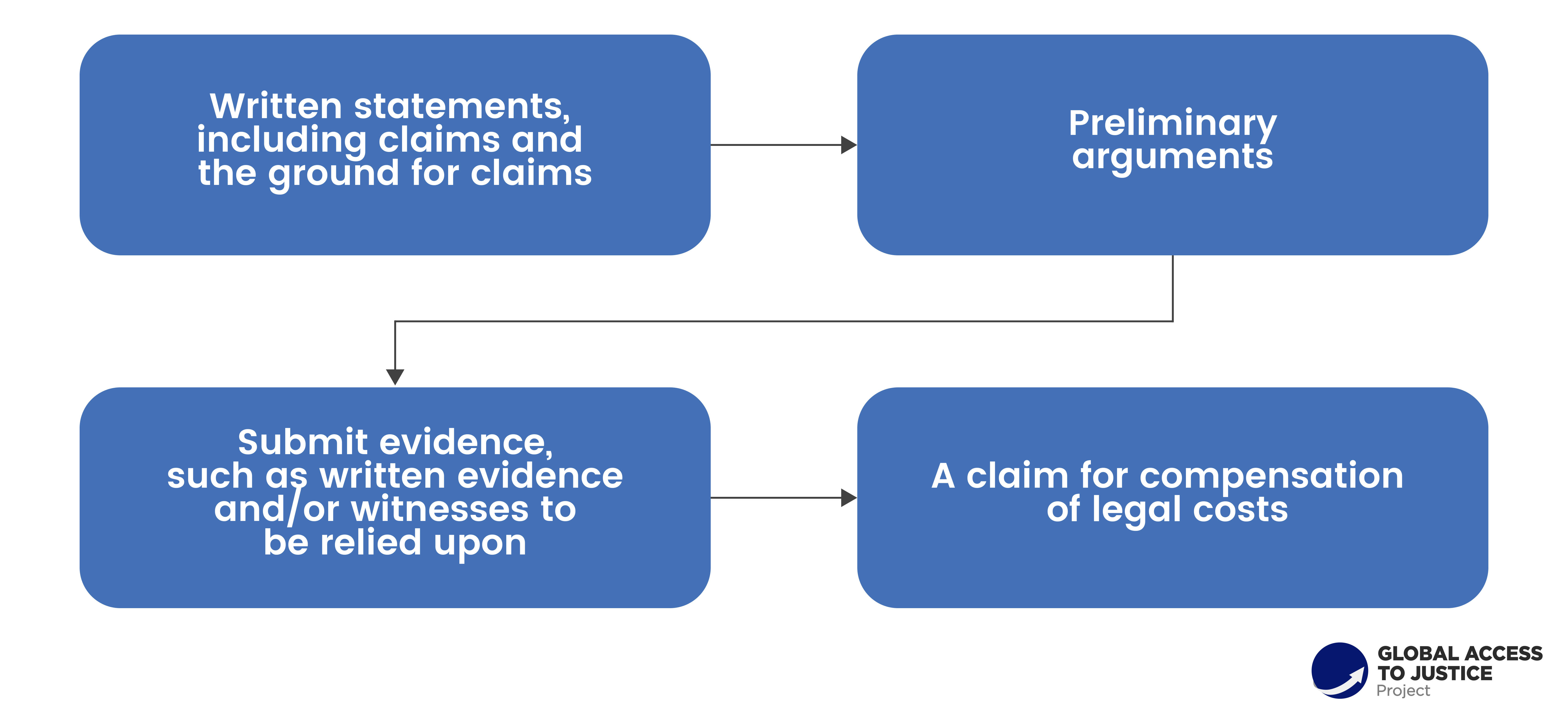

The Code of Judicial Procedure is the main statute that governs civil proceedings. The civil procedure can be divided into two distinct stages: the preparatory stage and the main hearing. In the preparatory stage, parties submit a number of documents along with filing of the case.

Chart 09. Preparatory stage

Subsequent to the preparatory stage, arguments are heard, written evidence is presented in court and witnesses are cross-examined. The hearing can take from one to several days. There can be an application for summary procedure if the matter is uncontested, but, if the defendant contests, the same proceedings are held as per the above procedure.

The limitation period for initiating proceedings in civil cases is three years. In certain cases, the limitation period may be interrupted by notice.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

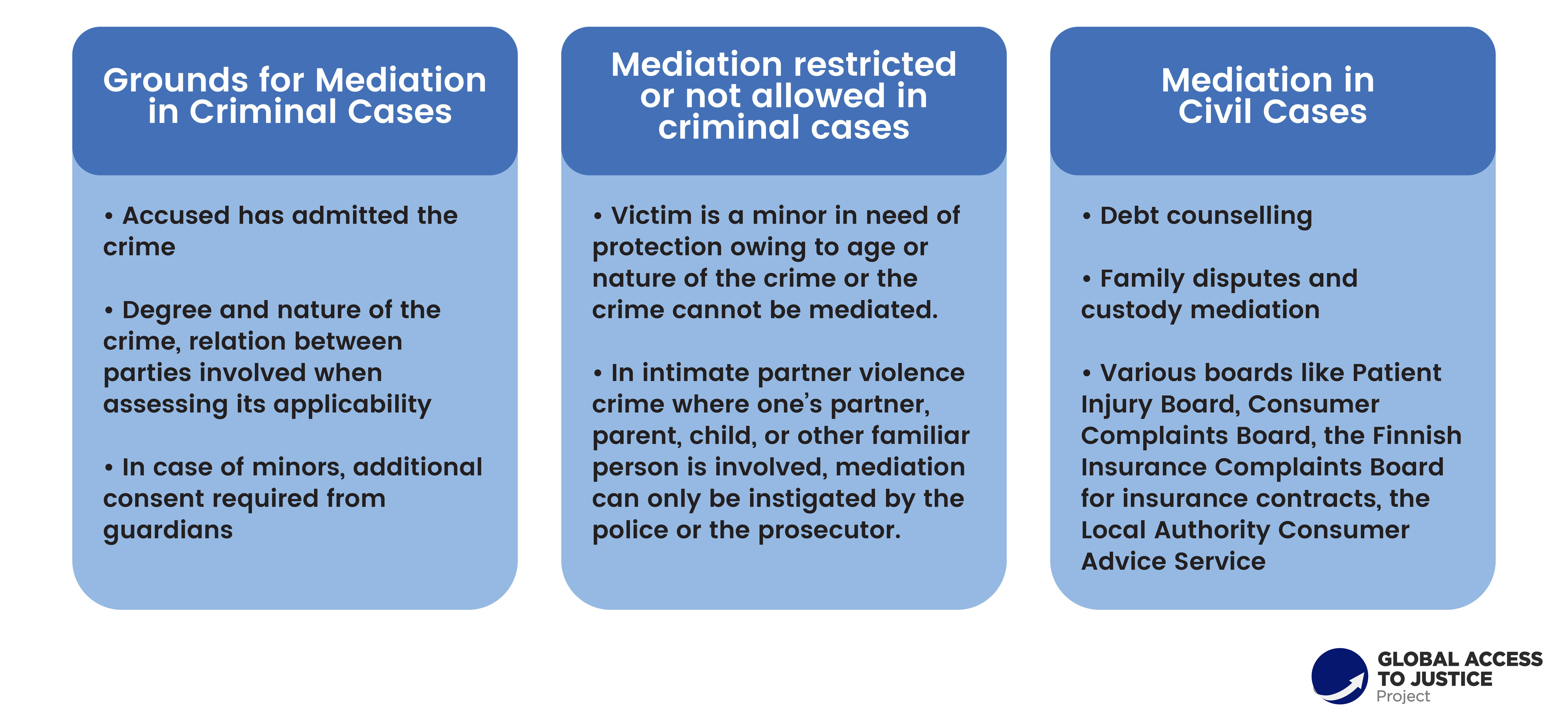

An out-of-court settlement is not compulsory in Finland, but it is possible in the majority of cases, such as business disputes, disputes between employers and employees, disputes between consumers and businesses, and disputes relating to landlords and tenants. Mediation is provided in civil and criminal matters in Finland. For sake of clarity, mediation in criminal cases will be referred to as Victim-offender Mediation (VOM).

