National Report

Summary of Contents

1. General Information

“All public power in Sweden proceeds from the people.” This is the opening statement in the opening chapter of the first amendment of the Swedish constitution, the Instrument of Government (in Swedish, Regeringsformen). This phrase sets the benchmark for the description of the representative democracy that is Sweden. Although it is a monarchy, through the years the power of the monarch has decreased to the extent that it is merely symbolic in the present day.[1]

The power structure in Sweden is as follows: people elect representatives to the Swedish Parliament (the Riksdag) and to local government (municipal and county councils) from which legislative power emanates. With support from the Parliament, a Government is formed to perform executive tasks. The Government also has initiative power in suggesting legislation. Chapter 1 of the Instrument of Government also emphasises that all public power is exercised under the rule of law/in conformity with the law.[2]

According to the UNDP Human Development Report, Sweden has one of the highest Human Development Index scores in the world with a value of 0.933. This places the country at number 7 on a worldwide ranking.[3] The index considers components such as life expectancy at birth, expected years of schooling, mean years of schooling and gross national income per capita.[4]

The table below indicates the Swedish gross domestic product for the last ten years in billions of Swedish crowns (SEK) and US dollars (USD).[5] N.B. the figures in SEK were extracted from Ekonomifakta (who extracted it from Statistics Sweden).[6] In 2018, the gross national income per capita was 482 000 SEK (~50 500 US dollars).[7]

Chart 01. Swedish GDP for the last ten years in billions of Swedish crowns (SEK) and US dollars (USD).

| Billions SEK | |

| 2008 | (417 billion USD) 3 988 billion SEK |

| 2009 | (399 billion USD) 3 819 billion SEK |

| 2010 | (424 billion USD) 4 055 billion SEK |

| 2011 | (437 billion USD) 4 179 billion SEK |

| 2012 | (434 billion USD) 4 153 billion SEK |

| 2013 | (439 billion USD) 4 198 billion SEK |

| 2014 | (451 billion USD) 4 313 billion SEK |

| 2015 | (471 billion USD) 4 504 billion SEK |

| 2016 | (482 billion USD) 4 613 billion SEK |

| 2017 | (494 billion USD) 4 724 billion SEK |

| 2018 | (506 billion USD) 4 834 billion SEK |

Using the Gini coefficient, the OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) determined the level of income inequality among countries in the organisation and in 2018 Sweden had one of the lowest levels of income inequality with a score of 0.28.[8]The Gini coefficient is based on the comparison of cumulative proportions of the population against cumulative proportions of income they receive, and it ranges between zero in the case of perfect equality and one in the case of perfect inequality.[9]

Sweden does however have a growing problem of people living in low-income households. From 2008 to 2016, people in Sweden who lived under the EU standard for low-income household increased from 13 to 16 percent. As of 2018, seven percent of the working population of Sweden has an income level below the EU’s at-risk-of-poverty threshold.[10]

As we will observe later in this report, the form of government and the living conditions of the country’s population play a crucial role in access to justice. The principles underpinning the rule of law grant people the possibility of just dispute resolution and criminal justice but they also light the path to securing human rights. Interconnected with the rule of law are the living conditions that, in practice, either impede or facilitate human rights and access to justice.

2. Legal system

2.1. Type of Legal System

The Swedish legal system, albeit traditionally considered a civil law system, does not fit particularly well into the category of either civil or common law.[1] It is not civil, as it does not have a one-piece codification such as Germany’s Burgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB) or France’s Code Napoleon. Sweden enacted the most recent general codification in 1734, parts of which are still valid law today.[2] There are, however, codes (balkar) regarding specific topics, such as the Code of Judicial Procedure, the Environmental Code, the Penal Code and the Marriage Code. On the other hand, some areas of law, such as perfecting security interests in chattels (sakrätt), are mostly the realm of case law with little or no statutory provisions.[3]

However, Sweden does not fit particularly well within the common law designation either, in particular because of the perception of the role of the judiciary. The mixture of statutory and case law, the perceived role of the judges, and the degree of self-regulation fostered into the legal system, are features of the so-called Nordic legal family.[4] The Nordic legal family is distinct from the Anglo-American, Germanic and Romanist legal families, and uses case law in a manner distinct from the Anglo-American systems.[5] Although hybrid, the legal system in the Nordic countries partly falls within the civil law system because of the role of the courts. In theory, the courts simply determine the intent of the legislator, and do not make law. Consequently, the Swedish legal system is based on a separation of political function, but not a separation of political power.[6]

Another aspect that is unique to the Nordic legal family is the quasi-legislative power delegated to private organisations in the areas of labour and employment law with respect to social partners, i.e. employers and employee organisations. The basis for this absence of statutory regulation is that these organisations are seen as being closer to the problems and thus are perceived as having a better understanding of the issues and possible solutions.[7] Self-governance and self-regulation are strong aspects of this model and are found within landlord and tenant law, contract law, insurance law and corporate law.[8]

In the Swedish legal system, areas of law are first categorised as either public or private law as in the Roman law tradition. The former concerns issues between political power, the state, counties and municipalities, and the individual. The latter concerns issues between two private parties. A major distinction between the two is that public law is mandatory (tvingande), while private law is seen as having a gap-filling function (dispositiv) in most case.[9] However, some provisions in private law are mandatory even though, for consumer protection provisions for example, the parties are free to agree to the contrary. The party adversely affected by such an agreement has to use their rights under the mandatory law to have the agreement cancelled, therefore making these protections in private law more quasi-mandatory than mandatory.[10] The periphery between mandatory and gap-filling in specific cases can be somewhat grey as legislative acts concerning private law can have features of a solely public law nature. For instance, the Companies Act (aktiebolagslag 2005:551) and the Land Code (jordabalk 1970:994) encompass sections concerning criminal sanctions for violations of specific provisions of these laws.[11]

2.2. The Swedish Justice System

According to article two of chapter 11 of the Instrument of Government, the Courts have independent status in Sweden[12] and neither Parliament (Riksdag) nor the Government (Regeringen) or any government agency is to interfere in how courts rule on individual cases.[13] Article 6 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), effective as law in Sweden since November 1998, also guarantees the independence of the courts.[14] The courts fall under the administration of the Ministry of Justice and its agency, the National Courts Administration.[15]

