National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

1.1. Form of government

Turkey is a republic and has a unitary structure. Under Article 6 of the Constitution, sovereignty as the only and unconditional source of power, belongs to the nation. Article 2 of the 1982 constitution sets out the characteristics of the Republic as democratic, secular and social state, governed by rule of law, within the notions of public peace, national solidarity and justice, respecting human rights, loyal to the nationalism of Atatürk, and based on the fundamental tenets set forth in the preamble.[1]

Turkey recently switched from a parliamentary to a presidential system of governance after a referendum on April 16, 2017 that was approved by 52% of the electorate. The constitutional package was introduced along with other amendments[2] and has been put into effect with presidential and parliamentary elections taking place on June 24, 2018.[3] This change in the system[4] granted the President extended set of powers including the ability to renew the elections, to appoint vice presidents and ministers, senior government officials and members of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors (Hakimler Savcılar Kurulu – HSK).[5] This new system is not a replica of a standard presidential system as strict separation of powers – trademark of a typical presidential system – is absent and regular checks and balances are avoided, leaving the President with unconditional powers.

1.2. Demographics, ethnic groups, languages and religion

According to Turkish Statistical Institute (Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu – TUİK), as of December 31, 2018, Turkey’s population is 82,003,882, 92.3% of which live in urban centers, while only 7.7% lives in rural centers and villages.[6]

In Turkey, official data on ethnic identity has not been collected since 1985[7]. Reportedly, the reason why such inquiry was removed from these polls was the potential threat it posed for the indivisibility of the state and its nation, one of the pillars of official discourse.[8] In addition, in Turkey “minorities” has historically been a politically “sensitive” issue that is discussed only at the legal level, and not as a sociological reality.[9] According to the legal definition, as outlined by 1923 Lausanne Treaty[10], only non-Muslim groups (Greeks, Armenians and Jews) are recognized as minorities. Hence, any attempt from other groups – particularly Kurds – to claim a minority status has been interpreted as a hostile act against the unity of the state with its nation.[11]

Nevertheless, in 2011 a nation-wide survey on the Kurdish issue was conducted by an independent research group.[12] The survey was based on 2010 data and it revealed the following distribution of ethnic groups based on self-identification:[13]

- 7% Turkish

- 5% Kurdish

- 2% Zaza

- 2% Arab

- 4% Other (including – non-Muslim, Roma, Balkan, Caucasian etc.)

Turkish is the only official language of the State. The State does not have an official religion since 1928, when the clause defining Islam as the religion of the State was removed from the 1924 Constitution. Turkey, however, has a predominantly Sunni Muslim population. A recent research by KONDA revealed that in Turkey in the last ten years (2008-2018), the percentage of people who call themselves “religious” has decreased from 55% to 51%, with the number of people who say they are “devout” decreased from 13% to 10%. Non-believers, however, seem to be on the rise. In the last decade, the number of people who call themselves “atheist”, although still quite small, has tripled from 1% to 3%, while the number of those who say they are “non-believer” has increased from 1% to 2%.[14]

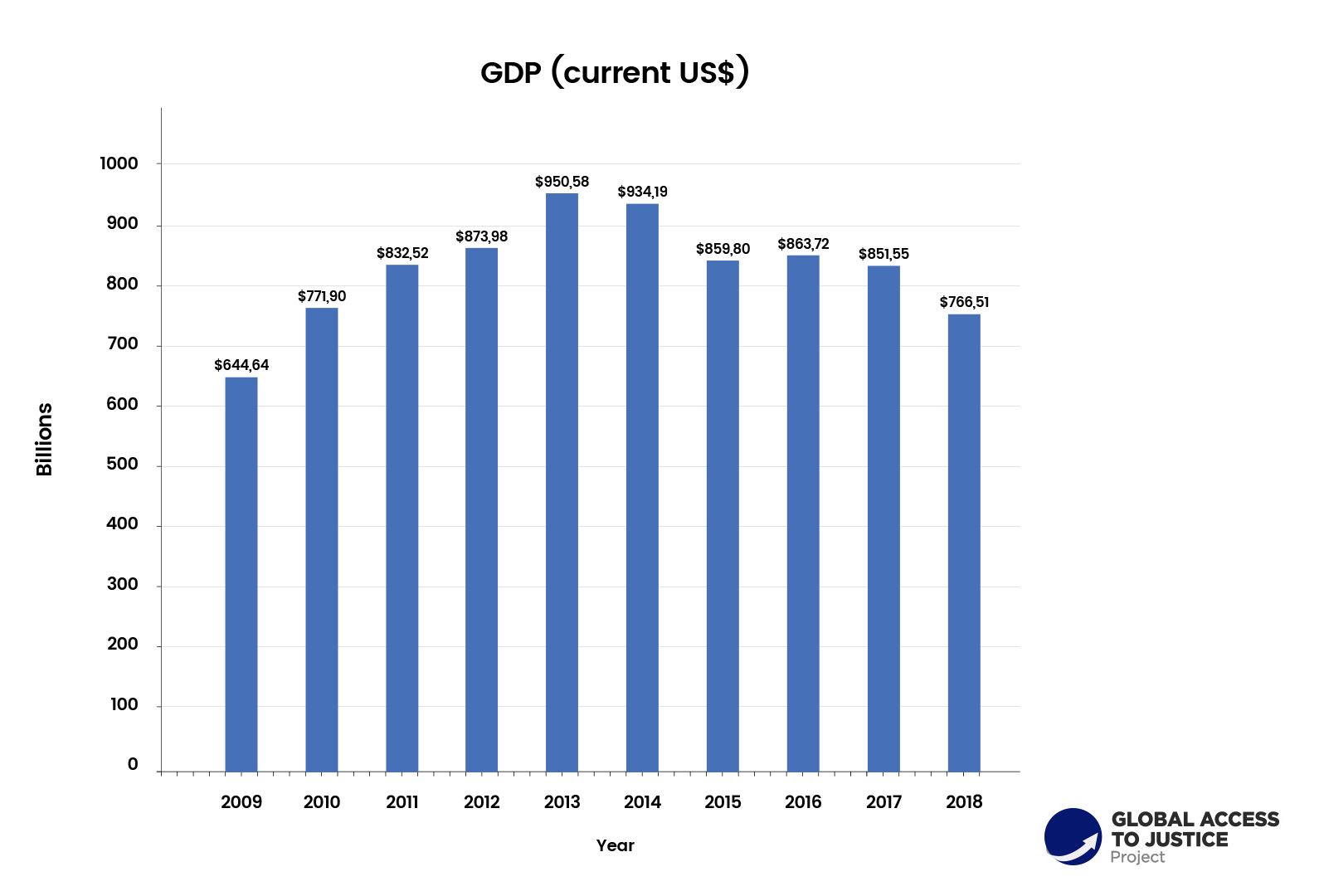

The gross domestic product (GDP) and the gross national income purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP) for the period of 2009-2018 are shown in the following charts.

Chart 1. GDP (2009-2018)

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/country/turkey

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/country/turkey

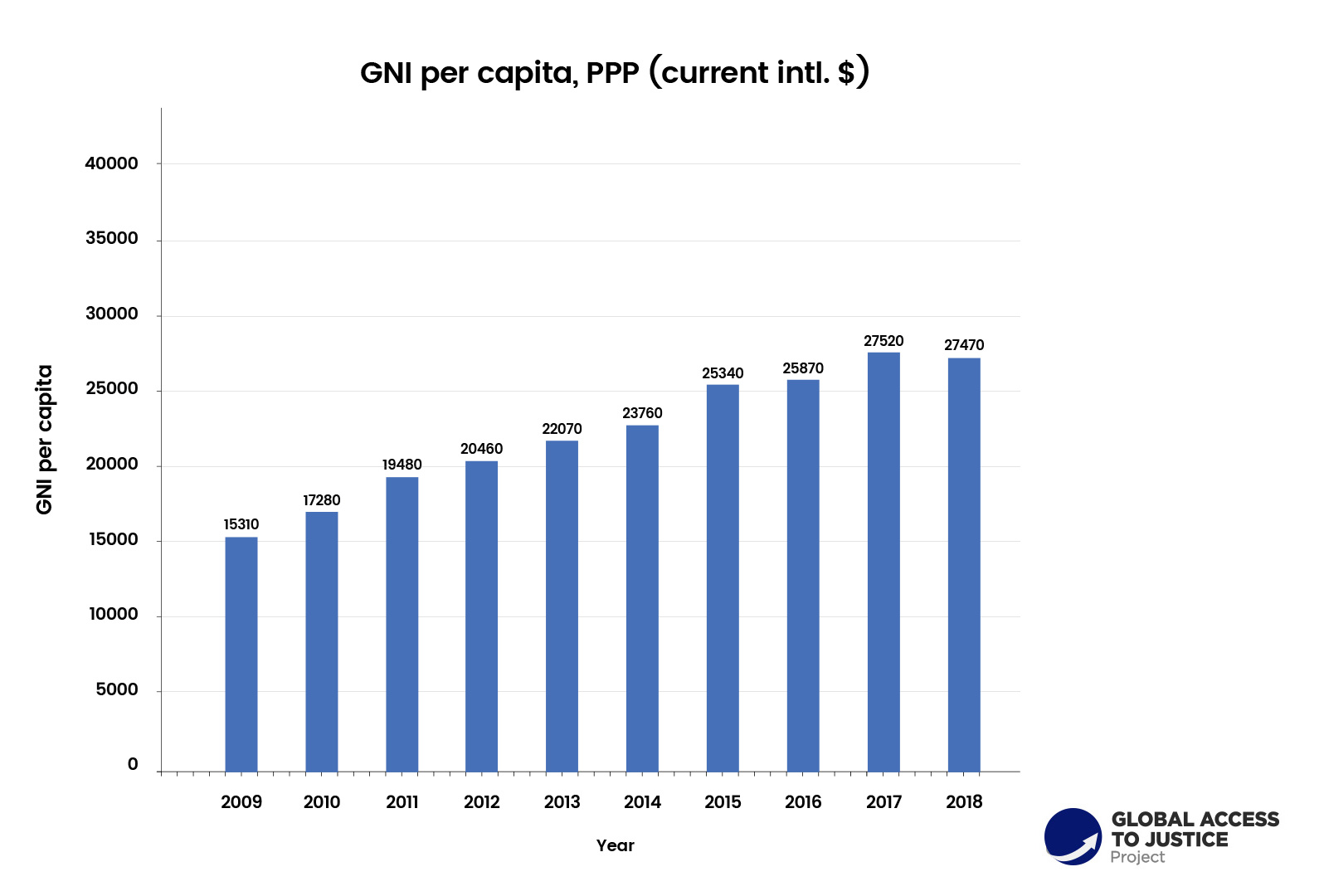

Chart 2. GNI (PPP) (2009-2018)

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/country/turkey

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/country/turkey

In 2016, data from TUİK showed that poverty line (basic food + nonfood; below 60% of GDP per capita) for a family of four was 8,539 TL with 21.2% of population living below poverty line. Absolute poverty line (food) was set at 2,15 USD daily with 0.06% of population living below the line.

The most updated national data on these indicators, however, are provided by TÜRK-İŞ (Türkiye İşçi Sendikaları Konfederasyonu – Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions). TÜRK-İŞ has been collecting data on the livelihood of the working population on a monthly basis. May 2020 results from TÜRK-İŞ are as follows:[15]

- Poverty line for a family of four (monthly) – 7,942 TL (app. 1170 USD)[16]

- Absolute poverty line for a family of four – 2,438 TL (app. 360 USD)

The World Bank reports that although poverty rate in Turkey declined significantly from 27.3% to 9.9% from 2004 to 2006, since 2018 unemployment and inflation have been rising steadily.[17] In 2020, the minimum wage has been set as 2,324 TL (app. 341 USD)[18] after taxes.