Under Chapter 5 Section 26 of the Code of Procedure, it is stated that in civil cases, courts must establish whether the matter can be resolved amicably. In civil cases, mediation can be initiated when at least one of the parties involved is a natural person, and the disputed amount is minor.

Mediation should not be applied in cases of sexual offenses or cases of intimate partner violence with a prior history of violence or mediation. The police have also been instructed to prioritise complainants’ interests and apply careful consideration when assessing the suitability of more sensitive cases for mediation. In practice, mediation is more commonly suggested to younger age groups, and less directed to criminal cases where parties involved have a prominent criminal history. Currently, the most topical issue regarding victim offender mediation (VOM) regards the application of mediation to cases of intimate partner violence. The current discussion regards whether the regulations for this need to be further developed.

Victim-offender mediation (VOM) in Finland is available for parties involved in and affected by crime and is a commonly used method of alternative conflict resolution. Essential to the practice of VOM is the theory of restorative justice, which lays the groundwork for its implementation. Initiated during the 1980s, the scheme allows the victim to be heard, the offender to make amends and their social relations to the community be maintained. In criminal matters, VOM is provided in municipalities and in cases of mediation the victim meets the accused or person suspected of the crime through a mediator. A settlement agreement for compensation may also be agreed upon. Mediation is not compulsory but voluntary and it may be suggested by the parties, the police, the prosecutor, or the social welfare services.

Currently, the Finnish institute of health and welfare (Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos/ institutet för hälsa och välfärd) serves as the provider of VOM services, while the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (Sosiaali- ja terveysalan lupa- ja valvontavirasto / Tillstånds- och tillsynsverket för social- och hälsovården) supervises its implementation. The process and outcome of VOM operates through three laws; firstly, the legislation covering VOM as well as certain dispute cases which is the Act on Mediation in Criminal and Certain Civil Cases. The impact of VOM on the judicial outcomes of the criminal justice system rely on the Pre-Investigation Act and the Criminal Procedure Act.

Mediation in civil and criminal cases can be initiated by the parties themselves or be suggested by officials such as social workers, prosecutors and the police. Mediation can only be suggested to parties who personally and voluntarily consent to participation and understand its purpose. Additionally, the aims and means of mediation need to be deemed appropriate for the case and the party’s interests when assessing its suitability.

Chart 10. Mediation in Criminal and Civil Cases

VOM can be initiated only when parties involved personally consent to participate and understand the function of mediation.

According to the Act on Mediation in Criminal and Certain Civil Cases (section 3), VOM requires that the person accused of a crime confirms the general, factual occurrences of the event and that mediation is in the interest of the victim.

In a legal sense, the wording is weaker compared to “admitting” to a crime, since confessing to having committed a crime could he used as evidence in court, while confirming the general occurrence of events cannot be used as evidence of admitting the crime.

Despite the restrictions, VOM is an option available in criminal cases regardless of ongoing court proceedings. In other words, VOM can be attempted in instances where a criminal investigation has concluded or even in cases where a verdict has been delivered by court. If a mediated criminal case proceeds to court hearings, the parties involved cannot refer to information disclosed during the mediation without consent of all the parties involved.

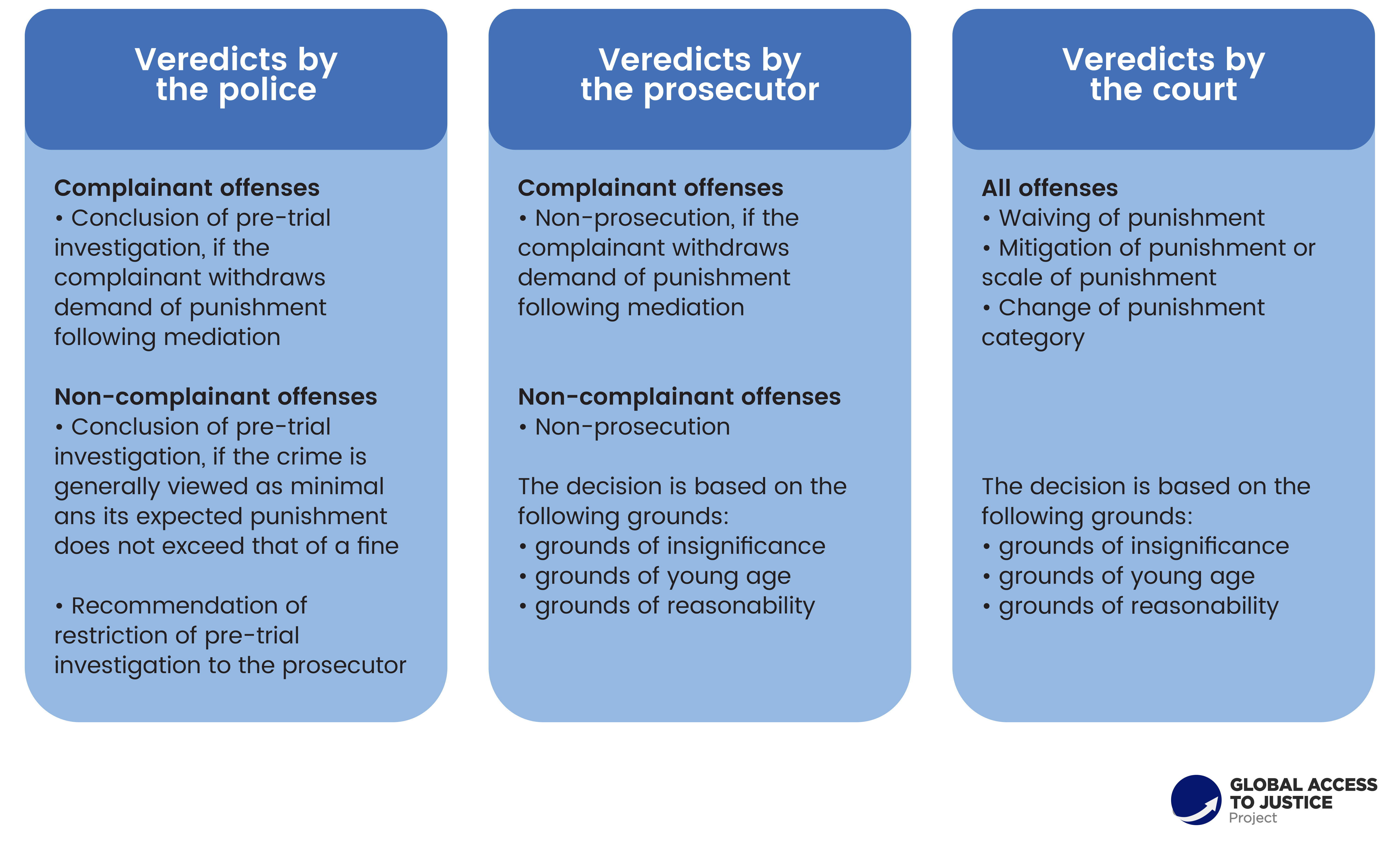

Thus, VOM can (if consent to disclosure has been given) influence the judicial verdict of the police, prosecutor and court. A successful mediation or a mediation attempt can serve as a ground for concluding the criminal case before it reaches court hearings. Regarding the influence of mediation, all authorities base their decisions on the aforementioned laws and official instructions.