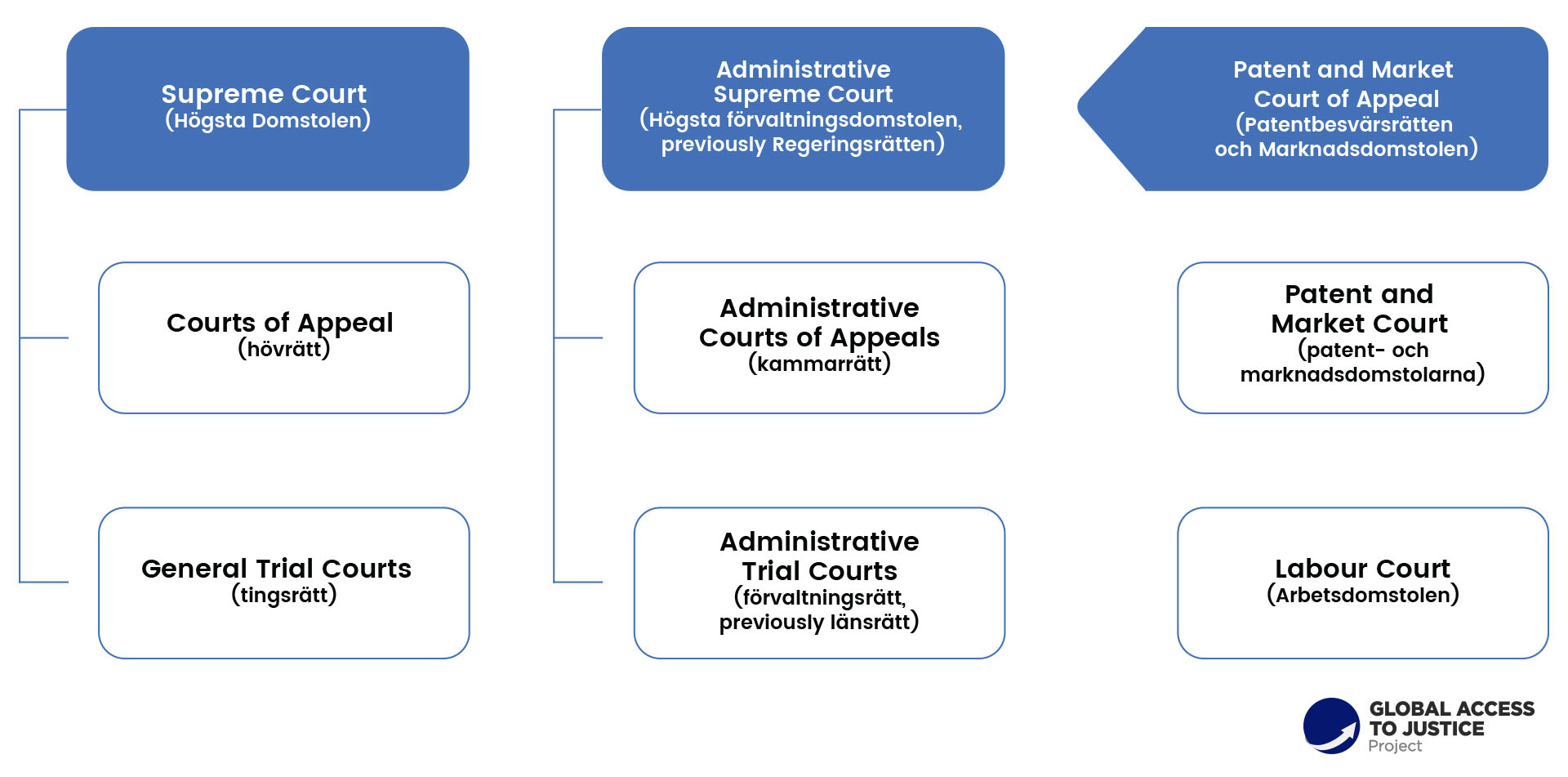

There are three types of courts in Sweden: the general courts, which include district courts, courts of appeal and the Supreme Court; the general administrative courts, namely, administrative courts, administrative courts of appeal and the Supreme Administrative Court; as well as the special courts, which decide disputes within special areas, for example the Labour Court.[16]

There are two parallel court systems, the general courts and the administrative courts. The general courts include forty-eight district courts (tingsrätt),[17] six courts of appeal (hovrätt) and one Supreme Court (Högsta domstolen).[18] The administrative courts include twelve administrative district courts (förvaltningsrätt, previously länsrätt), four administrative courts of appeal (kammarrätt) and one Supreme Administrative Court (Högsta förvaltningsdomstolen, previously Regeringsrätten).[19]

The specialised courts have specific jurisdictions, such as the Labour Court (Arbetsdomstolen);[20] from 1 September 2016 the Patent and Market Court (patent- och marknadsdomstolarna),[21] and the Patent and Market Court of Appeal (Patentbesvärsrätten och Marknadsdomstolen)[22] came into being. Other specialised courts are the five land and environment courts (Mark- och miljödomstol) and the Land and Environment Court of Appeal (Mark- och miljööverdomstolen), the seven maritime courts (sjörättsdomstol), the three migration courts (migrationsdomstol) and the Higher Migration Court (migrationsöverdomstol).[23]

Some of the specialised courts, such as the Patent and Market Court of Appeal, connect to the general or administrative systems, while others have no such connections. For instance, the Labour Court is normally the court of first instance as well as the sole appellate court in cases regarding employers and employee organisations with the Supreme Court having no general jurisdiction over its decisions. The Supreme Court, however, can technically allow a petition to set aside a judgment of the Labour Court (resning), but has yet to do so.[24]

2.2.1. The General Courts

The general courts include the district court as the court of first instance, the court of appeal as the court of second instance and the Supreme Court as the court of third instance.[25]

Chart 02. Cases handled (filed, determined and pending) by the general courts of first instance 2014-2018[26]

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Cases handled | 175,538 | 170,408 | 171,706 | 180,248 | 190,226 |

2.2.2. The Administrative Courts

The administrative courts handle cases concerning disputes between individuals and public authorities and are organised under a three-tier system. The first court tier is the Administrative Court, the second is the Administrative Court of Appeal, and the third and highest is the Supreme Administrative Court. There are 12 administrative courts and four administrative courts of appeal. On 15 February 2010, the former 23 County Administrative Courts were reorganized into 12 Administrative Courts. At the administrative courts in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö and Luleå, there are migration courts that hear alien and citizenship cases as the court of first instance, whilst the Migration Court of Appeal is attached to the Administrative Court of Appeal in Stockholm and is the highest instance for such cases.[27]

Chart 03. Cases handled (filed, determined and pending) by the administrative courts of first instance 2014-2018[28]

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Cases handled | 308,820 | 294,344 | 321,572 | 368,982 | 392,987 |

| of which Migration cases | 58,819 | 56,694 | 83,381 | 118,350 | 122,873 |

| of which compulsory care cases | 39,360 | 40,523 | 40,634 | 40,065 | 41,521 |

Migration cases have had the most significant increase between 2014 and 2018 most probably due to the so-called refugee crisis of 2015. The increase in migration cases handled in the administrative courts is important to note because the legal aid scheme for administrative cases is only available for either migration or compulsory care cases (see section 5.2 on Legislative framework for legal aid). For this purpose, it is interesting to note that the compulsory care cases handled during the same period remained constant.

Chart 04. The Court Systems

2.3. Parallel Justice Structures

There are different minorities in Sweden such as Muslims, Jews, Sikhs, Roma and Sami people. These groups use formal but unofficial structures for ceremonies such as weddings and for related dispute resolution. For instance, the Roma use their own tribunals (Kris) and other forms of alternative dispute resolution (Divano) for resolving issues concerning weddings and property disputes. However, both Kris and Divano practices are not recognised by the Swedish State as official law or legal structures. The Sami people are an exception in that they were indigenous to these lands before official borders were created, and in fact have had their own Parliament since 1993. The 31 members of the Sami Parliament Plenary Assembly are elected through general elections every fourth year. More than 8000 of Sweden’s estimated 20 000-35 000 Sami are now registered in the Sami Parliament electoral register.[29] The Sami Parliament exists as a way to recognise the indigenous status of the Sami and to ensure their participation in political life through representative participation. The Sami people, however, do not have a parallel justice system and therefore are subject to the Swedish courts and justice system for resolving disputes. As far as access to justice is concerned, Sweden has been criticised by various international organisations for its handling of minorities’ rights (see section 2.7.1).

2.4. The Structure of the Legal Profession

Any person can provide legal advice even without formal legal education.[30] However, most practicing lawyers have a law degree, which consists of a Master of Laws (jurist kandidat) LL.M., attained after four and a half years of studies. The Swedish Bar Association (Sveriges advokatsamfund) (SBA), which was founded in 1887, has approximately 5800[31] members, of which 25% are women.[32] In order for a lawyer to use the title of licensed attorney (advokat) they have to be in good standing with the SBA; it is a criminal offence to use the title advokat without being a member of the SBA.[33] The law requires certain legal advisors to be licensed attorneys, including bankruptcy trustees, public defenders and supervising legal counsel paid by the state to victims of crimes (målsägandebiträde). There are some exceptions to the requirements to be admitted to the SBA.[34] At the European Union law level, Council Directive 89/48/ECC recognises higher education diplomas attained on completion of professional education and training of at least three years duration. In addition, there is Directive 98/5/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council that facilitates the practice of the profession of lawyer on a permanent basis in a Member State other than that in which the qualification was attained – the “Establishment Directive”.[35]

Section 7.5.1 of The Code of Professional Conduct for Members of Swedish Bar Association states that “Only an Advocate may be appointed to be a member or deputy member of the board or become a shareholder or partner in a law firm company”.[36] The board of the SBA can dispense of this rule where the managing director of a law firm organised as a limited liability company does not have to be an advocate as long as they have undertaken to observe the regulations applicable to the law practice including good advocate conduct. In such a case, the Managing Director may also sign on behalf of the company but only jointly with an advocate. However, no one is authorised to sign on behalf of a law firm company without the participation of one of its active advocates, except in the circumstances set forth in Chapter 8, section 36 of the Companies Act.[37] Notwithstanding the provisions in Section 7.5.1, a managing director who is not an advocate and who is granted an exemption by the SBA, may become a shareholder or a partner of such company provided such ownership may only cover less than ten percent of the capital and represent less than ten percent of the voting power. Furthermore, such ownership compels the managing director to transfer his shares or share to the other owners upon termination of the employment.[38]

The Council of Europe European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) report from 2018 indicated the number of lawyers per 100,000 habitants. In Sweden, the number was 58 in 2016, which can be compared to 69 in Finland and 147 in Norway.

