National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

1.1. Form of government

The Kingdom of the Netherlands consists of four parts: the Netherlands, Curaçao, Sint Maarten and Aruba (which seceded from the Netherlands Antilles in 1986). Prior to 1975, Suriname was also part of the Kingdom. In 2010 the Netherlands Antilles were dissolved and Curaçao and Sint Maarten became constituent countries within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba became direct parts of the Netherlands.[1]

The Netherlands is a constitutional monarchy. This means that the head of state is a King or Queen whose powers are laid down in the Constitution. In the Netherlands the powers of the monarch are extremely limited. Under the Constitution, the ministers, and not the monarch, are responsible for what the Government does.[2]

Dutch governments as a rule are formed by coalitions of a number of political parties owing to the electoral system of proportional representation. The government consists of ministers and state secretaries. Each ministry is headed by a government minister. There are also ‘ministers without portfolio’, who are not in charge of a ministry.

A minister may be supported by one or more state secretaries, who are entrusted with some of the minister’s tasks. The job descriptions of the state secretaries are published in the Government Gazette after their appointment and often change from government to government. If a minister is absent, a state secretary will usually stand in for them. The state secretary will, for example, attend Cabinet meetings in the minister’s place, but does not have the right to vote. A state secretary also attends Cabinet meetings if the agenda includes a topic for which he or she is responsible.

The King and the ministers together make up the Government of the Netherlands. The ministers and state secretaries are responsible for the day-to-day business of government. On 26 October 2017 the third government led by Mark Rutte took office.

1.2. Demographics, ethnic groups, languages and religion

The Netherlands has more than 17 million (17.181.084 on January 1st of 2019) registered inhabitants.[3] About 76% of them were born in the Netherlands and 24% were born elsewhere. The largest groups of migrants were born in Germany (2%), Indonesia (2%), Morocco (2%), Turkey (2%), and Suriname (2%).

The official language of the Netherlands is Dutch, spoken by almost all (native) people in the Netherlands. There are also some recognized provincial languages and regional dialects.[4]

- Frisian is a co-official language in the province of Friesland. Frisian is spoken by 453,000 speakers.

- English is an official language in the special municipalities of Saba and Sint Eustatius (BES Islands), as well as the autonomous states of Curaçao and Sint Maarten. It is widely spoken on Saba and Sint Eustatius

- Papiamento is an official language in the special municipality of Bonaire. It is also the native language in the autonomous states of Curaçao and Aruba.

- Several dialects of Dutch Low Saxon (Nederlands Nedersaksisch in Dutch) are spoken in much of the north-east of the country and are recognised as regional languages according to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Low Saxon is spoken by 1,798,000 speakers. Another Low Franconian dialect is Limburgish, which is spoken in the south-eastern province of Limburg. Limburgish is spoken by 825,000 speakers. Though there are movements to have Limburgish recognised as an official language (meeting with varying amounts of success) it is important to note that Limburgish in fact consists of many differing dialects that share some common aspects, but are quite different. However, both Low Saxon and Limburgish spread across the Dutch-German border and belong to a common Dutch-German dialect continuum.

In 2015, Statistics Netherlands, the Dutch government institute that gathers statistical information about the Netherlands, found that 50.1% of the adult population declared to be not religious. Christians comprised 43.8% of the total population and were divided between Catholics with 23.7% and the members of the Protestant Church of the Netherlands with 15.5%, members of other Christian denominations were the 4.6%. Islam comprised 4.9% of the total population, Hinduism 0.6%, Buddhism 0.4% and Judaism 0.1%. A large majority of the Dutch population believes that religion should not have a determining role to play in politics and education. Religion is also decreasingly seen as a social binder, and is generally considered a personal matter which should not be propagated in public.[5]

