National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

Republic of North Macedonia[1] (hereinafter referred by its abbreviation RNM) is a landlocked country located in the southeastern region of Europe. RNM is one of the successor states of the former Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia and declare its independence in 1991. Fundamental law of the country is the Constitution[2] adopted in 1991 and its 33 amendments.

RNM is a unitary state and a parliamentary republic. The legislative authority is vested in a unicameral legislature named Assembly (Собрание) composed of 120 representatives elected through a universal suffrage for a term of four years. The Government (Влада), composed of president and ministers, is holder of the executive power. A President (Претседател) elected by a popular vote is a chief of state thought its powers are limited and focused mostly in the areas of international relations and defense. The judicial power is exercised by the courts. A separate and independent Constitutional court is a body that protects the constitutionality and legality. Since the amendments of the Constitution from 2001[3] the form of government also have elements of a consociational[4] democracy where for certain decisions, a majority is necessary by the representatives of the two largest ethnic groups in the country.

The RNM has a population of 2.022.547 inhabitants.[5] Main ethnic groups are the Macedonians with 64.2% from the population and the Albanians with 25.2%. Other ethnic groups include Turks, Romani, Serbs, Bosniaks and Aromanians.[6] Eastern Orthodox Christianity with 64.8% from the population and the Islam with 33.3% are the two predominant religions in the country.[7] The Macedonian and the Albanian languages are official languages[8] however in the units of local self-government other language may also have an official status, on the territory of the municipality.

Since its independence in 1991, Macedonia has made progress in liberalizing its economy and improving its business environment. Its low tax rates and free economic zones have helped to attract foreign investment, which is still low relative to the rest of Europe. Corruption and weak rule of law remain significant problems. Some businesses complain of opaque regulations and unequal enforcement of the law. More than 20% from the population lives below the poverty line.[9]

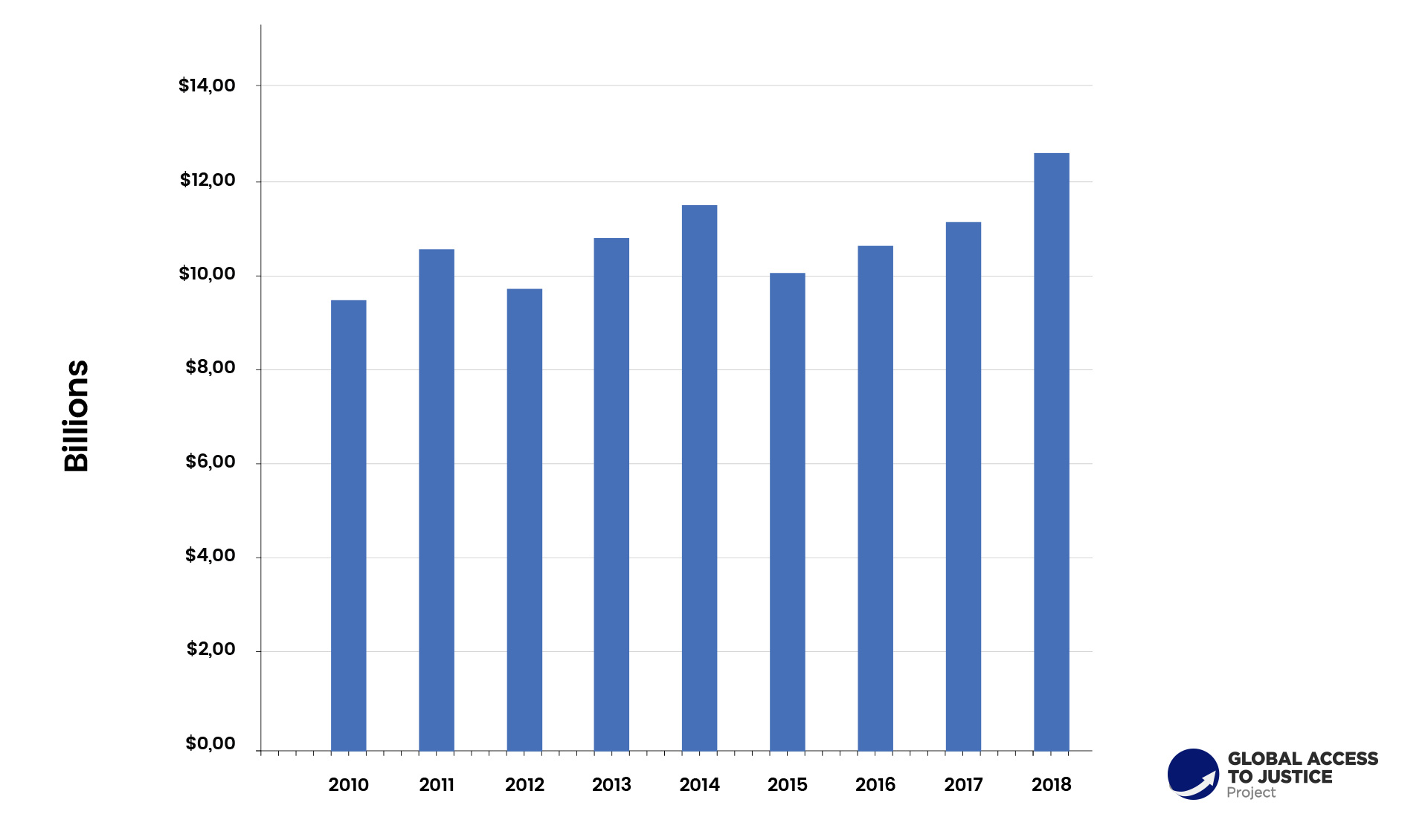

Chart 01. Gross domestic product (GDP) for the last ten years[10]

Chart 02: Republic of North Macedonia and key Human Development Indicators[11]

Chart 02: Republic of North Macedonia and key Human Development Indicators[11]

| Indicator | Value |

| Gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP). | 12.505 $ |

| Inequality index and poverty line (percentage of population deemed to be living in poverty). | 21.5% |

| Life expectancy at birth. | 75.9 |

| Expected years of schooling and mean years of schooling. | 13.3(e) 9.6 (m) |

| Human development index (HDI). | 0.757 |

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of legal system

RNM uses a civil legal system. The law arises primarily from written statutes (закони). The case law is not a source of law and a judicial decision can only be based on the Constitution, the statutes (hereinafter referred as laws) and the international agreements ratified in accordance with the constitution.[1] Judges are not to make law, but merely to interpret it an applied in concrete cases.

2.2. Organization of the justice system

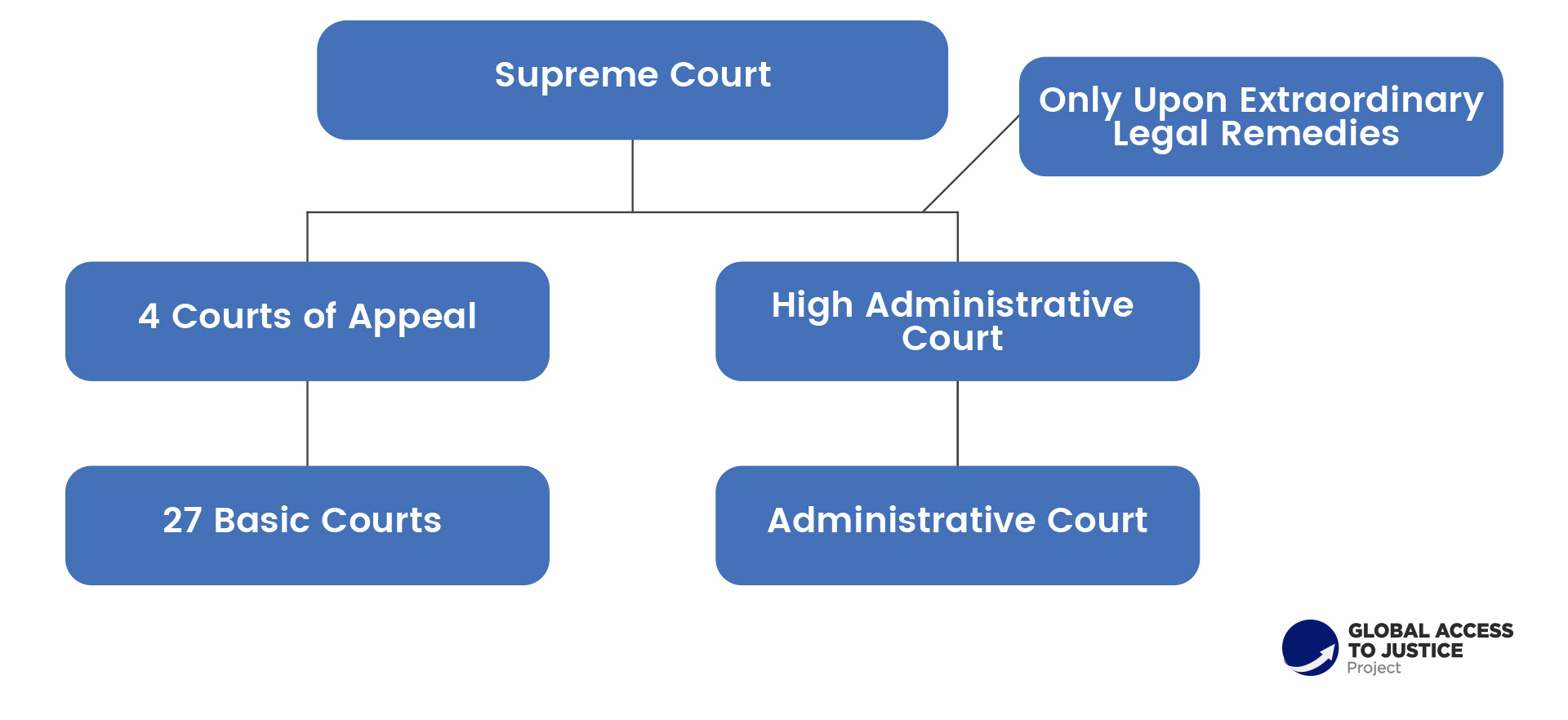

The judicial power is exercised by a unified system of multiple levels of courts. Special courts (ex. Military, ad-hoc tribunals) are explicitly prohibited.[2] The types, competence, establishment, abolishment, organization and composition of the courts, as well as the procedure before the courts, are regulated by a law adopted by a two-thirds majority vote of the total number of representatives. The judicial power within the judicial system is exercised by basic courts, the courts of appeal, the Administrative Court, the Higher Administrative Court, and the Supreme Court.[3]

