National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

The Constitution of Zambia was adopted in 1991. Since then, it has been amended in 1996, 2003, 2006, 2009 and 2016. As enshrined in the Constitution, the Republic of Zambia is a unitary, indivisible, multi-party and democratic sovereign State.[1] It is based on the values and principles of morality and ethics, patriotism and national unity, democracy and constitutionalism, human dignity, equity, social justice, equality and non-discrimination, good governance and integrity, and sustainable development.[2] Sovereignty is vested in the people of Zambia who shall exercise it directly or through elected or appointed representatives or institutions in accordance with the Constitution.[3]

Zambia follows the doctrine of separation of powers. The Constitution provides for the creation and existence of three main organs of the State that are fundamental pillars of the democratic governance of the country, namely the Executive, the Legislative and the Judiciary. The three branches and their functions include the following:

- The Executive, which includes the republican president, vice-president and ministers, supported by the civil servants. Its main function is enforcement of the law, with further reference to the rule of law;

- The Legislature or parliament whose main function is to make legislation;

- The Judiciary that is made up of the entire court system and is responsible for applying and interpreting the law.[4]

In 2019, the total population of Zambia was estimated at 17.4 million people.[5] Zambia comprises 72 ethnic groups. About 90% of the population fall into 9 major ethno-linguistic groups: the Nyanja-Chewa, Bemba, Tonga, Tumbuka, Lunda, Luvale, Kaonde, Nkoya and Lozi.[6] English is the official language of Zambia.[7] In terms of religion, the Constitution declares “the Republic a Christian Nation while upholding a person’s right to freedom of conscience, belief or religion.”[8]

The table below indicates the Zambia Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the last nine years in billions of US dollars (USD). The GDP in Zambia was worth 26.72 billion US dollars in 2018.[9]

| Year | Billions USD |

| 2010 | 20.27 billion USD |

| 2011 | 23.46 billion USD |

| 2012 | 25.50 billion USD |

| 2013 | 28.05 billion USD |

| 2014 | 27.15 billion USD |

| 2015 | 21.15 billion USD |

| 2016 | 20.95 billion USD |

| 2017 | 25.87 billion USD |

| 2018 | 26.72 billion USD |

According to the UNDP Human Development Report, “Zambia’s Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2018 is 0.591— which put the country in the medium human development category – positioning it at 143 out of 189 countries and territories”.[10] In 2018, life expectancy at birth in Zambia was 63.5 years (compared to 44 years in 2000, and 55.7 years in 2010). In 2018, the number of expected years of schooling was 12.1, with 7.1 mean years of schooling (compared to 5.9 mean years of schooling in 2000, and 6.6 in 2010). The gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP) was 3,582 (compared to 2,034 in 2000 and 3,1114 in 2010).[11]

The Gini coefficient reveals that income inequality has increased over the last years in Zambia, with a Gini coefficient standing at 0.57 in 2015 from 0.56 in 2010, 0.54 in 2003 and 0.49 in 1998.[12] As of 2015, 58% of Zambians earned less than the international poverty line of $1.90 per day (compared to 41% across Sub-Saharan Africa) and three quarters of the poor lived in rural areas.[13]

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of legal system

Zambia has a dual legal system comprising the Indigenous Customary Law Systems of the various ethnic groups in the country and the Received English System. This means Zambia decided at independence to use both customary law and statutory law. The latter is based on the English common law system and is dominantly applied in the higher courts of law (Subordinate Courts to the Supreme Court). However, the majority of Zambians still conduct their activities in accordance with and subject to customary law[1], but the term is used to cover a host of customary laws existing in different ethnic groups.[2]

2.2. The Zambian justice system

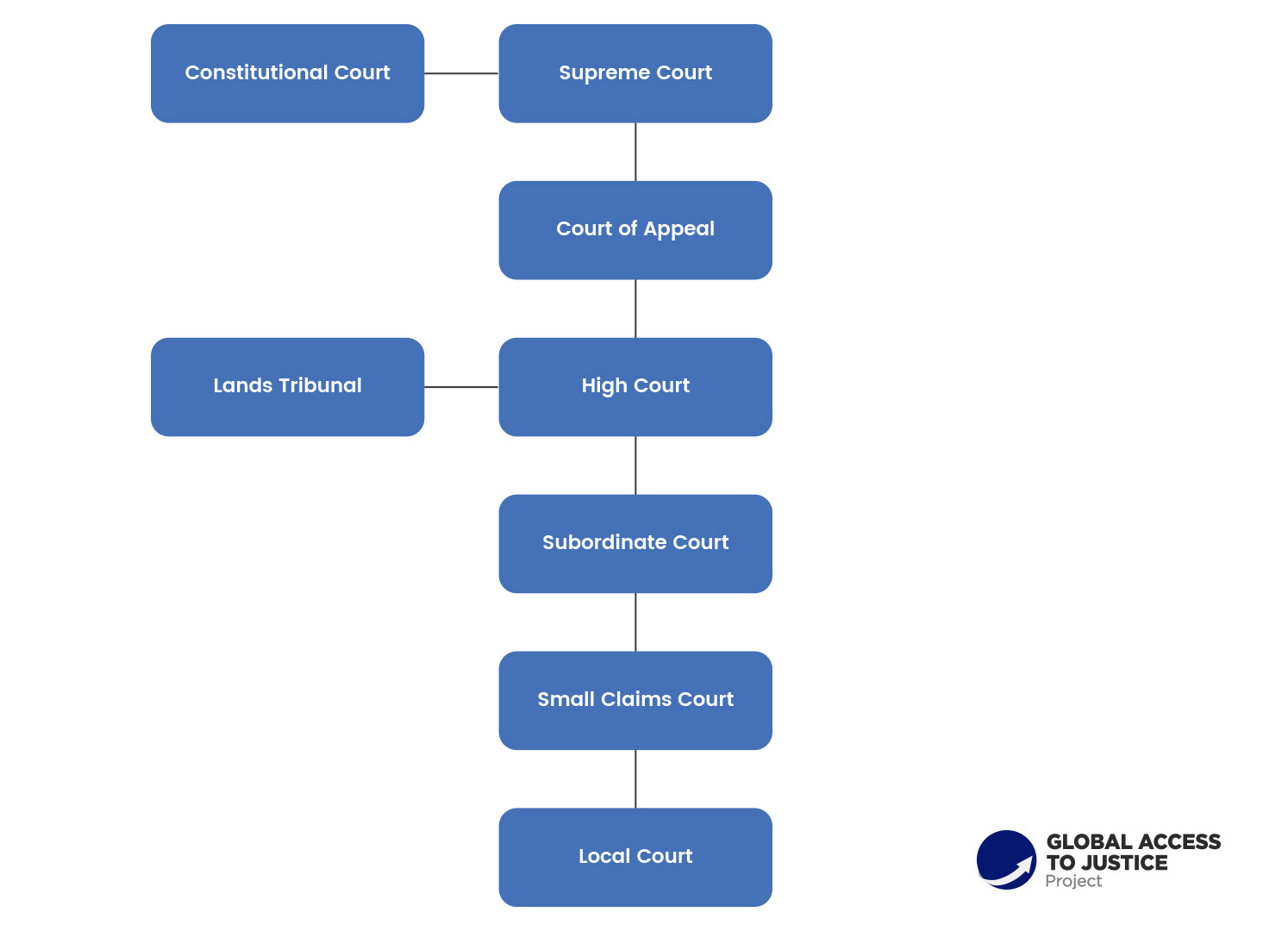

The Zambian judicial system is established in the Constitution of Zambia and comprises the following courts, namely the:

- Supreme Court;

- Constitutional Court;

- Court of Appeal;

- High Court;

- Subordinate Courts;

- Small Claims Court;

- Local Courts.

The first four are referred to as superior courts[3] while the last three are lower courts.[4] Chapter VIII of the Constitution of Zambia (Amendment) Act No. 2 of 2016 explains the judicial authority, hierarchy of the courts and independence of the courts.