1.3. Gross domestic product (GDP) and gross national income (GNI)

| Year | GDP

in (million) Euro[6] |

GNI (PPP), Atlas method

in (million) US$[7] |

| 2009 | 655,958 | 53,670 |

| 2010 | 664,765 | 53,900 |

| 2011 | 675,077 | 54,480 |

| 2012 | 668,121 | 52,930 |

| 2013 | 667,252 | 52,950 |

| 2014 | 676,749 | 51,980 |

| 2015 | 690,008 | 49,810 |

| 2016 | 705,131 | 46,900 |

| 2017 | 725,657 | 46,870 |

| 2018 | 744,505 | 51,260 |

1.4. Human development indicators

The inequality index in the Netherlands is 0.28.[8]

In 2017 the poverty figure was just under 939,000. That is 5.7% of the Dutch population.[9] People on welfare, non-Western immigrants, and single mothers with underage children run the greatest risk of poverty, according to the SCP. In 2016 a total of 280 thousand children lived in poor homes, almost 9 percent of all Dutch kids.[10]

Life expectancy at birth is 81.78 years (in 2018). For women the life expectancy is somewhat higher (83.33 years) than for men (80.16 years).

On average 1.59 children are born per woman (2018).[11]

The expected years of schooling are 18 years, somewhat higher for women (18.3 years) than for men (17.8 years). People in the Netherlands on average receive 12.2 years of schooling (women 11.9, men 12.5 years).[12]

Netherlands’ HDI value for 2017 is 0.931— which puts the country in the very high human development category—positioning it at 10 out of 189 countries and territories. Between 1990 and 2017, Netherlands’ HDI value increased from 0.829 to 0.931, an increase of 12.3 percent. Netherlands’ 2017 HDI of 0.931 is above the average of 0.894 for countries in the very high human development group and above the average of 0.895 for countries in OECD. From OECD, countries which are close to the Netherlands in 2017 HDI rank and to some extent in population size are Belgium and Sweden, which have HDIs ranked 17 and 7 respectively.[13]

Between 1990 and 2017, Netherlands’ life expectancy at birth increased by 5.0 years, mean years of schooling increased by 2.0 years and expected years of schooling increased by 3.3 years. Netherlands’ GNI per capita increased by about 49.8 percent between 1990 and 2017.

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Court system

The Netherlands has an inquisitorial system. It has a civil law legal system incorporating French penal theory. Independence from Spain and the Holy Roman Empire in 1648 left a Roman law tradition, which continued to be developed into a discrete system of Roman Dutch law. French capture of the Netherlands in 1795 gave rise to the abolition of Roman Dutch law in 1809 and the introduction of the French civil code in 1811. The French legal system remained even after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. After Belgium has seceded, a new Civil Code was introduced in 1838, with other codes following. A major revision of the Civil Code led to a ‘new’ Civil Code which came into force between 1970 and 1992. The Constitution was established in 1814 but has been revised repeatedly. The most recent full revision was in 1983.[1]

The court system in the Netherlands comprises different areas of law and a variety of bodies. Judges are independent and cannot be dismissed by the Minister of Justice and Security.[2]