Basic courts are established for one or several municipalities. They rule in first instance and may be founded as courts with basic (limited) competence and courts with expanded competence.[4] There are 27 basic courts by whom 14 are with basic jurisdiction and 13 with extended. The courts with basic competence are deciding in first instance upon crimes for which the law defined imprisonment sentence up to five year in prison, all misdemeanors ruled in court procedure, civil disputes where the value of the case does not exceed 50.000 EUR as well as family and employment disputes.[5] The courts with expanded competence are deciding in first instance for all cases surpassing the threshold of the courts with basic competence as well as juvenile justice cases, commercial disputes and liquidation and bankruptcy procedures.[6]

The Courts of appeal are established for the territory of several courts of first instance defined by this Law. Their seats are in Skopje, Bitola, Gostivar and Shtip. The courts of appeal are deciding upon appeals against the decisions of the basic courts on their territory as well as upon conflict of competences between the courts of first instance on their territory. They may also have another competences if prescribed by law.[7]

The Supreme Court of the Republic of North Macedonia is the highest court in the Republic that provides uniformity in the application of the laws by the courts. It among other things is competent to decide in third and last instance upon appeals against the decisions of the courts of appeal and upon extraordinary legal remedies against the legally valid decisions of the courts and the decisions of its councils, when determined by law. The Supreme Court of the Republic of Macedonia, at a general session also defines general views and general legal opinions about issues of significance for provision of single application of the laws by the courts.[8]

The Administrative Court exercise the judicial power on the whole territory of the country. It enables judicial review of the decisions of the administrative bodies issued in administrative procedure. The main competence of this court is to decide against individual acts of state administrative bodies, legality of individual acts adopted in the election procedure and disputes arising from a procedure for conclusion of concession agreements, contracts for public procurement of public interest.[9]

The Higher Administrative Court is competent to decide upon appeals against the decisions of the Administrative Court.[10]

Parallel and informal justice structures are not allowed in the country.

Chart 03. Number of processed cases[11] in the first instance courts in 2018[12]

| Court | No. | Court | No. |

| BC Bitola | 25568 | BC Kriva Palanka | 6131 |

| BC Krushevo | 1867 | BC Kumanovo | 40738 |

| BC Ohrid | 19131 | BC Negotino | 6163 |

| BC Prilep | 20762 | BC Skopje I | 111383 |

| BC Resen | 3665 | BC Skopje II | 60804 |

| BC Struga | 17013 | BC Berovo | 4193 |

| BC Gostivar | 41110 | BC Vinica | 4038 |

| BC Debar | 9413 | BC Delchevo | 5455 |

| BC Kichevo | 16406 | BC Kochani | 13706 |

| BC Tetovo | 25051 | BC Radovish | 7516 |

| BC Veles | 18291 | BC St.Nikole | 4980 |

| BC Gevgelija | 9639 | BC Strumica | 22754 |

| BC Kavadarci | 10187 | BC Shtip | 19675 |

| BC Kratovo | 2145 | Administrative court | 36580 |

Chart 04. Organizational chart of the court system of RNM

2.3. The structure of the legal profession

2.3. The structure of the legal profession

The legal profession is practiced solely by a licensed attorneys[13] (адвокати) joined in the Bar association of the RNM. The Constitution establishes the legal profession as an autonomous and independent public service that provides legal assistance and exercises public powers in accordance with the law.[14] As a result of this, the legal profession and its Bar association are enjoying high level of autonomy. The main conditions (among others) for obtaining a license to practice law are university degree in law and passed Bar exam.[15] The legal profession is incompatible with other profession, employment or public function. The profession may be practiced by individual attorneys and law firms. There are not differences in the rights and powers, each attorney have the identical rights and authorizations. Non-lawyer may not be owners of managers of law firms.

2.3.1. Number of licensed practicing attorneys

In 2016 there were 2.503 practicing attorneys[16] in the country. In a mean time this have increased.

2.3.2. Affordability of legal fees

The fees for the attorneys are set in the Tariff[17] adopted by the Bar which is mandatory for all attorneys. The Tariff sets the minimal fees that the attorneys should charge. Invoicing lower fees is prohibited and is considered a disciplinary violation. The current Tariff was adopted in mid-2016 and it increased the fees, for certain action significantly. The increase was justified since the Tariff has not been amended for around 20 years and there have been an increase of the prices in general. The current fees are not affordable for persons living in poverty (over 20 % from the population) while for the other population depending on the type of services.

2.3.3. Legal representation in Court

As a general rule, the representation by a lawyer is not mandatory in the justice system with certain exceptions.

(i) In criminal procedure in the following situations:

- If the accused is dumb, deaf or incapable to defend himself or herself successfully or if a criminal procedure is conducted against him or her for a crime, which, according to the law, entails a sentence of life imprisonment, then the person shall have a defense counsel as of his or her first questioning.

- The defendant shall have a counsel during the detention period, if detention has been imposed against him or her.

- After an indictment has been raised for a crime for which a prison sentence of ten years or a more severe sentence is proscribed in the law, the accused shall have a counsel at the time of the delivery of the indictment.

- The accused shall have a defense counsel during the procedure of negotiation and bargaining with the public prosecutor on the guilty plea.

- The defendant who is being tried in his or her absence shall have a defense counsel assigned immediately after the decision for a trial in absence has been brought.

(ii) In juvenile justice procedure in all situations where the defendant is juvenile.

(iii) In procedures before notaries for:

- solemnization of documents before notaries in the value of the legal issues is over 10.000 EUR unless one of the parties is bank or other financial institution,

- solemnization of contracts for real-estate purchase above 10.000 EUR,

- issuing payment order

- inheritance procedures

(iv) In procedures before enforcement agent for:

- request for forcible enforcement when the value exceeds 10.000 EUR.

- objection against enforcement when the value exceeds 10.000 EUR.

- appeal against the decision upon the objection

The profession paralegal is not legally recognized in RNM. The attorney may be assisted solely by associate attorney or by an apprentice, both with legal education.

2.3.4. Judicial Careers

The Constitution[18] and the Law on Courts[19] explicitly stipulate that the judiciary and the judges are independent and establish certain guarantees for the independence (ex. Election by an independent Judicial Council where the majority of its members are elected directly by the judges; Lifelong tenure; Incompatibility with other functions or professions; etc.). However in practice, the country have faced serious criticism on the lack of independent and impartial judiciary.[20]

The judges and presidents of the courts are elected, assessed and dismissed by the Judicial Council of the Republic of Macedonia[21]. For a judge in a Basic Court the candidate must complete the training in the Academy for Judges and Public Prosecutors. For a judge in Court of Appeals, the candidate must have a continuous length of service as a judge in a basic court, the Administrative or the Higher Administrative Court of at least six years at the moment of signing up for election and to be assessed with a positive mark by the Judicial Council of the Republic of Macedonia. While for the Supreme Court the candidate must have a length of service as a judge in a court of appeal of at least six years. For the Administrative Court a length of service as a judge in a basic court of at least four years is required while for the High Administrative Court six year service in the Administrative court or the Court of Appeals.[22]

In 2018 there were 540 judges in the courts where 60% were female and 40% male.[23] The country has 26 judges on 100.000 inhabitance which is above the European average of 22 judges per 100.000 inhabitance. The judges are elected with no limitation of the duration of the term of office[24] or until their retirement. The retirement age is 64 years for males and 62 for females.

The judge cannot be transferred from one to another court against his/her will.[25] As an exception, the judge of a court of appeal and a basic court may be temporarily, and at the most for a period of one year, transferred to try to another court in the same or lower instance or from one to another specialized division when due to prevention or recusal of a judge or due to significantly increased workload, reduced efficiency or due to the complexity of the cases the day-to-day operation of the court comes into question, but not more than once in a period of five years. In case of temporary transfer, the salary of the judge must not be decreased. Upon expiry of the time for which the judge is transferred to another court or another specialized division, the judge shall be mandatorily returned in the court, that is, specialized division where he/she has previously worked. The temporary transfer of a judge is made by the Judicial Council of the Republic of Macedonia

2.3.5. Prosecutorial Careers

The Public Prosecution Office[26] is a single and autonomous state body prosecuting persons that have committed crimes and other punishable acts determined by a law and performs other activities determined by a law. Its organization is based upon the principles of hierarchy and subordination. The chief public prosecutor of the Republic of North Macedonia is appointed and dismissed by the Assembly for a term of six years with the right to re-election. The public prosecutors are elected by the Council of Public Prosecutors without limitation of the duration of the term of office.[27]

The public prosecutors in the basic public prosecutor are required by the graduates of the Academy for Judges and Prosecutors. Their promotion in the prosecutorial system depends on their length of services in the lower prosecution office.[28]

The public prosecutors (with exemption of the chief public prosecutor of RNM) are appointed for lifelong tenure until the age for retirement (64 for males and 62 for females).