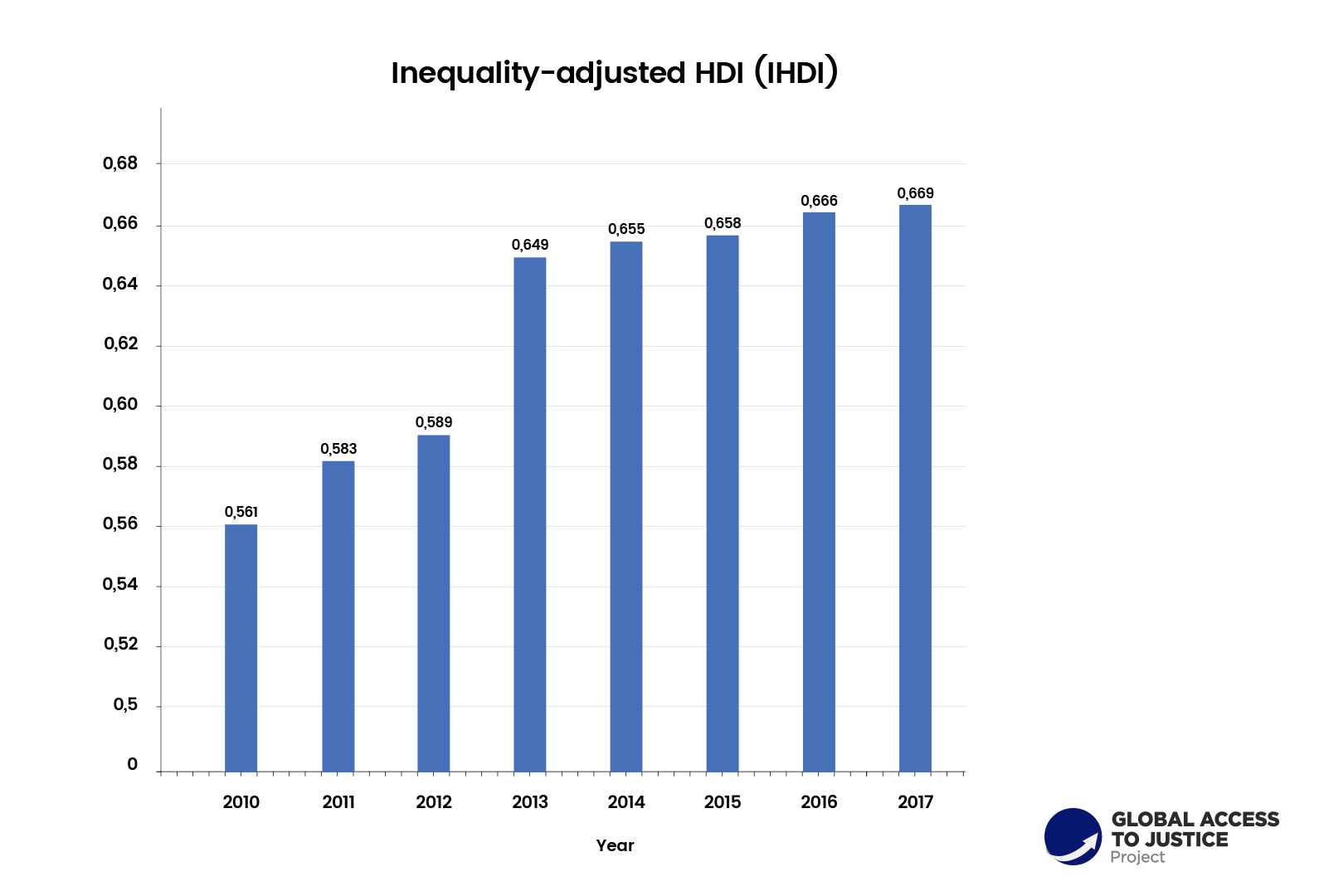

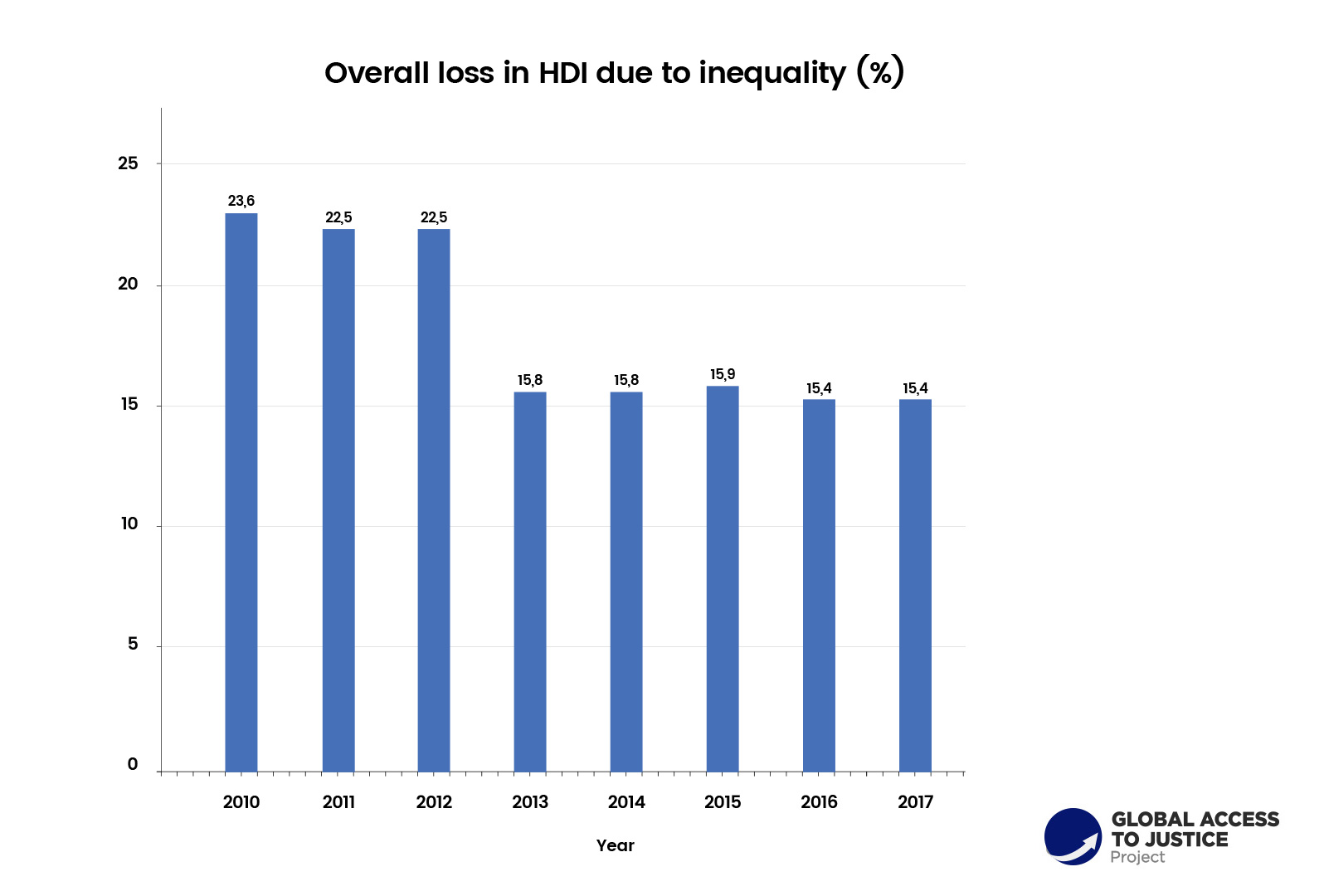

For inequality index and poverty line, please see the following charts.

Chart 3. Inequality – adjusted HDI (2010-2017)

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/138806

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/138806

Chart 4. Loss in HDI (2010-2017)

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/73506

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/73506

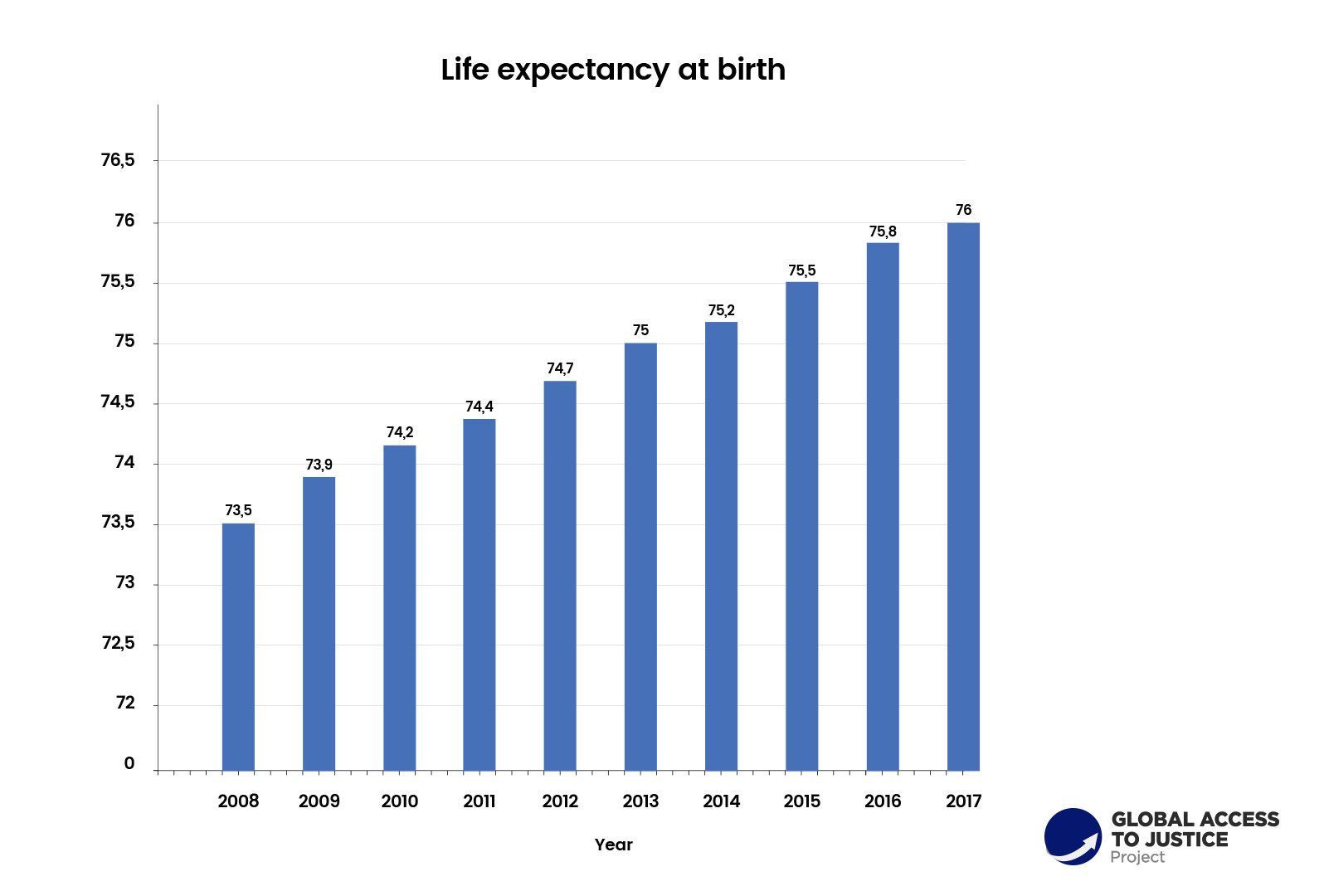

Chart 5. Changes in life expectancy at birth (2008-2017)