The Supreme Court is the highest court of the country and the final court of appeal. The Supreme Court ranks pari passu with the Constitutional Court as the two highest courts in the civil court system. Other courts include the High Court and Subordinate Courts which both have original and appellate jurisdiction. The High Court also determines matters relating to the Bill of Rights as enshrined in the Constitution. Decisions from the Subordinate Courts are appealed to the High Court. Other courts include the Small Claims Courts which determine minor disputes by way of fast track procedure. There are also specialised tribunals such as the Lands Tribunal, Tax Appeals Tribunal, Competition and Consumer Protection Tribunal, these all rank the same as the High Court. The diagram below shows the present hierarchy of courts in Zambia (with the superior courts at the top of the list):[5]

Chart 01. Hierarchy of courts in Zambia

Local Courts are the majority among formal courts of law, closest to communities and the most accessible throughout the country. As at 2009, there were 469 Local Courts (144 Grade A Local Courts and 325 Grade B Local Courts), compared to about 54 Subordinate Courts.[6]

Local Courts are the majority among formal courts of law, closest to communities and the most accessible throughout the country. As at 2009, there were 469 Local Courts (144 Grade A Local Courts and 325 Grade B Local Courts), compared to about 54 Subordinate Courts.[6]

Local Courts are found at the lowest level in the hierarchy of formal courts of law. At least one Local Court is found in every chiefdom in rural areas. Local Courts are courts of first instance, dealing primarily with civil matters. They apply both statutory and customary law, provided that the customs applied are not contrary to the Constitution or any written law, the Bill of Rights, justice and morality. Customs that violate any rights in the Bill of Rights cannot be followed. As formal courts of law, they have enforcement powers (contrary to traditional courts). They rarely deal with criminal cases, except for cases of contempt of court. Any sentence of imprisonment by a Local Court must be confirmed by a Local Court authorised officer.[7]

Local Courts hear more cases than all other formal courts of law put together. In the year 2009, the Local Courts dealt with 111,510 civil cases and 13,076 criminal cases.[8] In other words, the Local Courts are the backbone of civil justice in the country. Cases relating to customary marriage and family matters, often including related property issues, make up a great part of the work of the Local Courts.

2.3. Traditional justice mechanisms in Zambia

Traditional courts in Zambia are not established by an Act of Parliament and are not part of the formal legal system. However, the current Constitution[9] recognises and encourages the promotion of traditional dispute resolution mechanisms that:

- Do not violate the Bill of Rights;

- Are consistent with other provisions of this Constitution or other written law; and

- Are not repugnant to justice and morality.

The composition of traditional courts varies from chiefdom to chiefdom and even from traditional court to traditional court depending on the level at which a particular court is operating at. The generally accepted composition includes the following:[10]

| Level of court | Composition |

| Traditional court at chief’s palace

|

· Chaired by chief’s representative

· Seven other senior village headpersons · Two to three community members |

| Zonal court

|

· Chaired by group (zonal) village headperson

· Six other village headpersons · One secretary |

| Senior headperson’s court

|

· Chaired by a senior village headperson

· Seven other village headpersons |

| Village court

|

· Chaired by vice village headperson

· Four village community members from the same village · One secretary |

In their work, traditional courts have limited jurisdiction. The most frequent types of cases handled by traditional courts include:

- Land and property matters: disputes on customary land, property sharing in relation to inheritance;

- Reconciliation between husband and wife, divorce, custody of children;

- Claim for bride price (lobola);

- The so-called ‘virginity damage’ cases (pregnancy of young girls);

- Conduct-related disputes: assaults, thefts, insults, defamation arising from allegations of witchcraft.

Although section 50 (1) of the Local Courts Act makes it an offence for any person who “pretends to exercise judicial functions as a Local Court Magistrate”, traditional leaders often see themselves as arbitrators rather than mediators or conciliators, meaning that they decide the case after hearing parties.

Community members are not forced to strictly follow the hierarchy, one may go straight to the zonal or traditional court at chief’s palace without going through the village court or any other court. In principle, any party in a matter dealt with by a traditional court has the right to take her/his case to the Local Court, regardless of the outcome at traditional court level.

2.4. Structure of the legal profession

The Legal Practitioners Act[11] Chapter 30 of the Laws of Zambia provides the standing or precedence of legal practitioners at the bar in Zambia as follows: the Attorney-General; the practitioners who had filled the office of Attorney-General, in the order of the dates of their appointment as Attorney-General; the Solicitor-General of Zambia; the practitioners who had filled the office of Solicitor-General of Zambia, in the order of the dates of their appointment as Solicitor-General of Zambia; all State Counsel for Zambia, in the order of the dates on which the dignity of State Counsel for Zambia was conferred upon them; and all other practitioners according to the order of entry of their respective names on the Roll. Therefore, the standing or precedence of practitioners in Zambia relates to the seniority in ranking of practitioners, rather than power or rights bestowed. However, this seniority of practitioners often requires that they have priority of audience during court sessions and cause listing of matters as they are deemed to have more practical experience.

Furthermore, legal practitioners that have completed an undertaking as to practical experience, of active employment for a continuous period of, or for periods amounting in all to, three years, as a legal practitioner, and certified as being satisfactory[12], may set up a legal practice or open a law firm or become partner or managing partner in a law firm. Therefore, non-lawyers not admitted as practitioners are prohibited from setting up or managing a law firm in Zambia.

As of April 2019, there were 1,265 legal practitioners registered at the Law Association of Zambia (LAZ) and holding a valid practice certificate, which makes a ratio of 1 legal practitioner to 13,439 persons. Most legal practitioners that are in private practice are concentrated in Lusaka and in a few other major towns in Zambia (primarily Kitwe and Ndola in Copperbelt province, to a lesser extent in Kabwe, Livingstone and Chipata in Central, Southern and Eastern provinces respectively), focusing on court work and providing legal services that most citizens cannot afford.

Fees charged by legal practitioners are generally not affordable for the general population, considering the poverty levels in Zambia.

2.5. Legal representation in Zambia and other legal services provided under legal aid

The Zambian judicial system requires parties appearing in superior courts to be represented by legal counsel, particularly in criminal matters. Matters before the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court, require that parties are represented, however parties without access to a lawyer may be directed to the Legal Aid Board[13] or have this right waived and may appear in person. Lower courts such as the Subordinate Court, allow for parties to appear in person or to be represented. The Local Court Act prohibits use of legal representation, except in specified circumstances, such as criminal charges[14].

In addition, the National Legal Aid Policy[15] creates a framework for non-legal practitioners to deliver legal aid services in Zambia. This includes paralegals and legal assistants (law degree holders) with a requirement that they register at the Legal Aid Board for purposes of providing legal aid. In 2019, the number of active paralegals was in the range of 500 countrywide.

Paralegals are now organised in three levels whereby qualification requirements match the various levels of specialisation. In July 2018, the Technical Education, Vocation and Entrepreneurship Training Authority (TEVETA) approved the newly established three-level training scheme for paralegals in Zambia, in line with the National Legal Aid Policy.

The types of legal aid services that paralegals provide differ depending on the level of the paralegal training completed as follows:[16]

| Levels | Types of legal aid services provided |

| Level 1 paralegals | · Full spectrum of primary legal aid services (as per level 2 paralegals)

· Legal assistance |

| Level 2 paralegals | · Full spectrum of primary legal aid services:

· Legal education · Legal information · Legal advice · Orientation, referrals and accompaniment · Alternative dispute resolution (excluding court-annexed mediation) |

| Level 3 paralegals | · Primary legal aid services restricted to:

· Basic legal education · Legal information · Orientation, referrals and accompaniment · Mediation on less complicated matters (and excluding court-annexed mediation) |

As per level 1 paralegals, legal assistants (law degree holders) can provide the full spectrum of primary legal aid services as well as legal assistance.

Representation in court by paralegals or legal assistants is not permitted in Zambia.

2.6. Judges and magistrates

The Judicature Act[17] of December 1994 provides for the independence of the Judiciary. The process of ensuring the institutional independence of the Judiciary that had begun in 1997 is now said to be complete, with full separation from the main civil service, so that support staff are now employed independently by the Judiciary.[18] The 2016 Constitution provides for both the functional and financial independence of the Judiciary.[19]

Furthermore, the Constitution of Zambia 2016 provides for the appointment of judges (including the Chief Justice, Deputy Chief Justice, President of the Constitutional Court, Deputy President of the Constitutional Court, and other judges) by the President, on the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission and subject to ratification by the National Assembly.[20] The tenure of office of judges is until retirement age as stipulated in the Constitution, with mandatory retirement at seventy years or at sixty-five years where the judge retires from office.[21] A judge who has retired is not eligible for appointment as a judge. However, in the case of the Chief Justice and President of the Constitutional Court, these shall hold office for not more than ten years and may, thereafter, continue as a judge of the Supreme Court or Constitutional Court.

The Judicial Service Commission is responsible for the recruitment, appointment and disciplinary functions in relation to all but the senior levels of the Judiciary, also making recommendations to the President regarding the appointment of judges. A judge shall be removed from office on the following grounds: a mental or physical disability that makes the judge incapable of performing judicial functions, incompetence, gross misconduct or bankruptcy. The removal of a judge may be initiated by the Judicial Complaints Commission or by a complaint made to the Judicial Complaints Commission, based on those grounds.[22] The Judicial Service Commission may transfer judges as and when required for purposes of filling vacancies in different parts of the country or for purposes of rotating judges.

In 2010, the number of judges and magistrates were as follows:[23]

| Court level | Location / numbers | Establishment | Filled positions | Number of women judges/magistrates |

| Supreme Court | 1 | 11 | 10 | N/A |

| High Court | 5 | 50 | 31 | 17 |

| Industrial Relations Court | 2 | 5 | 4 | N/A |

| Subordinate Courts | 54 | 251 | 156 | 29.6%

(based on statistics from four provinces) |

| Local Courts | 469 | 1,061 | 680 |

In 2010, 55% of the high court judges were women (nationwide), and 29.6% at Subordinate Court level (based on statistics from four provinces).[24]

At Local Courts level, most magistrates used to be men but the situation has been changing over time. In 2012, during a scoping mission carried out by the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) to 10 different Local Courts, 33% were female magistrates.