The report highlighted a 4% increase in 2012-2014, a 5% increase in 2012-2016 and a 1% increase in 2014-2016 in the number of lawyers in Sweden.[39] The number of lawyers in any given country may, or may not, be an indication to the level of litigiousness in the country. Thus, a higher number of lawyers may suggest a society where the use of law is more significant than a society with a lower number of lawyers. However, other factors may influence the number of lawyers without indicating a significant level of litigiousness in the general population, such for example, the presence of a significant legal and financial services market.[40]

2.4.1. Legal representation in Court

The Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure (Rättegångsbalken, RB) states that a person who in light of the case and previous experience is “knowledgeable and conscientious” is eligible to perform legal representation. The “knowledgeable and conscientious” can refer to this person being knowledgeable about the law and, also, not having been committed of any serious criminal offence.[41] In addition to this, the person must not be a minor, a bankrupt or under legal custodianship (förvaltarskap) in the Children and Parents Code (Föräldrabalken), must speak Swedish and live in Sweden or the European Economic Area or Switzerland.[42] These provisions are in reference to civil cases and do not mandate legal representation. The Code of Judicial Procedure, chap. 21 also stipulates that a person may represent himself or herself in a criminal case but that a public defender may, under conditions we will see in section 5.7, be provided to represent their interests (CJP, chap. 21, section 3).[43]

Paralegal or legal officer is a certificated title received after spending two years in a higher vocational education institution. In Sweden, paralegals perform administrative duties in courts, law firms and companies.[44] Paralegals can represent individuals in courts if they fulfil the requirements of “knowledgeability and conscientiousness” (see the section above on legal representation). The duties performed by paralegals at law firms or companies are, among others: keeping contact with clients, government agencies and courts, searching and presenting information on cases, constructing, examining and classifying contracts and other legal documents, writing judicial enquiries, accounting and keeping a diary/record on a case.[45]

Paralegals at courts have the task of keeping contact with other courts, government agencies, legal representatives and different parties in cases. They can also work administratively preparing and processing criminal cases, civil cases, bankruptcy cases and others. In some instances, they are able to suggest verdicts in small (simple) cases, conduct simple judicial enquiries and act as recording clerks at hearing sessions.[46] There are no available statistics on paralegals as the professional title was established in Sweden fairly recently (education for paralegals began in 2006).[47]

The affordability of the legal services that lawyers provide depends on the income of individuals seeking legal counsel and also on the nature of the case at hand. In criminal cases (if you are accused of committing a serious crime or if you are a victim of a crime), you are entitled to a public defender or a legal counsel for an injured party (see section 5.7). The charges for these legal services are met by the state. A public legal counsel is also afforded to those who face other mandatory interventions in their personal life by the state such as asylum cases and compulsory institutional care (see section 5).

2.4.2. Judges in Sweden

The Instrument of Government in the Swedish Constitution specifies that courts are independent of any state entity in their decision-making in individual cases.[48] The Government, following proposals by the Judges’ Proposals Board (Domarnämnden), appoints judges to permanent positions.[49] Judges are required to have a bachelor’s degree in law and many appointed judges have undergone specialised judicial training, such as serving at courts of appeal and administrative courts of appeal and district courts/administrative courts.[50]

Judges may be dismissed from their position if due to gross negligence of duty (or criminal offence on duty) they are unfit to occupy their position. They may also be dismissed in cases of mandatory retirement age (currently 67 years) or impeding medical conditions. Judges may be transferred to equal positions if they are obliged to depart from their position due to organizational reasons.[51]

The latest census on judges in Sweden showed the following: there were 1700 judges, 62 percent are women and 38 percent are men. The average age of women in the position is 42 and for men the average is 45.[52]

3. Process and proceedings: overview

3.1. Criminal Procedure

In Sweden, the prosecution service is under the authority of the Swedish Prosecution Authority (Åklagarmyndigheten). It employs about 1,400 staff, 950 of whom are prosecutors while the rest are engaged with various support work.[1] The Swedish Prosecution Authority answers directly to the Ministry of Justice.[2] All prosecutors are independent in their decision-making, which means that a senior prosecutor cannot influence decisions a subordinate prosecutor might make in a case for which the subordinate is in charge.[3] Public prosecutors are recruited directly by the Swedish Prosecution Authority via their website.[4] Recruitment may be internal and/or external. To be eligible a candidate must have a law degree, have completed Swedish notary merit at a district court and be a Swedish citizen.[5] Candidates are assessed through structured interviews, a personality test and two performance tests.[6] Part of the recruitment process includes background checks regarding criminal records, census records, family relationships, grades and exams.[7] In Sweden, the earliest one can start earning state retirement pension is 61 and there is no upper limit. One has the right to work until the age of 67, however, one can work for longer if there is agreement with one’s employer, and one continues to earn pension rights.[8]

3.1.1. The Criminal Investigation Process

The Code of Judicial Procedure (rättegångsbalk 1942:740) regulates procedural law in the Swedish legal system.[9] The authority responsible for a criminal investigation depends on the severity of the crime committed. If it is a minor offence then the police conduct the investigation from start to finish. If the matter investigated is of a serious nature, then the prosecutor is responsible for conducting the investigation.

Once a crime has come to the attention of the police, a criminal investigation (brottsutredning), also known as a preliminary investigation (förundersökning), starts. The objective of a preliminary investigation is to ascertain whether there is a suspect and whether there is sufficient evidence to initiate prosecution.[10] Once the preliminary investigation is concluded, the prosecutor evaluates whether there is sufficient evidence to bring a court case against the suspect.[11] The prosecutor makes decisions concerning arrest.[12] In cases where there are statutory grounds to arrest a person, and in urgent cases, the police may make an arrest.[13] The arrested person must be interviewed as soon as possible. Immediately after interview, the prosecutor must decide whether the person should be detained or not. If the person is not detained, they must be released immediately.[14] If a person is arrested or detained by the order of a prosecutor, he or she is normally placed in police custody at the nearest police station. However, if a person is arrested or detained by order of a court, he or she is normally placed in a detention centre under the authority of the Swedish Prison and Probation Service.[15]

A prosecutor may issue an order for detention for a person awaiting a detention hearing in the court. Section 13 of chapter 24 of the Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure also states that “The detention hearing may never be held later than four days after the suspect was apprehended or the arrest order was executed”.[16] A prosecutor may also detain a person if doing so is of great importance for the investigation, in which case they must submit a request for a detention order to the court no later than 12 o’clock on the third day after the decision to detain.[17] The prosecutor’s decision to arrest and detain requires that the person be suspected, with probable cause, of an offence carrying a potential penalty of at least one year’s imprisonment.[18] The court can issue a detention order if the offence is punishable by at least two years’ imprisonment. When a court has issued a detention order, the prosecutor must institute criminal proceeding within 14 days.[19] However, the court can extend this period.[20]

Section one of chapter 24 of the Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure provides that any person suspected on probable cause of an offence punishable by imprisonment of one year or more may be detained. This can happen if, in view of the nature of the offence, the suspect’s circumstances, or any other factor, there is a reasonable risk that he or she will flee or evade the proceedings, obstruct the investigation, or continue his or her criminal activity.[21] Furthermore, section two in chapter 24 of the Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure provides that any person suspected on probable cause may be detained regardless of the nature of the offence provided that his or her identity is unknown, he or she does not reside in Sweden and there is a reasonable risk that he or she will avoid proceedings by fleeing the country.[22]

The police have to file charges within six hours against people detained for disturbing public order or who are considered dangerous, and within 12 hours against those detained on other grounds. The police may hold a person for six hours for questioning or as long as 12 hours, without a court order, if deemed necessary for the investigation. After questioning, authorities must either arrest or release an individual, based on the level of suspicion. If a suspect is arrested, the prosecutor has 24 hours (or three days in exceptional circumstances) to request continued detention. Authorities must charge an arrested suspect within 48 hours and begin initial prosecution within two weeks unless there are extenuating circumstances.[23] Swedish law does not place a time limit on pre-trial detention. However, if the prosecutor has not brought charges within 14 days a new pre-trial detention hearing must take place. The length of time that it takes to conduct a preliminary investigation largely depends on the nature of the crime being investigated. In a case of drunk driving the preliminary investigation can often be completed within half a day. However, a serious financial crime may take several years before the preliminary investigation is completed.[24]

Criminal hearings are generally open to the public. However, if sensitive information or information that is protected by confidentiality is presented, or when the interests of the investigation must be protected, the court can make a decision behind closed doors, or ‘in camera’.[25] The defendant is normally expected to attend the hearing. However, under certain circumstances he or she can be excused, such as if there is disruption to public modes of communication, sudden illness or unforeseen circumstances. Additionally, the suspect is not bound to attend the hearing if the case can be disposed of without his or her presence. Section 15a in chapter 46 of the Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure provides that the case may be adjudicated in absentia if the sanction is no more than a fine, a maximum of three months’ imprisonment, a conditional sentence, or probation, or such sanctions jointly. Also, if the defendant has fled or is in hiding or if his or her mental condition render their presence unnecessary.[26]