3.3.1. Stages of VOM

Subsequent to filing of a criminal complaint and if there is a viable reason to suspect that a crime has occurred, the police must deliver a pre-trial investigation and inform the parties involved of any support service that may be of use to them. Offences where the prosecution rests on the injured party or complainant offenses, can only proceed to prosecution if the injured party demands punishment. Cases subject to public prosecution can be subject to investigation and prosecution even if the injured party does not demand punishment. A mediated criminal case can influence the verdict of the police in several ways, for instance, the pre-trial investigation is discontinued if the injured party revokes their demand for punishment following a successful mediation.

The impact of VOM on the criminal procedures and outcomes are presented in the chart below:

Chart 11. The crime process of victim-offender mediation

The oval boxes indicate the impacts of mediation on the criminal procedures and judicial outcomes.

Source: Aino Jauhiainen.

The prosecutor can only consider prosecution of complainant offenses if the injured party demands punishment. Regarding non-complainant offenses, the prosecutor has the right to raise charges regardless of the injured party’s demands for punishment. A successful mediation can serve as a ground for non-prosecution. A mediation agreement or attempt at mediation, as well as other actions taken by the suspect to amend the consequences of their crime can justify non-prosecution on grounds of reasonability.

If a criminal case sent to mediation proceeds to court, a mediated case can affect the outcome of the penalty. The court may decide to waive penal measures, on grounds of insignificance, young age and reasonability. Furthermore, a successful mediation serves as a ground for mitigation of the penalty.

The verdicts and grounds for non-prosecution are further outlined in the following model:

Chart 12. Impact of Mediation

Arbitration is an alternative dispute resolution method to litigation in state courts. Any dispute in a civil or commercial matter which can be settled by agreement between the parties may be referred for final decision to be made by one or more arbitrators.

The Arbitration Institute of Finland offers Arbitration, and also mediation regarding civil or commercial disputes, seemingly tending to move from mediation, and then arbitration if it does not work out.[1]

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

In civil cases that are undisputed, specifically cases concerning unpaid rents, consumer credit, and phone and electricity bills, a district court can apply a summary procedure. Mediation and processes relating to mediation especially in civil cases follow a simplified procedure and significantly reduce legal costs. This includes criminal cases where mediation is permitted, thus influencing the verdict and the nature of penalty imposed by the court.

[1] For more see, https://arbitration.fi/arbitration/

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

The Finnish Constitution guarantees the right to be heard by a competent authority without undue delay, the right to appeal, and the right to have a case dealt with appropriately. The right to a fair trial is enshrined in the Constitution.

Art. 21:

Protection under the law

Everyone has the right to have his or her case dealt with appropriately and without undue delay by a legally competent court of law or other authority, as well as to have a decision pertaining to his or her rights or obligations reviewed by a court of law or other independent organ for the administration of justice.

In Finland, the judiciary is independent from the legislative and executive branches. Judges are bound to act independently without any outside interference or interference from the executive branch. Further, the decisions of the Supreme Court and Supreme Administrative Court cannot be reviewed by any other authority. As set out in law, a judge cannot be dismissed except by a court order.

The Institute of Criminology & Legal Policy (ICLP) has conducted a study on perception of the law in Finland, titled “The legal situation in Finland.” The study revealed that confidence in the judicial system was lower among those who had dealt with courts than those who had no personal experience dealing with the judiciary or courts. Furthermore, court procedures were considered bureaucratic and general knowledge of legal expenses or of their rights in court was lacking among the participants.

In 2019 the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) criticised the handling of a case where an asylum seeker was denied asylum and sent back to Iraq and was killed after his return. The court held that Articles 2 (right to life) and 3 (prohibition of torture and inhuman treatment) of the European Convention on Human Rights had been violated. The court criticised the Finnish Immigration Services’ decision and assessment of the case. The asylum seeker was sent back to Iraq despite the case being still pending before the Supreme Administrative Court.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM[1]

In Finland, legal aid is governed by the Legal Aid Act and State Legal Aid Offices Act. It is the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice to administer legal aid, and the respective state legal aid offices make legal aid grant decisions. Legal aid is provided in civil and criminal matters.

At present there are about 220 public legal aid attorneys. Public Legal Aid Attorneys (PLAA) provide assistance throughout a case, from legal counseling to attending court. Legal aid services can be provided by both public and private lawyers. Private lawyers are employed in court cases where there is scarcity of lawyers, lack of capacity, inability to provide the service, when the legal service has to be provided in a particular language or if there is a conflict of interest. The Public Legal Aid (PLA) office needs to approve legal aid decision and grant permission to employ a private lawyer; subsequent to such approval, the state compensates the private lawyers for the legal aid provided.

Currently, Finland has PLA throughout the country that provide legal aid. The lawyers in the PLA function independently and can use their discretion as per the law. A handbook of interpretation of the legislation governing them is available for referral and guidance. Nonetheless, in case of denial of legal aid, a reconsideration or review of the decision can be submitted by the applicant to court. The process of reconsideration is different from the administrative appeal processes.

Legal aid covers legal counselling, drafting documents or terms of agreements, court attendance and out-of-court proceedings. Typically, legal aid is provided at the expense of the state. In Finland, legal aid in civil matters is provided partially or fully based on a person’s financial means and/or whether their legal expenses could be covered by insurance. On the other hand, in criminal proceedings and in matters of violent crime, a public defender is provided, and legal assistance is given irrespective of the financial status of the defender or victim. Currently, public and private legal aid providers are governed by the same law, and it is the responsibility of the state legal aid offices to make decisions related to granting legal aid. Much of the legal aid work is led by public legal aid attorneys working in Public Legal Aid offices (PLA).

In certain cases, legal aid may be given for cases abroad, like general legal advice. In certain cases, the Ministry of Justice may grant comprehensive legal aid in matters relating to child abduction, criminal cases where a person residing in Finland has become the victim of a sex offence abroad. As per the EU Member States, legal directive 2002/8/EC of 27 January 2003[2] the goal is to improve access to justice in cross-border disputes. The objective is to establish minimum common rules for the availability of legal aid in disputes between the Member States. As per the Directive, PLAs can submit legal aid applications to the competent authority of another Member State. Under the Directive, Helsinki Legal Aid Office accepts legal aid applications from abroad.

Over and above the legal directive, the European Agreement on the Transmission of Applications for Legal Aid is also applicable.

5.1. History of legal aid

The origins of the Finnish legal aid scheme go back to the 1950s. The 1950s saw the legal aid enactment that ensured citizens had state-funded legal representation in courts, carried out by private lawyers. In the 1970s, Finland witnessed further reform whereby the municipal legal aid law came into effect that established communal legal aid offices and provided free legal aid. The new legal reform ensured a mixed-model system where private and publicly employed lawyers provided legal aid services, thus ensuring that free legal aid was available via legal aid offices across the country. The 1980s reform further widened the scope of legal aid to cover out-of-court civil cases related to divorce and child custody issues and preliminary investigations in criminal cases.

In the 1990s, responsibility for Public Legal Aid Offices (PLA) was transferred from the municipalities to the Finnish state. It was then that client’s financial capacity to pay, i.e. means testing, was introduced. By 2002, another alteration in legal aid law meant that availability of legal aid was restricted to poor and middle-income clients. Yet, the reforms meant that the number of those eligible for legal aid increased, since the financial eligibility limits increased in 2009.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

The public legal aid system is funded by the Ministry of Justice. The respective laws governing legal aid in Finland are:

- Legal Aid Act

- Act on Public Legal Aid Offices

- Government Decree on Legal Aid

- Government Decree on Legal Aid Fee Criteria

- Ministry of Justice Decree on Public Legal Aid Offices

- Ministry of Justice Decree on the Locations of Public Legal Aid Offices and their Branch Offices

This includes all the subsequent amendments connected to the Acts and decrees.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

The Public Legal Aid Offices function administratively under the six legal aid and public guardianship districts. The districts are led by the Directors of Legal Aid. The PLAs are headed by leading Public Legal Aid Attorneys. The administrative units that function under each district are in charge of budget plans, recruitment, invoicing, and other administrative matters.