In 2018 there were 191 public prosecutor in the country from whom 66% were female while 43% were males.[29]

2.3.6. Is there a shortage of legal services in RNM?

The results of the existing assessment carried out in the last two years have indicated that with regards to the number of providers of legal services there are no significant problems especially for judges and attorneys which number per 100.000 is in line with the European average. There might me shortage for public prosecutors however the results of the assessment are still not published.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

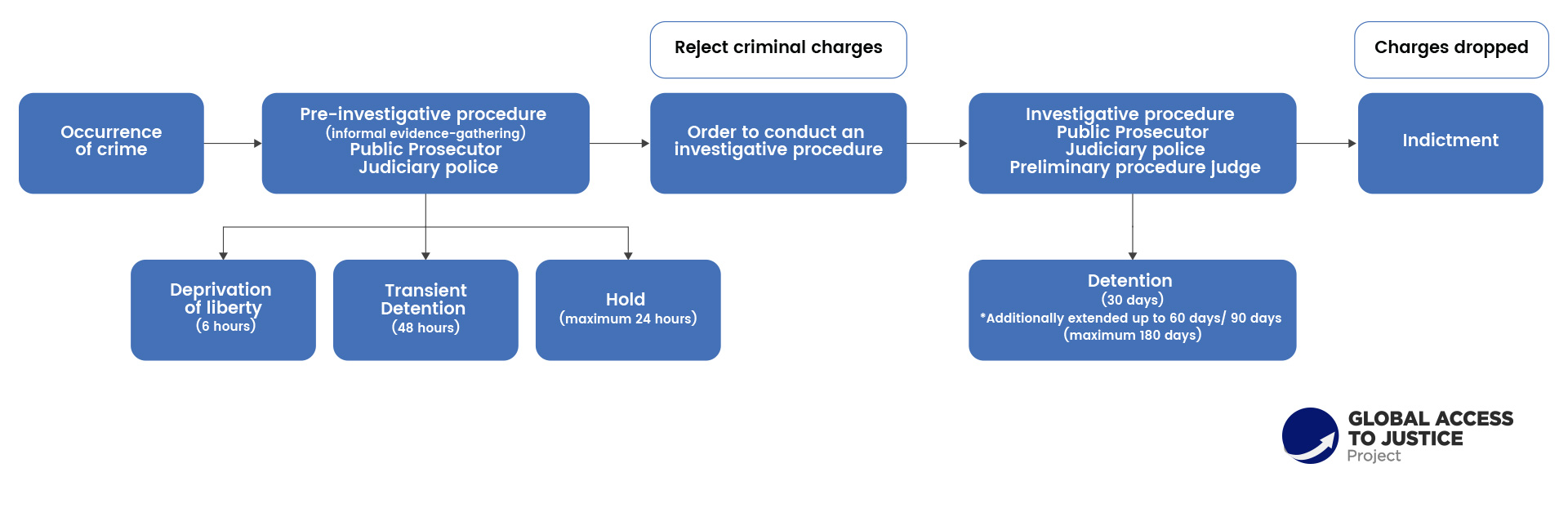

3.1.1. Preliminary Procedure

The criminal procedure[1] starts with the preliminary procedure. The purpose of the preliminary procedure is to gather evidence of the likelihood of the crime and its perpetrator, so that it can then be decided whether to initiate court proceedings or the procedure to be stopped. The preliminary procedure is divided into two parts: pre-investigative procedure and investigative procedure, but despite this formal division of the preliminary procedure, it proceeds continuously as a single phase and thus the evidence gathered in the pre-investigative and investigative procedure has the same probative value, if obtained legally. The preliminary procedure is managed by the public prosecutor, while the judiciary (police) and the prosecution’s investigative centers are in his constant service.

The pre-investigative procedure is an informal evidence-gathering procedure, at a stage when the crime or its offender has not yet been fully disclosed, and is carried out by the police ex officio or at the request of the public prosecutor. The determination of the criminal charges and the pre-investigative procedure are intended to clarify whether the initial suspicion of the offense has been established. The pre-investigative procedure is not regulated in detail, because it is based on police and criminal rules, techniques and methods. No formal decision is taken to start the pre-investigative procedure. The precondition for initiating the pre-investigative procedure is the existence of grounds for suspicion (findings which, based on criminal knowledge and experience, can be assessed as evidence of a criminal offense).

The pre-investigative procedure begins with the filing of a criminal report to the police or other body, with informing the public prosecutor of a criminal offense that is prosecuted ex officio, where police inspections are conducted or the police is acting on instructions from the public prosecutor or when a formal criminal charge has been filed with the public prosecutor, and he cannot decide on it without further gathering of the necessary information. This procedure is conducted with the purpose of providing the public prosecutor with material in order to assess whether, according to the evidence obtained, there are grounds for suspecting that a particular person has committed a crime so that he or she can bring an order against it for conducting an investigative procedure. Otherwise, the public prosecutor will dismiss the criminal charges.

The police do not have to wait for special orders from the public prosecutor, but is obliged following the receipt of the criminal charges or after learning of a crime that is being prosecuted ex-officio, to take all necessary measures to find the perpetrator of the crime, to prevent the perpetrator or an accomplice to hide or flee, to discover and preserve any traces of the crime and objects that might be used as evidence, as well as to collect all possible accounts that might be useful for a successful criminal procedure. It is important to emphasize that the public prosecutor has the right and duty of constant control over the police in carrying out these action and that he can implement these measures himself.

Based on the results of the pre-investigative procedure, the public prosecutor decides whether to waive prosecution, reject the criminal charges or to enact an order to conduct an investigation procedure. The deadline for making a decision on the criminal charges is three months from the day of receipt of the report. All activities and actions taken by the authorities during the preliminary procedure are secret, as the principle of presumption of innocence must be respected.

The investigative procedure is the second phase and is conducted by the public prosecutor. The investigation conducted by the public prosecutor is complex, his powers are great, but his obligations and responsibilities are also great because he is obliged to conduct the investigation fully and in all respects, with his role being to gather all the evidence, and those who favor him and those who favor the defendant.

The pre-trial judge is the other entity in the investigative procedure. His role is during the pre-trial procedure to decide on the freedoms and rights of the accused and other matters specified by law.

The investigative procedure must commence with the issuance of an order to conduct an investigative procedure. The order is issued by the public prosecutor, when he/she considers that there is a reasonable suspicion that the suspect has committed an ex officio crime, in which the public prosecutor enters the following elements: personal data about the suspect, description of the act for which the order is issued and legal qualification of the same. In the order for conducting investigation, the public prosecutor will determine what should be undertaken during the investigation, which investigative actions should be taken, which particular issues should be investigated, and which particular circumstances need to be investigated. Before issuing an order for investigation, the public prosecutor may examine the person against whom the investigation is requested.

Once the order is issued, the statutory 6-month deadline for completion of the investigation begins, with the option in complex cases, the higher public prosecutor to extend this deadline for another six months, and exceptionally, this deadline may be extended by the Public Prosecutor of the Republic of Macedonia for another three months, while in the case of case of organized crime by the public prosecutor of RM, this deadline can be extended for another six months.

The public prosecutor concludes the investigation when he finds that the state of affairs is sufficiently clear to be able to bring charges or to halt the investigation. The decision needs to be made within a period of 15 days (30 days for criminal offenses that fall within the category of organized crime) from the completion of the investigation procedure and the expiry of the statutory deadlines mentioned above. The public prosecutor shall be obliged to deliver a notification of completion of the investigation procedure to the suspect and his or her counsel.

During the preliminary procedure there are two situations of deprivation of liberty without a court order – deprivation of liberty by anyone and deprivation of liberty by the judicial police. A person caught while committing a criminal offense may be deprived of his liberty if there is a danger of fleeing and the police are immediately notified. The person deprived of liberty shall be kept until the arrival of the police, who must be informed immediately. Without a court warrant, the judicial police may also arrest a person if there are grounds for suspicion that he or she committed a crime that is prosecuted ex-officio, only if there is a danger of procrastination and if some of the conditions for detention are met, but it is obliged immediately, and not later than 6 hours from the deprivation of liberty, to take the person before a competent judge of the preliminary procedure, and inform the public prosecutor thereof.

As an exception, the judicial police may hold the person who has been arrested, if it is necessary to hold the person for the purpose of establishing his or her identity, checking up an alibi or it is necessary, due to other reasons, to collect additional information that would be essential for the criminal procedure against that person. The arrested person who has been held, shall be brought before the custody officer at the specially designated police stations, within a period of 6 hours, who shall decide, with a separate written and elaborated decision, whether the person will be held or released. Any delay in the procedure shall be separately explained. A person may be held for 24 hours at most, from the moment of the arrest, and within this time period, the person has to be brought before a competent judge. After the expiry of this time period, the person who has been held shall be released.

After the enactment of the order to conduct an investigation procedure, the public prosecutor may put forward, to the preliminary procedure judge, an elaborated motion for detention or other measures to ensure the presence of the defendant. The preliminary procedure judge shall be obliged, without any delays, to consider such a motion and rule on it immediately.

Detention can only be determined throughout of the investigative procedure ie after the order for investigation procedure has been issued by the public prosecutor. The detention can be imposed, if there is a reasonable suspicion that a certain person committed a crime, and if detention is required for an unobstructed criminal procedure to take place:

- if the person is hiding, if his or her identity cannot be established, or if there are other circumstances that would indicate that the person might flee;

- if there is a reasonable fear that the person will hide, manipulate or destroy any traces of the criminal offense, or if there are special circumstances that would indicate that he or she shall impede the criminal procedure by influencing witnesses, expert witnesses, accomplices or other persons who have been covering up the crime;

- if special circumstances justify the fear that he or she might repeat the crime, or complete the attempted crime or commit the crime that he or she has been threatening with; or

- if the defendant who has been properly summoned obviously tries to avoid appearing during the main hearing, or if the court has tried on two occasions to properly serve the defendant, whilst all the circumstances show that the defendant is obviously avoiding receiving the summon

Detention during the preliminary procedure may be imposed by the court, upon a written and elaborated proposal by an authorized plaintiff, and only on the grounds listed in the proposal by the authorized plaintiff.

The detention may last not more than 30 days from the moment when the person was arrested. Any deprivation of liberty shall be computed within the overall duration of the detention. Upon an elaborated motion by the public prosecutor, the Court Chamber, may additionally extend the detention during the investigation for another 60 days (90 days for a crime that entails a prison sentence of at least four years) at most.

Upon proposal from the public prosecutor, with a written and elaborated decision, the preliminary procedure judge may impose transient detention to the arrested person, up to 48 hours from the moment when the arrested person appeared before the preliminary procedure judge, if he or she believes that there is a grounded suspicion that the person committed the crime that he or she is accused of and that the conditions for detention have been met, if the public prosecutor has not yet issued an order for investigation against that person.

The total duration of detention during the investigation, also counting the time while the person was deprived of liberty before the enactment of the detention decision, shall not exceed 180 days, and immediately after the expiry of that period the defendant shall be released immediately.

Chart 05. Organizational chart of the investigation procedure

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

After the completion of the investigation procedure, when the public prosecutor establishes that there is enough evidence to expect a conviction, he or she submits an indictment to the competent court. In addition to the indictment, the public prosecutor submits the material evidence, minutes and recordings of the examination of persons and encloses a list of evidence which proposes to be presented at the main hearing.

After the receipt of the indictment the court does compulsory judicial control of it. Competent authority for evaluation of the indictment is the judge for evaluation of the indictment (individual judge) for a criminal offense punishable by up to ten years in prison or indictment evaluation chamber (three-judge panel) for a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment of ten years or more.

The judge or the indictment review chamber shall deliver the indictment to the defendant who is free without delay and, if detained within 24 hours of receipt of the indictment. Upon receipt of the indictment, the defendant may file an objection against the indictment within 8 days of receipt, submit a statement of guilty plea or submit a list of evidence which he or she proposes to be presented at the main hearing.