2.7. Public prosecutors

The National Prosecution Authority (NPA) is an autonomous body established by the National Prosecution Authority Act No. 34 of 2010, which transformed the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP) into an independent National Prosecution Authority. It is headed by the Director of Public Prosecutions, who is appointed by the President subject to ratification by Parliament. Article 180 of the Constitution creates the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The National Prosecutions Authority comprises of a Board of the Authority as established under the National Prosecutions Authority Act of 2010, appointed by the Minister of Justice. Among its functions as provided in the said Act, is to appoint a Chief State Advocate, Deputy Chief State Advocates, State Advocates and other staff of the Authority.[25] In addition, the Director of Public Prosecutions may, by Gazette notice, appoint a person as a prosecutor for prosecution of crimes under specific Acts only, or for prosecution of any offence under any Act. As civil servants or government workers, prosecutors are subject to conditions of employment of civil service in Zambia, which entails that they are permanent and pensionable employees. The delegated prosecutorial powers for a prosecutor who resigns or reaches retirement age automatically seize. The conditions of civil service or government employees provide that employees may retire from employment at the age of sixty-five years or they may opt for an early retirement at the age of fifty-five years.

With the enactment of the National Prosecution Authority Act, all criminal prosecution functions were vested in the National Prosecution Authority to prosecute all criminal matters. This entailed that all law enforcement agencies having a criminal prosecution function such as Zambia Police, Department of Immigration, Department of National Parks and Wildlife and other law enforcement agencies, would be regulated by the National Prosecution Authority, with the Authority having an oversight role over all prosecutions. As of December 2019, the National Prosecution Authority comprised of 64 State Advocates, these are prosecutors who have been admitted as legal practitioners. The National Prosecution Authority also comprises of public prosecutors who are not admitted as practitioners but possess legal training such as a Law Degree and/or prosecutors’ certificate. Overall, the National Prosecution Authority has about 466 prosecutors.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

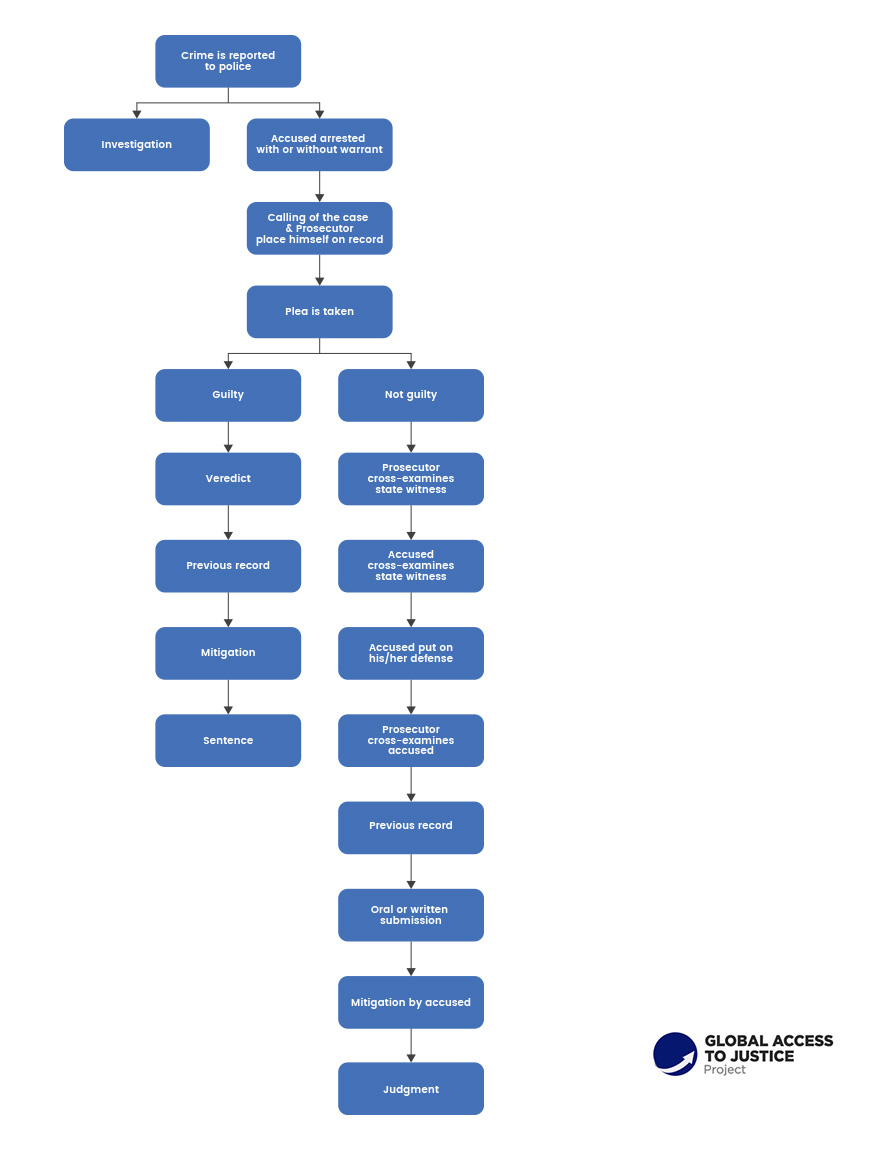

3.1. Criminal Procedure

In Zambia the procedure used during criminal trials is based on the procedure followed in English courts, however, the Criminal Procedure Code[1] is the most important statute in the criminal justice process, setting out the specific procedure to be used for any given case.

Article 18(1) of the Bill of rights in the Constitution of Zambia provides for the right to secure protection of the law. It demands, among other things, that every person facing criminal charges should be prosecuted on that charge within a reasonable time. In Zambia, criminal proceedings may be instituted through an arrest with or without a warrant:

- Arrest wihtout a warrant: police officers may arrest without a warrant for any of the listed offences and cognisable offences[2] as provided in the Penal Code Act Chapter 87 and in the Criminal Procedure Code Chapter 88 of the Laws of Zambia. Here having received a report of an offence, the police may investigate and arrest a person suspected of commission of the offence;

- Arrest with a warrant: furthermore, proceedings may be instituted either by the making of a complaint to a magistrate or by the bringing before a magistrate. Therefore, any person who believes from a reasonable and probable cause that an offence has been committed by any person may make a complaint thereof to a magistrate having jurisdiction. The magistrate may draw up a formal charge and summons for a warrant of arrest, which will be issued.

In addition, private person may institute criminal proceedings by making a private citizens arrest without a warrant and take such person or suspect to a police officer, or, in the absence of a police officer, shall take such person to the nearest police station. Upon arrest a suspect or accused person should be informed in a language that they understand the reasons for the arrest and offence they are being charged with.[3] In the instance where the arrested person is a juvenile it is the duty of the police to communicate to the juveniles family or guardians of the arrest and further endeavour to put the juvenile through diversion.

Investigations of the case or complaint by the police begin when a report or complaint or warrant for arrest is received. Once an arrest is made with or without a warrant the police may investigate the case further, however detention of a suspect in police custody should not be for a period exceeding twenty-four hours[4], following which police bond may be given, for offences that are bailable. Police bond is a written promise by the accused that s/he will appear in court or at the police station as and when required. Further conditions of the bond may be made by the police. Usually police bond is given at the police station, authorised by the Officer-in-Charge of the station. During this time the case or file/docket is sent to the Zambia Police legal department for processing where it is then forwarded to the National Prosecutions Authority for indictment and court date is set, which is communicated to the accused person. However, if the National Prosecutions Authority is of the view that the case does have sufficient evidence to warrant an indictment, it is sent back to the arresting police station through the Zambia Police legal department, for further investigation or collection of evidence. There is no provision in the law that stipulates a time limit for completing of police investigations, however there have been decided cases that stipulate that proper investigations should be undertaken by police as they have the duty to investigate cases.[5]

Once an indictment is drawn up by the National Prosecutions Authority, a court date for the commencement of trial is set, which is communicated to the accused and complainant. On this date the matter will be called for hearing, both the accused and complainant may be before court. Generally it is a requirement that the accused person should be before court during trial as all evidence taken in any inquiry or trial shall be taken in the presence of the accused, or, when her/his personal attendance has been dispensed with, in the presence of her/his advocate (if any).[6] Where the accused is not in attendance, the court may set another date for hearing. However, when the offence with which the accused is charged is punishable only by fine or only by fine and/or imprisonment not exceeding three months, the court may dispense with the personal attendance of the accused, if s/he pleads guilty in writing or appears by an advocate[7]. Where the complainant, having had notice of the time and place appointed for the hearing of the charge, does not appear, the court shall dismiss the charge, unless, for some reason, it shall think it proper to adjourn the hearing of the case until some other date.[8]

During this period and dependent on the offence the accused is charged with, the accused may be held on remand during trial for non bailable offences, or in instances where police bond was not granted during arrest, the accused would attend court and remain on remand. However, where police bond was not granted, and the offence committed is a bailable offence, the accused may apply for bail during trial. On the other hand, the accused may have been granted police bond and in this instance attends court from her/his place of residence. Once trial commences the police bond may be extended to be a bail during trial.