3.1.2. Critiques of the Criminal Investigation Process

When it comes to due process in criminal investigations and access to justice, Sweden has been criticised by the UN and NGOs for among other things indefinite detention practices. In 2016, the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) criticised Sweden for police use of excessive force when apprehending a suspect i.e. excessive use of pepper spray, truncheon blows, violent pushing of the apprehended person to the ground, tight handcuffing, and lifting a detainee by the handcuffs.[27] Sweden was additionally criticised regarding prison and detention centre conditions where some inmates, particularly foreign nationals, complained of being locked in their cells for up to 23 hours per day, three days in a row, for unofficial collective punishment following fights between two or more inmates.[28] In two remand prisons, the CPT also noted that most cells had no in-cell sanitation and some inmates complained about delays in using toilet facilities.[29] In 2016, Sweden was criticised for indefinite pre-trial detention.[30] It was noted that in Sweden there is no legislation putting a limit to pre-trial detention and it was shown that in extreme cases there were pre-trial detention instances spanning 1,400 days with over 1,000 days in isolation.[31] In 2015, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD)[32] criticised Sweden, and the UK, for arbitrarily detaining Julian Assange. Furthermore, a report by Civil Rights Defenders on immigration detention and pre-trial detention found numerous shortcomings in the Swedish system.[33] These shortcomings were mostly in regards to detained victims whereby there were inadequate measures to inform them of their rights, to identify them and to investigate crimes committed while in detention.[34] Similarly, staff were not adequately trained to identify victims and to document injuries sustained while in detention. Limited access to interpreters was also highlighted as an issue. Moreover, there was a consensus among lawyers that such detainees are a low priority in the justice system.[35]

3.2 Civil Procedure

The Code of Judicial Procedure (CJP) (Rättegångsbalken), stipulates the provisions of civil procedure.[36] The following is the procedure for civil cases at first instance or district courts (tingsrätt):

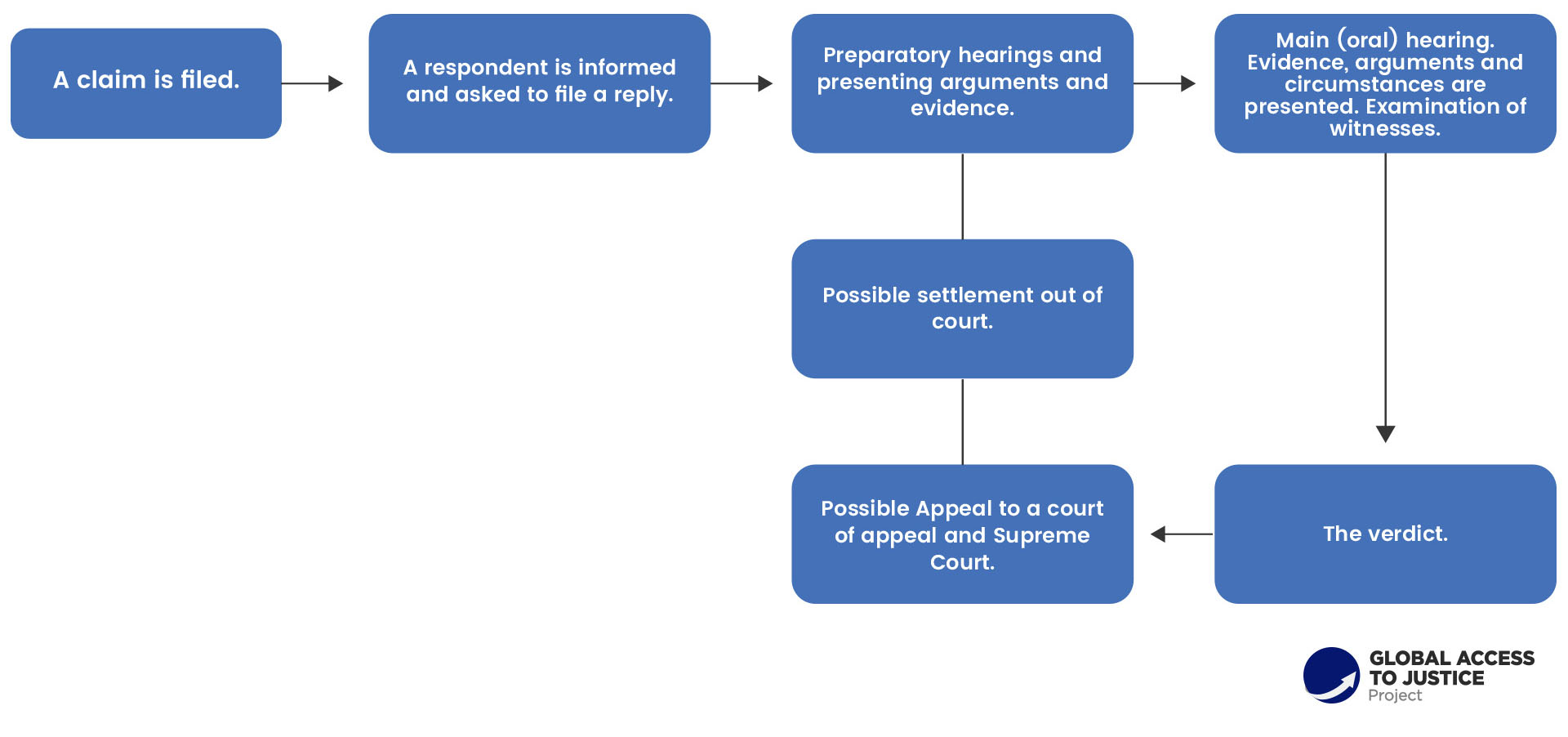

A plaintiff files a claim (stämningsansökan) at the court where they reside. The contents of the plaint, according to the Code of Judicial Procedure (chap. 42, section 2), are (i) a clearly stated claim (ii) a description of the circumstances on which the claim is based (iii) a statement of evidence (iv) an indication of the circumstances that give the court jurisdiction over the matter.[37]

The next step is for the court to inform the respondent of the filed plaint (including plaint, circumstances and evidence) and request a defence (svaromål) (CJP, chap.42, section 5). The defence from the respondent must contain: (i) possible procedural impediments (e.g. the case has already been determined or the plaintiff does not possess the right to litigate) (ii) whether the respondent concedes or contests the plaint (iii) if the respondent contests the plaint, on what grounds they contest, a statement regarding the plaintiff’s stated circumstances and the respondent’s own statement of circumstances and (iv) the respondent’s statement of evidence.[38]

The procedure continues with one or several verbal preparatory hearings (förberedelse) or through exchange of documents (skriftväxling) to map out the claims, circumstances and evidence of both parties and determine the disagreement and the scope of any necessary investigation.[39] After concluding preparatory hearings, the court can, if there are grounds for this, work to convince the concerned parties to arrive at a settlement out of court (förlikning) or solution by compromise (samförståndslösning).[40] To avoid stalling tactics, e.g. by repeatedly presenting new claims and evidence, the court can set a time limit for parties to decide definitely what claims and evidence they want to invoke (CJP, chap. 42, section 15). This is called preclusion (preklusion). After the deadline set by the court, the court admits new claims and arguments only under exceptional circumstances (CJP, chap. 42, section 15).

At the conclusion of the preparatory hearings, it is time for the main hearing (huvudförhandling) where the court is presided over by one (in small claims cases) or three legally trained judges (CJP, chap.1, section 3a). At this point, both parties state their claims, present their statements of circumstances (or arguments) as well as presenting evidence, and have the opportunity to examine witnesses before their closing arguments.[41] A main hearing may take place immediately after the (verbal) preparatory hearing with the consent of both parties, unless the matter is obvious, in which case the main hearing can take place without both parties’ consent (Code of Judicial Procedure, chap. 42, section 20).

The court then delivers its verdict. If the action is one which is amenable to out-of-court settlement (dispositivt mål), such as breach of contract, the decision of the court must be based solely on the pleaded claims and the arguments presented in court (Code of Judicial Procedure, chap. 17, section 3). In an action not amenable to settlement out-of-court (indispositivt mål), such as a child custody case, the court is not obligated to only consider claims and arguments presented by the parties[42] but may consider other circumstances and arguments relevant to the case.

A dissatisfied party can appeal to the court of appeal (hovrätt), within three weeks of the date of the verdict (CJP, chap. 50, section 1). For the court of appeal to adjudicate the case, leave to appeal (prövningstillstånd) is required (CJP, chap. 49, section 12). The court of appeal will grant leave to appeal where: (i) the court of appeal has reason to doubt the correctness of the district court’s verdict; (ii) the correctness of the decision cannot be determined without an appeal; (iii) if it is important for the adjudication process that the case is tried by a higher court instance; or (iv) if there are exceptional reasons for the court of appeal to try the case (e.g. if the district court is suspected to have committed a serious mistake) (CJP, chap. 49, section 14).[43] An appeal to the Supreme Court (Högsta domstolen) can only be considered (i) if it is important for the adjudication process that the case is tried by the Supreme Court and (ii) if there are exceptional reasons such as if there are grounds for a new trial or grave procedural errors have been committed or the verdict of the court of appeal is due to obvious gross negligence/grave mistake (CJP, chap. 54, section 10).[44]

Below is a chart for the proceedings in a civil case:

Chart 05. Civil Case Proceedings

The court should always work for a fast resolution of the case, which is often the reason for the court to discuss with the litigating parties ways to reach a settlement out of court during the preparatory phase of the civil case. A judge may help parties to negotiate the terms of a settlement (förlikning) or alternatively a special mediator (särskild medlare) (CJP, chap. 42, section 17) may be hired by the court to mediate the settlement, with the consent of both parties.[45]

A special mediator is, in regards to the court, an independent (often) lawyer appointed by agreement of both parties and the court with the task of settling the differences between the parties and finding a satisfactory agreement for both parties during a limited period. The costs of the mediator are borne by the litigating parties.[46]

If the parties still cannot settle the case with help of the special mediator, the court continues the processing of the case. If the parties reach a settlement with the help of the mediator, the court revokes the claim and closes the case.[47]

Special mediation is different from mediation (medling), which occurs where one or several parties, with the help of a third party (a mediator), negotiate an agreement with conditions with which parties must comply. Parties may seek enforceability from the court, i.e. that terms agreed upon may be enforced by the court (Swedish Act on Mediation, chap. 7-12).