The services and the address of the PLAs are available online in Finnish, Swedish and English. The PLAs are in different municipalities. Legal aid for those without means is free, while others are charged or there is a co-pay element involved. At present, there is an initial legal aid charge of € 70 that is exempted if the person is not liable to pay based on means testing.

As far as calculating the deductible amount of legal aid is concerned, two elements are considered: the available means of the applicant and the supplementary deductible, which includes the assets of the applicant and his/ her spouse. The income of the spouse is not taken into consideration if the spouses are contesting parties.

Public legal aid covers attorneys’ fees and other costs of legal services in full or in part. This includes any other costs arising from court proceedings:

- Fee and remuneration of the attorney either in full or in part

- Attorney services up to eighty hours in all legal proceedings whether involving court or legal advice etc.

- Interpretation and translation costs

- Evidence costs

In addition, the state provides court documents and other official documents necessary for dealing with the matter free of charge; all notifications in the Official Gazette and an initial attempt at enforcement are also provided free of cost. However, state legal aid does not cover legal costs to be paid to the opposing party if the legal aid applicant loses the case.

5.4. Legal aid budget

In 2014, the overall legal aid budget for civil and criminal matters was €67.7 million. In Finland public lawyers are salaried public lawyers and therefore do not have budgetary duties.

5.5. Legal aid providers

It is mandated that a Public Legal Aid Attorney should have a post-graduate or a Master’s degree in law along with adequate experience in advocacy or adjudication. The majority of public legal aid attorneys hold the title of varatuomari. The title indicates those who have completed a judicial traineeship at a District Court and have a judicial qualification. They are appointed by the leading Public Legal Aid Attorneys, who in turn are appointed by the Minister of Justice.

The majority of Public Legal Aid Attorneys are members of the Bar Association, but all Public Legal Aid Attorneys, members or not, are governed by the Finnish Bar Association and mandated to follow the ethics laid down by the Association. Public Legal Aid Attorneys appear in courts and are expected to be competent in legal matters, this includes good oral and written skills, interpersonal skills, and negotiation skills.

The PLA Attorneys have considerable independence and discretion to accept or reject applications for legal aid in both civil and criminal matters. While the PLAs fall under the Ministry of Justice, the government does not take decisions with regard to overseeing the day-to-day administration. There is a small team of legal aid staff at the Ministry that oversees the functioning, but it plays no role in legal aid decision-making. The PLA is the first point of contact for a client, and each office makes its own decisions.

In addition, in Finland, the Chancellor of Justice also supervises the PLA, and deals with complaints relating to reasons for refusal of legal aid, or reconsideration of refusal of legal aid or any other error on the part of Legal Aid Offices.

An Advocate is a member of the Finnish Bar Association, who is subject to the supervision of both the Bar Association and the Chancellor of Justice of the Government. Advocates are under the obligation to observe proper advocacy conduct. The professional designation of Advocate is restricted only to persons entered on the Roll of Advocates of the Bar Association.

The Public Legal Aid Attorneys (PLAA) are governed by the Legal Aid Act and the State Legal Aid and Public Guardianship Districts Act.

5.6. Quality assurance

According to the Legal Aid Act (section 8), legal aid is provided by public legal aid attorneys. However, in matters to be heard by a court of law and in certain other types of cases, also a private attorney who has consented to the task may be appointed as an attorney. Only an advocate or a licensed attorney referred to in the Act on licensed attorneys may be appointed as a private attorney in a legally aided case.

As explained earlier, an “advocate” is a person who is registered in the Advocates’ Roll as a member of the Finnish Bar Association. As far as eligibility is concerned, a citizen of Finland or a national of the European Economic Area, who is at least 25 years of age, may be accepted as an advocate if they meet certain requirements of honesty and way of life suitable to being an advocate and if they meet the academic requirements stipulated for judicial office, and have the skills to practice as an advocate as per the by-laws of the Bar Association; and he or she is not a bankrupt and has full legal capacity (Advocates Act section 3).

The Disciplinary Board of the Finnish Bar Association oversees that the code of conduct is followed by attorneys-at-law, public legal aid attorneys and licensed legal counsels as stipulated under the Code of Conduct for Attorneys-at-law (applicable to attorneys-at-law and public legal aid attorneys) or the statutory ethical professional obligations corresponding to the Code of Conduct (applicable to licensed legal counsels). The Disciplinary Board can impose disciplinary sanctions for infringements.

The Legal Counsel Board considers the granting and revocation of the license of a licensed legal counsel and the imposition of a monetary penalty (Licensed Legal Counsel Act, section 3). The Legal Counsel Board is appointed for a five-year period. The members are: one justice of a court of appeal, one judge of an administrative court or a specialised court, one district court judge, one licensed legal counsel, and one person representing legal research and education. (Section 4 under the Licensed Legal Counsel Act).

The members of the Disciplinary Board of the Bar Association are judges, professors, public legal aid attorneys, licensed legal counsels and attorneys-at-law. The Board includes a Chairperson and 11 ordinary members, of which the Chairperson and six other members must be attorneys-at-law. Legal aid recipients do not take part in these boards.

As far as quality and assessment of legal aid is concerned, an annual quality assessment of legal aid services has been carried out since 2011. The data is collected using questionnaires from legal aid customers and self-assessments. The questions concern trust in legal assistance, client relations, efficiency, cost as well as professionalism, skills and knowledge of the assistant.

Sometimes additional monitoring is carried out e.g. by the National Audit Office of Finland (Valtiontalouden tarkastusvirasto Julkinen oikeusapu. Tuloksellisuustarkastuskertomus).

In 2018, the Government’s analysis, assessment and research activities team commissioned the Legal Policy Unit of the Institute of Criminology and Legal Policy (ICPL) to research the experiences of legal aid customers and the quality of legal aid services. The purpose of the study was to produce a comprehensive, multidimensional and realistic picture of the availability, quality and utility of legal aid in Finland. The primary aim of the study was to assess how legal aid can be further improved. The study comprised looking at public legal aid in general, and this included the experiences of asylum seekers and the customers of financial and debt counseling services who can avail of legal aid from 2019.

Research found that customer satisfaction differed among the classes of persons. For instance, in case of asylum seekers they had both positive and negative experiences. While the customer experiences in case of clients of both public legal aid and financial debt counseling were mostly positive. One of the key emerging gaps was that customers did not receive enough information on the progress of their cases at different stages of the legal aid process; the expertise of the counsellors and quality and fluctuations in their expertise and quality needed attention; and the waiting and queuing time to receive legal aid are sometimes too long in the busiest legal aid offices.

Interviews were conducted with asylum seekers, public legal aid providers, members of the Finnish Bar Association, offices of Financial and Debt Counseling and interviews with young customers seeking financial and debt counseling.[3]

Research found that customer satisfaction differed among the classes of persons. For instance, in case of asylum seekers they had both positive and negative experiences, whilst the customer experiences of both public legal aid and financial debt counseling were mostly positive. One of the key emerging gaps was that customers did not receive enough information on the progress of their cases at different stages of the legal aid process; the expertise of the counsellors and fluctuations in their expertise and quality needed attention; and the waiting and queuing time to receive legal aid were sometimes too long in the busiest legal aid offices.

Public Legal Aid Lawyers are provided training periodically, but it is not mandatory to participate in further training.[4]

5.7. Criminal legal aid

5.7.1. Scope of criminal legal aid

In the case of criminal matters, legal assistance is available through legal aid or via a public defence attorney. Thus, provisions of the Legal Aid Act apply to both civil, criminal cases and administrative cases. Additionally, in criminal matters the Criminal Procedure Act provides for the appointment of a public defender. A suspect can request for a public defender, and in some cases the court appoints one without any request.