Where both parties are present for hearing, trial will commence with the charge, statement and particulars of offence being read out to the accused in a language s/he understands. The accused is then asked to confirm her/his particulars including name and address. Following this the court takes a plea from the accused of guilty or not guilty after the reading of the charge. Where there is more than one count, each count is read to the accused and plea taken.[9] Where the accused enters a plea of guilty or admits to the truth of the charge, her/his admission shall be recorded, as nearly as possible, in the words used by her/him, and the court shall convict her/him and pass sentence upon or make an order against her/him, unless there shall appear to it sufficient cause to the contrary.[10] Where the accused pleads not guilty or does not admit to the charges, the court will proceed to hear the prosecution’s case with the complainant and witnesses and other evidence, if any. If the prosecution is not ready to proceed the court may adjourn and set a date for trial during. Once the prosecutions have completed giving their evidence, the accused person or her/his advocate may put questions to each witness produced against her/him.

If, at the close of the evidence in support of the charge or prosecution, it appears to the court that a case is not made out against the accused person sufficiently to require her/him to make a defence, the court shall dismiss the case, and shall forthwith acquit her/him[11] and enter a finding of no case to answer. At the close of the evidence in support of the charge or prosecution, if it appears to the court that a case is made out against the accused person sufficiently to require her/him to make a defence, the court shall again explain the substance of the charge to the accused and shall inform her/him that s/he has the right to give evidence on her/his own behalf and that, if s/he does so, s/he will be liable to cross-examination, thus putting the accused on her/his defence. If during her/his defence the accused introduces new evidence the prosecution will be given the option to give evidence in reply[12]. Having heard both sides the court will make a decision on whether to sentence or acquit the accused person.[13] See below an organisational chart indicating the main steps in criminal proceedings:

Chart 02. Main steps in criminal proceedings

It should be noted, however that criminal law or procedure in Zambia does not stipulate the duration of remand of accused persons during trial or the time limit for completing a criminal trial. Trial is dependent on many factors affecting the prosecution, such as availability of evidence, the courts diary in relation to scheduling of dates for trial, attendance of witnesses for or against the accused. Due to these factors among others, delays are often experienced in the prosecution of criminal cases.

It should be noted, however that criminal law or procedure in Zambia does not stipulate the duration of remand of accused persons during trial or the time limit for completing a criminal trial. Trial is dependent on many factors affecting the prosecution, such as availability of evidence, the courts diary in relation to scheduling of dates for trial, attendance of witnesses for or against the accused. Due to these factors among others, delays are often experienced in the prosecution of criminal cases.

The Zambia Human Rights Commission outlined the issues of prolonged stays in remand and the delays in court processes. According to the Human Rights Commission, close to 50% of accused persons spend at least six month in remand, and more than 13% spend over two years before their cases are concluded in court.[14] During the 2017 Universal Periodic Review, the Government of the Republic of Zambia accepted five out of six recommendations for Sustainable Development Goal 16.3 that relate to the rule of law and access to justice, including recommendations to “take appropriate steps to reduce long terms of preventive detention” and to “guarantee the rights of detainees”.[15]

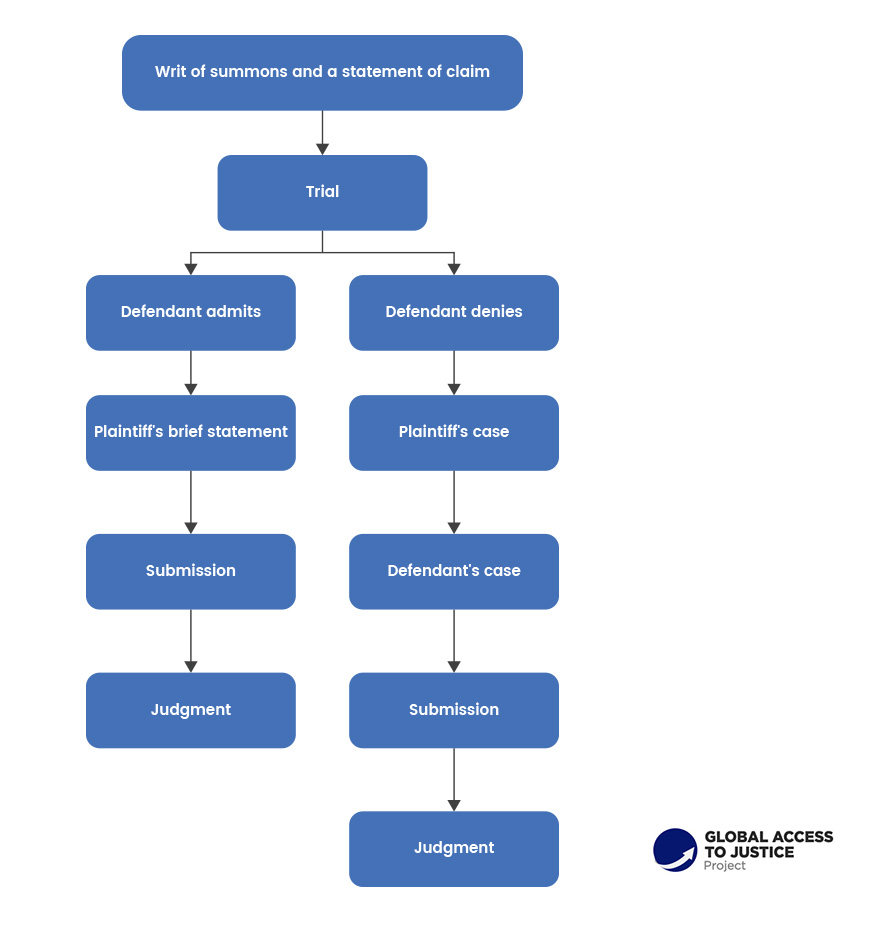

3.2. Civil Procedure

Civil proceedings in Zambia is a primary responsibility of the parties involved in a case, except for the Commercial Court, a division of the High Court which is driven by a judge. Actions are commenced by a party instituting an action and seeking relief from a particular court. Depending on the court, this could be by way of writ of summons, notice of claim, notice of complaint or default writ of summons, originating notice of motion, petition or originating summons, or appeal. The originating documents set out the claimant’s claim in brief and the relief sought. A defendant is expected to prepare a statement of defence in response to the claim. Directions are usually given by the judge setting out the manner in which the pleadings will be settled, how discovery and inspection will proceed, and when and how the trial is to proceed. See below an organisational chart illustrating the main first instance procedure in civil matters:

Chart 03. Main first instance procedure in civil matters

As earlier stated, the Commercial Division of the High court has a peculiar difference with the procedure in other divisions which adopt a party-driven procedure. The Commercial Court is judge-driven. As such, once a claim is lodged in the High Court, the judge sets up a scheduling conference where the timelines for filing of the pleadings is agreed with the parties. The judge then issues and motions the agreed schedule by way of order for directions. The judge will then proceed to hold status conference until the case is set down for hearing. Unlike other civil proceedings in Zambia, the Commercial Court requires written witness statements to be filed into Court and exchanged by the parties prior to the trial. The underlying framework is that there should be no trial by ambush as every litigant has a right to have notice of the matter that will arise at trial.

As earlier stated, the Commercial Division of the High court has a peculiar difference with the procedure in other divisions which adopt a party-driven procedure. The Commercial Court is judge-driven. As such, once a claim is lodged in the High Court, the judge sets up a scheduling conference where the timelines for filing of the pleadings is agreed with the parties. The judge then issues and motions the agreed schedule by way of order for directions. The judge will then proceed to hold status conference until the case is set down for hearing. Unlike other civil proceedings in Zambia, the Commercial Court requires written witness statements to be filed into Court and exchanged by the parties prior to the trial. The underlying framework is that there should be no trial by ambush as every litigant has a right to have notice of the matter that will arise at trial.

3.2.1. Procedures for urgent matters

Under both civil and criminal procedure, the law allows for specific procedures to be utilised for matters of urgency that may arise. For instance, under civil procedure specific procedures that can be utilised include interim injunctions which are an order issued by a court of competent jurisdiction restraining a party from doing or committing certain acts or an order issued by a court compelling a party to take certain steps. The court may issue a prohibitive injunction to restrain a party from doing anything which continues the breach complained about, or a mandatory injunction to compel a party to perform a certain action to correct the wrong complained about. However, the order compelling or restraining will always relate to or will be issued in connection with ongoing litigation. In other words, the right to obtain an interim injunction is merely ancillary and incidental to a pre-existing cause of action against the defendant. The essential nature or character of an interim injunction is that it is a temporary measure intended to maintain or preserve the status quo pending determination of the disputed rights of the parties at trial, which may require urgent action.