The advantage of a settlement and of special mediation is that they considerably reduce the strain on the court system of small claims matters. The costs of arranging main hearings can be avoided and there is reduction of processing time for cases. Another advantage, especially in special mediation, is that the procedural rigour of main hearings can be replaced with negotiation on terms of settlement in private between the two litigants (main hearings are otherwise public).[48] The costs of legal representatives can be reduced if the process of litigating can avoid extended preparatory and main hearings and be limited to meeting in private with a special mediator or legal representatives on a few occasions.

The main disadvantage of out-of-court settlement and special mediation might be an unequal financial positions between litigants. One party might be able to present a team of specialised lawyers and be able to negotiate terms that benefit them because they can afford the legal fees of highly skilled lawyers while their counterpart is perhaps reliant on legal aid and thus might not be entirely free to choose their own legal representatives. The alternative is choosing to litigate in court, which comes with the risk of losing the case and thus being forced to pay one’s own legal fees and those of the opponent (CJP, chap. 18, section 1).[49]

The goal of Swedish civil procedural law is delivering correct and just resolutions of conflicts. The justice system should meet this objective using procedures that are as simple, fast and inexpensive as possible. The rule of law is dependent on procedural law following this main structure.

In practice, civil (as well as criminal) proceedings follow several principles that together make Swedish proceedings rule of law compliant. The adversarial principle (kontradiktoriska principen) secures the right of litigants to be heard by the court and the right of access to all relevant documents in the case (in order for parties to counter arguments and evidence).[50]

The principle of immediateness (omedelbarhetsprincipen) ensures that the court only delivers verdicts based on the facts presented in the main hearing (cases amenable to out-of-court settlement).[51]

The principle of concentrated proceedings (koncentrationsprincipen) means the main hearing should proceed without unnecessary interruptions until the case is ready to be determined. Cases that do not need more than three days to determine have a window of one week to be determined. In cases that require more than three days, the court must have main hearings three times a week until it determines the case (CJP, chap. 43, section 11).[52]

The principle of oral presentation (muntlighetsprincipen) requires the main hearing to be presented orally. Parties may present arguments in writing only if the court finds the written argument to facilitate the understanding of the argument or if it otherwise is reasonable in context (CJP, chap. 43, section 5).[53]

The principle of free appraisal of evidence (principen om fri bevisprövning) means that the court is not bound by any law on the assessment of evidence. The court is free to value the presented evidence and decide what has been proven, as long as they provide the reason for the assessment in their verdict (CJP chap. 35, section 1).[54]

Lastly, the principle of public access to official records (offentlighetsprincipen) requires the court to make proceedings in the court open to public access, unless the nature and/or circumstances of the case require the hearings to occur behind closed doors (CJP chap. 5, section 1) (regulated in the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act).[55]

In addition to these principles, the Swedish courts as a public authority can be subject to critique by the Parliamentary Ombudsmen whose tasks are to “ensure that public authorities and their staff comply with the laws and other statutes governing their actions”.[56] The Parliamentary Ombudsmen can issue criticism to courts that they deem to endanger the rule of law (see above), e.g. as a result of slow and deficient processing of cases.[57] The Ombudsmen conduct inquiries (due to someone filing a complaint against an authority) and deliver decisions in the form of critical findings and suggestions of compliance.[58]

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

The Swedish Government Official Report of 2007[59] concerning alternative dispute resolution (special mediation and settlement out-of-court, see section 3.2) states that these measures are to create a structure of dispute resolution outside of the justice system in order to offer solutions that are better suited to the parties in individual cases and to the nature of those cases. The courts, the Swedish National Board for Consumer Complaints (Allmänna Reklamationsnämnden), arbitration tribunals, and various organizations that offer mediation can be governed by rules and regulation that are not suited to all civil cases; making it possible to resort to alternative and simpler methods of dispute resolution also leads to the reduction of case overload for these government bodies.[60]

The main issue with the court working to encourage people to engage in alternative dispute resolution is that it requires people to consult legal counsel and potential mediators, of whom there are insufficient numbers considering that there are increasing numbers of people ineligible for legal aid in Sweden (legal expenses insurance does not cover legal advice and minor legal assistance).[61] Furthermore, insurance does not apply to criminal cases or disputes that may be examined by administrative authorities, specialist courts, or the administrative courts.[62]

Chapter 18, section 8a in CJP does address the danger of this unequal position and partially remedies it by waiving the rule of repayment for pre-trial judicial costs (costs of legal consultation) in small claims cases. In small claims cases, the losing party is not obligated to repay an amount exceeding the equivalent to one hour of legal consultation (regulated in the Legal Aid Act).

In earlier legislation and drafts to legislation, it was reasoned that the court would have the weaker party’s interest in mind during small claims cases, making the presence of legal counsel unnecessary. Ensuing criticism from legal experts did however point out that the benevolence of judges could not replace legal counsel and their advice to clients (for example, a legal counsel can assess whether the individual should initiate legal proceedings in the first place). In addition to this, the waived costs did not change the fact that weaker parties (e.g. in consumer vs. company cases), still were at a disadvantage against companies with the resources to appoint legal counsel.[63]

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

In sections 3.2 and 3.3, we discussed alternative dispute resolution methods as a way of simplifying or bypassing conventional legal proceedings in Sweden.

In conclusion, a court sponsored out-of-court settlement process between litigants with equal legal representation (state funded legal aid would however need improvement in this respect) appears to be a good solution to simplify legal processes and make them less expensive for all parties involved. This alternative resolution would fortify access to the legal system for financially or otherwise socially vulnerable groups and reduce the costs of the court system. This option would also provide a forum where litigants can negotiate terms of engagement and settlements on a relatively equal footing.

4. Access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial

In the Constitution of Sweden (Regeringsformens 1 kapitel 9§), it is stated that courts and administrative authorities must take into account everyone’s equality before the law as well as comply with objectivity and impartiality. The ECHR establishes the principle of access to justice through the right to a fair trial in Articles 6 and 13 and the EU does the same through Article 47 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The Department of Justice holds the overall responsibility for access to justice in Sweden. Our understanding is that there is strong political commitment to access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial in Sweden.

Sweden ranks among the highest countries in the world in The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index. In 2019, Sweden was ranked number four after Denmark, Norway and Finland. The Rule of Law Index measures eight factors of rule of law: constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice.[1] In addition, according to European Social Survey (ESS), Swedes have high trust in the police and courts in general, and seem to believe that the justice system is legitimate. Even those who had high rates of contact with the police in Sweden had high levels of satisfaction with the police. However, results for the question about how fair the courts are to majority versus minority race/ethnic groups, shows that Swedes believe individuals from different ethnic groups are treated differently in this criminal justice system; they believe someone from a minority group would be more likely to be found guilty.[2]

Research on discrimination within the justice system in Sweden is scarce but has shown for example that people from minority backgrounds are disadvantaged in their contacts with the Swedish justice system[3] and that Afro-Swedes, Muslims and Roma experience racial/ethnic profiling by the police.[4] In the following section on the legal aid system, we will discuss strengths and limitations of access to justice, including access to justice for different groups in society. In the later sections of this report, we will discuss several limitations to access to justice and the possibilities for individuals to have ‘access to justice’ in practice.