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/69206#

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/69206#

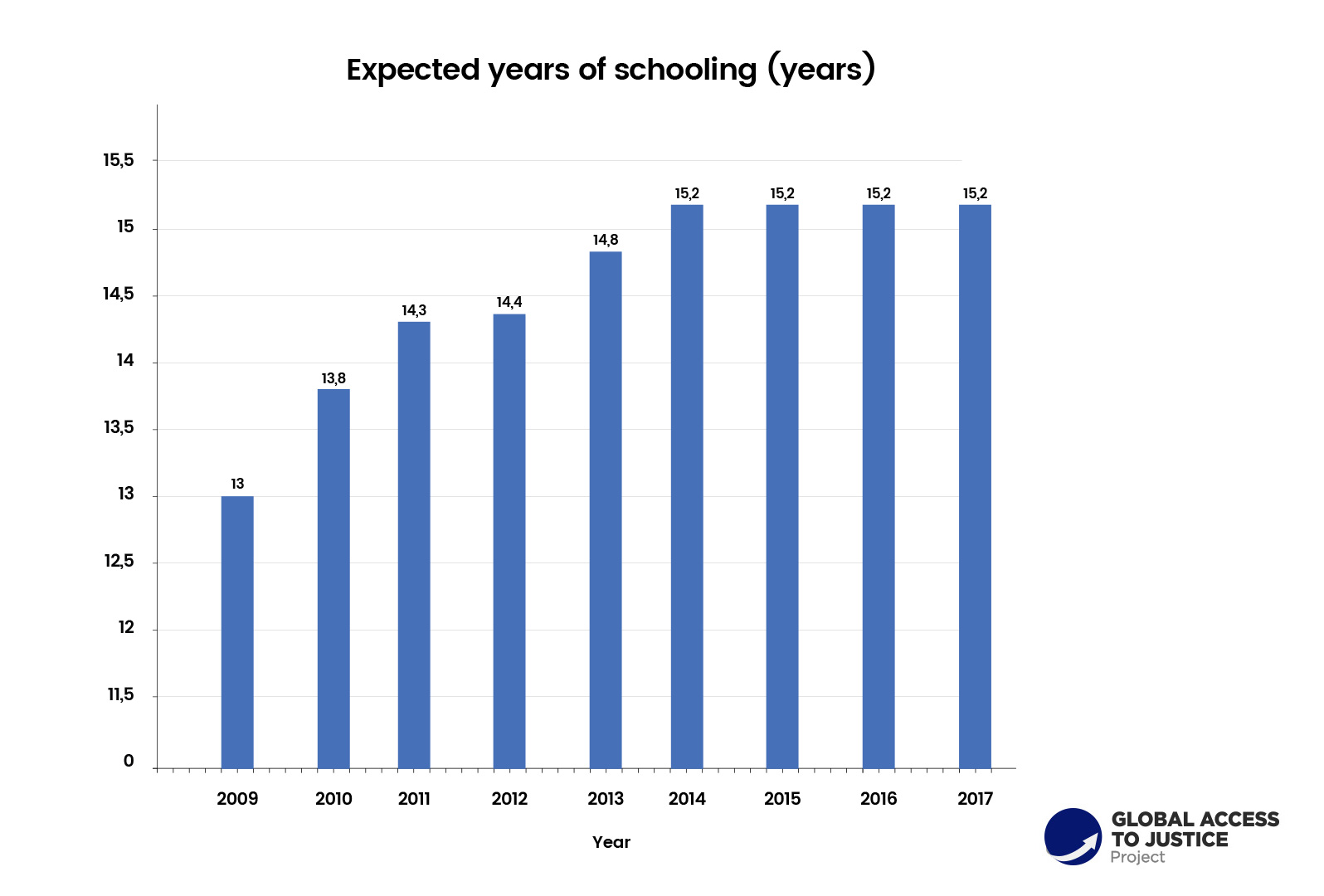

Chart 6. Expected years of schooling (2009-2017)

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/69706

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/69706

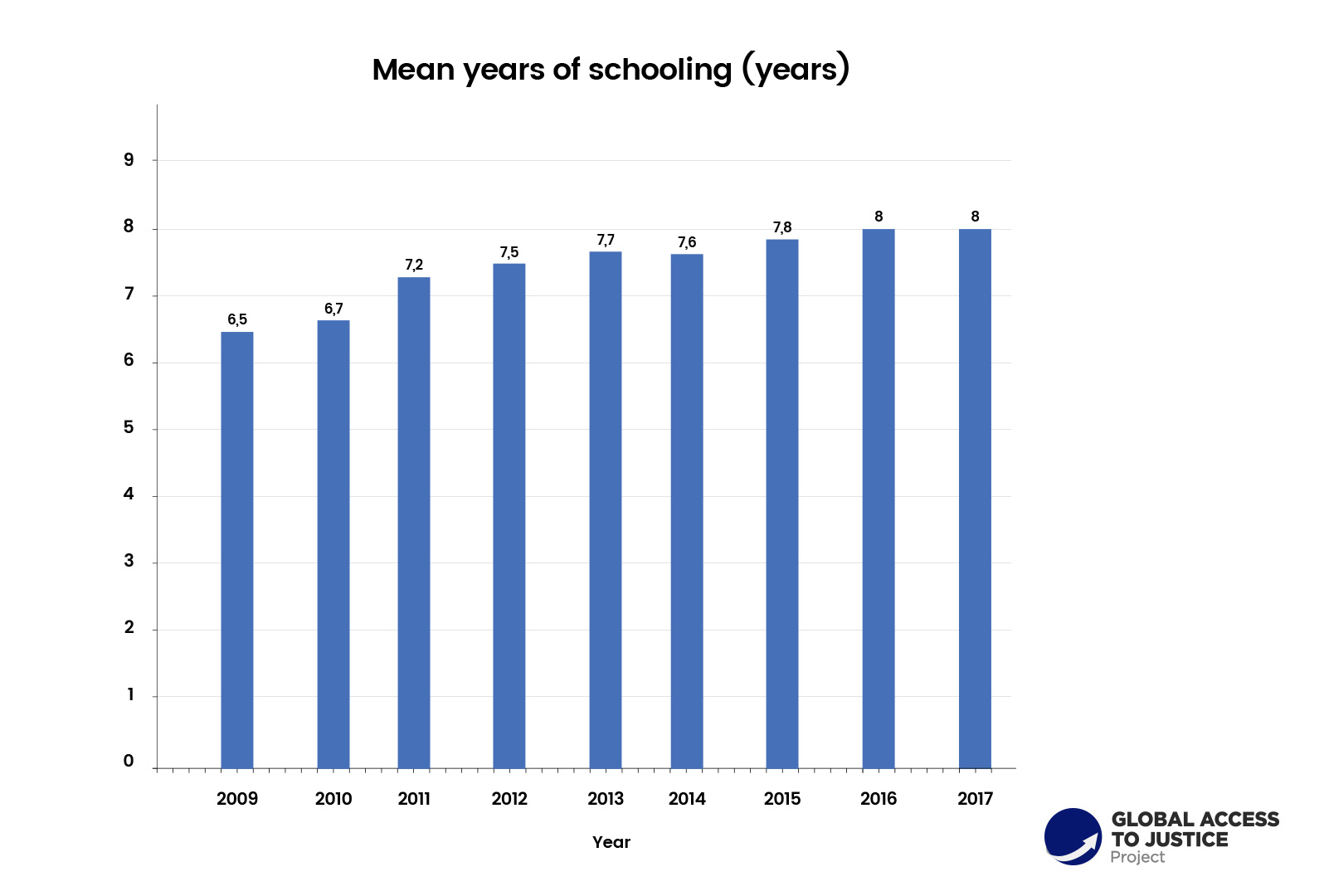

Chart 7. Mean years of schooling (2009-2017)

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/103006

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/103006

Turkey’s HDI (Human Development Index) value for 2017 is 0.791 which places her in the high human development category at 64th position out of a total of 189 countries.

Chart 8. Human Development Index

| Human Development Index | Index | Rank |

| 0.791 | 64 |

Between 1990 and 2017, Turkey’s HDI value increased from 0.579 to 0.791, an increase of 36.6%. Chart 9 shows Turkey’s progress in each HDI indicator: life expectancy, mean years of schooling, expected years of schooling and GNI per capita.

Chart 9. Progress in different HDI indicators (1990-2017)

| Life expectancy at birth | Expected years of schooling | Mean years of schooling | GNI per capita (2011 PPP$) | HDI value | |

| 1990 | 64.3 | 8.9 | 4.5 | 11,214 | 0.579 |

| 1995 | 67.0 | 9.6 | 4.8 | 12,089 | 0.607 |

| 2000 | 70.0 | 11.1 | 5.5 | 13,656 | 0.655 |

| 2005 | 72.5 | 11.9 | 6.0 | 16,129 | 0.690 |

| 2010 | 74.2 | 13.8 | 6.7 | 17,804 | 0.734 |

| 2015 | 75.5 | 15.2 | 7.8 | 23,125 | 0.783 |

| 2016 | 75.8 | 15.2 | 8.0 | 23,500 | 0.787 |

| 2017 | 76.0 | 15.2 | 8.0 | 24,804 | 0.791 |

Source: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/TUR.pdf

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of legal system

Turkey is a member of the civil law family prevalent in Continental Europe. The bifurcation between religious law and the civil law of the late Ottoman era has been abandoned with the proclamation of the Republic in 1923.

2.2. Organization of the justice system

The justice system is unitary with multiple levels of courts. At the lowest level, there are the courts of first instance. There are fifteen courts of intermediate appeal that are organized at the regional level. Finally, at the highest level is the Court of Cassation or Appeal in Ankara. In addition, there is a Constitutional Court that hears constitutionality issues brought either by courts or by citizens. It also hears individual applications before they are submitted to the European Court of Human Rights.

The number of cases handled by courts of first instance keeps growing. According to the 2018 data, the total number of civil cases filed in Turkey was 2,107,855 while the total number of decided cases was 2,067,422.[1] The judicial statistics only provide the number of cases filed per city, not per court, and this can vary greatly. For instance, the number of cases filed in Istanbul as the largest city of Turkey was 415,649 while in Bayburt, one of the country’s least populated cities, the same number was 1,314.[2]

There are no parallel-informal justice structures.

2.3. The structure of the legal profession

In terms of the legal profession, the main division is not on the basis of the premise of representation such as barrister and solicitor, but between functions performed on the bench and otherwise. In other words, being also civil servants, judges and prosecutors (of the Republic) are treated as a separate group than attorneys. Judges and prosecutors are regulated by the same law[3] and are subject to similar status. Most of them enter the profession at a young age, often without lengthy years of professional practice as an attorney. Their professional education conditions them to socialize with each other despite performing different functions. Prosecutors’ close social relationship with judges starts when they are candidate judges and prosecutors during their internship and continues throughout their career. They are professionally regulated by the same law, they reside in the same buildings (provided by the State), commute to work together (in shuttles provided by the State), usually vacation in the same place, marry each other and work in the same building next to each other. Not surprisingly, this leads attorneys to feel sidelined.

The Code on Attorneys dates from 1969 despite the fact that the profession changed very much since then.[4] The last serious amendments in the law took place in 2001. Attorneys still cannot establish corporations themselves let alone ones that can be managed by non-lawyers. As of December 31, 2019, the Union of Turkish Bar Associations (Türkiye Barolar Birliği – TBB) gives the number of attorneys in Turkey as 127,691.[5] This does not include the number of judges and prosecutors.

2.3.1. Number of licensed practicing lawyers

The number of attorneys in Turkey grew exponentially since 1990s with the opening up of growing number of law schools. Today, there are more than a hundred law schools in the country with similar curricula but serious differences in the quality of education. Competition in the profession has become fierce, lowering the ethical standards in the profession and often leading to the “proletarianization” of especially young lawyers who usually work on wage and are alienated to their labor.[6] Often there have been calls for a halt to the expansion of law schools. Equally, an attempt was made to introduce a bar exam. However, due to an inflammatory speech of the President of the Union of Turkish Bar Associations that personally attacked the then Prime Minister Erdoğan, the exam requirement was lifted.[7] The relationship between the profession and the government, historically always problematical, did not recover ever since.[8]

2.3.2. Affordability of legal fees

The fees charged by practicing attorneys is not affordable for the general population. A 2007 nationwide study on the opinions of the public on courts and the judicial system found that only 18% of the urban population ever used the services of an attorney, with men (24.3%) being twice likely to do so than women (12.8%).[9] The three most common reasons for not going to an attorney were that the people thought they could defend themselves, that the services were expensive and that attorney services caused delays. These answers suggest that not only the services are expensive, but the public does not understand or appreciate the nature of the work done by attorneys, an outcome that should not be surprising given that there is still a blanket prohibition of attorney advertisement.

2.3.3. Legal representation in Court

Representation by an attorney is not mandatory in the justice system at least for real persons although the abovementioned survey also found out that 54.3% of the urban population believed (mistakenly) this to be the case. There have been often calls for the introduction of a mandatory insurance system, designed after the German model. There are also no paralegals in the Turkish system.