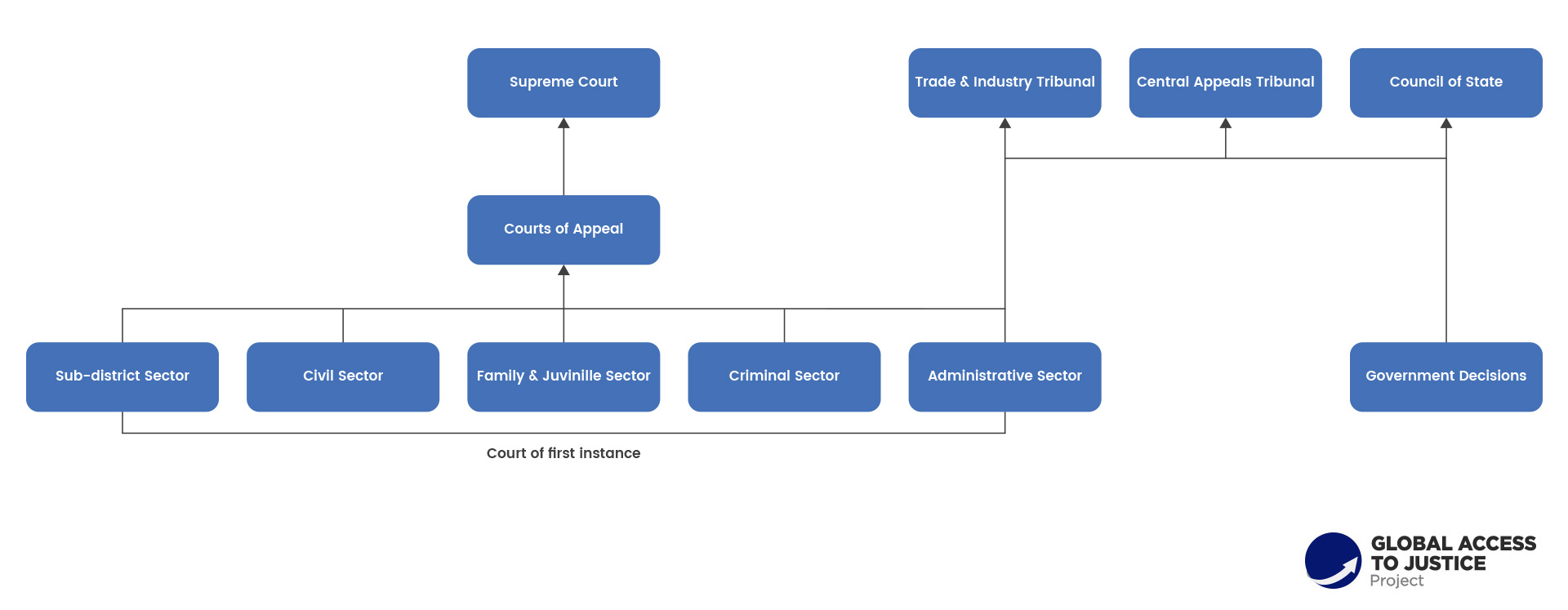

Below you can find an schematic overview of the Judiciary System in the Netherlands.

Chart 1. The Judiciary System in the Netherlands.

The Netherlands is divided into 11 district courts, 4 courts of appeal and 1 Supreme Court. Most cases start at a district court. Every district court has a limited jurisdiction sector (the cantonal court), which hears cases such as employment or rent disputes, and civil cases involving claims of up to €25,000. This sector also hears cases involving minor criminal offences (misdemeanours).[3]

The Netherlands is divided into 11 district courts, 4 courts of appeal and 1 Supreme Court. Most cases start at a district court. Every district court has a limited jurisdiction sector (the cantonal court), which hears cases such as employment or rent disputes, and civil cases involving claims of up to €25,000. This sector also hears cases involving minor criminal offences (misdemeanours).[3]

To safeguard the quality of the justice system and to make the courts accessible to everyone, the Netherlands is divided into jurisdictions. This division determines, among other things, which district court will hear a given case.

2.1.1. District courts

The Netherlands is divided into 11 districts, each with its own court. Each district court has a number of sub-district venues. The district court is made up of a maximum of five sectors. These always include the administrative sector, civil sector, criminal sector and sub-district sector. Family and juvenile cases are often put into a separate sector, as is sometimes the case with the administration of the law concerning aliens. The court board is free to determine such matters.[4]

2.1.2. Sub-district sector

It is relatively simple for ordinary citizens to have their case heard in the sub-district sector. They have the right to argue their own case and do not need a lawyer to represent them in court. Cases are handled by a single judge.

In terms of civil law, the sub-district judge deals with all cases involving rents, hire purchase and employment.