In cases where a suspect is under arrest owing to an ongoing criminal investigation, the suspect has a right to public attorney. Public defenders are appointed by the court. However, in Finland a public legal aid attorney may act as a public defender and private practitioners can also be so appointed based on the defendant’s request. Unlike the legal aid scheme, the public defender scheme was put in place in 1998. Nonetheless, subsequent to the introduction of the public defender scheme, the public defender was considered the primary authority in criminal matters and in providing assistance to the accused. Across the schemes, lawyers charge the same fees.

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

As with legal aid in civil matters, in criminal cases also means testing applies. Although, under the public defender scheme an accused is guaranteed a public defender irrespective of economic or financial ability. In case the defendant is found guilty, he/she may have to pay the state for the public defence attorney’s fees as per the means testing applicable in the legal aid scheme. If, however, the defendant is acquitted, the state has to reimburse him or her for the costs of the defence, if paid privately by the defendant or covered by the legal aid scheme.

5.7.3. Process for obtaining criminal legal aid

The above sections on criminal cases and legal aid provide for the procedure in mediation and court cases where legal aid is available.

As per the principles of fair trial legal representation and the right to be heard, an accused has to be provided the right to be heard and an opportunity for a fair trial under the principles of natural justice.

In Finland, in criminal matters both proceedings and pre-trial investigations the defendant is entitled to a public defender irrespective of the financial situation. If however the defendant is convicted, he or she is obligated to reimburse the State for the lawyer’s fee based on the financial situation.

A public defender is appointed on request of the suspect or on request of a person arrested or detained. The court can also appoint a public defender for a person under 18 years of age or any other person incapable of taking the decision.

A public legal aid lawyer or a private lawyer can be appointed as a public defender.

5.8. Civil legal aid

5.8.1. Scope of civil legal aid

In Finland, the scope of legal aid is defined by the ‘need’ for expert assistance in a matter. This provides for a wide coverage. There is no restriction on types of cases, but certain matters such as petty criminal cases or uncontested divorces are not covered. Civil cases explicitly exclude cases regarding membership of a municipality or other public body, tax matters, and cases involving the registration of documents and records. However, if it is considered that the reason for providing legal aid is weighty, legal aid will be provided. The exclusions are not absolute. In addition, legal aid is not available as per the Aliens Act during an initial asylum interview. Legal aid is limited to individuals. The exclusion relates only to representation in court, thus legal advice and legal counselling is available in all cases. There are other notable exceptions relating to asylum cases, where representation may not be provided in case of initial asylum interview or debt settlement cases. Nonetheless, legal advice may be provided in all cases.

As far as determining whether the person is eligible for legal aid, this is done by lawyers at the Legal Aid Offices. If the applicant is in need and meets the financial eligibility requirement, assistance is provided, with the exception of minor or frivolous cases. The matter is decided independently by the Legal Aid Offices without any interference from the Ministry of Justice.

Finnish legal aid covers the applicant for cases in all courts including appeals. Legal aid is limited to 80 hours of lawyers’ time. A court may grant an extension and legal aid may be continued if there are special reasons for continuing legal aid, on grounds of access to justice and based on the subject matter.

Likewise, in cases of appeal 80 hours is not enough time, and an extension application has to be made. The extension is granted based on the subject matter and on the person’s need for access to justice. As long as the case remains open or is not concluded, legal aid continues. Legal aid however does not cover enforcement of a verdict but the applicant, if covered by legal aid, is not required to pay the enforcement fees to the enforcement agency.

In Finland, according to the legislation, legal aid can also be granted retrospectively, as long as the application is made at the earliest possible time and before the case is concluded.

5.8.2. Eligibility criteria for civil legal aid

Applicants can apply for legal aid by submitting a legal aid application to the PLAO or via an electronic legal aid application form. Once a date is allocated for a meeting, applicants have to submit all the necessary financial documents, such as proof of income, capital, and debt. Income and capital are taken into consideration in determining the eligibility of the applicant for legal aid. In the case of private lawyers, an application form is submitted by the lawyer along with all the documents.

As per the Legal Aid Act:

“The economic situation of the applicant is estimated based on the funds available to him or her per month (available means) and his or her assets. The available means are calculated based on the monthly income, necessary expenses and maintenance liability of the applicant and his or her spouse, domestic partner or registered partner. If the applicant is a suspect or a defendant in a criminal case or if the spouses are opposing parties in a case or are separated by reason of irreconcilable differences, legal aid is determined based on the means of the applicant alone.”

For the purpose of the means testing, applicant’s monthly net income calculated after deducting taxes, monthly expenses, and assets and wealth are taken into account for calculation. It is after the said calculation it is determined if legal.

For instance, as per the current calculations if the monthly funds of an individual applicant are € 600 or less, legal aid will be granted without any client contribution, and legal aid with a contribution will be awarded if the income is between € 600 and € 1300. Calculation and deductions also take into account spousal income. Finland charges a basic contribution of € 70 from everyone above the lower contribution limit. Over and above that, there is a progressive contribution from 20–75% based on the applicant’s income. There is no upper limit on the amount of percentage contributions. In Finland, in civil litigation the losing party has to incur the litigation costs of the winning party. The litigation costs are not covered by the state legal aid scheme. Research shows that this not only deters poor and middle-income people from litigation, even when their case has merit, but also has consequences for access to justice.

As per the data in 2014, private lawyers took 32,000 legal aid cases. Of that number, around 66% were criminal matters, 14% fell under the Aliens Act dealing with asylum seekers, and 11% were family matters. The number of cases under the Aliens Act has increased subsequent to the 2013 legislation that provides legal aid to asylum seekers.