2.3.4. Judicial Careers

On a textual level, at least in terms of constitutional wording, the usual guarantees of judicial independence can be observed. However, on a practical level, and given the authoritarian turn in the country, it is no longer possible to say that there is judicial independence in Turkey, especially in politically sensitive cases.

Judges are recruited by the executive power in a nontransparent fashion. Once they pass a written exam, they are subject to an interview, conducted by a commission under the influence of the Ministry of Justice.[10] Upon the completion of their apprenticeship, they are then appointed to their first post by the Council of Judges and Prosecutors.

As of September 3, 2019, the Council of Judges and Prosecutors gives the total number of judges as 14,131, 54% of which are male and 46% are female.[11] As there is no ethnicity or race based data collected by the government, it is not possible to say the percentage of representation by ethnicity.

The compulsory retirement age for judges is 65. There is no geographical immunity for judges in Turkey. In fact, the country is divided into regions according to various development indicators.[12] Judges are expected to serve in various parts of the country for a pre-determined period of time. In other words, they cannot decide where they will be working. The Council of Judges and Prosecutors rotates them during their service. Other than serving their pre-determined time in a region, judges may be transferred for organizational and disciplinary reasons. There are not many safeguards in place against abuse of this authority. In fact, with the authoritarian turn in Turkey, and the takeover of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors by the government, many judges whose decisions were not liked, were rotated many times within short periods of time, some of whom preferred retiring as soon as they were entitled to, instead of putting up with this organizational harassment. When one remembers how the members of the Council are appointed (either by the Head of State or institutions under his control), judges and prosecutors have no working recourse against the Council’s decisions.

2.3.5. Prosecutorial Careers

Prosecutors are subject to the authority and instructions of the Head Prosecutor in every city. All their investigations are conducted on behalf of the Head Prosecutor. The status of the prosecutors of the Republic is therefore more of an executive one as they are also not provided with independence. Despite all this, they are regulated by the same legislation as judges[13]. Therefore, all the above explanations with regards to selection, appointment and rotation also apply to them. The total number of prosecutors is 6588 of which only 14% are women as prosecution is still seen as a man’s job.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

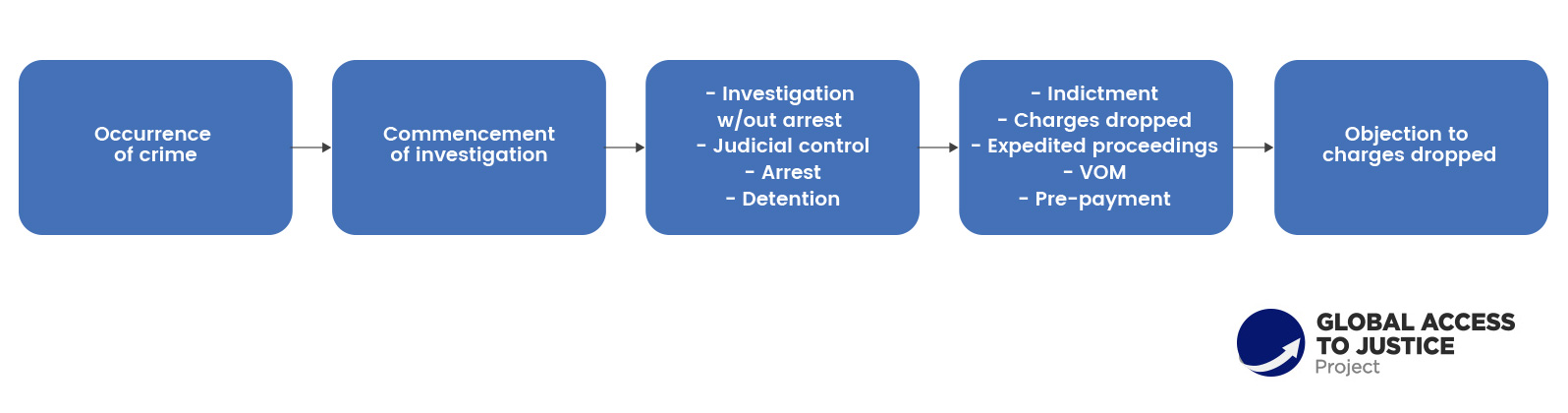

3.1. Criminal Procedure

3.1.1. Criminal investigations

The prosecutor is the head of the investigation process[01]. When performing judicial functions, the police (as well as the Gendarmerie[02] , Customs Control and Coast Guard and other public authorities) are to follow the order and instructions of the prosecutor. Criminal proceedings may be initiated following the complaint of the person who has been the victim of a crime, or who has been affected by the crime (for example, if the victim is dead his/her family), or ex officio by the prosecutor. Some crime investigations can only be initiated if there is a complaint by the victim while some are subject to permission and request. Nevertheless, if the victim chooses to first go to the police, the police shall inform the prosecutor of the occurrence of the crime. Similarly, complaints made before other public authorities shall be sent to the prosecution for processing. If, however, the victim chooses to go to the prosecutor first, he/she directs the inquiry to the respective division of the police, be it narcotics, murder or otherwise.

While citizens make their complaints mostly by going to the police, the prosecutor does not have his/her own staff to undertake the investigation, but instead relies on the police. At the same time, the prosecutor only has limited control of the police, because there are no separate judicial police as an entity that works under the authority of the prosecutor. Nevertheless, when the police conduct an investigation, the prosecutor must get involved, since the police must act according to the instructions of the prosecutor. Indeed, the prosecutor asks the police to carry out various actions. For instance, the police are asked to take the statement (interview) of the victim, witness and the suspect, or obtain the final medical report.[03]

The police have apprehension powers without a warrant if the person is caught in flagrante delicti and, in addition, is considered likely to abscond, or his/her identity cannot be instantly determined. The police must inform the prosecutor when they detain a person who can then order the police to release him/her. A person who is not released within 24 hours must be brought before the judge for interrogation. This period may go up to 36 hours to allow time for travel. [04]The suspect can also be taken to the courthouse at the place of his/her apprehension or to the closest courthouse with the infrastructure of an online and visual communication system so that his/her statement can be obtained within 24 hours. If a warrant for apprehension is issued by a court, but the suspect is detained within the jurisdictional boundaries of another court, the latter may arrest him/her temporarily, prior to the suspect being sent to the court issuing the warrant. The detainee must be brought before the court within a maximum of 24 hours following the apprehension.[05]

In Turkey, crimes that involve more than three suspects have come to be treated in a separate category even if the suspects do not share a common criminal goal. Consequently, in these cases, the period can be extended by the order of the prosecutor up to three days, extended by one day each, at a time.[06]

In 2015, following the Gezi events, the police force was given apprehension powers to be exercised in flagrante delicti situations involving multiple suspects during social unrest. In addition, pursuant to Article 91/4 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP), for additional crimes such as homicide, physical assault, sexual assault, child molestation, theft, burglary, production and trade of illegal substances, terror crimes etc., the period of apprehension has been expanded to 48 hours which is twice the amount of what the prosecutor can determine in a crime involving an individual suspect. More worryingly, this period can go up to four days. In other words, the police were given twice the amount of the prosecutor with multiple suspects. Upon completion of this 48 hours or immediately, the police must inform the prosecutor. Nevertheless, except for these types of situations, an apprehension can turn into a detention only by the determination of the prosecutor.

It should also be mentioned that for three years as of July 31, 2018, detention periods for some crimes in the Criminal Code and crimes that fall under the terrorism act or committed as an illegal gang activity, have been extended. Accordingly, the detention period is 48 hours; and if there are multiple suspects, it is four days excluding the time of travel. If evidence gathering or the file being extensive should make it difficult, it can be extended twice, reaching 12 days in some cases.[07]

The prosecutor decides whether or not to issue an indictment based on the evidence collected, including the statement of the accused. If he/she finds that the evidence collected is insufficient, or that no trial may be conducted due to other legal restrictions, no indictment will be filed, and the detainee, if still under custody, must be released. This decision is subject to revision by the presiding judge of the nearest aggravated felony court[08]. The prosecutor can also end detention by asking for judicial control. Or if he decides that judicial control or detention is no longer necessary, he can release the suspect. In addition, if the prosecutor decides that the actions described in the notice and complaint openly do not amount to a crime or if the notice and complaint have vague points or are too general, then he can determine that an investigation is unnecessary.[09]

After the interrogation, if the prosecutor has a strong suspicion that a crime has been committed, he/she will refer the suspect to the judge with a request for pre-trial arrest. In that sense, arrest is a precautionary measure rendered by the judge during the investigation, or by the court of first instance during prosecution (after the approval of the indictment). Pre-trial arrest can be ordered when there is a strong suspicion that a crime has been committed and there is a reason for arrest.[10] Reasons for arrest are as follows: if the suspect or defendant is likely to abscond, hide, or there are circumstances creating that suspicion; if the suspect or defendant’s actions create strong suspicion that he/she will destroy, hide or change evidence, or attempt to pressure witnesses, victims or others. Further, the law provides a catalogue of crimes, where a reason for arrest ‘may be presumed’. These include murder, production and trade of drugs and sexual offences.[11] However, in practice, there is a tendency to order pre-trial detention if the crime falls under one of these in the catalogue without looking for a reason for arrest.

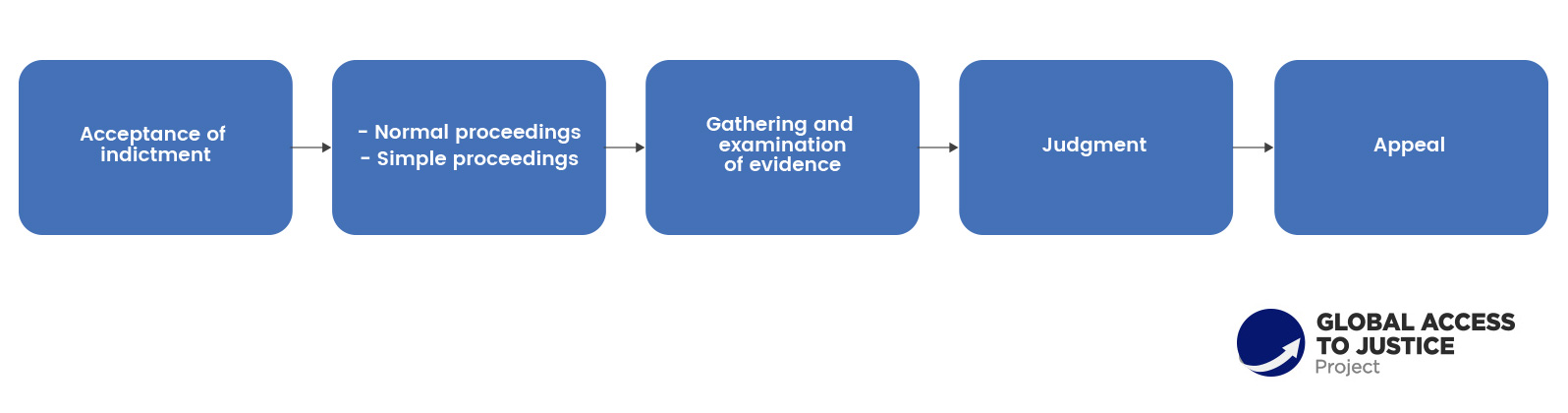

Chart 10. Criminal investigation stage

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

In terms of different proceedings, if the prosecutor does not determine to delay initiating the criminal proceedings, there can be an expedited process for certain minor crimes.[13] The prosecutor must inform the suspect about what that means and only if the suspect agrees in the presence of his/her attorney, the prosecutor may then determine the sentence including a reduction thereof. In other words, the prosecutor is “in charge” here and acts almost like a judge. The court then reviews whether the crime fits the ones enumerated in the CCP and whether the suspect agreed to the process or not.

Another proceeding is called simple proceedings[14] where it is the court that is in charge. In this case, after admitting the indictment, for crimes that require fines and a sentence of maximum two years and less, the court may even proceed without holding a hearing and without asking the opinion of the prosecutor. It should be mentioned that courts of general jurisdiction no longer have prosecutors serving on the bench. Through this procedure, judges act like prosecutors.

Lastly, there is victim offender mediation[15] for crimes that are subject to complaint by the victim. The scope of victim offender mediation has been widened to include some crimes such as physical assault.