In criminal law, the sub-district judge only deals with minor offences, not serious offences. Often these are cases in which the police or the public prosecutor has proposed a settlement. If the accused refuses to accept such a proposal, then the case comes before the sub-district judge. The sub-district judge usually delivers an oral judgment immediately after the hearing.

2.1.3. Criminal law

The judges of the criminal law sector deal with all criminal cases which do not come before the sub-district judge. These cases can be heard by a single judge or in full-bench panels with three judges. The full-bench panel deals with more complex cases and all cases in which the prosecution demands a sentence of more than one year’s imprisonment.

2.1.4. Civil law/family law

The civil sector handles cases not specifically allocated to the sub-district judge. Most of these cases are decided by a single judge, but here too there are full-bench panels with three judges to deal with more complex cases. A number of district courts have a separate sector for family and juvenile cases, when the number of such cases is considerable.

2.1.5. Administrative law

With only a handful of exceptions, administrative disputes are heard by the district court; in many cases the hearing by the administrative law sector is preceded by an objection procedure under the auspices of the administrative authorities. It is usual for these cases to be heard by a single judge, but here too the district court can decide to appoint three judges to a case which is complex or which involves fundamental issues.

Tax cases also fall under the administrative law sector.

If the district court in question has no separate sector to handle cases governed by the law concerning aliens, such cases are dealt with by the administrative law sector or a division thereof.

In cases involving civil servants and social security issues, appeal is a matter for a special appeals tribunal, the Central Appeals Tribunal, and in most other cases for the Administrative Jurisdiction Division of the Council of State.

2.1.6. Appeal

The eleven districts are divided into four areas of Court of Appeal jurisdiction: The Hague and Amsterdam in the west, Arnhem-Leeuwarden in the east and in the north and ‘s-Hertogenbosch in the south.

With regard to criminal and civil law, the justices of the Court of Appeal deal with cases where an appeal has been lodged against the judgment passed by the district court. The Court of Appeal re-examines the facts of the case and reaches its own conclusions. In most cases it is possible to contest the Court of Appeal’s decision by appealing in cassation to the Supreme Court of the Netherlands.

In addition to criminal and civil cases, the Court of Appeal also deals with all appeals against tax assessments, in its capacity as administrative court.

2.1.7. Special tribunals

There are three special tribunals in the Netherlands that are competent in specific areas of administrative law.

(i) The Central Appeals Tribunal is a court of appeal which is mainly active in legal areas pertaining to social security and the civil service. In these areas it is the highest judicial authority. The Tribunal is based in Utrecht.

(ii) The Trade and Industry Appeals Tribunal, also known as Administrative High Court for Trade and Industry, is a specialized administrative court which rules on disputes in the area of social-economic administrative law. In addition, this appeals tribunal also rules on appeals for specific laws, such as the Competition Act and the Telecommunications Act. The Tribunal is based in The Hague.

(iii) The Administrative Jurisdiction Division of the Council of State in The Hague is the highest administrative court with general jurisdiction in the Netherlands. It hears appeals lodged by members of the public, associations or commercial companies against decisions by municipal, provincial or central governmental bodies. Disputes may also arise between two public authorities. The decisions on which the Division gives judgment include decisions in individual cases (e.g. refusal to grant a building permission) as well as decisions of a general nature (e.g. an urban zoning plan).[5]

2.1.8. Supreme court

As the highest court in the fields of civil, criminal and tax law in the Netherlands, the Supreme Court is responsible for hearing appeals in cassation and for a number of specific tasks with which it is charged by law. The aim of cassation is to promote legal uniformity and the development of law. The court examines whether a lower court observed proper application of the law in reaching its decision. At this stage, the facts of the case as established by the lower court are no longer subject to discussion.

An Attorney General’s office is attached to the Supreme Court. Its members main task is to provide the Supreme Court with independent advice, known as an advisory opinion, on how to rule in a case.