After the indictment entered into force, on the day the decision to approve it was entered, that is, by inserting the clause for approval of the indictment, together with the decision to approve it, the material evidence submitted and the list of evidence which the parties propose to be performed, shall be submitted to the competent court.

After the indictment has been approved and prior to the completion of the main hearing, upon proposal by the parties, detention may be established, extended or revoked only with a decision by the Trial Chamber (Article 25, paragraph 5 of the Law on Criminal Procedure). After the indictment has entered into effect, the detention shall last for no more than: one year for crimes that entail a prison sentence of up to 15 years and two years for crimes that carry a life-time prison sentence. Upon proposal by the parties and ex-officio, following the expiry of thirty days after the last detention decision has entered into effect, the Chamber shall be obliged to inspect whether the reasons for detention still exist and enact a decision for extension or revocation of the detention.

When the verdict of the court includes a prison sentence for the defendant, the Trial Chamber may order for the person to be detained, if he or she is not in detention already. The Trial Chamber that leads the main hearing shall be competent to rule on any detention or revocation of detention, from the completion of the main hearing to the proclamation of the judgment, and the Chamber referred to in Article 25, paragraph 5 shall be competent from the moment of proclamation of the judgment, until it enters into full effect. The detention in this phase may last until the person starts serving the sentence, i.e. until the verdict enters into full effect, but not longer than the duration of the prison sentence.

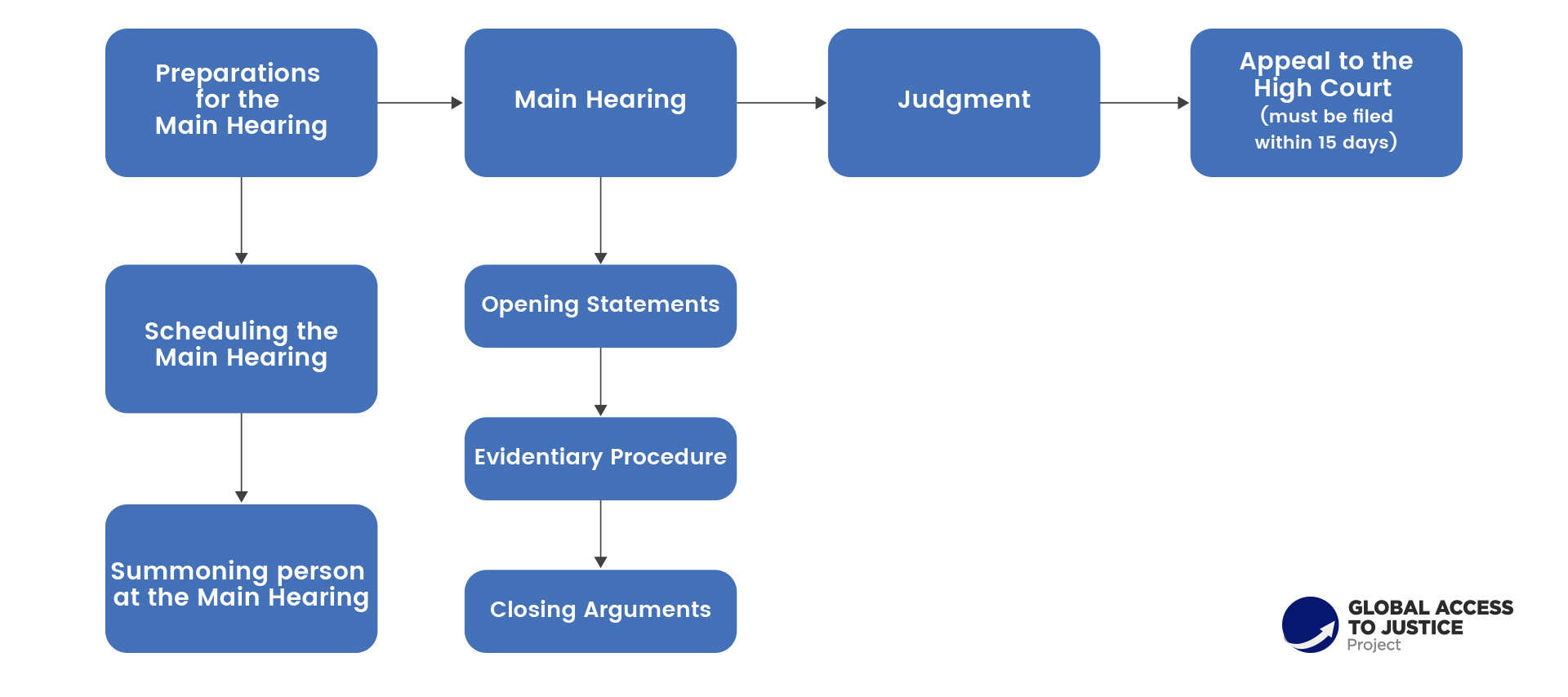

Once the indictment is received and checked, the competent court schedules a main hearing. The main hearing is a central, main part of the criminal proceedings, in which the accusatorial of the procedure and the principle of equality of arms are most prominently displayed. The Main hearing starts with the opening statements of the parties. The parties in their opening statements present their theory of the case, as well as the evidence on which they base it. After the opening statements, the evidentiary procedure is open, where the parties present the evidence they have proposed. With The closing arguments, the main hearing is concluded. The closing arguments represent the last address of the parties where they give their views on what came out of the evidence presented and draw their own conclusions about the proving or unproven of the decisive facts. After the main hearing has been concluded, the Chamber will resume counseling and voting for a judgment.

There is no legal deadline/time limit for completing the criminal prosecution proceedings. However Basic Concepts section in the Criminal Procedure Law there is a provision about the right to trial within a reasonable time. According to the provision any person that is subject of the procedure shall have the right to be taken before a court within a reasonable time and tried without any unjustified delays. The court shall be obliged to conduct the proceedings without any delay and to preclude any abuse of the rights that belong to the persons that participate in the proceedings.

The legal system of N. Macedonia allows criminal judgment in absentia, but under prescribed conditions. The defendant may be tried in his or her absence only if he or she has fled or is otherwise inaccessible to the state institutions, in the event when there are especially important reasons for the person to be tried, although he or she is absent. Upon a motion by the plaintiff, the Trial Chamber shall enact a decision to try the defendant in his or hers absence. Any appeal shall not prevent the enforcement of the decision. The defendant on trial in absentia must have a defense counsel appointed immediately after the decision for trial in absentia is made.

There is an option for repetition of the procedure for a person convicted in absence. Any criminal procedure whereby a person was convicted in absence (Article 365 of this Law) and there is a possibility for the person to be tried in his or her presence shall be repeated, if the defendant or his or her counsel puts a motion for repetition of the criminal procedure within one year as of the day when the convicted person learned of the conviction in his or her absence.

Chart 06. Organizational chart of the main hearing phase of a criminal procedure

3.1.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

3.1.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

The most common complaints regarding the criminal procedure, before the European Court of Human Rights against RNM are the violations of Article 3 of the Convention (prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment) and Article 6 (the right to a fair trial), in particular a trial within a reasonable time, a violation of the right to defense, the right to equality of arms, etc.

In the Analysis of the data collected from the court criminal proceedings monitored issued by OSCE and All For Fair Trial Coalition[2] among the conclusions where the following:

- Often cases of absent defense attorneys in hearings when a detention measure was or was being applied against defendants which is greatly undermining the right to effective defense of the accused person

- Increasing trend in cases where the court examines the defendant, in the capacity of a self-proposed witness, in absence of a defense attorney.

- The upward trend in unequal treatment of the public prosecutor and the defense by the court is worrisome

- Decrease in the number of guilty pleas in the main hearings in all observed courts. A correlation is observed between the severity of criminal act, the low penal policy of judges upon the completion of main hearings, the severity and uncertainty of sanctions in conditions of guilty pleas, as well as the role of the court and the role of the defence attorney in the process of assessing the guilty pleas as negative factors for application of this procedure that is intended to accelerate the main hearing.

- an increase in the number of complaints raised by defence attorneys in relation to their access to evidence.

Statistics and analyses show that the police have factual monopoly over investigations, and are key factor in the criminal justice system, especially in establishing whether and who is responsible for criminal offences. Large majority of perpetrators have never been discovered, while almost all reported or known perpetrators are later charged and convicted.

Inferior status of the public prosecution and the courts within the criminal justice system, including their failure to properly protect lawfulness and legality, as well as rights and freedoms of defendants, brings under question their legitimacy, which is mainly due to their insufficient human and institutional capacity, but also serious problems in terms of autonomy and independence from the executive branch of government

Establishment of investigation departments at the pubic prosecution is an important requirement with a view to speed investigations, overcome the police’s monopoly over investigations and address hierarchical dualism of the criminal police. Judges deciding on legality and lawfulness of arrests and other actions or measures taken against suspects must hear in them in person, including all people involved in alleged police ill-treatment, and must gather all relevant evidence.

Having in mind the fact that the police and the public prosecution have resources and are competent to conduct investigations and gather evidence, it is of critical importance for the defence to be given insight in evidence they have collected, both in terms of timing and scope of insight granted. Trial in absence should be reduced to exception. In that regard, courts should insist on locating persons who are allegedly unavailable to be tried, requesting the competent authorities to make their best effort, whereas the law or court practice should provide clear definition of actually important reasons for allowing trial in absence.