Aside from the above proceedings, if at the end of an investigation, the prosecutor decides that there is sufficient evidence to press charges, he/she prepares an indictment and submits it to the court. The legal determination for filing an indictment is less stringent (a sufficient level of suspicion),[16] than the one required for an arrest (strong suspicion).[17] The court may reject the indictment, if so, the prosecutor may amend the indictment and submit, or file an objection.[18] The fact that, in urgent situations, the prosecutor can also order precautionary measures, makes the prosecutor’s role in the criminal justice process more awkward.

Nevertheless, the pre-trial period is reserved for the preparation of the trial. This period extends from the approval of the indictment by the court until the beginning of the first hearing, the date of which is determined by the court, according to its own schedule.[19] The prosecutor formally notifies the defendant of the indictment and the date for the first hearing.[20] During this period, no witnesses or experts will be heard, except in cases where these persons are not likely to be able to appear before the court during the trial – for example, where the witness is terminally ill.[21] In addition, evidence gathering procedures may be completed or repeated, if need be.[22]

The hearing can only begin when all required persons (the judges, prosecutor[23], clerk, and, in cases where counsel is mandatory, the defence lawyer) are present.[24] As a rule, the defendant must also be present during all hearings. The defendant may, however, be excused, if he/she has already provided a statement, if his/her attorney makes a request to that effect,[25] or if the defendant is transferred to a prison facility outside the province of the court due to necessity or health or disciplinary reasons.[26] The statement of the defendant can also be obtained through an online and video connected system. In any of these cases, the proceedings may commence, but shall not be concluded, unless the defendant has been interrogated by the court, or the court can acquit the defendant based on evidence in the file,[27] except in situations where the sentence to be given consists of seizure of property and/or a fine, in which case the trial may be conducted and the sentence given in absentia.[28] The judge or court may order the arrest following a hearing, where the defendant is present.[29]

There is no time limit or legal deadline for completing the investigation of the police.

Chart 11. Criminal case flow chart

3.1.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

3.1.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

One of the main problems with due process indicators is the lack of defence lawyer involvement throughout the criminal justice system, which appears to result from a number of factors, including the failure to inform suspects and defendants in an effective way of their right to a lawyer, and a general lack of public knowledge concerning people’s rights.[30] This is exacerbated by the possibility of continuing the hearing in the absence of an attorney. Judges’ attitude limiting the right to defence also prevail.

Structural problems of the criminal justice system that undermine the rule of law such as backlog and delays remain. Overcrowding in prisons has grown that the government tries to deal with early releases that undermine truth in sentencing.[31]

The media and human rights organizations continue to report police violence. The police are shielded from accountability which leads to impunity. With the lapse into authoritarianism in the country, torture and bad treatment allegations are back. However, in order to start criminal action against public servants, the permission of their superiors is sought which is increasingly not given.

Improper evidence collection by the police has always been a problem. In the past, it was the over-use of phone tapping as part of the interception of communications, after the 2016 coup-attempt it has been replaced by indiscriminate admission of secret communication application called Bylock as evidence of membership in a terror organization even if it was only downloaded and never used. All of this is worrying when one considers that the mechanisms for excluding evidence obtained illegally or unfairly are not strong. The very court that hears the case on the merits is expected to decide whether the evidence was obtained illegally. In fact, the law provides that the judgment should discuss evidence, including illegally obtained evidence, present in the file and explain why it was not taken into consideration.[32] These provisions presuppose that any unlawful evidence will be in the case file from the beginning of the investigation until the conclusion of the trial, but fail to appreciate that, once in the file, evidence, no matter whether it has been illegally obtained, would be difficult to ignore by the court. Illegally obtained evidence should, ideally, be taken out of the court file and deposited elsewhere. In line with this sloppy evidence gathering, courts also resort to rejecting the evidence. Further, defense attorneys cannot collect evidence on their own.

Although there has been wide application of online mechanisms from filing to statement taking, there is still no verbatim recording of hearings. Instead, what happens in the hearings are summarized and then dictated by the judge to the clerk. This does not always reflect the reality of what is happening in the courtroom as judges are inclined to state in the record what the appellate judges are looking for to ensure their judgment is not reversed. Consequently, records are inaccurate, do not correctly reflect the questions and answers of the defendant or witnesses.[33]

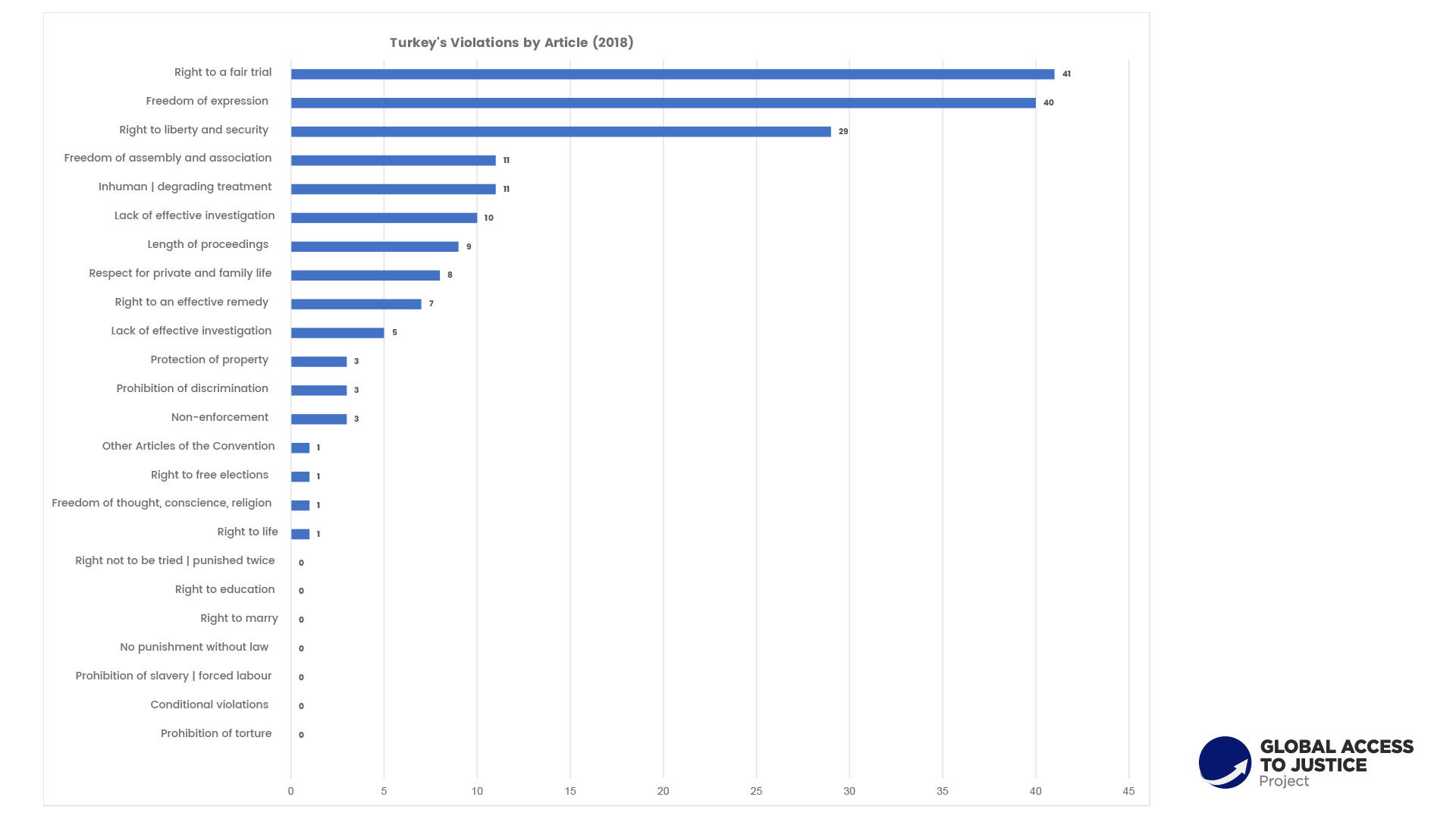

A search of the judgments rendered by the European Court of Human Rights with regard to Turkey with key words such as “access to justice” and “article 6” under criminal cases, ECHR retrieves at least 52 cases in English.[34] In 2018, the number of applications pending before the ECHR has reportedly been around 56,000, with almost 72% of the pending cases concerning six countries, including Turkey (12.6%) as the fourth biggest provider of cases.[35]

Chart 12. ECHR Judgments on Turkey (2018)

| Total of judgments | 146 |

| At least one violation | 140 |

| No violation | 4 |

| Friendly settlements | striking-out | 2 |

| Other judgments | 0 |

When we look closer at the violations, it is seen that Turkey performs worst with regards to Article 6 of the Convention, i.e. right to a fair trial.

Chart 13. Violations by Article

Similarly, a summary of violations compiled by the ECHR[36] by article and state reveals that in 2019, in 96 out of a total of 113 cases, there was at least one violation and 13 of these involved the right to a fair trial.

Similarly, a summary of violations compiled by the ECHR[36] by article and state reveals that in 2019, in 96 out of a total of 113 cases, there was at least one violation and 13 of these involved the right to a fair trial.

Overall, for the period between 1959-2018, Turkey also ranks first on the total number of judgments, with at least one violation in 88% of the cases and with right to a fair trial making up for almost 30% of all violations.

Chart 14. ECHR Judgments on Turkey (1959-2018)

| Total of judgments |

3,532

|

||

| At least one violation |

3,128

|

Article 6 919 cases |

Article 5 755 cases |

| No violation | 81 | ||

| Friendly settlements | striking-out | 213 | ||

| Other judgments | 110 | ||

Especially in the aftermath of the 2016 coup attempt and the following emergency rule, serious human rights violations have been reported by national and international agencies.[37] There have been dismissals from service and arrests among various groups including members of the armed forces, judges and prosecutors, public servants, members of Parliament, journalists, human rights defenders, students and lawyers. Most of the measures adopted during emergency rule after the coup attempt have been limiting the right to defense and were disproportionate.[38] At the national level, according to a recent factsheet published by the Arrested Lawyers Initiative, a volunteer organization for defending rights of lawyers, as of July 3, 2020, 108,200 dismissal decisions have been delivered within thirty months, or approximately 180 decisions per working day.[39] With particular attention to the situation of defense in Turkey, the Initiative also reported that since 2016 coup attempt, more than 1500 lawyers have been prosecuted, 605 lawyers have been arrested and as of February 2020, 345 lawyers have been sentenced to a total of 2158 years in prison mostly on charges of terrorism.[40]

According to another recent report of the Initiative, the use of anti-terrorism legislation has been increasing steadily since 2016. This legislation consists of the provisions of the Turkish Criminal Code as well as Anti-Terrorism Code No. 3713. Article 314 of the Turkish Criminal Code is particularly important in terrorism related investigations and prosecutions as it stipulates that:

(i) Any person who establishes or commands an armed organization with the purpose of committing the offences listed in parts four and five of this chapter, shall be sentenced to a penalty of imprisonment for a term of ten to fifteen years.

(ii) Any person who becomes a member of the organization defined in paragraph one shall be sentenced to a penalty of imprisonment for a term of five to ten years.

(iii) Other provisions relating to the forming of an organization to commit crimes shall also apply in terms of this offence.[41]

Chart 15 shows the increase in the number of charges and verdicts under Article 314 since 2016.