Not only judgments of courts of appeal can be appealed in cassation, also judgments of the Joint Court of Justice of the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba can be appealed in cassation to the Supreme Court.[6]

2.1.9. Facts and figures

| Number of Dutch court cases – 2018 (x 1,000) | ||||

| Civil | Criminal | Administrative | Total | |

| First instance | 1.113 | 269 | 93 | 1.475 |

| Appeal | 13 | 32 | 13 | 58 |

| Total | 1126 | 301 | 106 | 1.533 |

Source: Raad voor de Rechtspraak/ Council for the Judiciary

2.2. Legal profession

The Netherlands Bar Association (the NOvA) is the public law professional body for all advocates in the Netherlands. The statutorily-regulated core activity of the Bar is to oversee the quality of services by advocates. This quality is ensured by, among other things: a comprehensive education programme for the legal profession, drawing up by-laws and other binding rules for advocates, disciplinary proceedings, information and services to the members, and advice to the Dutch government about policy plans and enactments. By law, an advocate must become a member of the Bar. In 2018, there were 17 784 advocates registered.[7]

2.2.1. The Netherlands Bar Association (the NOvA)

The NOvA was established by the Act on Advocates (Advocatenwet) with effect from 1 October 1952. All lawyers in the Netherlands jointly form the NOvA. The NOvA is established by law, but does not receive any government funding. All costs incurred by the NOvA are being paid for by the lawyers through an annual financial contribution to the Netherlands Bar. As a result, the NOVA is completely independent of the government.[8]

The Netherlands is judicially divided into eleven judicial districts (regions), the jurisdictions of the courts. The lawyers in a judicial district form the (local) bar within the judicial district where the lawyer holds office. Each local bar is chaired by a council of the local bar (raad van de orde) and a local bar president. A local bar president is chosen by the lawyers in the judicial district. The local bar president is responsible for the supervision of all lawyers in the judicial district.

The general management is a task of the general council (algemene raad, AR). The NOvA is headed by a secretary general. The secretary general is in charge of the daily management.

The general council is supported by the office of the NOvA. The office carries out policies and prepares proposals which are of importance to the legal profession. The office consists of four departments: Communications, Finance and Organization, Policy and Regulations and Supervision. The office employs approximately 60 employees.

The NOvA draws up regulations and rules (for example the Code of conduct) for the legal profession: the Legal Profession By-law and the Legal Profession Regulations. The adoption thereof is done by the board of representatives (college van afgevaardigden). The 54 deputies of the board are all chosen by lawyers in their own judicial district/region.

The NOvA is a member of the International Bar Association (IBA) and the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE).

The Act on Advocates governs the profession of lawyers. Under this law, the lawyer is compulsory part of the NOvA. On the basis of this Act, the NOvA may lay down rules for the professional practice, such as the financial administration and compulsory professional insurance. The lawyer is required to undergo continuous training on a yearly basis and is monitored thereon by the central monitoring of the regulations for continuous training.

The bar registration (tableau) contains all lawyers who may exercise their profession within the eleven judicial districts (regions) in the Netherlands. This national list is being maintained by the bar registration. The list includes the office name, business address, phone numbers, data of the lawyer such as name, date of birth and e-mail address, and other practical information. Lawyers are registered after having been sworn in or after admission if they meet all requirements. Disbarment can take place at own request, by a decision of the disciplinary board or after the expiration of a conditional registration.

In principle it is not permitted that non-lawyers are owning and managing a law office. The system of practice of a lawyer in service is a closed system. Exercising the practice in the service of another person is not permitted, except for the enumeration in the Legal Profession By-Law. The enumeration is for example made for an insurer who only practises legal expenses insurance. With this closed system the independence of the lawyer must be guaranteed. Legal independence in the sense of discretion and uncompromising service to the client’s interest, means that the lawyer can decide for himself how he will handle the case.

2.2.2. Legal representation by a lawyer

Whether one should engage a lawyer depends on the situation. This differs per type of court case and per court handling the case. According to the law, a lawyer is required in certain legal proceedings. This concerns all civil proceedings (with the exception of cases before the sub-district court) and all family law proceedings. In addition, a lawyer is required in some more specific cases, for example when you want to apply for your bankruptcy or moratorium.