Another urgent procedure that can be implored is a stay of execution which can be used or applied for where the court has given its judgement on a case but one party to the case would like to stay the execution of the judgement given, either to allow for appeal or review of the decision of the court.

Other civil procedures relating to urgency include caveats in land matters. A caveat is a statutory notice that is registered against a property. It serves as a notice that the person lodging the caveat (‘the caveator’) has an interest in the land. Further the law provides for interim attachment of property which is a provisional or temporary relief which allows the plaintiff to attach the defendant’s property, whilst a court action progresses. All these measures and many others can be used under civil procedure in urgent matters.

Under criminal procedure, procedures such as Habeas Corpus, can be utilised as matter of urgency. This is a court order that commands an individual or a government official who has restrained another to produce the inmate/suspect at a designated time and place so that the court can determine the legality of custody and decide whether to order the release of the inmate/suspect. Under gender-based violence cases, orders such as protection orders, or restraining orders can be utilised as a matter of urgency, to protect a complainant or victim of violence, during the determination of the case.

General conditions attached to these procedures include, that the applicant of the urgent procedure shows the court the urgency of the matter or request, also that without it being granted the effect or consequence would be detrimental to the applicant and lastly that there is an eminent threat of danger/violence in the case of criminal matters.

3.2.2. Alternative dispute resolution

Alternative dispute resolution before or during court proceedings is not obligatory and parties may choose to use alternative dispute resolution before going to court. There has been increased use of arbitration and mediation by litigants in Zambia. Arbitration is commonly used in commercial matters and its proceedings are governed by the Arbitration Act No. 19 of 2000. The Arbitration Act incorporates the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law and the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitration Awards. The rule is that if the parties have agreed to have an arbitration clause in the agreement, then the Zambian courts have no jurisdiction to adjudicate on the matter. The court, however, can grant an interim relief to facilitate an arbitral tribunal discharging its functions. Mediation in Zambia is court-annexed (see further details below – 3.3 Alternative dispute resolution).

Most specialised contracts prefer arbitration because it is quicker and the parties can get an expert in the subject area of the contract to arbitrate. There are two recognised arbitral institutions, namely, the Zambia Association of Arbitration (ZAA) and the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators Zambia Branch (CIArbZB). Arbitration awards are conclusive and final, thus a party cannot appeal against an arbitration award. On the other hand, mediation agreements or settlements need to be registered in the courts for them to be recognised as binding.

During formal civil legal proceedings, courts in Zambia may also attempt to reconcile parties, for example in marital disputes, trying to make them arrive at a settlement which is agreed upon by the parties themselves before the court pronounces its judgment. Hence, the courts sometimes on their own motion refer parties for court-annexed mediation where they are encouraged to discuss fully and reach an agreement that ensures a “win-win” situation.[16] Furthermore, it is common for Local Courts in certain cases (apart from what is provided for in intestate succession cases[17]) to give returnable dates to the parties (where parties will have to come back and appear before the court at a certain date to report on progress made in implementing the Local Court judgment) in a matter that has been concluded to ensure the court orders are obeyed. It is also a way of monitoring the execution of judgments passed by the Local Courts.

3.3. Alternative dispute resolution (including simplification of law and by-passing legal process)

Compulsory diversion of disputes in Zambia is called court-annexed mediation, which was established in Zambia by the High Court (Amendment) Rules[18] which came into force in 1997. Subsequently, a group of mediators was trained for purposes of taking conduct of some of the matters that were before the High Court. Court annexed mediation is invoked by the judge’s own motion – the judge may decide to send the case for mediation before hearing commences. The judge’s authority to refer the matter to mediation is found in Rule 4 of the High Court (Amendment) Rule.[19] The Rule provides as follows:

“Except for cases involving constitutional issues or the liberty of an individual or an injunction or where the trial judge considers the case to be unsuitable for referral, every action may, upon being set down for trial, be referred by the trial judge for mediation and where the mediation fails the trial judge shall summon the parties to fix a hearing date. The referral order shall be in form 28A in the First Schedule, set out in the Appendix to these Rules”.

It is clear from the rules that it is the judge and not the parties who makes the decision whether or not to refer the matter to mediation. Therefore, court-annexed mediation is not voluntary since parties may have no choice but to oblige to the court’s order referring the matter to mediation. In Zambia, although parties are obliged to attempt mediation once the judge has referred the matter to mediation, they are not compelled to arrive at a settlement, they are merely compelled to attend the mediation because the referral order is an order of the Court. Any matter referred to mediation, if not settled within sixty days of the referral to the mediator, is taken back to the trial judge.

Apart from court-annexed mediation, as already discussed above, there is always chance for what is called party-driven mediation which may happen prior to or during litigation. This is known as non-Court annexed mediation. It is also possible that during proceedings, the parties may request the court to be given time to try and resolve the matter outside court. If such an attempt fails to resolve the matter, the parties will go to court again.

With respect to arbitration, as described above, parties may only go to arbitration if they have voluntarily agreed that their dispute will be resolved through arbitration. The court does not sanction arbitral proceedings save for when a matter is before the court and the parties had agreed to refer the matter to arbitration.[20] As per the Arbitration Act, an award made by an arbitrator or arbitration tribunal pursuant to an arbitration agreement is, subject to the right of either party to challenge the award by way of any process specified under the Act, final and binding on both parties and on any person claiming through or under them.

Out of court settlement mechanisms are independent of government machinery, these are initiatives (voluntarily or otherwise compulsorily) undertaken by the parties to avoid the expenses that arise from litigation as well as to trickle down on the timeframe by which cases in the courts of law take to be disposed. The costs are of such mechanisms are therefore borne by the parties to the dispute. The government plays a hands-off approach in such instances.

Unlike litigation, non-court annexed mediation in Zambia has been practiced even before, during and after colonialism. Without dismissing the limitations or disadvantages to non-court annexed mediation, it still remains the most preferred means of alternative dispute resolution in Zambia for most citizens in both rural and urban areas because of a number of reasons[21] including, but not limited to the following:

- Mediation reverberates with traditional ways of resolving disputes. Even among the elite, most individuals, families and communities still prefer indigenous conflict resolution processes such as mediation because it is based on cultural concepts, values, and procedures that are understood and accepted which promotes consensus-building, social bridge reconstructions and enactment of order in the society;

- Being relatively inexpensive, mediation is seen as a less expensive route to follow for dispute resolution compared to other modes dispute resolution such as taking a case through trial which is an expensive scheme. Besides, most claims in civil cases especially among low income earners are relatively low compared to what would be spent in litigation;

- Disputes are processed more quickly and resolved earlier avoiding congested court schedule and sessions. To the contrary, mediation can be easily scheduled any time at the mutual convenience of the parties and the mediator, and can take place in a variety of locations;

- Mediation is user friendly and relatively flexible. Mediation sessions use a language both parties to the dispute are familiar with facilitated by familiar personalities that have been accepted by both parties. There are higher chances of parties coming up with multiple and flexible possibilities for resolving a dispute, with the process being under their control and to their satisfaction, unlike in a case filed in court, where the parties might obtain an imposed resolution by the judge which may leave both parties to the dispute unhappy.

Finally, in criminal proceedings, the Criminal Procedure Code opens the possibility for Subordinate Courts to use reconciliation in settling in an amicable way, proceedings for assault and certain other offences of a personal or private nature. Remedy will be in the form of compensation or other terms approved by the court.[22]

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

The foundation for access to justice and fair trial in Zambia stems from the Constitution as provided in Article 18 of the Bill of Rights. The Article enshrines the right to a fair hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial court established by law. Based on principles of equality before the law and the presumption of innocence, the Constitution provides for a number of guarantees necessary for the defence of anyone charged with a penal offence (Article 18 of the Bill of Rights) as well as protection from discrimination (Article 23 of the Bill of Rights) and protection from inhuman treatment (Article 15 of the Bill of Rights).

In 2019, Zambia was ranked number 92 (out of 126 countries surveyed) in The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, which measures the following eight parameters on the rule of law: constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice and criminal justice.[1] In Sub-Saharan Africa, Zambia was ranked number 12 (out of 30 countries surveyed).