Chart 15. Charges and Verdicts Under Article 314 (2016-2019)

| Year | # of charges | # of verdicts |

| 2016 | 30,766 | 4,949 |

| 2017 | 146,731 | 36,927 |

| 2018 | 115,753 | 108,412 |

| 2019 | 54,464 | 69,740 |

At the international level, the PACE, for instance, defined Turkey’s response to the “unquestionably serious situation” as “disproportionate on numerous grounds”. It was stated that the granted powers were way more excessive than required by the exigencies of the situation and the duration of the state of emergency was excessive, turning emergency measures into permanent changes to the legal framework.[42] The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has also declared that “the sheer number, frequency and the lack of connection of several decrees to any national threat, seems to indicate the arbitrary nature of some measures, and point to the use of emergency powers to stifle any form of criticism or dissent vis-à-vis the Government”.[43]

Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has also declared that “the sheer number, frequency and the lack of connection of several decrees to any national threat, seems to indicate the arbitrary nature of some measures, and point to the use of emergency powers to stifle any form of criticism or dissent vis-à-vis the Government”.[44]

Recently, the undermining of the rule of law reached new proportions such as lower courts refusing to comply with the judgments of the Constitutional Court while the Constitutional Court resisted decisions by the ECHR. Further, despite the immediate release decision of the Court in the case of philanthropist Osman Kavala, the court of first instance resisted that decision. Similarly, the immediate release request of the Court for Selahattin Demirtaş was also resisted.[45]

3.2. Civil Procedure

3.2.1. Overview of civil procedures

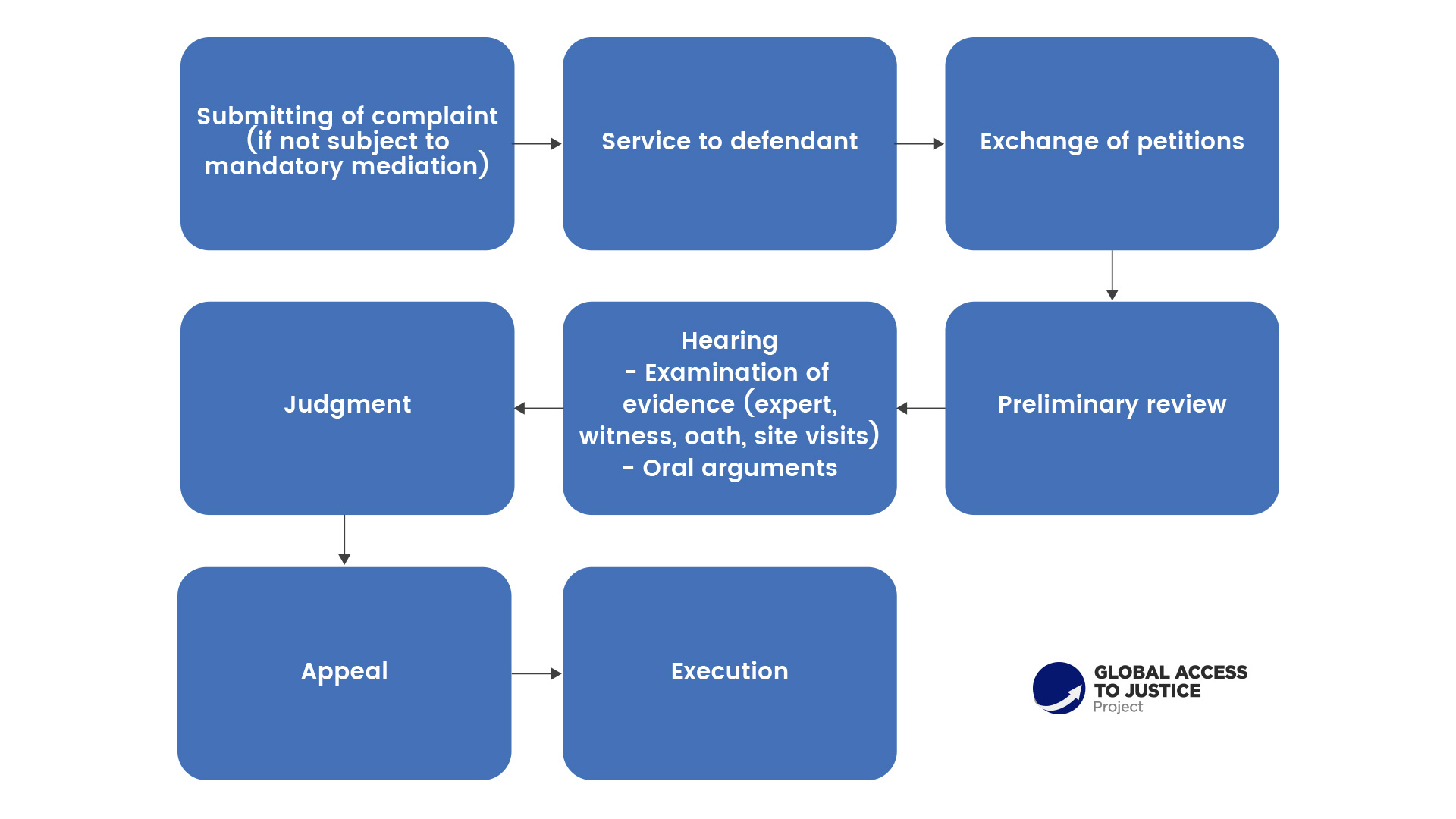

The first instance starts with the filing of a complaint by the plaintiff. Upon receipt of the complaint, the defendant has two weeks to respond. Plaintiff must then file an answer to the reply within two weeks. Finally, the defendant files his/her second reply within two weeks. After this exchange, the court starts its preliminary review which includes procedural objections such as forum and necessary steps for the parties to provide evidence. The court may start investigation of substantive issues only after these procedural issues are completed. This is done in a hearing orally by examination of evidence through one presiding judge if it is a court consisting of three judges. This is the time when witnesses and experts are heard by taking an oath or through site visits. The parties will make arguments about the evidence and finally a judgment will be rendered by the court which will go to intermediate appeal or appeal depending on the dispute amount. The period to file an appeal is two weeks. The judgment will be executed only after becoming final.

On the other hand, there are also simple proceedings that apply in matters that fall under the jurisdiction of civil courts of peace like obtaining injunctions and other temporary measures and reports; all sorts of alimony, guardianship and custody issues; claims arising out of service relations and similar. Simple proceedings may involve reaching a judgment on the basis of the contents of the file, without a hearing. When hearings do take place, their number is limited to two. More than two hearings are allowed only in exceptional circumstances and the time period between the two hearings cannot be longer than one month.

In civil cases, the judge is bound by what the parties bring before the court. This puts him into a rather passive or an umpire position. For parties with attorneys, this role is easier to be played by judges but when it comes to unrepresented parties, they feel the pressure. They cannot assist parties and give legal advice. The below quote from a judge in a research carried out before civil courts of Istanbul puts the dilemma as follows:

“…Let me be forward: we can apply the procedural code strictly. I mean when we apply it, we can apply it very strictly. We do this with the lawyers. But then you cannot discriminate between the party with a lawyer and one without. …We apply the procedure strictly to the party with the lawyer but we do not do the same to the party without representation because (s)he would not know about it…it will lead to the loss of her/his right…otherwise, the citizen will say the judge took the side of the other party because they have a lawyer”.[46]

Chart 16. Basic civil procedure

3.2.2. Encouraging settlement

3.2.2. Encouraging settlement

Parties in a pending litigation can be made aware about mediation and encouraged by the judge or decide on their own to go to a mediator.[47] Further, once a claim is filed, if both parties declare that they will go before a mediator, the court may suspend the file for no longer than three months. This period can be prolonged for another three months.[48] It should, however, be said that the effects of these provisions in terms of cost reduction or fairness to encourage parties to settle or conciliate was rather insignificant. The provision suggests that the parties must choose a mediator on their own which suggests equal contribution to the fees of a private mediator. Further, an economically weaker party may not know a mediator who he/she can sufficiently trust. Therefore, it would have made very little difference in reducing costs or providing fairness for parties with unequal means. This is partly why mandatory mediation was adopted in Turkey as it automatically appoints a mediator for whose fees the state is responsible up to a certain point.

3.2.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

European Court of Human Rights usually finds Turkey in violation of reasonable time issues. In other words, in civil proceedings, including enforcement, it takes too long for claimants to actually reach their right.

In general, enforcement proceedings are conducted pursuant to an act that was taken in toto from a Swiss Enforcement Code dating from 1860s and therefore has many rights and liberties issues. For instance, the execution authority may go to the place of abode of the debtor and have its door opened through a locksmith; exercise physical force against the debtor where necessary. Currently, a new law is being drafted.

Further, in every economic crisis in Turkey, the collection of banks’ debts is made easy given their power and connections in politics. This is usually to the detriment of debtors.

3.3. Alternative dispute resolution

3.3.1. The compulsory diversion of disputes

The compulsory diversion of cases started in Turkey as of January 1, 2018 with the adoption of a law on labour courts.[49] Thus, claims for the collection of receivables or compensation either by the employer or employee or for the reinstatement of an employee were made subject to mandatory mediation. Believing that mandatory mediation was a success in labour disputes, it was later introduced in commercial cases as of January 1, 2019.[50] And finally, as of July 28, 2020, consumer disputes were also made subject to mandatory mediation. It should be noted that mediation is the only ADR mechanism available.

Both mechanisms are government-financed up to a point. If the parties fail to reach an agreement, it is the government that pays the mediator according to a tariff for up to two hours. However, if the parties successfully resolve the dispute, they contribute to the mediator’s fees equally.[51] Courts do not have their own ADR regulations in Turkey. Rather, in major court houses, mediation bureaus are established, and it is their job in mandatory cases to take the application and appoint a mediator (through an automated system). They do not perform the function of a front office. It is the mediator who administers the claim, contacts the parties and then proceeds with the mediation.

These diversions do not seem to be temporary or conditional given the fact that the government views mandatory mediation as a panacea and is determined to introduce in other areas such as family, insurance and energy law. Disputes which have been resolved in mandatory mediation cannot be later brought before a court. Once a mediation agreement is reached, it is enforceable as a court judgment after obtaining a confirmation of enforceability (from the court that shall determine this without a hearing). Further, if the parties, their attorneys and the mediator sign the mediation agreement, then it is enforceable without the need to resort to any confirmation of enforceability from the court.[52] If the parties do not later deliver the promised actions in the mediation agreement, the enforceability process in court may only take into consideration whether the subject matter of the dispute was subject to mediation and the agreement is enforceable.[53]

Parties must apply to the mediation bureau before filing a case in court. Failing to do so, results in the ensuing lawsuit to be denied on procedural grounds. In order to encourage parties to attend the mandatory mediation process, the law adopted an important fee-shifting mechanism. If a party fails to attend the initial mediation meeting, it will pay litigation costs even if it later succeeds in the subsequent litigation.[54] Nevertheless, even this is not enough if one or two of the parties do not feel like resolving the matter in mediation.

3.3.2. The voluntary or consensual diversion of disputes

The oldest alternative dispute resolution mechanism in Turkey has been domestic arbitration ever since it was introduced in the 1920s. However, it did not find much application. It was international arbitration and recognition of arbitral awards that became important in the late 1990s. Nevertheless, this also did not provide much of an alternative for individuals as they remained expensive even for most of the businesses. It is only recently that local arbitration institutions are established in Turkey, but these do not really serve individuals.

Turkish parties mostly agree to the jurisdiction of international arbitration chambers such as the ICC when they sign a contract. Arbitral awards have thus been enforced through the New York Convention as Turkey has been a party to it. Awards have also been challenged before courts. All of this, however, hardly applies to individual citizens.

In criminal law, victim offender mediation was adopted by mid 2000s mainly as a diversion mechanism for lesser crimes. Although it has been since expanded, it is still not seen as a restorative justice mechanism that gives victims voice and offenders an opportunity to make good but rather functions as a diversion. The costs of victim offender mediation are covered by the government but if an offender decides to make amends in monetary terms, it is of course the offender that comes up with the funds.

Mediation in civil matters started first consensually in Turkey. Indeed, the law on mediation was adopted in June 2013. However, in 4,5 years it was observed that there were not enough consensual mediations that eased the burden on the court system. There were also not that many mediation centers established with clear procedures and ethical standards that would create fertile ground for consensual mediation to take off.

3.3.3. ADR Policy Drivers

It would not be wrong to say that lowering the work load of the judiciary was one of the main ideas behind the introduction of mediation in both criminal as well as civil disputes.[55] In addition to the usual problems of delay and ensuing costs, the failed coup attempt in 2016 led to the loss of one third of the judicial personnel. New and inexperienced judges could not make up for the lost experience. Therefore, it should be kept in mind that mandatory mediation in labour, commercial and consumer cases were introduced with all of this in the background. Unfortunately, it creates the danger of viewing mediation as a miracle solution to all the problems of the judicial system.[56] However, human rights and other structural inequalities continue to require the attention of the judiciary. For instance, claims arising from labour accidents or labour related illnesses were excluded from mandatory mediation as these continue to be problems in Turkey.