5. Legal aid system[1]

5.1. History of legal aid

The first Swedish law on the right to an attorney when suspected of a crime and held in detention was introduced in 1906, which is considered relatively late from a European perspective.[2] This law was replaced in 1919 with a law concerning the appointment of legal assistance for those held in remand prison. At the same time, in 1919 Sweden passed the first legislation providing free legal aid in civil cases to poor people[3] and also included provisions concerning free legal aid in criminal cases (when not being detained). The Law on Free Trial (Lagen om fri rättegång, 1919:367) was in use between 1920 and 1973, but during these years, it was subject to several restrictions because it was deemed too costly. Thus, the law has been described as relatively restrictive.[4]

In 1942, the reform of The Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure (Rättegångsbalken), replaced the law from 1919 on the right to legal assistance for those held in remand prison and introduced today’s system of public defense counsel. In contrast to the previous law, the individual’s income would no longer be assigned any significance.[5] As Wejedal points out, it was not until then that the right of public defense counsel was fully implemented in the law.[6]

At the end of the 1960s, the discussion on legal aid was influenced by Scandinavian welfare ideology.[7] However, prior to 1973 there was no statutorily unified system of civil legal aid in Sweden.[8] The purpose of the Legal Aid Act (1972:429) that came into force in 1973 was to equalize access to legal services by enabling everyone to obtain legal assistance in any case where legal aid was needed.[9] The legal aid of that time was part of the generous welfare programs developed in the early 1970s, and included assistance for most legal problems including advice and minor assistance. It was also open to most of the population.[10]

The Swedish legal aid scheme up until the middle of 1990s has been described as “probably the most generous and comprehensive scheme internationally”.[11] Legal expenses insurance was integrated into household insurance policies in response to pressure from the labour movement in the 1960s. It was designed to fill gaps in public legal aid by providing legal aid to middle-income earners who might be excluded from public legal aid because of their income, and to cover costs that were not covered by public legal aid, such as costs awarded by the court in unsuccessful civil cases.[12] At this time, legal expenses insurance was not widely used, and most Swedes relied on public legal aid.[13] In addition to the regulation of criminal legal aid and civil legal aid, in 1988 provisions on counsel for injured parties were incorporated into a special law for victims of sexual assaults, and later on expanded to other categories of crimes (Lag om målsägandebiträde, LMB).

In the current Legal Aid Act (1996:1619), which came into force in December 1997, the Swedish government introduced a reform to legal aid policy in an effort to cut public spending, and by extension to change the way Swedes responded to common legal problems. One of the goals of the legal aid reform was to achieve major cost savings, since Sweden was undergoing the worst recession since the 1930s.[14] The more limited resources were mainly to be allocated to those in most need of legal aid.[15] The reform did not affect all forms of legal aid: assistance in criminal cases and to victims was maintained. Other welfare policies were not changed as much as legal aid policies.[16] The overarching change in the reform was to make the legal aid scheme secondary to legal expenses cover provided by individuals´ household insurance. This means that the claimant in a dispute should first turn to their insurance company; anyone with legal expenses insurance covering the case in question would not receive legal aid.[17] However, the reform did not, as Regan points out, include a requirement on insurance companies to expand the cover they were offering. The reform presupposed that insurance companies would continue to offer legal expenses insurance to existing policy-holders in the future. Despite major changes in the legal aid scheme, the reform caused little public protest, apart from that voiced by the Swedish Bar Association.[18] The reform also separated legal aid from other forms of legal assistance, such as public defenders, public counsel, and counsel for injured parties.[19]

Another aim of the legal aid reform was to make the legal aid fee vary according to the income of the applicant; it was to be calculated in relation to the costs of legal counsel and paid regularly to the appointed counsel.[20] The new law also included other changes to the entitlement criteria for legal aid. Among other things, up to two hours’ counselling had to precede an application for legal aid. The annual income limit for entitlement to legal aid was reduced from 26 000 USD to 22,000 USD (249,000 to 210,000 SEK). Even so, more than 80% of the population were entitled to legal aid, on the basis of their income.[21] In 1999 the income limit for entitlement to legal aid was raised to 27,200 USD (260,000 SEK).[22]

The 1997 Legal Aid Act also introduced a requirement that there must be special grounds for legal aid to be granted in cases relating to divorce and related issues, to child maintenance, to business owners as regards business activities, and to cases handled abroad.[23] Many family law disputes no longer qualified for legal aid in the new legal aid scheme and an alternative form of dispute resolution was introduced. The allowance for employing counsel was also limited to a maximum of 100 hours, with very limited opportunity for increase.[24]

In the middle of the 1990s, prior to the reform of legal aid, Sweden had more than one hundred publicly employed lawyers working in twenty-eight bureaux at the county level.[25] The state-financed legal aid bureaux were closed down in 1999 on the grounds that the state should no longer engage in the practice of law.[26]

As regards the welfare state, the 1997 reform of the Legal Aid Act singled out legal services from other welfare reforms in the retreat from quasi-universal and comprehensive coverage, as well as the shift from public to private protection.[27] The current legal aid law is fundamentally different from the previous law in that, from being tax-funded legal aid in the previous law, it has become mainly privately funded through insurance premiums.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

In civil cases, Sweden has a combination of public and private cover for legal expenses. Legal expenses insurance (Rättsskydd) is part of household insurance policies, and it can pay part of the costs of legal representation in certain types of case under litigation (for more information on the legal expenses insurance see 5.11). Those without household insurance, or whose insurance does not cover the particular case, can, in certain circumstances, be entitled to publicly funded legal aid (Rättshjälp). The right to state funded legal aid counsel in civil matters (Rättshjälpsbiträde) is regulated in the Legal Aid Act (Rättshjälpslag 7 §). The right to public defense counsel (Offentlig försvarare) in criminal cases, is on the contrary regulated in the Swedish Code of Judicial Procedure (RB 21 kap. 3 a § 2 st.). Victims of crime may be appointed a counsel for an injured party (målsägandebiträde), according to the Act concerning Counsel for an injured party (LMB 1 §). In addition, a public counsel (offentligt biträde) can be appointed in certain cases within administrative law, mainly concerning compulsory care and immigration law. In general terms, the right to the different forms of legal aid is based on an assessment of the need for legal counsel. The right to publicly funded legal aid is based on an income ceiling, but the other three can be granted regardless of income. Legal aid in civil and criminal cases will be further discussed below, as to some extent will the right to public counsel and counsel for injured parties.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

The Court, according to the Code of Judicial Procedure, appoints a public defender in criminal cases if the crime of which the subject is reasonably suspected carries a sentence of no less than six months in prison and the suspect requests a public defence lawyer. The suspect can make a request for a public defender to the person in charge of the investigation (usually a prosecutor but potentially also a police officer) or directly to the district court where the case is prosecuted (see section 5.7).

In order to obtain civil legal aid it is necessary to apply to the Legal Aid Authority, which provides legal aid under the Legal Aid Act, or directly to the court if the case is already before the court (which is the most common situation, see section 5.8.3).

The Legal Aid Authority is a national authority, with eight staff members working on legal aid decisions and handling payment of legal aid costs. In addition, the Legal Aid Authority handles the demands when someone is found guilty of a crime or loses a dispute and is obliged to pay part of the state’s costs.

How legal aid is delivered in Sweden is further explained in section 5.7 (criminal legal aid) and 5.8 (civil legal aid).

5.4. Legal aid budget

The legal aid budget differentiates between public defenders, public counsel, counsel for injured parties and counsel under the Legal Aid Act. The costs of public defenders in criminal cases is the largest allocation and amounted to 154 million USD (1 475 million SEK) in 2018. Public counsel in administrative cases involving individual freedom and personal integrity (involuntary care and immigration), amounted to 54 million USD (515 million SEK) and counsel for injured parties to 39 million USD (369 million SEK). The same year, legal aid under the Legal Aid Act cost the state 26 million USD (248 million SEK).[28] Thus, the budget for legal aid in civil cases is the smallest of the four types. Altogether, in Sweden, the total costs for legal aid (including the four forms mentioned above) was approximately 273 million USD, which represents slightly more than 27 USD per capita during 2018.

5.5. Legal aid providers

Johnsen differentiates between judicare which is legal aid delivered by private lawyers and salaried legal aid provided by public employees.[29] Salaried legal aid no longer exists in Sweden (see 5.1); citizens are only offered judicare. In other words, all lawyers providing legal aid are in private practice.

Any person can provide legal advice even without formal legal education.[30] However, in Sweden, only lawyers with the title ‘advokat’ (referring to members of the Swedish Bar Association, see section 2) can be appointed as the public defender in a criminal court case (Code of Judicial Procedure, chap. 21, section 5).[31] Regarding non-criminal legal aid the requirements are less restrictive. According to section 26 of the Legal Aid Act, the legal aid counsel appointed can be a lawyer, an associate in a law firm or any other appropriate person. In other words, no formal qualifications are required. As Barlow points out that means that, in theory, a legally unqualified person can provide legal aid services, if the person is considered suitable.[32] However, the Legal Aid Authority or the court assesses legal counsel who are not lawyers or associates of a law firm for their suitability as representatives.[33]

The legal representative’s remuneration is based on an hourly rate adopted by the government. In 2018 this was 144 USD (1,380 SEK) (excluding VAT) for those approved for Swedish F-tax (entrepreneurs who pay their own preliminary tax and social security contributions) and 110 USD (1050 SEK) (excluding VAT) for those not approved for F-tax. In criminal court cases, the amount is double on weekends, for example when a client is held in custody.[34] The hourly rate represents the minimum amount that a lawyer will charge per hour in ordinary cases not covered by legal aid. In other words, three times the rate would hardly raise an eyebrow in business law.