The Government has committed itself to enhancing equal access to justice particularly for the poor and vulnerable people, as part of its efforts to observe the rule of law and adhere to human rights, in line with the National Vision 2030 and the Seventh National Development Plan 2017-2021 of the Republic of Zambia. Under that framework, the Government sees legal aid as a central element to enhance access to justice. In particular, the Seventh National Development Plan is based on the adoption of the National Legal Aid Policy, as well as the strengthening of the Judiciary and the National Prosecution Authority, and the enhancement of the parole system.[2]

In the National Legal Aid Policy, the Government recognises access to justice as a fundamental human right in itself and essential for the protection and promotion of all other civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights. It also recognises that enhancement of access to justice necessitates effective provision of legal aid, with legal aid encompassing the provision of legal education, information, advice, assistance, representation and mechanisms for alternative dispute resolution (see further details below – 5.1. History of legal aid) with further reference to the United Nations Principles and Guidelines on Access to Legal Aid in Criminal Justice Systems adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December 2012.[3]

The Ministry of Justice has overall responsibility for access to justice policy in Zambia. The Judiciary also plays a key role through the Communication, Cooperation and Coordination Initiative (CCCI) platform, where justice institutions and other key justice stakeholders meet on a regular basis as Chapters at district level in the provinces. In their meetings, CCCI Chapters share information, discuss and address selected issues affecting case flow and justice delivery, and improve collaboration and engagement among institutions with the ultimate objective of improving efficiency in the justice sector. The Ministry of Justice is responsible for the overall management and monitoring of CCCI Chapters, while the Judiciary chairs each Chapter at district level. In addition to the Judiciary, CCCI membership includes the Zambia Correctional Service, the Zambia Police Service, the National Prosecutions Authority, the Legal Aid Board, the Anti-Corruption Commission, the Drug Enforcement Commission, the Immigration Department, the Social Welfare Department, the Ministry of Health and other institutions. CCCI Chapters also include civil society organisations working in the justice sector. CCCIs are currently supported under the Programme for Legal Empowerment and Enhanced Justice Delivery in Zambia (PLEED) (supported by the European Union and the Federal Republic of Germany).

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

5.1.1. Legal Aid Act

The right to legal aid was first recognised under the Legal Aid Act enacted in 1967, amended in 1972 and 2000, providing for the “granting of legal aid in civil and criminal matters and causes to persons whose means are inadequate to enable them to engage practitioners to represent them (…)”.[1] The legal aid scheme was placed under the Directorate of Legal Aid at the then Ministry of Legal Affairs (who later became the Ministry of Justice).

A significant restructuring of the national legal aid system occurred with the Legal Aid (Amendment) Act of 2005, establishing the Legal Aid Board (taking over from the Directorate of Legal Aid) as a separate statutory body with the mandate to provide and administer the legal aid system.[2] The Legal Aid Board became operational in 2008.

5.1.2. National Legal Aid Policy

The following major reform occurred in 2018 with the adoption by the Government of Zambia, of the National Legal Aid Policy with the objective to ensure efficient and effective delivery of legal aid services to the poor and vulnerable people in Zambia.

The National Legal Aid Policy is the product of contributions and consultations with various stakeholders that the Ministry of Justice and the Legal Aid Board have engaged since 2009. In 2012 and 2013, a first draft National Legal Aid Policy was formulated by a multi stakeholder Committee established by the Minister of Justice and chaired by the Legal Aid Board. Building on this process, a Technical Working Group was appointed in 2016 by the Ministry of Justice with the task of completing the development of the draft National Legal Aid Policy. The process was led by the Legal Aid Board and involved the Ministry of Justice, the Law Association of Zambia, the National Legal Aid Clinic for Women-NLACW and the Paralegal Alliance Network-PAN, with further engagement with Cabinet Office on the revised draft. It also involved advisors from the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) who assist the development of the policy, legislative and regulatory framework on legal aid in Zambia, under the PLEED Programme. The process culminated into broad consultations on the draft National Legal Aid Policy carried out with all relevant ministries, the Judiciary and other state institutions, the Law Association of Zambia, universities and other higher educational institutions, civil society organisations and other relevant stakeholders at national and provincial levels.

Based on a holistic approach to legal aid, the National Legal Aid Policy contains the following key innovations:

- Expand the mandate and functions of the Legal Aid Board: The National Legal Aid Policy recognises the duty and responsibility of the State to provide for legal aid. It expands the mandate and functions of the state Legal Aid Board to include not only the provision and administration of legal aid, but also the coordination, regulation and monitoring of the legal aid system.

- Broaden the definition of Legal Aid: The National Legal Aid Policy widens the scope of legal aid services for the provision of the full spectrum of legal services to the poor and vulnerable people. As a result, services consisting of legal education, legal information, legal advice and mechanisms of alternative dispute resolution expressly fall within the scope of the legal aid system in Zambia, in addition to legal assistance and representation in court.

- Recognise paralegals and legal assistants: The National Legal Aid Policy creates a framework for non-legal practitioners to deliver legal aid services in Zambia. This includes paralegals and legal assistants (law degree holders) with a requirement that they register at the Legal Aid Board for purposes of providing legal aid. The quality assurance framework for paralegals will be further developed by a multi stakeholder Paralegal Standing Committee to be constituted by the Legal Aid Board.

- Involve civil society organisations and university law clinics: The National Legal Aid Policy officially recognises civil society organisations and university law clinics as legal aid service providers, subject to their accreditation at the Legal Aid Board. Civil society organisations and university law clinics will complement services provided by the provincial and district offices of the Legal Aid Board countrywide, whereby supporting the geographical expansion of the legal aid system in Zambia.

- Establish a mixed legal aid delivery system: The National Legal Aid Policy establishes a mixed legal aid delivery system involving complementary legal aid service delivery models based on cooperation and engagement between state and non-state legal aid service providers. This includes the continued establishment of legal desks based at police stations, correctional facilities and courts of law (the ‘Legal Services Units’), where legal services are jointly provided by the Legal Aid Board and civil society organisations, involving the various categories of legal aid staff with paralegals, legal aid assistants and legal practitioners from the Legal Aid Board.

- Strengthen the role of the legal profession in the delivery of legal aid services: The National Legal Aid Policy promotes the establishment of a comprehensive pro bono framework for an increased number of legal practitioners to provide legal aid services on a pro bono basis.

- The right to be informed on legal aid: The National Legal Aid Policy establishes a duty for judges, judicial officers, correctional facility officers, police officers, prosecutors and any other law enforcement officers to inform persons on their right to apply for legal aid and the availability of legal aid services. With regard to suspects or accused persons, the National Legal Aid Policy requires such information to be provided prior to any questioning or at the time of deprivation of liberty. It further requires police officers, correctional facility officers and any other law enforcement officers to facilitate and assist detained persons requesting to contact the Legal Aid Board to apply for legal aid. This should ensure that legal aid becomes readily accessible at all stages of the justice system enabling individuals to claim their rights.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

5.2.1. Bill of Rights

The foundation for legal aid in Zambia stems from the Constitution as provided in Article 18 of the Bill of Rights. In particular Article 18 provides that:

“(2) Every person who is charged with a criminal offence – (…) (d) shall unless legal aid is granted to him in accordance with the law enacted by Parliament for such purpose be permitted to defend himself before the court in person, or at his own expense, by a legal representative of his own choice; (…)”.

Subsequent legislation, in this case the Legal Aid (Amendment) Act No. 19 of 2005 (hereinafter referred to as the “Legal Aid Act”), provides further guidance on legal aid provision.

5.2.2. Types of legal services provided by the Legal Aid Board

Section 3(1) of the Legal Aid Act defines the types of legal services provided by the Legal Aid Board as:

- “the assistance of a practitioner including all such assistance as is usually given by a practitioner in the steps preliminary or incidental to any proceedings or in arriving at or giving effect to a compromise to avoid or bring to an end any proceedings; and

- representation in any court.”

Legal aid under the Legal Aid Act can include not only all assistance given preliminary or incidental to actual proceedings, but also assistance given out of court to avoid proceedings by arriving at a compromise or giving effect to any such compromise. However, the definition of legal aid in the Legal Aid Act lacks clarity, since it does not specifically mention primary legal aid services consisting of legal education, legal information, legal advice and alternative dispute resolution as falling within the scope of the legal aid system, but only indirectly refers to them.

As indicated previously, the National Legal Aid Policy widens the scope of legal aid services for the provision of the full spectrum of legal services to the poor and vulnerable people. In 2019, the Ministry of Justice engaged the process of amending the Legal Aid Act in order to, inter alia, broaden the definition of legal aid in line with the National Legal Aid Policy. This will enable the Legal Aid Board and other legal aid service providers to apply more resources on legal education and awareness campaigns on the law and legal aid services amongst the population to empower people to claim their rights and obtain remedies.

5.2.3. Scope of the legal aid system

In terms of scope, the Legal Aid Act provides for legal aid in both criminal and civil matters (including administrative matters). In practice, the Legal Aid Board used to largely focus on criminal cases in the higher courts (High Court, Court of Appeal, Supreme Court).