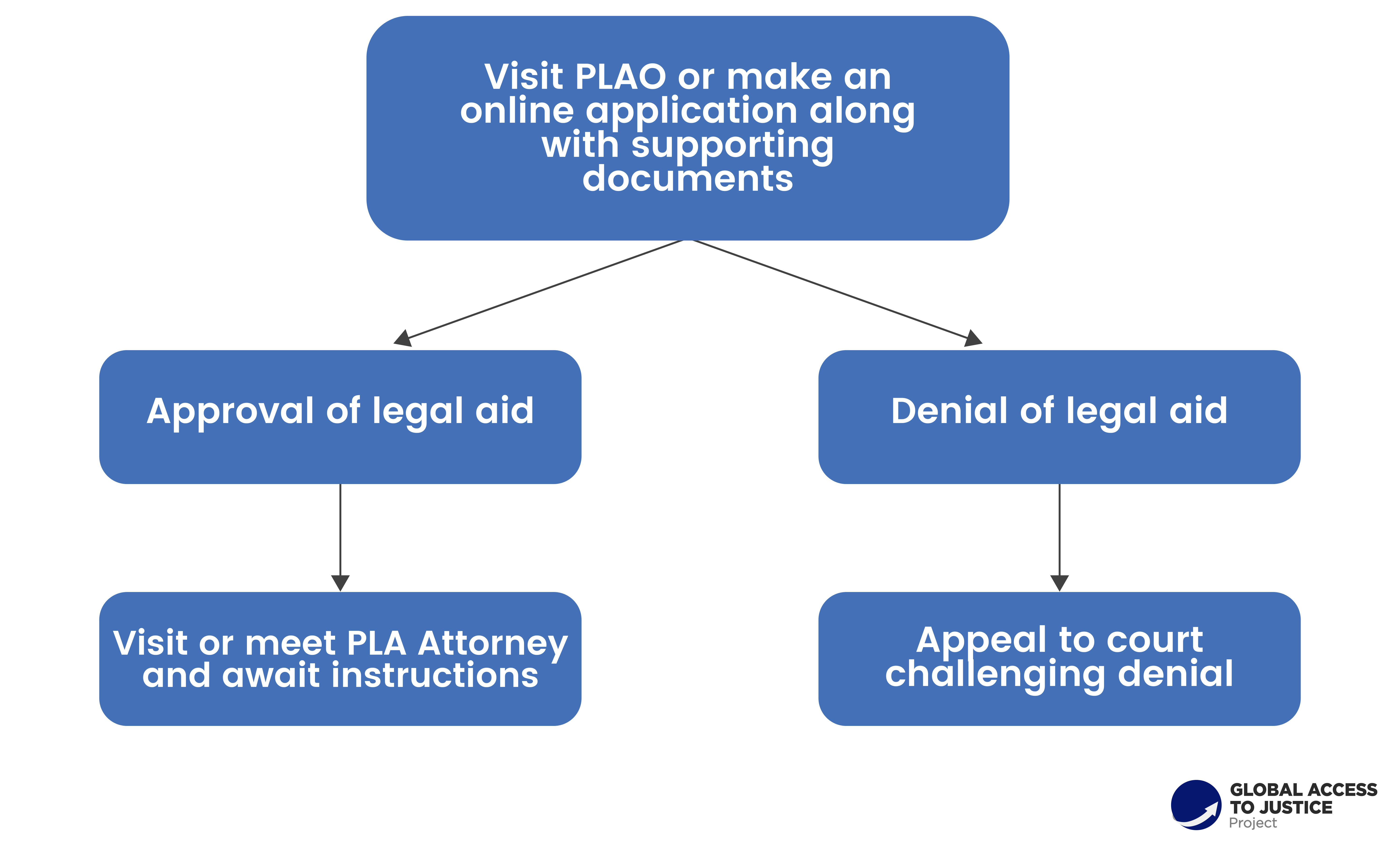

5.8.3. Process for obtaining civil legal aid

An applicant can apply for legal aid directly to any of the PLAO irrespective of where he or she resides. A legal aid application form must be completed and supporting documents relating to income also have to be submitted. The details of the case for which legal aid is being sought and, if the applicant has any insurance that covers legal aid, the insurance document should also be submitted. The applicant can visit the nearest office directly or can submit an online application. Subsequent to the submission of the application, PLA Attorneys independently assess each application and may require further clarification or documents to assess whether legal aid can be granted, based on the subject and means-testing.

Chart 13. Legal-aid Application process

Once legal aid is approved, a lawyer is appointed to attend to the client. If the PLA Attorneys do not have capacity to take on the case, a private lawyer may be suggested. As far as the application is concerned, a private lawyer may also make an application for legal aid to the PLAO when the case needs legal representation in court. Private lawyers cannot provide legal aid at the advice level.

In the event of denial of legal aid or if an applicant does not meet the requirements of free legal aid, the applicant may challenge the decision by submitting a review to the court. The decision can be challenged whether the denial is due to subject-matter or based on means testing.

Both the granting of legal aid and termination or amendment of legal aid is an independent decision made by the PLA Office. In case legal aid is terminated, the person given free legal aid may be expected to reimburse for the legal costs incurred so far in the case until termination. The termination of legal aid can be reconsidered by the Administrative Court. If the court rules in favour of the applicant there is no possibility for the PLA to appeal the decision and legal aid should be provided. The termination or amendment of legal aid is made if there is a change in circumstances or if the legal aid should not have been granted in the first place.[5]

In cases where legal expenses are covered by an insurance claim, legal aid is not provided or granted. Also, matters that do not require expert or attorney advice are not covered.

5.9. Holistic legal services

In Finland, with respect to family mediation services and child custody, municipal social welfare boards are responsible. Legal aid is not provided in these cases. Family counselling and social welfare services are responsible for child custody-related conflicts. Social welfare services are assigned to the task. Mediation services work in close collaboration with social welfare services. The services offered by social welfare services is state appointed and non-legal.

5.10. Legal aid before regional human rights mechanisms

Finnish public legal aid does not provide legal aid for cases filed in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) or the UN commissions. In case of an application to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), an applicant may be granted legal aid by that Court.

5.11. Alternative sources of legal assistance

As mentioned earlier, legal advice and fees are covered by insurance and trade unions in certain cases. Finland does not have a tradition of legal clinics in universities.

5.12. Peculiarities of legal aid in Finland

Problems and peculiarities relating to legal aid availability in Finland are specified in detail above and in the conclusions. Kindly refer to the same.

6. COSTS OF RESOLVING DISPUTES WITHIN THE FORMAL JUDICIAL MACHINERY

6.1. Overview of judicial costs for litigants

In Finland, litigants in general are required to pay a court tax or fee to start proceedings at a court of general jurisdiction. For instance, the district court fee is € 260 in criminal matters, appeals under the enforcement code, restraining orders, and matters in which settlements are not allowed. A fee is also applicable in the Courts of Appeal.

In case of a criminal matter where a public prosecutor is appointed or if a restraining order is imposed by a District Court, no fee is payable. In civil matters and land court matters, the district court fee is € 510. The fee for a Petitionary matter is € 260. In criminal matters, the fee is not payable in the event the Court of Appeal rules in favour of the appellant. For other matters in the Courts of Appeal, the fee is € 510. In the Supreme Court, the court fee is € 510. In criminal matters, no fee is payable if a decision of a lower court is amended in favor of the appellant.

In the Administrative Court, the court fee is € 260. The fee is not payable in case the Administrative Court amends the subject to appeal in favour of the appellant. That is, the applicant is reimbursed if the applicant lost the case at first instance but won the appeal. In the Supreme Administrative Court, the court fee is € 510, and as in the lower courts, no fee is payable if the decision subject of appeal is amended in favour of the appellant.

Over and above the court fees, there are additionally a copy charge, extract charge and certificate charge for requested documents. Other separately compensated costs are publication costs in the Official Gazette and other publications, unless publication costs are included in the basic charge, which is the case in some petitionary matters. Additionally, a tape or record fee as well as delivery charge is collected for audio or video recordings or other records. Full charges will also be collected for specific services abroad.

As far as calculation of court costs are concerned, the court fees for instance includes trial charges and petition charges. They also include the costs of delivery of the official instrument containing the decision on the case in question and other incidental charges relating to processing of the case. A court fee is also charged when a claim, petition, or appeal is withdrawn.

The responsible party for the costs is the initiator of the matter (plaintiff or petitioner), and in cases of appeal, the appellant. The charges collected by the courts are governed by The Act on Court Fees (“Tuomiostuinmaksulaki”, 1455/2015) and the corresponding Decrees.

6.2. Exemption from judicial costs

In Finland, there is no specialised procedure for exemption from legal costs as such, but economically vulnerable people may receive free legal representation as part of legal aid (see section 5 above), which covers all sorts of matters. A beneficiary of legal aid is also exempted from payment liability of court fees listed above in section 6.1.

The procedure for applying for exemption from judicial costs is stated above. Yet, in the event litigants lose the case, they are liable to pay the litigation costs and expenses of the other side. The state does not compensate the opposing party for any legal costs in the event that a recipient of legal aid loses the case.

Under the Code of Judicial Procedure (“Oikeudenkäymiskaari”, 4/1734), the court has power on its own motion to reduce the payment liability of the party or excuse them altogether. If, in the view of the court, it would be manifestly unreasonable to render one party liable for the legal costs of the other party, taking into account the situation of the parties, or the significance of the issue at hand, and all aspects of the case, the court may reduce the payment liability.