3.2. Civil Procedure

3.2.1. Overview of civil procedures

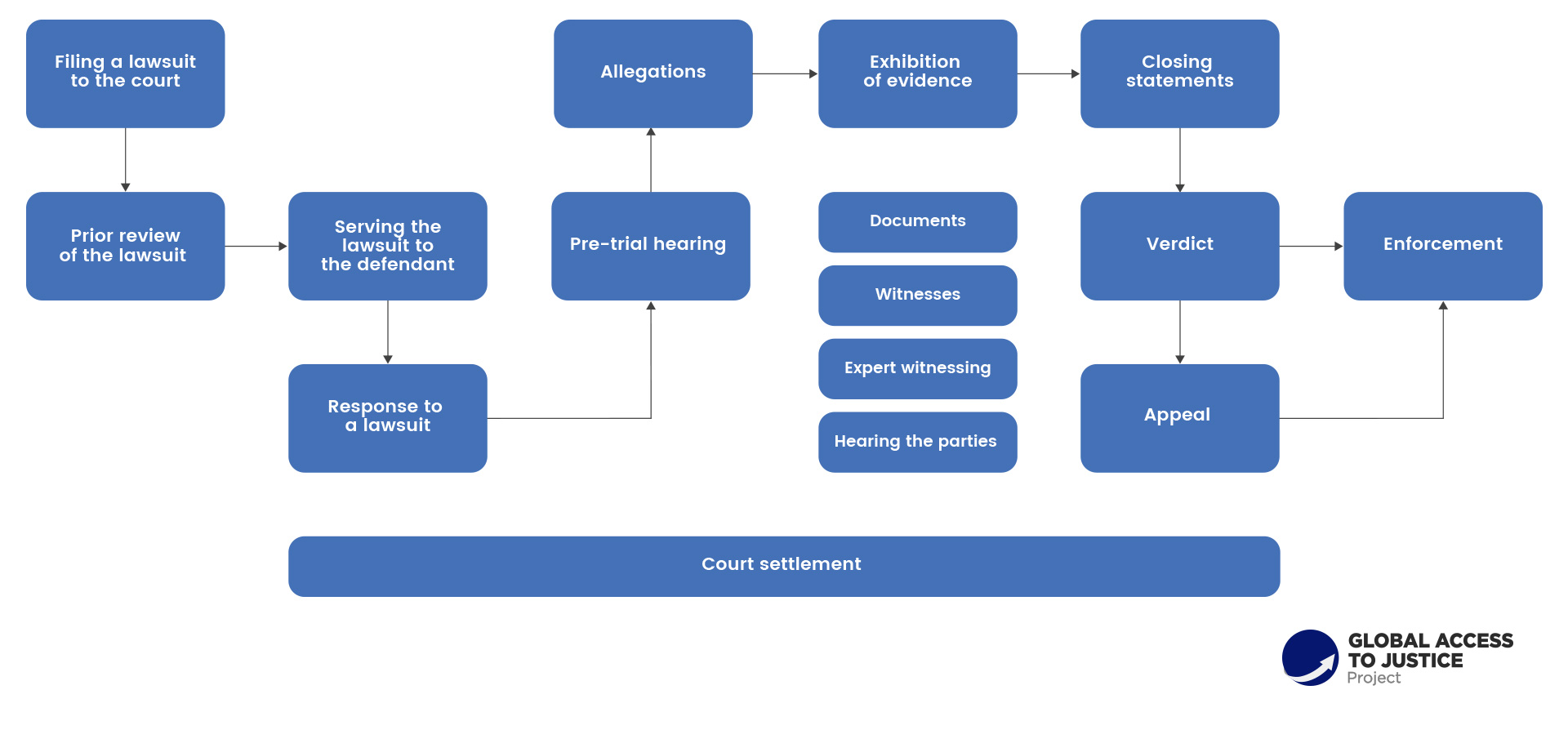

The non-criminal cases, depending by their nature, may be processed in civil or in administrative procedure. Since the civil procedure is the main alley for resolving disputes it will be in the focus on further elaboration. It is mainly a court procedure though certain competencies are delegated to a public notaries (ex. payment orders, inheritance procedures) while the enforcement is devolved to a private enforcement agents. The administrative procedure is the procedure by which individuals and entities are realizing their rights before administrative bodies (ex. social welfare rights, pension and disability etc).[3] It is regulated by the Law on General Administrative Procedure though for specific procedures, special procedural provisions may be envisioned. In this cases, the general law has subsidiary application for the issues not covered by the special provisions.[4]

The civil procedure incorporate litigation and non-contentious procedure as well as rules regulating the enforcement. Its main component, the litigation procedure (парнична постапка) encompasses rules on the basis of which the court contends and decides in the disputes for basic human and citizen’s rights and obligations, for personal and family relations of the citizens, such as the labor, trade, property and other civil disputes[5]. The litigation procedure may be general or special. Special litigation procedures includes: labor relations disputes, hindering of possession, payment order, small claims disputes, procedures in selected courts and trade disputes.

The Law on Litigation Procedure establishes several special procedures where the time limits for processing the cases are shortened due to the nature of the cases, the urgency required as well as the need for efficiency. Such procedures are: labor relations disputes, hindering of possession procedures, payment order, and small claims disputes.[6] If the claim is related to one of these issues, the court automatically process the case in these fast lane procedures.

Specific urgent procedure is established for securing claims[7] while the main issue and the merits of the case are contended in a litigation or it is in an enforcement procedure. The court is obliged to take on the case within three days as of the day of receiving the request at the latest. The procedure for securing claims is initiated upon a request of the plaintiff, i.e. the creditor. The instruments for securing claims[8] shall be:

- right to pledge on immovables and movables in cases where enforcement document is issues and the enforcement is pending

- previous measures in cases where there is a monetary claim and a procedure has been initiated but it has not become legally valid or enforceable, if the creditor renders the danger probable or if there is an assumed danger that without such securing the effectuation of the claim would be thwarted or significantly hindered.

- temporary measures in cases were the procedure has not been initiated and the creditor renders probable the existence of the claim and the danger arising from the absence of such measure that the debtor is to thwart or significantly hinder the collection of the claim, by alienating, covering or in any other way using his/her property, i.e. his/her funds.

- transfer of ownership of objects and transfer of rights if there is will among the creditor and the debtor to reach a settlement.

The attempt to use alternative dispute resolution before initiating litigation procedure is solely obligatory for the commercial disputes[9]. If the commercial dispute is for a monetary claim where the value of which does not exceed 1.000.000 MKD (cir. 18.100 $) the parties are obliged, before filing the lawsuit, to try to resolve the dispute by mediation. When filing the lawsuit, the plaintiff is obliged to attach a written proof issued by a mediator that the attempt for resolving the dispute by mediation has not succeeded. The lawsuit which does not contain the proof shall be rejected by the court.[10]

The litigation procedure, as established with the Law from 2005, is based upon the principles of adversarial system with certain limited elements from the inquisitorial system.[11] The judge is responsible for formal management of the procedure (scheduling hearings, deciding upon motions etc) however its role in pursuing evidence is limited. There is only one exemption from the adversarial principles is the possibility of the judge ex officio to determine the facts. The court is authorized to confirm the facts not being stated by the parties, and to exhibit the evidence not being proposed by the parties, if the outcome of the contention and the substantiation results in the parties being headed towards disposing with claims they cannot dispose with. However it cannot base its decision on facts and evidence wherefore the parties have not been granted the possibility to declare themselves.[12]

Chart 07: Organizational chart of the 1st instance litigation procedure

3.2.2. Encouraging settlement

3.2.2. Encouraging settlement

The Law on Litigation Procedure envisions two main instruments that the Court may use to encourage the parties to reach a conciliation, to inform and refer the parties to resolve the dispute via mediation and to facilitate reaching a court settlement.

The court during the preparation of the pre-trial hearing is obliged, in the disputes where mediation is allowed, to serve to the parties written instructions, together with the summons for the pre-trial hearing, stating that the dispute can be resolved in a mediation procedure and to request from the parties to state whether they agree to resolve the dispute in a mediation procedure.[13] If the parties agree the dispute to be resolved in a mediation procedure, the court shall adopt a decision to terminate the procedure.

The court, during the whole course of the procedure, shall point the parties to the possibility for court settlement and can help them conclude a settlement. The settlement agreement of the parties shall be inserted in the minutes and it shall be deemed concluded when the parties sign the minutes after the minutes on settlement is read to them.[14]

Unfortunately, data on the effectiveness of these instruments is not available since no studies have been carried out targeting this issue.

3.2.3. Consistency with the Rule of Law

The comprehensive reform of the civil law system started in 2011 with the initiation of a codification of the civil law in order to improve the quality of civil law regulation, as well as to overcome the legal gaps currently faced by legal practitioners in the application of civil legal norms. Key challenge was the efficiency and the lengthiness of civil procedures. The Law on Litigation Procedure has contributed to significantly shorten the length of the proceedings and reduce the huge workload of the courts by exempting them from handling payment orders and inheritance proceedings which had burdened the judicial system for many years. However, the practical application of some of the new provisions, especially those related to cross-examination, compulsory expertise upon filing a lawsuit, etc. indicates the need to review these provisions by organising public discussions.

European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in several cases has found violations of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) on the right to a fair trial, respect for family life and protection of property. Also efforts are needed to promote the use of alternative dispute resolution. Arbitration is still not considered as a viable tool to ensure justice, either by parties or by the courts. The effects of the implementation of the new law on mediation, adopted in 2013 are still to be assessed.

Overall, the system has proved to be an improvement compared to the previous system of enforcement by the courts. The notary payment order works well, discharging the burden on the courts. However, the overall cost of enforcement and the length of the procedure still obstruct the system’s efficiency. This, together with the mandatory presence of an attorney for procedures before notaries (including for inheritance) risks impeding access to justice. The monitoring of the enforcement officers’ activities by the Chamber and the Ministry of Justice needs to be improved. Regarding property rights, the absence of strategic documents results in lengthy procedures and insufficient coordination between institutions. This leads to delays in updating registers by the municipal authorities and the Central Register.[15]

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

3.3.1. The compulsory diversion of disputes

Compulsory diversion of dispute to resolution mechanisms outside the formal judiciary is only present among the commercial disputes where the value of the claim is below 1.000.000 MKD. In these cases the parties are obliged, before filing the lawsuit, to try to resolve the dispute by mediation. When filing the lawsuit, the plaintiff is obliged to attach a written proof issued by a mediator that the attempt for resolving the dispute by mediation has not succeeded. The lawsuit which does not contain the proof shall be rejected by the court. The mediation is performed by a private licensed mediators in line with the Law on Mediation.[16] The costs for the mediation should be covered by the parties.

3.3.2. The voluntary or consensual diversion of disputes

Consensual diversion of dispute is available for different types of cases. There are several mechanisms established by law which provide forums for ADR. Those mechanisms are:

- arbitrage, for trade and commercial disputes

- mediation, in property, family, labor, trade, consumer, insurance disputes, disputes in the field of education, environmental protection, disputes related to discrimination

- specific mechanisms for peaceful resolution of consumer disputes

- peaceful resolution of employment disputes

These mechanisms are not government sponsored. The decision/outcome of these mechanisms must be in appropriate form established with law in order to have a legal effect. However all these mechanisms are underused and there is low awareness among the population for the benefits of their uses.