However, in 2013, the Legal Aid Board developed an innovative scheme to expand the delivery of legal aid at Subordinate Court level, namely the Legal Services Unit. It takes the form of a permanent unit based and operating from the court premises, with daily outreach to remandees appearing in court and other parties in criminal and civil cases, providing them with the whole range of legal aid services, ranging from legal education and information to legal advice, mediation, legal assistance and representation in court. It is run jointly by paralegals affiliated to civil society organisations (namely Prisons Care & Counselling Association-PRISCCA, the National Legal Aid Clinic for Women-NLACW, Legal Resources Foundation-LRF and Prisoners Future Foundation-PFF) and legal aid assistants attached to the Legal Aid Board, all of them operating under the supervision of a Legal Aid Board legal practitioner. All Legal Services Unit staff have complementary profiles, roles and responsibilities. They operate according to quality standards set by the Legal Aid Board. The supervising legal practitioner from the Legal Aid Board ensures that professional standards are fully complied with. To date, the Legal Aid Board manages six Legal Services Units spread across three provinces in the country, operating at Subordinate Court level. In future, it is envisaged under the National Legal Aid Policy that Legal Services Units be also set up at high court level. In 2018, the six Legal Services Units based at Subordinate Court level provided legal aid to over 5,200 indigent and vulnerable parties in criminal (52%) and civil cases (48%). Women and juveniles constituted 33% of the clients. In 2017, the legal aid coverage in criminal matters at the Lusaka Subordinate Court was 24% (with the LSU Lusaka providing legal aid services in 850 criminal cases against 3,552 new criminal cases received by the Lusaka Subordinate Court in 2017).[3] In addition, all Legal Services Units organise regular outreach activities in communities and through local radios for awareness raising on the rights of suspects and accused persons, criminal offences, selected civil law topics, specific procedures in the criminal and civil justice system, and how to access legal aid services.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

5.3.1. Institutional and organisational description of the Legal Aid Board

As earlier stated, the Legal Aid Board is the statutory body with the mandate to provide and administer the legal aid system, with its mandate being expanded under the National Legal Aid Policy to include the coordination, regulation and monitoring of the legal aid system. The Legal Aid Board also advises the Minister of Justice on policies relating to the provision of legal aid and their implementation.

The Legal Aid Board is managed by a Director and Deputy Director assisted by a Secretariat, who operate under the supervision of a statutory Board consisting of a Chairperson and nine other Board members, appointed by the Minister of Justice. The Director is appointed by the Board (with the approval of the Minister of Justice). S/he is the Chief Executive Officer of the Legal Aid Board and responsible for the day to day operation and administration of the Legal Aid Board.

The Legal Aid Board is placed under the Ministry of Justice and reports annually to the Minister of Justice, with information on the activities and financial affairs of the Legal Aid Board. However, and as outlined in the National Legal Aid Policy, the Legal Aid Board is, in the performance of its functions, independent of the direction or control of any person or authority except as otherwise prescribed under the Legal Aid Act. It guarantees that Legal Aid Board decisions on the granting of legal aid are made objectively on the basis of need, and not influenced by any discriminatory bias. In practice, the Legal Aid Board has been representing clients taking legal action against the government and other public authorities.

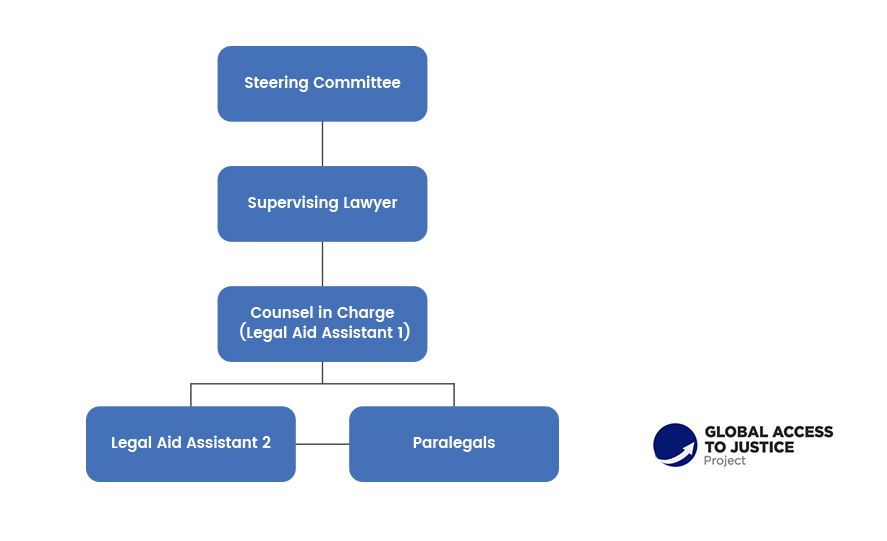

According to the Legal Aid Act, applications for legal aid are to be made to the Director of the Legal Aid Board. In practice, the Director designates a Counsel in Charge at each Legal Aid Board Office to apply provisions on the granting of legal aid. Similarly, decisions on the management of cases being granted legal aid are placed under the authority of the Legal Aid Board and not under the control of the Ministry of Justice.

In terms of financial resources, the Legal Aid Board manages its own budget which includes both the Legal Aid Fund and the general budget of the Legal Aid Board (see further details below in 5.4. Legal aid budget).

The Legal Aid Board has a total of 12 offices country wide, reaching out to all provinces in Zambia with one Legal Aid Board provincial office per province, and two Legal Aid Board district offices, one in Copperbelt province and another one in Southern province. The Legal Aid Board provides services at all courts of law in Zambia in both criminal and civil cases. However, as mentioned earlier, over the last years the focus has largely been on criminal cases in the higher courts (High Court, Court of Appeal, Supreme Court). This is due to serious constraints at the Legal Aid Board with regards to capacity in terms of human and financial resources. As at April 2019, the Legal Aid Board had 31 legal practitioners (in full-time employment for the Legal Aid Board) and 23 legal aid assistants (that are law graduates who are in the process of completing professional education at the Zambia Institute of Advanced Legal Education (ZIALE), attached to the Legal Aid Board and granted limited right of audience as per the provisions of the Legal Aid Act) as members of staff (against current approved establishment of 86 in the Legal Aid Board), against the population of more than 17 million. This makes a ratio of 1 Legal Aid Board lawyer (including Legal Aid Board legal practitioners and legal aid assistants) to 314,815 persons. Some provinces only have one Legal Aid Board legal practitioner for the whole province covering over 1,000,000 persons. In addition to legal practitioners and legal aid assistants, the Legal Aid Board has 74 support staff providing administrative and operational support.

In 2018, the Legal Aid Board received 12,071 applications for legal aid out of which 6,397 were granted legal aid (in the form of legal assistance and representation), of which 70% criminal cases, while the other 5,674 applicants were provided with legal information and advice only. In civil cases, the Legal Aid Board may also provide mediation services.

As earlier stated, in 2013, the Legal Aid Board developed an innovative scheme to expand the delivery of legal aid in criminal and civil cases at Subordinate Court level, namely the Legal Services Unit. To date, the Legal Aid Board manages six Legal Services Units spread across three provinces in the country.

In addition, the Legal Aid Board provides supervision to a network of ten legal desks based in correctional facilities and police stations. In 2018, these ten desks operated by paralegals affiliated to civil society organisations (namely Legal Resources Foundation-LRF, Prisoners Future Foundation-PFF, Undikumbukire Project Zambia-UP Zambia and Caritas Monze) provided legal aid (in the form of legal advice, mediation where applicable, and legal assistance) to over 5,100 persons in detention. They further organise legal education sessions targeting inmates and persons in police custody.

Where necessary and for specific cases, the Legal Aid Board engages legal practitioners in private practice under the Judicare system to take up cases at prescribed fees.

In 2012, the Access to Justice Situation Analysis study identified that the various legal aid providers were perceived by justice sector stakeholders as the least corrupt justice agency in their areas.[4]

5.3.2. Mixed legal aid delivery system

As outlined above, the National Legal Aid Policy establishes a mixed legal aid delivery system involving complementary legal aid service delivery models based on cooperation and engagement between state and non-state legal aid service providers.

In that regard, legal aid service delivery models include:

- The Legal Aid Board offices (see above 5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid, Institutional and organisational description of the Legal Aid Board);

- Legal Services Units at court level (see above 5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid);

- Correctional facility and police station legal desks (see above 5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid, Institutional and organisational description of the Legal Aid Board);

- Civil society organisation legal desks;

- The Judicare system;

- The pro bono legal aid scheme; and

- University law clinics.

Over 30 civil society organisations are engaged in legal aid with paralegals providing legal aid services at community level with a focus on vulnerable groups and/or rural areas, and at varying levels of the justice system in Zambia. However, the number of civil society organisations providing legal aid services is limited and there are no permanent university law clinics in existence (though a number of public and private universities are taking concrete steps towards establishing such university law clinics). The number of active paralegals is in the range of 500 countrywide.

As indicated previously, the National Legal Aid Policy officially recognises civil society organisations and university law clinics as legal aid service providers, subject to their accreditation at the Legal Aid Board. The accreditation process will be based on rules and procedures issued by the Board of the Legal Aid Board, with accreditation certificates issued by the Secretariat of the Legal Aid Board.

The National Legal Aid Policy also creates a framework for non-legal practitioners to deliver legal aid services in Zambia. This includes paralegals and legal assistants (law degree holders) with a requirement that they register at the Legal Aid Board for purposes of providing legal aid.