In some cases, a lawyer is not mandatory. This applies to cases before the sub-district court, to cases before the criminal court and to cases before the administrative court. For example, for disputes within labor law, prosecution within criminal law (also on appeal), tenancy law and administrative law in general, and for monetary claims up to 25,000 euros.[9]

There is some discussion in society and parliament about the affordability of lawyers fee. In particular, middle-income citizens who do not have access to the legal aid system complain about access to a lawyer. Those seeking justice who fall just outside the system of legal aid experience great inequality with those seeking justice who do qualify for legal aid, although there are many opportunities for private legal aid assurance in the market.

The proposed revision[10] of the system of legal aid also includes measures that may have a positive impact on access to justice for those middle incomes. For frequently occurring legal problems, the Minister of Legal Protection wants to start working with ‘legal aid packages’. The starting point here is that a legal aid package provides for the treatment of a problem for an integral price. People with legal problems who are entitled to legal aid can receive a legal aid package. These legal aid packages will not only become available for litigants within the legal aid system, but possibly also (on the commercial market) for those who are not entitled to legal aid. They must bear the costs of this themselves, but the new system does have the advantage that it is clear in advance which form of assistance is offered, at what quality and at what costs.

2.2.3. Paralegals (2i)

First line legal aid is provided by paralegals with an academic degree or higher vocational education in charge of the Legal Services Counters and by volunteers that work in law shops. Also social counselors play a role.

Second line legal aid is mainly provided by lawyers/members of the Netherlands Bar Association and by mediators/members of The Dutch Mediation Institute (NMI, see below). A smaller amount of cases is handled by paralegals with an academic degree or higher vocational education who work for consumer organizations, insurance companies and other providers in charge of unions.

The Dutch Mediation Institute (NMI) is an independent institute which aims to raise awareness of mediation in the Netherlands and improve the standard of the services available. The NMI has developed various models and rules for this purpose.[11]

The NMI also manages a national register of mediators which includes only qualified mediators. These mediators will have completed a basic mediation training recognised by the NMI and then passed a theory exam and an assessment. NMI registered mediators are required to keep their knowledge and skills up to date, and this will be verified by the NMI. The register can be consulted at: NMI Register of Mediators.

The site also contains independent information about mediation and mediators in the Netherlands. You can search for information on the site according to your own interests and preferences, using criteria tailored to your needs. For example, you can look for a mediator with specific expertise in a particular area.

Mediators can register at the NMI, and must then adhere to the code of conduct for mediators. Registration is voluntary (as is adherence to the code of conduct), but mediators wishing to work within the Dutch system of legal aid or referral by the courts must register with the NMI and also obtain accreditation and undergo an assessment.

The Netherlands has also introduced an initiative on court-connected mediation, called ‘Mediation naast rechtspraak’. This means that the district court or court of appeal hearing your case will alert you to the possibility of opting for mediation. It may do this in writing, in which case both parties will receive a letter with an information leaflet, the mediation self-assessment and a reply form. Alternatively, the judge may indicate at the hearing that your case is suitable for mediation and propose this option to you and the other party.

You can also approach the mediation officer yourself. Each district court and appeal court will have such an officer who can answer your questions, put your proposal for mediation to the other party, help the parties to find the right mediator and arrange the first meeting.

Mediation is always allowed and is most frequently used in civil law and public law.

2.2.4. Judges and their careers

Judges are independent and no Minister has authority over them, with the exception

that the budget for the running of the courts is a part of the wider budget of the Ministry of Justice. The budget is allotted to the courts by the Council for the Judiciary (Raad voor de Rechtspraak) and the courts are accountable to the Council for the Judiciary with regard to how they utilize their resources. The Minister thus is only responsible for the functioning of the judiciary as a whole.[12]

This Council is the board for 11 courts, 4 courts of appeal, the Central Board of Appeal (Centrale Raad van Beroep), and the Central Board of Appeal for trade and industry (College van Beroep voor het bedrijfsleven). The Supreme Court (Hoge Raad) and the Administrative Law Division of the Council of State (Afdeling Bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State) do not fall under the Council for the Judiciary.