3.3.3. ADR Policy Drivers

One of the main drivers in the reforms in the legal system in the country is the EU integration and the need to meet the EU standards in different aspects of the society. Such is the situations with the ADR processes. The EU encourage and support development of efficient ADR processes in the country however still there is insufficient trust among the representatives of the conventional legal professions on the efficiency of these mechanism combined with general unpreparedness of the population to delegate their dispute to resolution to a private individual/entity. The costs and duration of court procedures are still more acceptable solution than to attempt to solve the issue by ADR. There is need of greater awareness raising and simultaneous improvement of the legislative framework on ADR based upon through assessment and evidence.

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

The reforms that were implemented in the past 15 years in RNM aimed at reducing the costs and time when deciding in civil cases through amending the procedural law, not substantive. The premise was that by speeding up and simplifying procedures, not substantive laws, will be sufficient to increase the efficiency of the judiciary. For example, the amends to the Law on Litigation Procedure from 2011 prescribed strict rules on the content of the motions and any failure to meet this rules shall result with dismissal of the lawsuit. One specific area which also was reformed was the payment orders for debts, mostly for utilities. The deciding upon these payment orders was delegated to the notaries with the expectation that it will remove some burden from the courts. However all these reforms were related to the rules of procedure.

The legal system in RNM does not allow use of equity when deciding in disputes. Each decision must be based upon a statute.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

4.1. Statutory commitment to access to justice, equal access to court and fair trial

The Constitution of RNM does not recognize explicitly the right for access to justice though it establishes certain principle related to the fair trial rights such as: the presumption of innocence, the prohibition of double jeopardy and nullum crimen sine lege. The main legal source on access to justice and the fair trial is Article 6 from the European Convention on Human Rights. The Convention was ratified in 1997 and since than is part of the national legal system, hierarchically above the laws enacted by the Assembly. This article determines the key criteria defining the rights to fair trial as well as the right to access to a court as one of its elements. The Convention is directly applicable in national context while the case law of the European Court on Human Rights provide guidance on its proper interpretation.

4.2. Political commitment to access to justice

In 2018 the Government adopted the Strategy for Reforms of the Judiciary[1] for the period 2018 – 2019. One of the key strategic goals of the judicial reforms is the access to justice. Within the framework of the Strategy, a new Law on Free Legal Aid was adopted. In a video message on the starting date of its implementation, the Minister of Justice, Ms. Renata Deskoska PhD stated “this law contributes in building the rule of law however it also have one humane dimension which is that the financial status should be burden in realization of the rights of the citizens”[2]. In general there is positive attitude among the political elites however since the country faces very serious problems related to the independence of judiciary and fighting corruption and organized crime, the access to justice is not considered as a priority issues and as a result of that is not very much present in the public debate.

4.3. Responsibility for access to justice policy

The responsibility for access to justice policy lies within the hands of the Ministry of Justice.

4.4. Government access to justice policy

The access to justice policy is stated in the above quoted Strategy for reforms of the judiciary. It includes a national legal aid system, increase legal awareness, involvement of NGO and legal clinics, increased state budget on legal aid as well as reforms in the legislation concerning attorneys, notaries, enforcement agents and mediators.

4.5. Equal access to justice for minorities, immigrants, indigenous peoples or other groups

The Roma minority is facing serious obstacles in realizing access to justice. Facing poverty, social exclusion and prejudices, this minority group is disproportionally affected by the lack of access to justice and legal remedies. There are few areas in which this problem is most concerning. The first is the problem of unregistered individuals[3] (people who are not enlisted in the birth registries) which results with lack of any legal identity, access to education, healthcare and social services. This problem is overwhelmingly affecting the Roma population. The rigid framework on birth registration combined with lack of effective policies are preventing in resolution of this problem. The Roma population also faces problems from legal nature related to proper housing, discrimination, and healthcare.

With regards to migrants, through North Macedonia as a transit country a significant number of migrants are transiting to their destination in Western Europe. They are often victims of migrant smuggling and trafficking and may be detained for almost six month while in the same time do not have the right to a legal aid.

4.6. Access to justice subject of public or scholarly debates

The improvement of the access to justice is one of the key priorities of a significant number of NGOs active in the country. They, as both service providers and advocating for the rights of certain specific vulnerable groups (ex. Roma community, LGBT population, victims of domestic violence and human trafficking, homeless persons, people living in extreme poverty, sex workers, intravenous drug users etc.) have identified that these group among other problems, face serious obstacles in accessing justice. As a result of this, main initiatives on reforming access to justices as well as assessments and policy documents came from the NGO sector. Since 2011, a group of authorized providers of preliminary legal aid[4], supported by the Foundation Open Society Macedonia have prepared and issued annual reports[5] on the implementation of the Law on Free Legal Aid. The Foundation pursued significant effort in legal empowerment activities.[6] Beside the legal aid, numerous documents were prepared and events organized related to the access to justice issues faced by specific vulnerable categories.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

Republic of North Macedonia as one of the constituent republics of the Yugoslav federation was part of the federal legal system established following WWII. The right to legal aid in both, criminal and civil procedure, in the form of court appointed attorney paid by the budget for indigent parties, was recognized on federal level in the 1950s. The Criminal Procedure Code from 1953[1] prescribed that the court may, upon request by the defendant, to appoint defense counsel, if the procedure is tried in front of district court (more serious crimes), and if the defendant due to his/her financial situation is not able to afford an attorney. The request may be submitted only after the indictment.[2] With regards to the civil procedure, the Law on Litigation Procedure from 1957[3] established the possibility for court appointment of an attorney, upon request by an indigent party which was exempted from payment of procedural costs.[4] Though in the following decades these laws were amended several times, the provisions regulating legal aid remained relatively unchanged.

In the 1990s and 2000s several processes required reform of the legal aid system in the country. Following the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Macedonia proclaimed its independence in 1991 and started a process of transition from one party planned economy, to a multiparty parliamentary democracy with market economy. These processes combined with unfavorable international situations (war in the region etc.) resulted with swift decrease in the living standards and high rates of unemployment and poverty, increased rate of organized crime and corruption and week institutions. In the same time, the country determined its strategic aspiration for membership in the Council of Europe, NATO and EU. In order to fulfill this, the country was required to accept and implement international and European standards on human rights and rule of law which also included acceptance on the standards for access to justice. The country ratified several international agreements requiring reforms in this area, from whom the most important is the European Convention on Human Rights ratified in 1997. Simultaneously, the country’s civil society was strengthened with support of international donors and these organization strived to close the gap of the lack of provision of appropriate services to vulnerable groups including legal support.

The first main reform of the national legal aid system occurred in 2009 with the adoption of the first Law on Free Legal Aid[5]. The law established a state funded legal aid system for civil and administrative issues, administered by the Ministry of Justice. The legal aid included legal aid in procedures provided by attorneys, and preliminary legal aid (information and advices) provided by authorized NGOs and regional offices of the Ministry of Justice. It established a supplementary system of legal aid to the already existing systems established with the laws regulating court procedures especially the litigation procedure. Nonetheless that the civil society required adoption of this law, the key reason that prompted the adoption of this law were the weaknesses[6] identified by the European Commission that needed to be properly addressed in order for the country to move forward to the EU integration.

As a result of the limited involvement of all relevant stakeholders during the process of the drafting of the law, its implementation faces significant challenges that significantly restricted the access to justice, instead providing it. The eligibility criteria about applicant income and assets as well as the legal issues were quite restrictive, the procedure for obtaining was very long (with median value around 2 months), there was low public awareness, the court fees and fees for expert witnesses were not covered.[7] As a result of this, the number of individual that benefited from legal aid was very small. In order to address the identified problems, a new reform process was initiated in 2015 and accelerated in 2017[8], now with active involvement of the civil society, which resulted with a new Law on Free Legal Aid, adopted in May 2019.

The reforms in the area of human rights and rule of law, including the access to justice, in the country are largely related to, and driven by the process of integration into the European Union. Since this process also strongly require further development of the democracy it may be concluded that the reforms in the area of access to justice correlated to the overall development of the democratic processes.

In the current circumstances, where other mechanisms for improvement of access to justice are not promoted and developed, the legal aid remains a key instrument in facilitating access to justice in the country.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

The Constitution of Republic of North Macedonia does not stipulate explicitly the right to legal aid. It specifies that the individuals have the right to an attorney in the police and court procedure[9] and that the attorneys provide legal assistance[10]. However it does not containing any provisions on providing free of charge legal assistance to indigent parties.

The statutory framework for legal aid, depending on the legal issues for which legal aid is provided can be grouped in three main groups:

(i) Legal aid in criminal procedures

(ii) Legal aid in civil and administrative procedures

(iii) Legal aid in juvenile justice

5.2.1. Legal aid in criminal procedures

Main provisions regulating legal aid for defendants in criminal procedures are set in the Law on Criminal Procedure. Article 74 regulates the compulsory defense with a defense counsel and ex-officio defense counsel (Задолжителна одбрана со бранител и бранител по службена должност). It regulates the situations in which defense counsel is compulsory and if the defendant does not have counsel it will be appointed to him/her. On the other hand, Article 75 regulates the defense of indigent parties (Одбрана за сиромашни). It enables possibility for a defendant without the means to have a defense counsel upon fulfillment of certain criteria. The legal aid for victims of crimes is covered by article 49 from the Law on Free Legal Aid.

5.2.2. Legal aid in civil and administrative procedures

The legal aid in this area is mostly covered by the Law on Free Legal Aid described in detail bellow. However there is one provision in the Law on Litigation Procedure (Article 165 paragraph 1) in the section where exemption of procedural fees is regulated which enables the possibility for the court to appoint an attorney to a party exempted from payment of court fees when such is necessary for protection of the rights of the party. The Law on Court Fees regulate the procedure for exemption of court fees.

5.2.3. Legal aid in juvenile justice

Presence of attorney in all cases related to juvenile justice is mandatory pursuant to the Law on Justice for Children[11] in procedure before police, social work centers, prosecution and courts. The relevant provisions are included in Articles 35, 90 and 116 from the Law.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

In North Macedonia there is no single legal aid institution, instead, depending of the type of legal aid (ex. criminal or civil) the roles of organization, provision and supervision is divided among several stakeholders.