In Finland, the Institute of Criminology and Legal Policy / Kriminologian ja oikeuspolitiikan instituutti” (ICLP) has conducted research on the judicial costs in the civil matters over the past twenty years. The research has shown that the judicial costs have risen steadily from the mid-1990’s to date, but the effect of risen costs on access to justice/courts has not been researched as such.[1]

6.3. Mechanisms to reduce costs by variations to courts and procedures

In Finland, there are neither simplified procedures within the regular courts nor courts of special jurisdiction that specifically aim at reducing costs for litigants. However, in the Insurance Court (“Vakuutusoikeus”), a special court that deals with income security matters, proceedings are free of charge for private individuals. The Insurance Court has jurisdiction in matters concerning for example pension matters, unemployment benefit, housing allowance, financial aid for students and disability benefits paid by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The applicant however is responsible for possible costs of representation by an attorney, but may be granted legal aid to cover the costs.

Despite the absence of simple procedures with the aim to reduce costs, undisputed civil cases that go to district courts and are resolved in a summary procedure have a lower court fee, approximately ranging from € 65 to € 86 compared to the standard fee of € 510.

In addition to the formal dispute mechanisms, there are various Ombudsman Offices where a complaint can be filed.

- Ombudsman for Equality (Tasa-arvovaltuutettu)

The Ombudsman for Equality is an independent authority whose main duty is to supervise compliance with the Act on Equality between Women and Men. The Ombudsman’s role is to combat discrimination and promote equality.

- National Non-Discrimination and Equality Tribunal of Finland (Yhdenvertaisuuslautakunta)

The task of the National Non-Discrimination and Equality Tribunal of Finland is to give legal protection to people who consider they have been discriminated against or victimised. There is no fee for petitions and no service fees. The mandate of the Tribunal does not cover matters related to family life, private life or practice of religion. The Tribunal may prohibit discrimination by imposing a conditional fine.

- The Consumer Disputes Board (Kuluttajariitalautakunta)

The Consumer Disputes Board is an impartial and independent expert body whose central values are justice and easy access to justice. The Board makes recommendations that cannot be enforced coercively, however businesses comply with the Board’s decisions in over 80% of cases. Cases are handled free of charge and activities are funded through the state budget. The processing times at the Consumer Disputes Board are around as long as at the regular courts, which could be critiqued as the Board is supposed to be a simpler mechanism to solve consumer disputes. In 2018, the average processing time for a claim at the Board was 11 months (median 8 to 7 months), and for civil matters in district courts 9 to 8 months.

7. THE PROTECTION OF DIFFUSE AND COLLECTIVE RIGHTS

Finland has both collective and diffuse rights.

As far as collective rights are concerned, Finland has collective agreements that are between trade unions and employers’ federation whereby terms and conditions of a group of employees or a sector are decided. The collective agreement sets out the basic rights, working conditions, employment standards, and pay (the minimum rates of pay and various bonuses).

Most collective agreements in Finland are generally binding for the sector or industry in question. This means that an employer is obligated as per law to respect the minimum employment standards that are guaranteed under the collective agreement, even when the employer does not belong to the organisation that concluded the agreement and the employee is not a union member. Finland has around 160 universally binding collective agreements. Over and above that, the central labour market organisations may decide on day-to-day work matters and their compliance with collective agreements.

As far as collective rights are concerned, the indigenous Sámi population is a legally recognised indigenous population in the EU and in Finland. The Sámi live mainly (but not only) in an area covering the northern regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Russian Kola peninsula. According to the Sámi Parliament, Sámediggi, there were 10,463 Sámi living in Finland in 2015. The Sámi homeland includes the municipalities of Enontekiö, Inari and Utsjoki and areas in Sodankylä. The area amounts to 35,000 km².

In Finland, the Sámi have a special status under the Finnish Constitution, and they have the constitutional right to self-govern in the areas of language, culture and traditions in the Sámi homeland. The UN Declaration on Rights of Indigenous People and the ILO convention no. 169 stress the importance of institutions that represent indigenous peoples and whose participation and rights must be guaranteed. For tasks relating to cultural autonomy, the Sámi can elect from among themselves a Sámi Parliament.

The Finnish Mining Act takes into consideration the full realisation of the social, economic and cultural rights of the Sámi people, as established in Article 2 of ILO Convention. The Act also seeks to control and restrict the impact of mining activities in the Sámi territories, and ensure that Sámi rights are not exploited or compromised. The Act provides for a right of appeal. The Act extends protection to the Skolt Sámi.

For instance, in Ilmari Länsman et al. v. Finland, the petitioners filed a case before the UN Human Rights Committee claiming that Finland had violated Article 27 of the ICCPR.[1] In the petition they claimed that the decision by the Central Forestry Board to sign a contract with a private company permitting quarrying in a Sámi area, near mount Etelä-Riutusvaara, which is a sacred place for the Sámi, was violative of Art. 27 of the ICCPR. The Committee concluded that in this case there was no violation of Art. 27 of the ICCPR.

In Jouni E. Länsman et al. v. Finland, the petitioners claimed that the approval granted by the Finnish Central Forestry Board to construct roads in an area suitable for winter herding was in violation of Article 27 of the ICCPR and the United Nations Draft Declaration on Indigenous Peoples. The Committee ruled that there was no breach of Art. 27 of the ICCPR.

More recently, in a case decided by the Supreme Administrative Court, the Sámi Parliament under Section 165 of the Finnish Mining Act, 2011, challenged the permit granted to the Finnish Safety and Chemicals Agency (TUKES) to start mining activities in the Valley of the Kings, in Inari, a Sámi territory. The court ruled in favour of the Sámi Parliament. Subsequently, TUKES appealed to the Supreme Administrative Court of Finland, but the case was dismissed in favour of the Sámi Parliament.[2]

Despite the rights guaranteed in the Finnish Constitution, there are challenges in realising the rights of Sámi.[3] This has been researched extensively in Finland.[4] More recently, there have been discussions on disputes between the Sámi and the Finnish government‘s plans to build railways across reindeer rearing areas.[5]

As far as diffuse rights are concerned, the Everyman’s Right (Jokamiehen Oikeudet) is a diffuse right that gives every person in Finland the right to explore, forage, fish with a line rod, and enjoy nature across the country. The Everyman’s Rights protects a person’s right to enjoy nature without transgressing private property and violating environmental protection laws.

In Finland, a class action suit can be filed in disputes concerning a defect in consumer goods or if there has been a contradictory interpretation of a contract. Likewise, in case of a dispute between a consumer and a business owing to a product, sale and marketing of investment products and insurances, a class action suit can be filed.

A case is heard as a class action, if several persons have similar claims against the same defendant. Currently, the Consumer Ombudsman, would bring a class action against the defender. In case of class action cases, applicants are not liable for legal costs. It is the Consumer Ombudsman, or by the defendant that would pay the legal costs.

8. PROFESSIONAL LEGAL ETHICS

In Finland, only members of the Finnish Bar Association can use the title of asianajaja or advokat. To become members of the Bar Association, one must have a Masters’ degree in law. As per the Advocate’s Act 1958, which regulates the Finnish Bar Association, the asianajaja is obligated to observe professional ethics and fulfil his/her duties. In addition, there is a Finnish Code of Conduct, 1972, that lays down professional ethics. Over and above that, there are special ethical codes for remuneration, marketing, administration of client money, indemnity insurance that advocates have to comply with. The professional ethics and the various rules are in line with the European Code of Conduct for Lawyers. An advocate in Finland has to undergo a practical training of four years, and must be supervised by a law firm or its equivalent for at least two years. There is a legal professional ethics examination organised by the Bar that must be passed.

Advocates are required to be independent and they should not be under any external influence or any political influence that may impact their professional duties. As far as marketing or advertisements of services is concerned, the information should be truthful and as per the professional ethics. Confidentiality should be observed with respect to the case and all information relating to the client that may have been shared in confidence.

An advocate has a professional responsibility. The Bar Association Board has to ensure that advocates fulfil their duties as per the laid down professional ethics. In the event advocates fail to comply with professional ethics, the Bar Association can take disciplinary action after a written complaint has been filed against the said advocate. An appeal against the Bar Association verdict can be filed in the Appellate Court of Helsinki. In case a lawyer is dismissed from the profession, he or she may still continue to practice, but not under the asianajaja title.