While saving costs and maintaining relationships were also important drives in introducing mandatory mediation, the insistence on family mediation[57] is purely ideological. As a conservative government, protecting the “family” is important even if this means undermining the rights of women. Indeed, femicides are a huge problem in Turkey but the government is more interested in preventing divorce rather than femicides as evident by the establishment of a commission carrying that name in the Parliament. This has become most evident in the latest attempts to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention, the first European treaty specifically targeting violence against women and domestic violence. Ultra conservative religious groups framed the Istanbul Convention as the culprit for the increase in the number of divorces and the decay of family values. In late July 2020, the attacks against the Convention in the political discourse as well as in the academic, religious circles and the pro-government media led to a serious backlash initiated by the feminist movement in Turkey and owned by a larger populace, particularly on social media. As of August 7, the political consideration to withdraw from the Convention seems to be on halt, but not off the table.

Ethical problems also plague some of the current mediations. For instance, employers are prone to retain one mediator as “theirs” and to ask for her or his appointment in all cases filed against that employer. These do not further access to justice especially for workers in monetary terms who are said to settle for less than they would get in court in return of getting immediate payment. In addition, some mediators are only interested in getting the two-hour fee and do not engage in any meaningful mediation activity, turning the process into a “tick box” exercise. These examples show that there is a lack of understanding about the basic tenets of mediation as well as the fact that ethical rules not only exist to guide mediators and protect parties but also to build public trust in an institution.

Another danger is the creeping legalism since mediation is reserved only for lawyers.[58] This creates the legalization of the debate and practices. Already, sample mediation documents found on the website of the Ministry of Justice resemble court transcripts making things difficult for self-represented citizens. The law on civil mediation provides that if a party needs legal aid to provide for the fees of the mediator, she can apply to the court of peace at the place of the mediation bureau.[59]

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

Dispute resolution before consumer panels has been widened. For certain dispute amounts and depending on whether the dispute is in a metropolitan area or not[60], it is mandatory for parties to go before these panels. Also, consumers may file claims before consumer courts without paying legal dues. The court of cassation is said to differentiate between advance payment made for costs and for evidence. In that way, the court is trying to reduce the amount of advance payments to be made by a party. It is also said that requesting legal aid was made easy (for costs, see below). If the request for legal aid is denied, then the reasons for it must be given by the court.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

4.1. Statutory commitment to access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial

The Constitution as the supreme law sets forth the general framework for all other pieces of legislation. In addition to being democratic, secular and social state governed by the rule of law, Article 5 outlines the particular aims and the duties of the Turkish State as follows:

ARTICLE 5 – The fundamental aims and duties of the State are to safeguard the independence and integrity of the Turkish Nation, the indivisibility of the country, the Republic and democracy, to ensure the welfare, peace, and happiness of the individual and society; to strive for the removal of political, economic, and social obstacles which restrict the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual in a manner incompatible with the principles of justice and of the social state governed by rule of law; and to provide the conditions required for the development of the individual’s material and spiritual existence.

Articles 138 and 139 guarantee independence of the judiciary, courts and judges. Article 10 of the Constitution is the specific equality clause and reads as follows:[1]

ARTICLE 10 – Everyone is equal before the law without distinction as to language, race, colour, sex, political opinion, philosophical belief, religion and sect, or any such grounds.

Men and women have equal rights. The State has the obligation to ensure that this equality exists in practice.[2]

Measures taken for this purpose shall not be interpreted as contrary to the principle of equality.[3]

Measures to be taken for children, the elderly, disabled people, widows and orphans of martyrs as well as for the invalid and veterans shall not be considered as violation of the principle of equality.[4]

No privilege shall be granted to any individual, family, group or class. State organs and administrative authorities are obliged to act in compliance with the principle of equality before the law in all their proceedings.[5]

There are also other relevant clauses that are intended for facilitation of equality before the law and further access to justice:

XIII. Provisions on the protection of rights

A. Freedom to claim rights

ARTICLE 36- (As amended on October 3, 2001; Code No. 4709) Everyone has the right of litigation either as plaintiff or defendant and the right to a fair trial before the courts through legitimate means and procedures. No court shall refuse to hear a case within its jurisdiction.

B. Principle of natural judge

ARTICLE 37– No one may be tried by any judicial authority other than the legally designated court. Extraordinary tribunals with jurisdiction that would in effect remove a person from the jurisdiction of his legally designated court shall not be established.

C. Principles relating to offences and penalties

ARTICLE 38- No one shall be punished for any act which does not constitute a criminal offence under the law in force at the time committed; no one shall be given a heavier penalty for an offence other than the penalty applicable at the time when the offence was committed.

The provisions of the above paragraph shall also apply to the statute of limitations on offences and penalties and on the results of conviction.

Penalties, and security measures in lieu of penalties, shall be prescribed only by law.

No one shall be considered guilty until proven guilty in a court of law.

No one shall be compelled to make a statement that would incriminate himself/herself or his/her legal next of kin, or to present such incriminating evidence.

Findings obtained through illegal methods shall not be considered evidence.[6]

Criminal responsibility shall be personal.

No one shall be deprived of his/her liberty merely on the ground of inability to fulfil a contractual obligation.[7]

Neither death penalty nor general confiscation shall be imposed as punishment.[8]

The administration shall not impose any sanction resulting in restriction of personal liberty. Exceptions to this provision may be introduced by law regarding the internal order of the armed forces.

No citizen shall be extradited to a foreign country because of an offence, except under obligations resulting from being a party to the International Criminal Court.[9]

At the national level, there are also relevant clauses in fundamental laws. In the Code of Civil Procedure, for instance, there are a number of provisions relating to access to justice such as articles on the right to be heard (Article 32), on principle of openness (Article 28), on the right to an interpreter and expert testimony (Article 263), on legal aid (Articles 334-340).

Similarly, the Code of Criminal Procedure is the main piece of legislation that regulates procedural requirements of criminal proceedings and the rights of victims and defendants. Aside from provisions on the exclusion of the judge from proceedings (Articles 22-23) and reasons for disqualification of the judge (Article 24) and the expert (Article 69), there are also regulations on detention, custody (Articles 90-98) and arrest (Articles 100-108), on the procedures for interrogation (Articles 147-148), on the right to a defense lawyer (Article 149), on the right to legal aid (Articles 150-156), on the right to an interpreter (Article 202) and the right to participate in the trial (Article 237). There are also specific provisions on the rights of the victim and the complainant in a criminal case (Articles 233-236).[10]

Turkey is also party to fundamental human rights conventions and according to Article 90 of the Constitution, international agreements duly put into effect have the force of law and no appeal to the Constitutional Court shall be made with regard to these agreements, on the grounds that they are unconstitutional.[11] In 2004, the following addition has been made to the Article: “In the case of a conflict between international agreements, duly put into effect, concerning fundamental rights and freedoms and the laws due to differences in provisions on the same matter, the provisions of international agreements shall prevail”.[12]

In 2012, Turkey has also introduced the right to individual application to the Constitutional Court for further protection of individual rights and freedoms and better implementation of the ECHR provisions.[13]

4.2. Political commitment to access to justice

The concept of “access to justice” has a relatively recent history in Turkey. It became somewhat popular during early 2000s, mainly due to the legal and political momentum triggered by acceptance of Turkey’s candidacy for full membership to the European Union (Tarhanlı, 2011).[14] In fact, in the 2003 National Program for the Adoption of the Acquis under Chapter 24, Priority 24.13 was specifically titled “Continuation of Improvement of the Legal Assistance System in order to Ensure Access to Justice for All Citizens”.[15] In line with requirements of the Priority[16], the then new government under AKP rule promised to take serious measures towards guaranteeing access to justice of citizens.[17] At the policy level, this can be considered as the first significant step towards integrating access to justice into a government program.

Turkey is also a signatory to the Convention on International Access to Justice dated 25 November 1980.[18]

4.3. Responsibility for access to justice policy

The Ministry of Justice is the main executive body responsible for the efficient and fair working of the judicial system. The duties of the Ministry have been set forth in Article 2 of the Code No. 2992 (29.03.1984) on the Organization and Duties of the Ministry of Justice.[19]

The work of the Ministry of Justice has been organized under various Directorates one of which is the Directorate General for Strategy Development which is the body that is particularly relevant for access to justice policies. The Directorate is mainly responsible for the:

- Preparation and the implementation of the judicial budget,

- Financial management of the judicial organization,

- Preparation of basic policy and strategy documents on judicial reform and its execution,

- Execution of national and international projects on judicial reform

Based on principles of the rule of law, judicial independence and impartiality, the Directorate defines its mission as developing and implementing policies to ensure that judicial services are provided in a fair, speedy and efficient manner.

Since its founding in 2006, the Directorate has carried out several projects that are related to improving the efficiency of the judicial system and citizens’ access to justice. Some of these projects are as follows:[20]

- Improved Relations Between Mass Media and the Judiciary in Turkey (Twinning project)[21]

- Legal Clinics[22]

- Strengthening the Legal Aid Services in Turkey (Twinning Project)[23]

- Activating the Legal Protection Insurance System[24]

In 2009, the Directorate published its first Judicial Reform Strategy, followed by updated and revised versions in 2015 and 2019.[25] Nonetheless, the latest Strategy has been deemed as “insufficient” and “cosmetic” by both the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and Human Rights Joint Platform (İnsan Hakları Ortak Platformu – IHOP) as well as the Amnesty International.[26]

4.4. Government access to justice policy

The most recent Judicial Reform Strategy (2019) lists the following headings as the aims of the judicial reform:

- Protection and improvement of rights and freedoms

- Improving independence, impartiality and transparency of the judiciary

- Increasing the quality and quantity of human resources

- Enhancement of performance and productivity

- Ensuring efficient use of the right to self-defense

- Ensuring access to justice and enhancing satisfaction from service

- Enhancing the efficiency of the criminal justice system

- Simplification and enhancement of the efficiency of civil and administrative trials

- Spreading of alternative dispute resolution methods

4.5. Equal access to justice for minorities, immigrants, indigenous peoples or other groups

There is not enough official data on specific groups’ access to justice in Turkey. The available unofficial information mostly concerns the situation of women, LGBTI -albeit to a much lesser extent -, refugees, children and people with disabilities.

A. Women

Turkish legislation guarantees gender equality in all sectors of life.[27] Turkey ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1985. In the 1990s, gender equality improved in public as well as private life particularly with the passing of laws against domestic violence in late 1990s and the amendments to main codes.[28]

Nonetheless, gender discrimination in all areas of social life, poverty, lack of education, inadequate access to information all contribute to the creation and the sustenance of the structural inequalities for women, hindering their access to justice.[29] According to World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report 2020, Turkey ranks 130th out of 153 countries in terms of gender index composed of economic participation and opportunity (136th), educational attainment (113th), health and survival (64th) and political empowerment (109th).[30] Even a darker picture reveals that since 2006, Turkey has improved its score only in the field of health and survival. There is however a significant setback in the other categories.

Although literacy rate has been increasing in Turkey, still women constitute the majority of the illiterate. According to 2019 statistics from TUİK, 5.6% of women over the age of 15 are illiterate. This percentage is 0.9 among men.[31] As we go higher up the academic ladder, the numbers decrease for women. In 2018, while 84.5% of women were recorded to have completed at least one level of education, this percentage was 17.5 for a university degree.

Violence against women is yet another powerful indicator for gender inequality in a society. A 2015 nationwide survey revealed that in Turkey one out of three women has been subject to physical violence by men.[32] According to unofficial numbers collected by feminist initiatives, in 2019 only, 474 women were killed by men.[33] Last but not least, in 2018, the percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in union before age 18 was reportedly 15%.[34] On the other hand, Turkey has in fact one of the most comprehensive and protective pieces of legislation for fighting against violence against women. A product of feminist movement’s hard work, 2012 dated Code No. 6284 To Protect Family and Prevent Violence Against Women is intended to “protect the women, the children, the family members and the victims of stalking, who have been subject to the violence or at the risk of violence, and to regulate procedures and principles with regard to the measures of preventing the violence against those people”. The law also “establishes provisions on protective and preventive measures, financial provisions, and it regulates the establishment and coordination of the Support Services, Centers and the Inter-Agency Coordination”.[35] Nonetheless, as mentioned before, there is a growing political and ideological attack against the legal accomplishments of the women’s movement and the Code No. 6284 is also under constant bash by the conservative groups for being the so-called reason for decay of family values.