5.3.1. Appointment, remuneration and supervision

Ministry of Justice (Министерство за правда) decides upon application for legal aid in civil and administrative issues submitted pursuant to the Law on Free Legal Aid, it appoints lawyers in individual cases, provides primary legal aid through its network of over 25 regional offices, supervises the system for free legal aid established with the Law and remunerate the providers of legal aid services for their work.

The courts (Судовите) are responsible for appointing ex-officio lawyers, reimbursement for their work as well as dismissal of the assigned counsel who has not exercised his duties in a responsible and competent manner upon request of the accused or with his or her consent. The Court informs the Bar association about the dismissal.

Bar association (Адвокатската комора) has the authority to license and disbar attorneys as well as to initiate and conduct a disciplinary procedure against attorneys for malpractice.

5.3.2. Provision of legal aid

Attorneys are responsible for providing legal aid that include representation before courts and administrative bodies on the basis of decision of the court or the Ministry of Justice.

Authorized NGOs, Legal clinics and Regional offices of the Ministry of Justice are providing primary legal aid.

5.3.3. State legal aid institution

The closest to a legal aid institution in the Republic of North Macedonia is the Ministry of Justice, more precisely, the Department for Legal Aid. This department is a sub-section of the Sector for Legal Aid and Political System and is integral part of the Ministry of Justice, without any functional independence and autonomy. Its mandate and competencies are determined directly by the Law on Free Legal Aid which creates a safety net against influences from the organs and structures above the DLA. The head of the Department for Legal Aid is appointed by the Minister of Justice. The DLA is understaffed and currently there are four employees including the head. The Department of legal aid is responsible for: management of the legal aid system, maintaining registries of legal aid providers, processing legal aid applications, supervision of legal aid providers, promotion of legal aid and coordination of the regional offices. The regional offices are not formally part of the Department but are subordinated on issues related to the legal aid. The DLA does not have formal authority to provide ADR services.

5.3.4. Delivery method

The legal aid in court and administrative procedures is provided by attorneys appointed with a decision from the court (pursuant procedural laws) or by the Ministry of Justice (pursuant the Law on Free Legal Aid). In order to be appointed, the attorneys must be enlisted in registries managed by the courts/Bar association/Ministry of Justice. The enlistment requires solely willingness to participate in the legal aid system. Specialization is only required for juvenile justice cases. Legal assistance of paralegals is not allowed. Primary legal aid may also be provided by officials from the Regional offices of the Ministry of Justice, authorized NGOs, and authorized Legal clinics. The network of over 25 regional offices of the Ministry of Justices provides to certain extent coverage to remote areas.

5.3.5. Client participation in setting priorities

The current system does not enable the client’s voice to be articulated in the governance or setting priorities though some of the concerns may be presented by the legal aid providers.

5.4. Legal aid budget

The costs incurred for legal aid services are covered by the state budget[12] though the Law on Free Legal Aid provides a possibility also by donation and other lawful incomes, however the main principle is that the State budget bears the costs for legal aid.

The State Budget, including the justice system budget as adopted by the legislator, does not include separate component concerning legal aid. The funds for legal aid are budgeted under the general budget heading[13] titled Contractual Services (425)[14]in the budgets of both, the courts and the Ministry of Justice respectively.

Chart 08. Illustrative example of location of legal aid costs in the State budget

Goods and services (42)

Contractual Services (425)

Court and Legal Services (4253)

Legal services (425310)

The determination of the legal aid budget follows the identical procedure for planning and preparing the annual state budget[15] with certain degree of autonomy for the court’s budget[16]. The courts prepare their budget projections and submit to the Judiciary Budgetary Council which prepares and submits a proposal to the Ministry of Finance. The Ministry of Justice submit their budget proposals that must be in line with its strategic documents to the Ministry of finance. The Ministry, depending on several factors, on the basis of the request prepares a draft budget and through the Government submits to the Assembly for approval. However since the legal aid budget is not a separate budget headlining there are no available information on the planning process and whether projections are made regarding this cost.

Data on the approved budget for legal aid by the by the judicial budget is not available since there are no separate heading on legal aid in the court budget. However, data on the implemented budget sub-headings and lines is available and published in the Annual reports of the Judicial Budgetary Council since 2014[17].

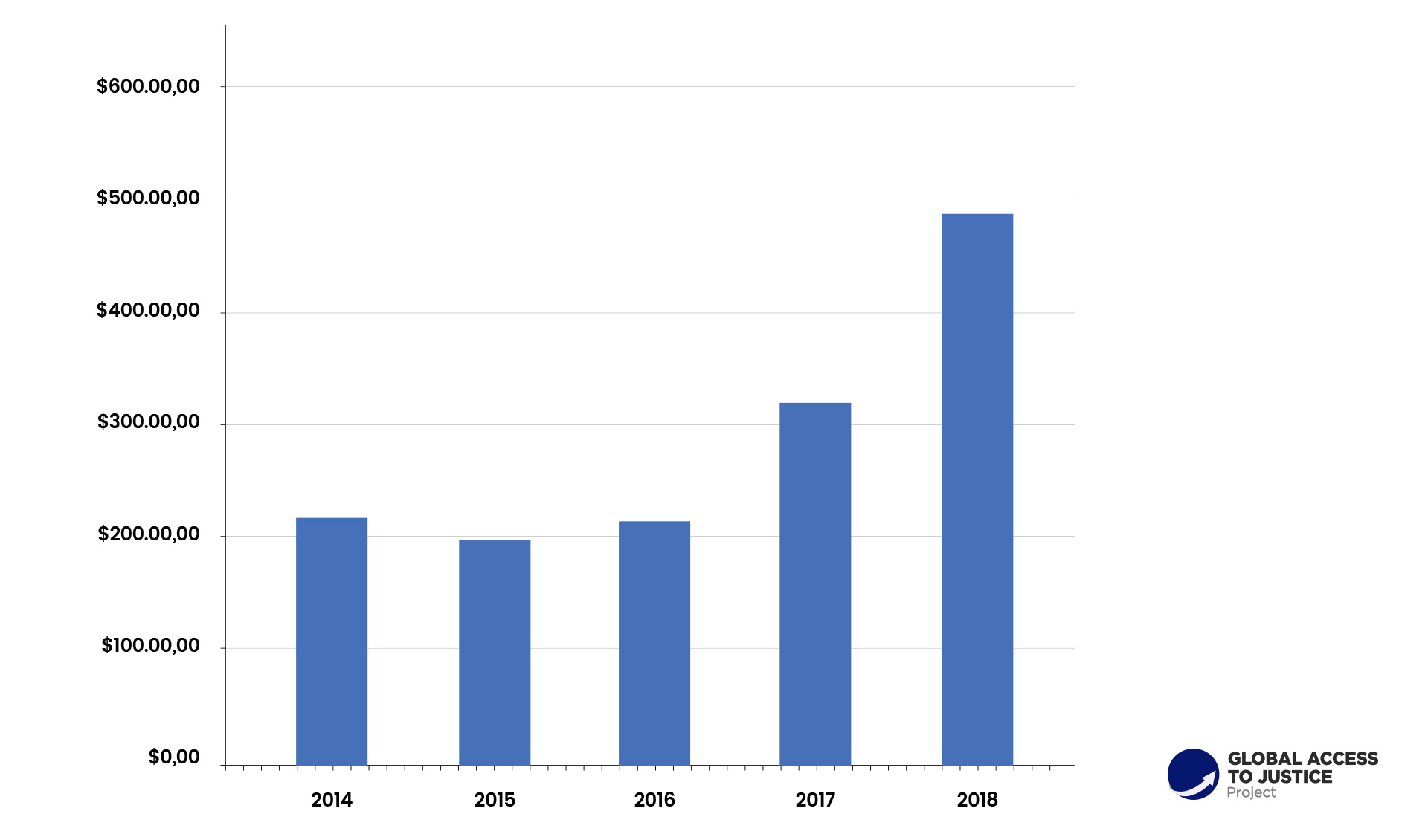

Chart 09. Annual expenditure for legal aid from the judicial budget

Chart 10. Annual expenditure for legal aid from the judicial budget in local currency and USD

Chart 10. Annual expenditure for legal aid from the judicial budget in local currency and USD

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Implemented budget for legal aid (MKD) | 11,991,000.00 | 10,927,358.00 | 12,065,296.00 | 17,856,823.00 | 27,424,413.00 |

| Implemented budget for legal aid (USD) | $216,404.98 | $197,209.13 | $217,745.82 | $322,267.15 | $494,936.17 |