As far as teaching professional legal ethics is concerned, ethics are not part of law professional studies in law school programs. The teaching on ethics is erratic since it does not form part of the official or mandatory curriculum. Further, law school programmes do not require law students to take a pledge upon graduation or explicitly commit to upholding legal and social values at any point. In Finland, there is no lawyer’s admission ceremony that all graduates are mandated to attend and the graduation ceremony does not include an oath ceremony.

Nonetheless, prior to entering the voluntary year-long court training that familiarises trainees with judicial tasks and is carried out in district courts, the trainees must give a judge’s affirmation[1]. The trainees are often those with a master’s degree in law. In addition, to become a member of the Finnish Bar Association, lawyers must pass the bar examination, which includes an ethics part. The ethics part includes a two-day training course on ethical issues. Attorneys-at-law and licensed legal counsels are obligated to follow the ethical norms of the Bar Association.

Lawyers in Finland may engage in the legislative process and they may as lobbyists represent companies, organisations and NGOs. Law professors often participate in public discussion and provide legislative reform suggestions e.g. by giving interviews and using social media. They may also be consulted in the law drafting process as experts.[2]

9. TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE

According to data from Statistics Finland, 80 per cent of Finns aged 16 to 89 use the internet. The use of the internet is calculated on a daily basis, and as per the data 68 per cent use it several times a day. For instance, this includes the use of the internet using tablets outside the home and workplace. In 2015, before the Parliamentary elections, it was observed that 45 per cent of Finns used a voting aid application. Similarly, the use of smartphones among Finns stands at 69 per cent. The shift to smartphones has also led to multiple internet connections within the same household. This includes use of online banking (80%) and the use of voting aid applications among persons aged 25 to 34 to search for a suitable candidate.

The use of services for booking appointments at the local health station, checking for vaccinations and checking health records (Omakanta) are available on the internet and via a telephone service. More recently, videos are used by nurses to check on elderly patients living in remote parts of the country.[1] Also, there is an increased focus on digitalisation and the use of care-robots to meet the growing demands of care and the scarcity of nurses.[2] Social and healthcare personal data is recorded and saved in Kanta services. The data is available for personal use, but also shared with professionals in Finland and within Europe if individual consent is given. The personal data may also be used for monitoring and research and compiling statistical information for secondary purposes after anonymisation. The data typically consists of all medical treatment received, vaccinations, prescriptions, and other data related to personal well-bring.

Over and above that, as far as legal aid is concerned, the application procedure, processing times and all details regarding the application for legal aid are available online. Online and telephone advice are available in three languages: Finnish, Swedish and English. The purpose is to ensure that access to legal aid is available in far flung places in Finland, especially Eastern Finland where applicants may find it difficult to reach Legal Aid Offices physically.

As part of the Government’s attempt to increase efficiency and use of electronic services, it is mandatory to use electronic services for submitting an application for a summons in an undisputed civil case, especially in cases where summary procedure is applicable. The application for a summons must be submitted to a district court through either the e-service or the data transmission interface (Santra) of the judicial administration. The e-service can be used by companies and corporations, debt collection agencies and municipalities.

10. UNMET LEGAL NEEDS

Finland, from a comparative international perspective, has a high standard of universal education, and relatively well functioning public service with universally available social and health care. As per a 2013 survey conducted by the EU commission, 85 percent of Finns perceive the legal system as trustworthy.[1] Furthermore, Finland is built on the Nordic Welfare State model idea of universal state provisions ensuring a certain basic level of service for all its citizens irrespective of income or social status. Citizens should have equal possibilities to understand and enforce their rights also outside traditional legal settings, for example in welfare offices or as patients in healthcare.[2]

Nonetheless, there remain unmet legal needs and the subject is under-researched in Finland. The reason for unmet legal needs may vary as there exist several different barriers such as costs or processual problems. Unmet legal needs can also occur in cases where a person does not understand his or her rights (lack of legal capability) or does not take action due to this or due to deficits in other areas such as socio-economic or other problems.[3]

Unmet legal needs may occur in traditional legal settings, but also to a high degree in areas where the best solution is not necessarily one involving the legal system. Research conducted among other things by the Institute of Criminology and Legal Policy (ICLP) has focused some of its research on these areas.

In Finland there have been several studies on barriers to achieving (legal) advice, representation or legal process (including ADR).[4] Costs of trials are for instance considered barriers to access to justice, and it indeed seems that the costs of trials have grown in the last decade.[5] Also, a small survey study (N=1004) by the Association of Finnish lawyers in 2018 studied how Finns perceive their legal expenses cover from insurance. The study found that almost half of the Finnish population (45 %) would be afraid of going to trial to defend their rights due to the costs of trial exceeding the legal expenses insurance cover. (Suomen Lakimiesliitto 2019).[6] There have been studies on the use of legal aid and barriers to it.[7]

However, it is not enough to take into consideration how legal authorities work and analyse data from courts or other legal authorities. There is a need for studies on legal needs that have a broader focus, that is, studies that focus on everyday legal problems that are experienced and settled outside the courtroom. Internationally, studies on legal needs have been carried out to inquire about people and their legal problems through surveys (OECD/Open Society Foundations 2019).

In Finland there have been two surveys on legal needs, Jaakkola (1993) (N=4333)[8] and Litmala (2000),[9] (N=1967). Both studies had a strict legal framing and focus. The studies specifically focused on problems for which the participants reached out to or contacted a lawyer or situations for which they seriously contemplated contacting a lawyer. In both surveys, 12 per cent of the respondents answered that they had experienced such a problem. Both studies inquired about problems relating to family, debt, crime, work, damage compensation, housing, consumer problems, tax, social security, and pensions. The studies also sought to find out if these problems related to conflicts or administrative decisions, such as tax returns, licenses or permits. According to the results, disputes or conflicts formed 68 per cent of the problems and 32 per cent were administrative issues. In the second survey (Litmala, 2000),[10] the most common problem was family-related issues or conflicts and the second most common problem was debt.

Additionally, Finland also participated in the Global Insights to Access to Justice Survey that was conducted in 101 countries.[11] The survey was conducted in the Autumn of 2017 using a probability sample of 1,014 adults age 18+ in the three largest cities of Finland – Helsinki, Espoo, and Tampere. However, the study does not include the entire Finnish population. As per the survey, 69 per cent of the Finnish population had experienced a legal problem in the previous two years. The most common problems were in the areas of housing, money and debt and the least common problems were pertaining to public services and consumer problems. When it came to legal capability, 67 per cent were aware of where to seek legal advice and information. When it came to problem resolution, 51 per cent felt they could get all the expert help they wanted or needed. 66 per cent were confident they could achieve a fair outcome and 68 per cent felt the process followed to resolve the problem was fair, regardless of the outcome.

11. PUBLIC LEGAL EDUCATION

The Finnish education system consists of nine years of compulsory comprehensive schooling (age 7-16 years), and subsequently children continue either in general or vocational upper secondary education. After the upper secondary schooling or vocational schooling, one can apply to study at University or apply to a university of applied sciences. The Finnish National Agency for Education is the national development agency responsible for basic education and general and vocational upper secondary education.

As part of the history and social studies syllabus, legal education is introduced in schools at the age of ten.[1] The aim of the studies is to teach how Finnish society works, the workings of a democratic society, the parliamentary system and Finnish elections, and the rights and duties of citizens, how to be an active citizen, and how to positively contribute to society. The compulsory studies cover some of these themes. At a later stage the focus is directed towards a broader understanding of societal structures and power relations, and this includes learning the basic tenets of a democratic society and its constitutional values. The teaching includes topics such as human rights and international agreements.