The main prerequisite to being eligible for training to become a judge is an excellent law degree. Candidates must also pass a psychological examination, as well as interviews with the National Selection Committee for the Judiciary, which consists of legal and non-legal professionals. The psychological test is an analytical/cognitive one, testing individual intelligence; whereas the interviews with members of the selection committee test communicative skills, the ability to make and motivate sound decisions. This procedure takes eight weeks. Candidates who are selected are appointed by the Justice Minister as trainee with one of the nineteen courts.

Trainees are required to undergo six years of training. The training is a mix of theory and practice. The theory consists of courses provided by the magistrate’s academy, the so-called study center for the administration of justice in Utrecht (Stichting Studiecentrum Rechtspleging). During the six years training period, the trainee is required to undergo four years in service training (both within the court administration and within the prosecution service) and two years external training in a law office or a company or at a police office. The main aim of the external training is to provide the trainee with work experience in a different area of the legal profession. After four years in service training the trainee chooses either for a post within the judiciary or within the prosecution service. At the end of the trainee period, the candidate is appointed as deputy prosecutor or deputy judge. After a year, they are appointed as prosecutor or judge.

There is a second route to becoming a judge or public prosecutor; so-called ‘outsiders’ are also recruited by the service. Outsiders are legal professionals (lawyers, academics, civil service officers) over the age of thirty with professional work experience of more than six years with an interest in becoming a judge or public prosecutor. They can apply for a position within the judiciary or prosecution service and are invited for interviews with the members of the National Selection Committee for the Judiciary. In the majority of cases, those candidates that pass selection by the Selection Committee serve for approximately a year as a deputy judge or deputy prosecutor in order to allow their competences and abilities to be assessed. After that year, the collegial council of the court or the Chief Public Prosecutor may recommend to the Government the candidate’s full appointment.

When they succeed in their education, they will start to work as a judge. They are appointed to office for life. In the Netherlands there are 2.489 judges (December 2018).[13] From all the judges 60% is female and 40% male.[14] Judges may work untill they are 70 years old (Art. 117 Constitution juncto art. 46 h Law for the legal status judicial officials). The age of 70 is a compulsory retirement age. They can also be laid off earlier at their own request. Judges can be transferred to another court without his/her consent for organizational reasons. Most courts work in different places, so all the places have to be staffed.

2.2.5. Public prosecutors and their careers

The prosecution service is a nation-wide organization of prosecutors.[15] It is organized hierarchically. At the top is the Board of Prosecutors General. The service functions under the responsibility of the Minister of Justice and Safety, but is not an agency of the Ministry. The prosecution service functions independently from the Minister, who can’t give orders of Justice. The service is part of the judiciary, but its position differs from that of the other part of the judiciary, that is, the judges. The judges are independent, have life tenure, and are separate from the Ministry of Justice. Public prosecutors are civil servants, may be fired and fall under the political responsibility of the Ministry of Justice.

The main task of the prosecution service is to administer, by means of criminal law, the legal order. The prosecution service plays a pivotal role in the administration of criminal justice. The decisions made by the public prosecutor involve profound consequences for the offender, and repeated refusals to prosecute certain crimes may also lead to a decline in the detection and investigation of offences by the police. In turn, the charges laid against the accused largely delineate the adjudicatory functions of the courts.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Dutch prosecution service has enormous powers, at least in dealing with criminal cases. It has a monopoly over prosecutions, and employs the expediency principle in this connection. Furthermore, it makes use of its hierarchical structure to pursue a coordinated policy. In this way, the prosecution service is able to determine systematically what cases should be brought to trial, and what sentences the courts should be asked to impose.