Paralegals are organised in three levels whereby qualification requirements match the various levels of specialisation. In July 2018, the Technical Education, Vocation and Entrepreneurship Training Authority (TEVETA) approved the newly established three-level training scheme for paralegals in Zambia, in line with the National Legal Aid Policy. For all the three levels of the training scheme, the training curriculum includes a specific focus on practice skills required by paralegals to effectively and efficiently provide legal aid services. Reference training manuals for paralegals were developed for all the three levels by Caritas Zambia for level 3, Cavendish University for level 2 and the Zambia Institute of Advanced Legal Education-ZIALE for level 1.

The three levels of paralegals are organised as follows:

- Paralegals level 3 at skills award level based on a 130 hours training course;

- Paralegals level 2 at trade test level based on a 780 hours training course;

- Paralegals level 1 at certificate level based on a 1,620 hours training course and an attachment for a duration of 780 hours.

In 2019, different university, higher educational institution and civil society organisations (namely ZIALE, Cavendish University, Caritas Zambia, PAN, NLACW, Prisoners Future Foundation-PFF in partnership with Mulungushi University, Young Women Christian Association Kitwe-YWCA Kitwe, and Women and Law in Southern Africa-WLSA) accredited as training providers with TEVETA. With support from the PLEED Programme, they organised training courses at all three levels of the newly adopted paralegal training scheme, training a total of 255 paralegals in 2019 (with 89% pass rate).

The quality assurance framework for paralegals will be further developed by a multi stakeholder Paralegal Standing Committee to be constituted by the Legal Aid Board. This will ensure the competence and accountability of paralegals in the legal aid services delivered.

With regard to the legal profession, the National Legal Aid Policy promotes the establishment of a comprehensive pro bono framework for an increased number of legal practitioners to provide legal aid services on a pro bono basis. This will ensure legal practitioners take on pro bono cases and complement legal aid work carried out by the Legal Aid Board, civil society organisations and university law clinics.

5.3.3. Development strategy of the legal aid system

The reason for developing the National Legal Aid Policy was to provide a comprehensive national strategy on legal aid and a corresponding implementation framework to guide the provision of legal aid services by all legal aid service providers, including non-state actors, and remedy the gaps identified in the provision of legal aid. These included the limitations in the definition of legal aid in the Legal Aid Act, the limited legal awareness amongst the population, the insufficient geographic coverage of the legal aid system, the limited role of the legal profession in the delivery of legal aid services, the unregulated provision of legal aid services provided by paralegals and law degree holders (legal assistants), and the limited institutional capacity in operating a comprehensive legal aid system.

The National Legal Aid Policy aims at installing a comprehensive legal aid system that is accessible, effective, credible and sustainable. On this basis, the National Legal Aid Policy establishes a renewed regulatory and implementation framework for the provision, administration, coordination, regulation and monitoring of legal aid in Zambia.

In order to support increased engagement and participation from civil society organisations in the governance of the legal aid system, the National Legal Aid Policy provides for a representative from a civil society organisation providing legal aid to be a member of the Board of the Legal Aid Board, in light of the essential role played by civil society organisations and their affiliated paralegals in the delivery of legal aid services.

Similarly, the National Legal Aid Policy provides for a multi stakeholder Paralegal Standing Committee which should include paralegals, civil society organisations, legal practitioners, representatives from the Legal Aid Board and other relevant institutions as constituted by the Legal Aid Board. Functions of the Paralegal Standing Committee would include the further development of the quality assurance framework for paralegals (including registration requirements, training scheme, quality standards and professional ethics, and disciplinary process), the review of applications submitted by paralegals level 3, 2 and 1 for registration at the Legal Aid Board, and other functions as may be assigned to the Committee by the Legal Aid Board.

5.4. Legal aid budget

The sources of legal aid funding for the Legal Aid Board include:

- Monies from the state budget appropriated by Parliament for the purposes of operations of the Legal Aid Board;

- Grants or donations;

- Monies generated by the Legal Aid Board in the course of its activities. These include:

- Consultation fees paid by legal aid applicants;

- Contribution fees paid by legally aided persons;

- Costs awarded to legally aided persons.

The National Legal Aid Policy provides for additional sources of funding for the Legal Aid Board, with:

- Bequests;

- Deductions from awards to legally aided persons;

- Licensing fees, which will include fees paid to the Legal Aid Board by civil society organisations and university law clinics for their accreditation, and by legal assistants and paralegals for their registration, once the Legal Aid Act is amended in line with the National Legal Aid Policy, and the accreditation/registration scheme is operational.

The state funding allocated to legal aid is placed under the Ministry of Justice, with a specific sub budget line for the Legal Aid Board, and another one for the Legal Aid Fund administered and managed by the Legal Aid Board.

In terms of process, the Legal Aid Board prepares its budget and present it to the Ministry of Justice. The Legal Aid Board then defends its budget during a budget meeting with Ministry of Justice officials, where the proposed budget will be discussed and refined depending on resources available.

The funding of the Legal Aid Board in the 2019 State Budget is as follows:

| 2019 Legal Aid Board (LAB) Budget | Increase (in Zambian Kwacha, from 2017 Budget) | |

| LAB General Budget (including operational costs) | 19,460,500 ZMW

equiv. to 1,332,911 USD[5]

|

+5% |

| LAB Legal Aid Fund (covering additional costs related to the provision of legal representation) | 2,589,450 ZMW

equiv. to 177,360 USD |

+5% |

| Total | 22,049,950 ZMW

equiv. to 1,510,271 USD |

+5% |

This level of state funding translates to 0.09 USD per person on legal aid in Zambia in 2019.

The Legal Aid Board receives additional financial and technical support under the PLEED Programme, aimed at improving the institutional and organisational capacity of the Legal Aid Board in delivering legal aid. The PLEED Programme also supports the operation of a network of 6 Legal Services Units at Subordinate Court level managed by the Legal Aid Board, and further supervision by the Legal Aid Board of the 9 legal desks based in correctional facilities and police stations and operated by civil society organisations (see above 5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid).

5.5. Legal aid providers

The legal staff of the Legal Aid Board includes:

- Legal practitioners that are qualified practitioners under the Legal Practitioners Act, and employed by the Legal Aid Board on a full-time and salaried basis; and

- Legal aid assistants that are law graduates who are in the process of completing professional education at the Zambia Institute of Advanced Legal Education (ZIALE), attached to the Legal Aid Board and granted limited right of audience as per the provisions of the Legal Aid Act. The Legal Aid Board has two remuneration schemes for legal aid assistants, some receiving an allowance, while others become salaried members of staff.

Legal aid assistants are primarily young lawyers willing to practice while completing their professional education at ZIALE. Joining the Legal Aid Board constitutes a unique learning opportunity as they will be able to provide legal representation at Subordinate Court level (and in chambers at the High Court), despite not being fully qualified legal practitioners, therefore acquiring a lot of experience.

Conditions of services at the Legal Aid Board have improved over the last years, allowing the Legal Aid Board to retain its staff for longer periods of time. This includes legal aid counsel (legal practitioners employed by the Legal Aid Board) whose remuneration is now equivalent to State Advocates from the National Prosecutions Authority. Remuneration of legal aid counsel is also competitive when compared to the salary or fees earned by private lawyers in the regular market when starting their practice.

The procedure to become a legal aid counsel or legal aid assistant at the Legal Aid Board involves the following steps: a recruitment notice is advertised, and a Legal Aid Board committee reviews and shortlists the applications received. Shortlisted candidates are interviewed and assessed by a panel at the Legal Aid Board. The assessment looks at the performance of the candidate based on a series of questions, including practical questions on procedural issues.

The National Legal Aid Policy provides that the Legal Aid Board will also be able to employ paralegals, in addition to legal practitioners and legal aid assistants.

Legal practitioners that are willing to provide legal aid under the Judicare system must be registered at the Law Association of Zambia, hold a valid practice certificate, and apply to the Director of the Legal Aid Board to be registered under the Judicare system. When registering them, the Legal Aid Board ensures that interested legal practitioners have sufficient experience to handle cases.

Legal practitioners under the Judicare system receive a fixed fee set at 4,000 ZMW (equivalent to 274 USD) for each case handled. In addition, the Legal Aid Board will cover such expenses incurred by the legal practitioner while representing a legally aided person under the Judicare system, which are properly attributable to the time spent or work done by the legal practitioner in representing the person.

As outlined in the National Legal Aid Policy, the Legal Aid Board is, in the performance of its functions, independent of the direction or control of any person or authority except as otherwise prescribed under the Legal Aid Act. It guarantees that Legal Aid Board decisions on the granting of legal aid are made objectively on the basis of need, and not influenced by any discriminatory bias. According to the Legal Aid Act, applications for legal aid are to be made to the Director of the Legal Aid Board. In practice, the Director designates a Counsel in Charge at each Legal Aid Board Office to apply provisions on the granting of legal aid. Similarly, decisions on the management of cases being granted legal aid are placed under the authority of the Legal Aid Board and not under the control of the Ministry of Justice or other government institutions.

However, the Legal Aid Board and other legal aid providers do not have functional or procedural special prerogative or privilege to facilitate their professional performance.

5.6. Quality assurance