Against this backdrop, access to justice becomes a rather challenging matter for women which makes an effective judicial system even more essential.[36] Legal aid, in particular, is a crucial dimension of women’s access to justice given their lack of economic means, physical and social limitations and lack of legal knowledge.[37] In fact, aside from the overall system of gender inequality, the greatest obstacles before women’s access to justice in Turkey are said to be poverty, lack of education, lack of access to information and physical inaccessibility of courts as well as lack of effective translation services at judicial settings.[38] Not surprisingly, civil legal aid provision more often than not involve family law matters and women are the majority of such applications. For instance, Istanbul Bar Association’s data for 2019 show that the 95% of applicants of legal aid are women (12,414 out of 13,029).[39]

There are also Women’s Rights Centers within some Bar Associations which work in cooperation with legal aid bureaus on the delivery of legal aid service in cases such as domestic violence, violence against women and alike, as well as on the provision of professional training of legal aid lawyers who are assigned to such cases.[40] These centers also carry awareness raising campaigns on issues related to women’s rights and cooperate with NGOs, municipalities and other relevant organizations and public institutions working in the field.[41]

Based on the significance of legal aid for women, in 2010 a project titled “Strengthening Women’s Centers for Women’s Efficient Access to Justice” was launched by Human Rights Joint Platform (İnsan Hakları Ortak Platformu – İHOP).[42] The project’s main objective was to increase the capacity of Women’s Centers of Bar Associations in order to increase women’s access to justice. Within the project, there was collaboration with Bar Associations in eastern and southeastern provinces of the country – where violence and discrimination against women are particularly high – for the establishment of women’s centers at these associations. In 2018, another project of IHOP was launched in 2018 with the support of UN Women and it was about strengthening the capacity of lawyers working on cases of violence against women to allow for women’s efficient access to justice.[43] Last but not least, in 2018-2019 a project was carried out by Mor Çatı Women’s Shelter Foundation – in partnership with Istanbul Bilgi University Human Rights Law Research Center. The project was titled “Empowering Access to Justice for Women” and its main purpose was defined as “empowering access mechanisms to justice for women subjected to violence and discrimination by increasing quality in legal assistance”.[44]

B. LGBTI+

Homophobic attacks against the LGBTI+ community in Turkey are not only common but also quite often either undermined by the law enforcement and judicial authorities and/or straight out protected. A 2014 report called “Human Rights Violations of LGBT Individuals in Turkey” prepared as a joint study by Kaos GL Association, LGBTI News Turkey, and the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) (ECOSOC accredited NGO) to be submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council revealed systematic discrimination against LGBTI people. The report reveals that there is a “lack of domestic legal protection for LGBT individuals” and also “state involvement in discrimination against LGBT”. [45]

Nonetheless, the LGBTI+ community is never included in official policy papers or legislative efforts on access to justice. The very limited information on their access to justice is provided by civil society. Social Policies, Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Studies Association (Sosyal Politikalar Cinsiyet Kimliği ve Cinsel Yönelim Çalışmaları Derneği – SPoD) is one of the most influential and productive organizations particularly in the field of access to law and justice. SPoD has been carrying out various projects, trainings concerning LGBTI’s access to law and justice, providing them with legal support, watching trials and lobbying.[46] In 2015, they launched a project called “Strengthening Access to Justice of LGBTI” through which they have carried out a series of activities such as dissemination of technical knowledge, trainings for awareness raising and professional progress, providing legal support to LGBTI individuals as well as following trials. As a result of the project, SPoD has also launched the publication of a series of works on law and access to justice. One of these works is the 2015 report which is one of the most-if not the most-comprehensive studies on the problems LGBTI people face when confronted with the law.[47]

Another significant study in this field was the “Social and Economic Problems of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transsexual (LGBT) Individuals in Turkey” project conducted by SPoD and Boğaziçi University Social Policy Forum. The project intended to reveal the discrimination faced by the LGBTI community due to their sexual orientation and gender identity in different areas of social life, including law and access to justice. For the project, 2875 individuals participated in the online survey and 14 focus group interviews with over 200 people were conducted in 10 cities. The results of the survey on law and access to justice were as follows:

- 1 % of all participants (1324 individuals) reported that they faced discrimination on the grounds of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

- Only 10 % of those who faced discrimination (133 individuals) stated that they filed an official complaint.

- Out of those who filed complaint, only 16.5 per cent (22 individuals) had a satisfactory result.

- Out of LGBT individuals who reported discrimination but who did not file a complaint, 604 of them stated that they thought it would not make a difference, 587 of them stated that they did not want their gender identity/sexual orientation to be known by others, 328 of them stated they did not know how to file a complaint and 209 of them stated that they did not have the necessary money for taking a legal action.[48]

C. Refugees/Asylum-Seekers

UNHCR 2018 Access to Justice Fact Sheet on refugees’ and asylum seekers’ access to justice in Turkey make the following observations regarding the accessibility and quality of legal aid for these groups:

“While an enabling legal framework exists, refugees and asylum-seekers face a number of challenges to access justice with national resources being stretched beyond capacity to provide legal aid to all refugees in need, and refugees lacking information on the availability of legal aid”.[49]

In February 2018, UNHCR has initiated a project in coordination with UTBA. The project was titled “Türkiye’de Mülteci Sığınmacı ve Geçici Koruma Altındaki Kişilerin Adalete Erişimlerinin Desteklenmesi Projesi” and it mainly aimed at increasing access to justice for refugees and asylum-seekers.

The following excerpt from the 2018 Fact Sheet gives more detail about the objectives and the activities of the project:

“As of February 2018, UNHCR and UTBA have initiated a project aimed at increasing access to effective and accurate legal assistance by refugees and asylum-seekers, as well as increase the capacity of Bar Associations to provide legal aid. To ease some of the pressure on the legal aid budgets of Bar Associations, attorney fees, notary, translation and transportation expenses will be covered by UNHCR for a number of priority cases. Following positive feedback from Istanbul, Gaziantep, Çanakkale, Trabzon and Kayseri Bar Associations, five workshops were organized between May and July 2018 attended by some 537 lawyers. Experts from UNHCR, UTBA and UNDP provided technical information, including practical tips and case studies on international protection principles, the national legal framework on international and temporary protection, appeal procedures, application procedures to and jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court and European Court of Human Rights, challenges observed in practice with regards to appeal procedures and provision of legal assistance, mixed migration and push-backs, civil law, the right to employment of asylum-seekers and refugees, protection of women and children under the Turkish legal framework, and communication with refugee clients.

Lawyers attending these workshops are provided with certificates and become part of the project to provide legal aid services for asylum-seekers and refugees. A legal clinic established in Şanlıurfa, which became operational in April 2018, provides legal assistance to asylum-seekers and refugees on a broad range of subjects, including temporary protection procedures, administrative detention, access to rights and civil law matters, as well as supporting NGOs and lawyers through information sessions and case-specific legal counselling. In addition, in line with the Memorandum of Understanding that was signed with the UTBA, UNHCR has established a pool of interpreters equipped to receive calls from across the country whenever interpretation is needed in Arabic and Farsi to facilitate access to legal assistance, and to support lawyers with their oral and written interpretation needs related to their work with refugees.” [50]

The original project was completed in December 2019, however because the project was considered to be quite successful in terms of its impact on enhancing access to justice for refugees, reportedly a new protocol was recently with UNHCR.[51]

D. People with Disabilities

In Turkey, rights of people with disabilities have usually been discussed in the context of access to education, employment opportunities, rehabilitation and state aids. This is usually the framework for scientific and academic works as well. Even among civil society groups working in the field, it is more common to find charity-based works rather than rights-based ones or works with the particular goal of empowerment. Access to justice has not been a specific issue for research or policy either. The Code on People with Disabilities No. 5378, for instance, was enacted in 2005 and it is a crucial regulation for encouraging and enabling people with disabilities to enjoy their fundamental rights and freedoms and allow their equal participation in social and economic life. The Code places obligations on the State for the provision and the delivery of necessary services to people with disabilities to allow for their equal access; however, there is again no particular provision on their access to judicial mechanisms and legal services.[52]

A recent study has been the first fieldwork on the problems of access to justice faced by people with disabilities.[53] In the study, access to justice has been interpreted not solely as access to law and judicial mechanisms, but as an empowerment issue that has to do with learning and demanding your rights and increasing capacity for their execution. The study intended to find out the level of information among people with disabilities about their rights and the available mechanisms they can resort to if they face violations, the accessibility of these mechanisms for these people and the obstacles they confront.

The study shows that people with disabilities have limited access to information on their rights. For those who can have access, legal terminology might be very difficult to understand. Aside from the initiatives of Bar Associations and local municipalities, there is no piece of legislation that regulates the provision of legal services to people with disabilities in a uniform fashion.

People with disabilities are also reported to face difficulty while accessing judicial mechanisms although the Code on People with Disabilities No. 5378 clearly defines “accessibility” to buildings, public spaces, transportation and information systems as a prerequisite for allowing people with disabilities to exercise their fundamental rights and freedoms. Article 7 obliges the State to facilitate accessibility in all areas of public service, including courthouses, law enforcement agencies, prosecution offices, prisons; however, there are still problems with accessibility. The technical equipment necessary for allowing people with disabilities to follow their own trials is still not established in many judicial settings.[54] In addition, problems with efficient sign-language translation services at judicial settings and the legal barriers before holding public officers accountable for discrimination against people with disabilities are also listed as indicators of problems of access to justice.[55]

Another influential project has been launched in 2016 and lasted until July 2019 and it was titled “Supporting Access to Justice for People with Disabilities in Combating Discrimination”. The project was supported by EU Delegation Turkey and European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) with the collaboration of local NGOs working in the field of disability. The main objective of the project was to “improve and strengthen access to justice for persons with disabilities for the full enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms”. With this objective in mind, the following activities were carried out:

- Enhancing capacities of CSOs in supporting equal rights for persons with disabilities through monitoring/reporting, advocacy, legal support;

- Raising awareness on access to services and combatting with discrimination for persons with disabilities;

- Increasing the number of applications made by persons with disabilities, to human rights complaints mechanisms such as Human rights and Equality İnstitution of Turkey and Ombudsman Institution as well as judicial mechanisms.

- Improving the efficiency of CSOs in terms of development of national and local policies, implementation and dissemination of information regarding rights of persons with disabilities.

- Raising awareness on the rights of persons with disabilities in society and providing international exchange of experience between CSOs and relevant institutions.[56]

In December 15-16, 2018, an international conference on access to justice of people with disabilities was organized in Istanbul as part of the project and in 2019 conference proceedings were published. The conference book remains to be one of the most significant contributions to academic as well as practical works in the field.[57]

E. Children/Juvenile

According to data from TUİK, minors have been involved in 511, 247 incidents in 2019. 46% of these minors have been victims whereas 168,250 minors (33%) have been involved in some sort of crime as offender. 15% has been recorded in the system as informants, 3.4% as lost and 2.5% have been in contact with security forces for other reasons.

Within the 33%, the breakdown of offenses has been as follows: 37% bodily harm, 25.6% theft, 8% violation of Passport Code, 6.9% migrant smuggling, 4.6% drug use and sell. Among victims, 57.6% have been victims of bodily harm, 15.2% of sexual offenses, 11% of offenses against family unity, 3.5% of threat, 2.7% of deprivation of liberty, and 2.1% have been victims of theft.

Despite this social context, access to justice for minors has not been a particularly important topic for policy makers or even for scholars.[58] Nonetheless, expert reports reveal serious violations in cases with minors. Civil society has particularly been more active in spotting problems, creating platforms for discussion, raising awareness and producing research-based knowledge on the issue and recommendations for policy.[59]

In 2016, UTBA and UNICEF has also launched a joint program on strengthening access to justice for children. In 2019, a comprehensive report has been published based on the results of the needs assessment study that revealed problems with legal services for minors.[60] The report lists current problems in four main categories:

- Problems with access to legal aid

- Problems with the provision and the use of legal aid

- Problems with the quality of legal aid