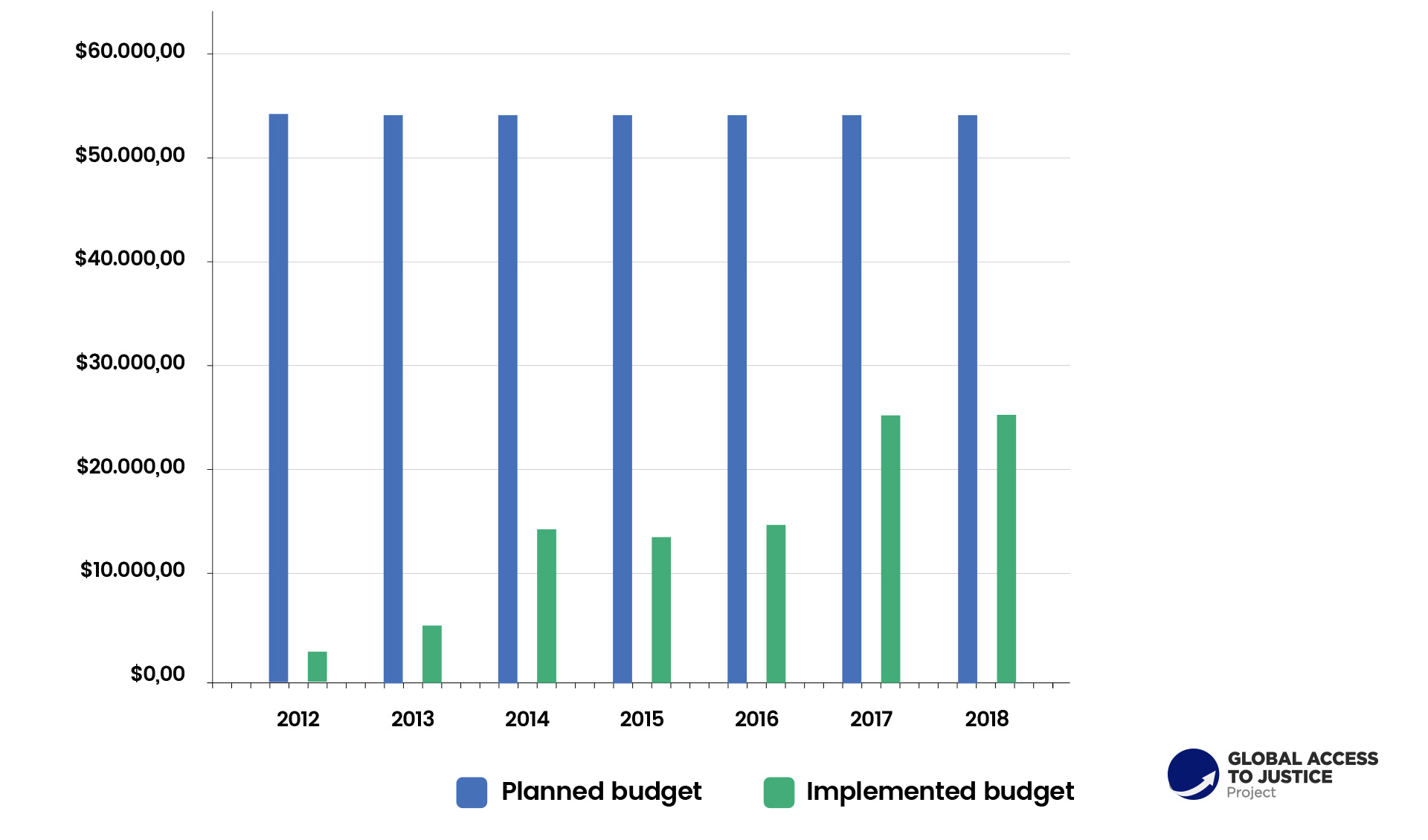

With regards to the budget for legal aid provided pursuant to the Law on Free Legal Aid and budgeted by the Ministry of Justice data is available for both, the planned and implemented funds. The data is published in the annual reports on the implementation of the law on free legal aid published by the Ministry of Justice.[18]

Chart 11. Overview on planned and implemented budget for legal aid by the Ministry of Justice

Note: The significant discrepancy by the implemented and the realized budget is due to two main reasons. The first one is the very restrictive criteria for obtaining legal aid (ex. only beneficiaries of social welfare who do not own any property) which limited the number of people obtaining this rights. The second reason is the poor promotion of the right to free legal aid. However it should be also noted that the residual of unspent fund does not accumulate in one legal aid budget, but those funds are returned after each year in the State budget.

Note: The significant discrepancy by the implemented and the realized budget is due to two main reasons. The first one is the very restrictive criteria for obtaining legal aid (ex. only beneficiaries of social welfare who do not own any property) which limited the number of people obtaining this rights. The second reason is the poor promotion of the right to free legal aid. However it should be also noted that the residual of unspent fund does not accumulate in one legal aid budget, but those funds are returned after each year in the State budget.

There is no available data broken down by a case type in the court funded legal aid. About the legal aid funded by the Ministry of Justice the data is desegregated by the type of legal aid, preliminary provided by NGOs, or representation provided by lawyers.

Chart 12. Implemented budget on legal aid by the Ministry of Justice broken down by beneficiary

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Lawyers | 28,000.00 | 212354.00 | 748,101.00 | 701,310.00 | 813,253.00 | 1,359,897.00 | 1,365,704.00 |

| NGOs | 0 | 5800 | 22,600.00 | 39,600.00 | 16,500.00 | 26,400.00 | 13,200.00 |

The legal aid service in North Macedonia has not experienced budgetary cuts for no though any initiative for its reformation toward greater outreach and coverage is blocked with the argument of insufficient funds.

5.5. Legal aid providers

5.5.1. Qualifications for legal aid providers

For the legal aid funded from judicial budget there are no specific requirements for the attorneys aside from having an active license in the Bar association and being enlisted on the list of ex-officio attorneys which does require any qualifications. However, there is one exemption to this rule. In the juvenile justice cases, where the attorney defends a minor, it must attend at least five days in year specialized training on juvenile justice.[19] This requirement is not concerning only legal aid attorneys, but also all attorneys defending juvenile defendants.

With regards to the legal aid funded by the Ministry of Justice, there are also no specific requirements for the attorneys. They only need to be enlisted in the special register for legal aid lawyers[20].

NGOs in order to be authorized[21] to provide primary legal aid must fulfill the following criteria:

- it has been registered in the Register of Associations at the Central Register of the Republic of North Macedonia for at least five (5) years prior to the application;

- it employs or has hired a graduated lawyer who has passed the bar exam;

- providing preliminary legal aid in its field is stated as a goal in the articles of the association;

- it has a liability insurance agreement for damages in providing preliminary legal aid with a policy of at least MKD 100,000;

- it has filed annual tax returns for three years prior to the registration application;

- it meets the minimum office and technical requirements that guarantee the free provision of preliminary legal aid; and

- it has completed at least three projects for providing legal aid or legal counselling.

The legal clinics needs to be an organisation unit at a faculty of law at a legally established university ranked in the top seven in the Republic of North Macedonia.[22]

5.5.2. Procedure to become a legal aid provider

Since there is no specific institution that only administers the legal aid system this question is not applicable for the national context. The staffing of the Ministry of Justice is regulated in detail with the legislation on administrative servants.[23]

5.5.3. Interest in legal aid among lawyers

There is relatively low interest among lawyers to provide legal aid within the national schemes for legal aid. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the remuneration for their fees is usually delayed. Secondly, there is inconsistent application of rules regarding the lawyer’s fees, and the payment is frequently bellow the Bar tariff. Thirdly, the process of appointment of lawyers[24], especially by the court is not transparent nor based on clear criteria (ex. random allocation, specialization or alphabetical order). There are lawyers who are enlisted, and who were never appointed, while also there are lawyers who were appointed in a disproportionate number of cases. Among the lawyers there are doubts about whether the level of actively defending the legal aid client may impact negatively on the chances to be appointed next time. All these reasons are contributing to the low interest although for some (not all) young attorneys these cases are used as an opportunity to improve their trial skills.

5.5.4. Payment of legal aid lawyers

The attorneys that provide legal aid appointed by the court are submitting report (трошковник) to the Court. The report include description of the actions taken as well as their fee calculated in accordance with the Bar tariff.[25] The Court, in the verdict or the decision that terminates the criminal procedure shall decides on the amount of the criminal procedure expenses and the person who shall be responsible to cover them.[26] With regards to the legal aid, the Court will determine the amount and will state that these costs shall be paid by the budget.

The concept for payment of the attorneys appointed by the Ministry of Justice is similar. The attorney submits a cost schedule – report to the Ministry no later than 15 days from the final decision. The attorney is compensated for provided secondary legal aid with a percentage amount of the lawyer’s reward and costs, in accordance with the Tariff for reward and compensation for lawyers’ costs of work adopted by the Bar Association.[27]

The CSO and authorized Legal clinics may receive funds for each submitted application for secondary legal aid that has been approved or through grants.

5.5.5. Level of Remuneration for legal aid work

The remuneration of the attorneys when acting as legal aid providers depends whether the legal aid is provided in criminal or civil.

In criminal procedures, at least by law, the attorneys are entitled for full remuneration for his/her services in accordance with the Bar tariff[28], without any deduction which having in mind the Tariff (as described in the Tariff) is in general an acceptable and decent compensation, comparable with the costs for fees on the regular market. Nonetheless the law states, in practice is common that the ex officio attorneys are paid bellow the Bar tariff which has its negative effects on the quality of the council.[29]

In civil procedures, the Law on Free Legal Aid from 2019 requires that the Bar association should adopt a special, discounted Bar tariff upon which the services provided by appointed attorneys will be remunerated. However, until the finalization of this report, this tariff has not yet been adopted and published. The repealed Law on Free Legal Aid from 2010[30] solution was that the attorneys shall be compensated with a 30% discounted fee from those established with the Bar tariff. The discount by law, not by a decision of the Bar association is problematic from constitutional point of view (it interferes with the autonomy of the Bar) however if applied correctly do not put the legal aid lawyers in significantly less favorable position than the other attorneys.

5.5.6. Level of independence of legal aid providers

The attorneys are legal aid providers are statutory protected from governmental interference and in general there are independent in providing legal aid and defining legal strategies. Whether the attorney in individual case will act independently or largely depend on individual competence and ability to resist pressures.

5.5.7. Special prerogatives and privileges of legal aid lawyers

The legal aid providers do not have any special privilege compared with the other attorneys.

5.6. Quality assurance

5.6.1. Responsibility for overseeing the quality of legal aid services

With regards to the legal aid provided by attorneys, there is no external institution, beside the Bar, with authority to oversee the quality of the work. Even the authority of the Bar is limited to processing complaints for malpractice. If complaint is not filed by the legal aid beneficiary, the court or the Ministry of Justice, the Bar does not perform regular or ad hoc quality check. Since the Bar is composed of attorneys, the legal aid recipients are not part of these processes.

On the other hand, primary legal aid providers, such as NGOs and Legal clinics are subject to oversight by the Ministry of Justice. The oversight is limited in determining whether the legal aid was provided in accordance with the provisions of the Law on Legal Aid.[31]

5.6.2. Monitoring quality of legal aid services

Each dissatisfied legal aid recipient may lodge a formal complaint against the attorney to the Bar association. The court and the Ministry of Justice are also obliged to notify the Bar in certain specific prescribed situations when the legal aid attorney have failed to provide diligent legal advice. Upon the receipt of the complaint, a special disciplinary prosecutor within the Bar examines the complaint and conduct a preliminary procedure which include communication with the complainer and gathering information and documentation. Within 180 days, or in exceptional circumstances additional 60 days, the disciplinary prosecutor must close the preliminary procedure and either indict the attorney or to dismiss the complaint. The disciplinary indictment is filed to the disciplinary court and served to the defendant for giving defense. The disciplinary court on public hearings examines the evidence and determining whether there was a disciplinary violation or not. If it found that such violation happened, will order certain disciplinary measure.[32]

5.6.3. Continuing education

Aside for legal aid in juvenile justice cases there is no formal requirement for continuous education.

5.6.4. Remedy for poor service

The legal aid beneficiary may request appointment of another attorney and if attorney committed disciplinary violation may lodge complaint to the Bar association.

5.7. Criminal legal aid

5.7.1. Scope of criminal legal aid

A. Legal aid during the criminal investigation phase