5.6. Quality assurance

Decisions taken by the Legal Aid Authority can be appealed to the Legal Aid Board (Legal Aid Act 44§). The Board consists of five members: a chairman who is a judge, two lawyers and two other members, all appointed by the government (Legal Aid Act 48 §). The decisions taken by the Legal Aid Board cannot be appealed (Legal Aid Act 44§). Decisions on civil legal aid taken by the court can be appealed to a higher court (Legal Aid Act 44§). Decisions on civil legal aid can be appealed by the applicant as well as the Chancellor of Justice (Justitieombudsmannen) (Legal Aid Act 45 §).

The Chancellor of Justice, has an external oversight where the overall responsible is to monitor that the legal aid system is not used in a way that has not been intended. This includes ensuring that legal aid is not granted when it should not be done and that the compensation of public funds to lawyers, including public defender in criminal cases, does not exceed what is reasonable.[35] When Barlow compared the oversight of legal aid within the Nordic countries as well as with UK and Republic of Ireland, Sweden was described as having “the most finely tuned checks and balances”.[36]

However, when it comes to mechanisms for monitoring the quality of work by legal aid providers, this is limited to proactive monitoring by the Bar Association’s Disciplinary Committee. They only deal with complaints against their own members. In addition to the disciplinary supervision, the Swedish Bar Association also supervises its members in a proactive manner, regarding a number of areas, e.g. issues of organization, information security, client funds, professional indemnity insurance, conflict of interests, continuing professional education, anti-money laundering, issues of inside information, pricing and information on legal services. This is done in order to strengthen the legitimacy of the Bar’s supervision, to enhance the support to members, to protect continued independence and self-regulation, and to fulfil obligations under Swedish law. The supervision can be initiated both on special reasons and on random grounds and be carried out either by a written procedure or by predetermined firm visits (dawn raids do not occur). 175 law firms were scrutinized in 2016-2018, which means that 4 875 lawyers (2 944 advocates and 1 931 associate lawyers) has been supervised.[37]

Public defenders always have to be lawyers with the title ‘advokat’ (referring to members of the Swedish Bar Association) (see section 2 and 5.7) and will then be under the monitoring of the Swedish Bar association. Non-criminal legal aid, public legal aid counsel and public counsel, however, do not have to be members of the bar association (see section 5.5). For non-bar members there is no official disciplinary committee. However, the Legal Aid Authority do some monitoring of legal aid providers who are associated with a law firm. The Legal Aid Authority take references before the counsel is appointed as well as later if they get indications that the legal aid is not provided does not work well.[38]

5.7 Criminal Legal Aid

5.7.1. Scope of Criminal Legal Aid

When a suspect is notified of the allegations that he/she faces and is arrested, he/she is entitled to a public defence lawyer (offentlig försvarare) (CJP, chap. 21, section 3a). The suspect may appoint a lawyer of his/her choice (CJP, chap. 21, section 3).

According to CJP, chap. 18, section 18, if the preliminary investigation leads to suspicion on reasonable grounds (skäligen misstänkt) of an individual, he/she and his/her defence lawyer must be notified of this when being interrogated.

However, Wejedal[39] points out that only persons suspected on reasonable grounds are entitled to public defence lawyers (state funded) during the preliminary investigation. This means that the police, without the presence of a defence lawyer (because the person is not entitled), can interrogate a person (even young suspects) on a lower degree of suspicion. This, according to Wejedal, “increases the risk of potentially wrongful convictions, based on false confessions and/or self-incriminating statements made under the early stages of interrogation without access to a defence lawyer”.[40]

The defendant is entitled to be represented by a public defence lawyer during the entire main hearing/trial and if the defendant is convicted, the representation by the public defence lawyer continues in the event that the defendant wishes to appeal to a higher court (CJP, chap. 21, section 8). CJP, chap. 21, section 3b stipulates that a “previous defendant” is entitled to a public defender if: (i) according to CJP, chap. 58, section 6a, the prosecutor decides to or has the opportunity to reopen the investigation into the defendant’s involvement in the crime; or (ii) there are other exceptional reasons. This means that even after conviction and enforcement, a person is entitled to a public defender if there may be a new trial.

In criminal proceedings, the victim of a crime is called the ‘injured party’. A counsel for the injured party (målsägandebiträde) can be appointed by the state according to the Act on Counsel of an Injured Party (Lag om målsägandebiträde) (CJP, chap. 20, section 15). The counsel advocates for the interests of the victim during the proceedings and acts as support (Act on Counsel of an Injured Party, section 3), for example by being present during interrogations and examinations in court and advocating for damages. The cost of the counsel is mostly covered by the state (for work done, loss of time and reimbursement of other expenses). The Swedish Bar Association advises injured parties to obtain an assessment on costs of the counsel in cases where, for example, the counsel must travel often and long distances during the process.[41]

The criteria to obtain a counsel is: (i) if a person is the victim of a sexual offence, unless it is clear that the person does not need counsel; (ii) if a person is the victim of a crime against life and health or a crime against liberty and peace, for which the penalty is a prison term, or the victim of theft, robbery and other acquisitive crimes; or (iii) if the person is a victim of a crime for which the sentence is imprisonment and, due to the personal life and other circumstances of the victim, they need counsel (Act on Counsel of an Injured Party, section 1).

Witnesses due to testify in court are not entitled to state-funded legal aid, however courts do provide witness support. Usually, witness support is provided by charitable organisations, whose staff are trained to provide help, information and support during the proceedings. For example, they inform witnesses about the procedure during the main hearing, who the involved parties are and where they are seated and about how the witness’ expenses can be reimbursed by the court.[42]

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

A public defence lawyer is appointed by the state if the crime of which the subject is reasonably suspected carries a sentence of no less than six months in prison and the suspect requests a public defence lawyer (CJP, chap. 21, section 3a). A public defence lawyer must also be appointed: (i) if, in light of the investigation, the suspect needs one; (ii) if the possible sentence is unclear and the sentence might be one that is not a fine or a suspended sentence or similar; and (iii) if there are other exceptional reasons due to the personal circumstances of the suspect or the case (CJP, chap.21, section 3a).

The main rule is that if a defendant is convicted, he/she owes the state for the cost of the public defender that the state provided (CJP, chap. 31, section 1). The third paragraph of this section however, states that the convicted person is not obligated to pay back more of the cost of the public defender than the fee they would have payed if they used the legal aid scheme according to the Legal Aid Act (CJP, chap. 23 & chap. 38). The fourth paragraph in chap. 31, section 1 of the CJP also states that the amount of restitution by the offender can be reduced in consideration of the nature of the crime and the financial situation of the offender.

Studies in the neighbouring countries of Finland, Norway and Denmark show that debts to the state such as judicial costs and indemnity to victims (legal debts) are factors which limit the social reintegration of many ex-offenders. Todd-Kvam[43] highlights the impact of legal debts on the mental health of ex-convicted persons, citing psychosocial apathy as a consequence of long-term indebtedness. Aaltonen[44] and Olesen[45] discuss long-term debt as a risk factor of re-offending and anti-social behaviour among ex-prisoners upon re-entry into conventional society. The collection of debt to the state upon employment risks decreasing an ex-offender’s motivation to stay in the legal labour market.

5.7.3. Process for obtaining criminal legal aid

The court is in charge of appointing the public defence lawyer of the suspect’s choosing, unless there are exceptional reasons not to comply with his/her wishes, such as if the public defence lawyer does not have the appropriate qualifications (CJP, chap. 21, section 5). A person may not be appointed as a public defence lawyer in a case if they have been financially connected to the suspect in a manner that disqualifies him or her from adequately representing the interests of the client (CJP, chap. 21, section 3).

The right to criminal aid is related to the degree of suspicion and to the nature of the crime. In practice, this means that the right to a public defence lawyer is unequivocal beginning at the stage where the person in charge of the investigation notifies the suspect of the crime they are suspected of committing, but only if the suspicion is of the degree of reasonable grounds.[46]

Wejedal (2017) raises a concern with these provisions because there is a legal possibility that the state could arrange the investigation to postpone access to a lawyer by simply notifying the suspect of the charges at the end of the criminal investigation. This means that the state could regard a person as a suspect during most of the investigation yet only notify the person that they are a suspect on reasonable grounds late in the proceedings. The person might have been interviewed earlier in the proceedings and incriminated himself or herself without the presence of a public defence lawyer. The alternative is, however, no more appealing, i.e. investigators notify the person subject to investigation early in the proceedings and make it easier for them to, potentially, erase incriminating evidence.[47]

In 2019, an EU directive on legal aid was adopted in the Swedish Code of Procedure, according to which the prosecutor can appoint an interim public defender immediately after the arrest and detention of a suspect (if the suspect requires one) (Ministry Publications Series 2017:53).[48] This is due to the fact that the prosecutor otherwise has to file a request for a public defence lawyer at the court and wait for the court to process the need for a public defence lawyer (CJP, chap. 21, section 4a).

Appeal against denial of a public defence lawyer is regulated by CJP, chap. 49, section 5, paragraph 1 and CJP, chap. 49, section 6. To appeal one has to file a complaint immediately after the decision by the court (if the decision is given while the accused is at a hearing) or at the latest one week from the day the person received knowledge of the court’s decision. Failure to comply with this time limit leads to the person no longer being able to appeal (CJP, chap. 49, section 6).

As indicated above, a public defence lawyer is appointed by the court upon request by the suspect, which is implicitly optional. However, the court appoints a public defence lawyer if the suspect needs it because of the nature of the case or for otherwise exceptional reasons. In this case, if the prosecutor for the reasons indicated previously deems it necessary with the presence of a public defence lawyer, files a request to the court to appoint one.

This is another area of concern. If a suspect does not exercise their right to a public defence lawyer, the information received from interrogations with the suspect without the presence of a defence lawyer (before the prosecutor requests and the court grants it) can be used against him or her later in the proceedings, which might be in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights.[49] Precedent from a Swedish court of appeal does, however, state that courts should take into consideration that information was obtained during this kind of interrogation, when evaluating evidence.[50] Depending on the instance, the use of public defenders varies to certain degrees.

The following are statistics on determined criminal cases that featured a public defence lawyer in the years 2009-2018:[51]

Districts courts – 458 889 cases (~52% of all criminal cases)

Courts of Appeal – 76 119 cases (~84% of all criminal cases)

Supreme Court – 15 846 cases (~41% of all criminal cases).

5.8. Civil Legal aid

We distinguish between three forms of legal aid in non-criminal proceedings: publically funded civil legal aid, legal expenses insurance (LEI) and public counsel in migration and compulsory care cases. The first two are considered to be civil legal aid (legal cases handled in the public courts, although public legal aid can in theory also be granted in administrative cases) and the third as legal aid in administrative cases (legal cases handled in the administrative courts). Before we go into a detailed description of legal aid under the Legal Aid Act, we will briefly mention the law regulating public counsel (offentligt biträde) for involuntary institutional care and migration/asylum cases. According to the Act on Public Counsel (Lag 1996:1620), legal counsel can be appointed in accordance with special regulations to be found mainly in the compulsory care laws and in the Aliens Act. The compulsory care acts regulate involuntary institutional care of minors living in troubled conditions (Care of Young Persons Act) and of adults with severe substance abuse (Care of Abusers Act) or suffering from mental health problems (Compulsory Psychiatric Care Act). A person subjected to compulsory care can receive a public counsel appointed by the court. The Aliens Act specifies that a public counsel can be appointed in cases concerning, for example, refusal of entry and expulsion. A public counsel shall be appointed for the person subjected to these regulations, unless it can be assumed that there is no need for counsel. Public counsel will be briefly discussed below in relation to legal aid in administrative legal cases. Legal expenses insurance is dealt with under 5.11, Alternative sources of legal assistance.

5.8.1. The scope of the public legal aid scheme

To be eligible for publicly funded civil legal aid you have to meet certain criteria: for example your ‘financial base’ must be less than 27,200 USD (260,000 Swedish Krona – SEK) a year and you must not have legal expenses insurance covering the issue. Legal aid is not granted if your financial situation would have enabled you to take out insurance. Legal aid also applies primarily to private individuals.

This means that legal aid legislation is based on the assumption that the market supplies appropriate insurance policies, and that individuals actually take out insurance.[52] Today, 96% of the Swedish population above the age of 16 have household insurance. In other words, most of the Swedish population is protected by legal expenses insurance. However, young people (16–29 years) and people born abroad are significantly less likely than the average population to have household insurance.[53]

The right to legal aid is governed by the Legal Aid Act (1996:1619). Public legal aid covers all legal matters (rättslig angelägenhet) not specifically excluded in the law (the restrictions are presented below). While legal expenses insurance is limited to cases under litigation, public legal aid has a wider application. However, Renfors et al. (2012) argue that in practice it does not make much difference since many of the issues that would come into question as ‘legal matters’ not requiring litigation, for example, marriage contracts and wills, are in any event excluded in the Legal Aid Act.

Applications for legal aid are decided by the Legal Aid Authority, unless the matter is already before a court. In that case it is the court that decides on legal aid. Section 2 of the Legal Aid Act states that an application for legal aid must be preceded by consultation with a lawyer or other legal practitioner (a minimum of one hour and a maximum of two hours). Exceptions can be made if it is clear that such consultation is unnecessary. The consultation fee paid by the applicant is set at 170 USD (1,628 SEK) per hour in 2015. The fee can be reduced to half if the individual’s income is less than 7 800 USD (75,000 SEK) per year. In the case of people under 18 with no income or capital, the consultation fee can be waived by the Legal Aid Authority.[54] The application for legal aid is filed jointly with the legal counsel doing the consultation.

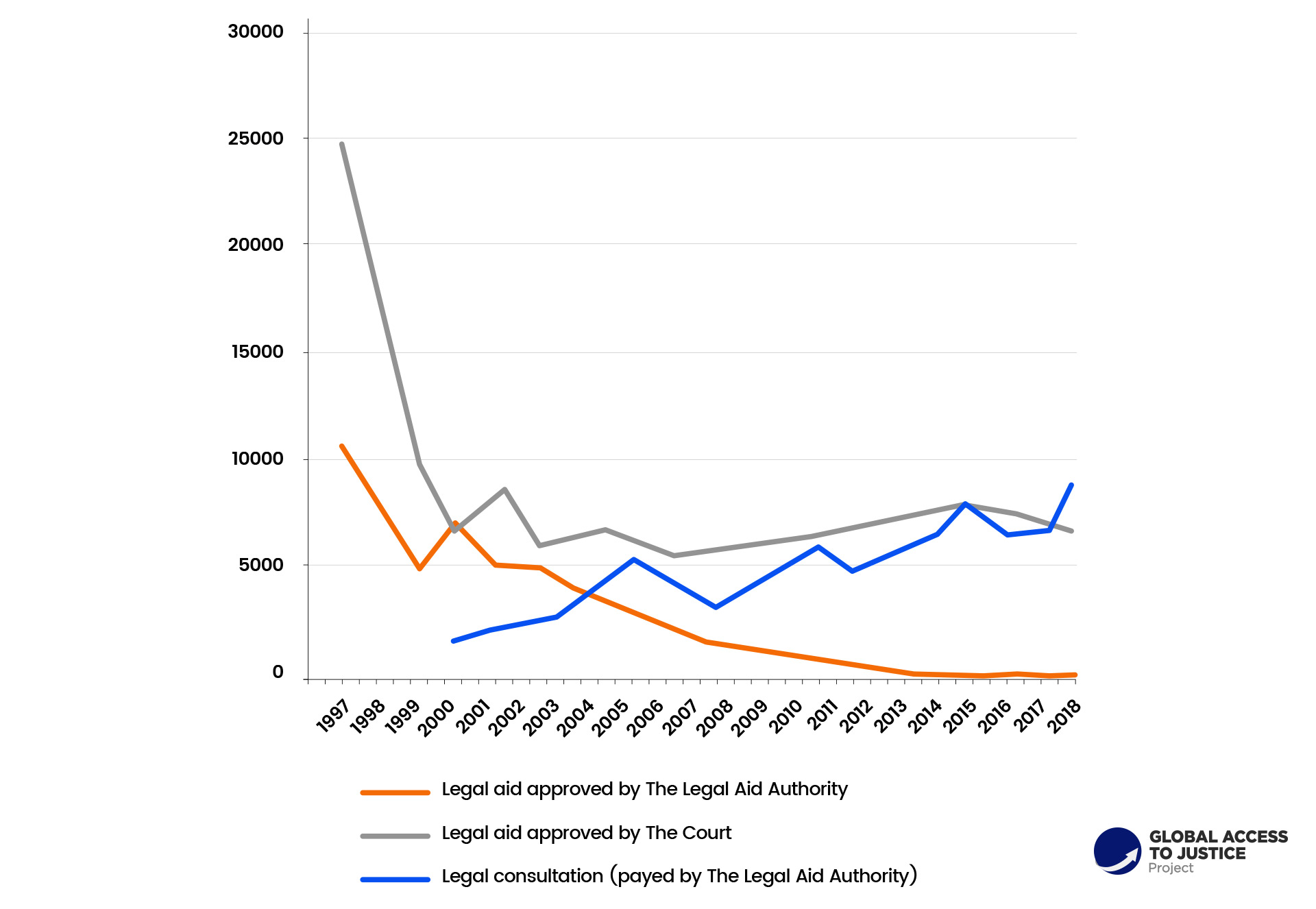

Chart 06 shows the use of legal aid approved by the Legal Aid Authority and the courts (when the case was already before a court) between 1997 and 2018.[55] It also shows the use of legal consultation partly or fully funded by the Legal Aid Authority from 2000 to 2018, since no statistics on legal consultation before 2000 exist. The right to appeal a decision on legal aid is discussed in 5.6.

Chart 06. The number of legal aid matters concluded between 1997 and 2018, approved by either the Legal Aid Authority or by the Courts.

Source: Statistics from the Legal Aid Authority