If the public prosecutor decides to prosecute, (i.e. if a notification of further prosecution or a summons is issued), the accused can lodge a written notice of objection with the district court. The objection procedure enables the suspect to challenge in a nonpublic setting (i.e. in chambers) what may be a rash or unjust prosecution, and thereby avoid the exposure of a public trial.

This judicial review of the decision to prosecute is fairly limited. In the great majority of cases, the notice of objection procedure results, after a brief investigation, in a decision by the judge in chambers that the case should go to trial after all. Should the court find that a prosecution is unjustified, the case will be dismissed. Otherwise, the case is prepared for trial. The grounds on which the prosecution may be dismissed are limited to four:

- where the case is to be dismissed because the prosecutor no longer has the right to prosecute, e.g. due to the statute of limitations;

- where the evidence against the accused is manifestly insufficient;

- where the act does not constitute a criminal offence; and

- where the accused is not liable, e.g. due to self-defense.

The statutory requirements for becoming a public prosecutor are possession of Dutch nationality and a university law degree (sects 1c and 1d Legal Position of Judicial Civil Servants Act). Supplementary professional requirements are laid down in the Royal Decree concerning the Education of Judicial Civil Servants. Every judicial civil servant has to follow a training program of six years. This program comprises an internship at a district court and a district prosecution office, an external internship and further theoretical education to improve professional skills, abilities and knowledge. The training program is the same for all judicial civil servants independent of their intention to become a public prosecutor or a judge. Annually, the judicial civil servant in training will be assessed during the training program. Before an applicant will be selected to follow the internship program the National Selection Committee for the Judiciary will ask for written information about the applicant from referents, will interview the applicant and will take note of the results of a psychological test of the applicant.

There is a second route to becoming a judge or public prosecutor; so-called ‘outsiders’ (see above).

Public prosecutors can be laid off at their own request. They can be dismissed when there is an investigation they committed crime themselves. Approximately 950 public prosecutors are employed in the Netherlands.[16]

2.2.6. Shortage of legal services

There is a broad variety of legal aid services. Research shows that there seems to be no shortage of legal services in the Netherlands.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

If the police takes someone into custody, the Legal Aid Board (Raad voor Rechtsbijstand) will take care of immediate legal representation to provide legal assistance free of charge. Within 2 hours a ‘piket’ (‘assigned’) solicitor will visit the suspect and help him answer the judicial questions asked by the police. The suspect can also ask for his own lawyer.[1]

When someone commits a crime, the public prosecutor together with the police will start an investigation. The prosecution will take place in de court of the district where the crime has been committed. Depending on de kind of crime, the suspected offender will be prosecuted by one judge (offense, simple cases) or three judges (a full-bench panel in difficult cases like murder, rape, drug trafficking etc.).

When someone is caught red-handed the suspect can be hold into custody for a period of 6 hours when he is suspected of a minor offence. When it concerns a major offence the suspect can be hold into custody for a period of 9 hours. The time between midnight and 09.00 a.m. will not be taken into account for these terms. After this period the suspect will either be released or insured.

When the suspect is still in custody, the public prosecutor can extend the period for 3 days. These 3 days can be extended with another 3 days. When the investigation is not yet ready, the public prosecutor can ask the examining magistrate for another period of 14 days. When the examining magistrate finds it necessary that the suspect stays inside, he will extend the custody for 14 days. The suspect will at least see the examining magistrate after 3 days and 18 hours after his arrest.

The court, consisting of 3 judges, will decide over the extension of the detention for a period of 30 to 90 days. The court will check:

- Crimes punishable by more than 4 years;

- If the suspect has a permanent residence;

- If there are serious objections against the suspect;

- If there is a hazard of flight;

- If there is a shocked legal order;

- Whether the police needs more time to investigate.

The public prosecutor can dispose of minor criminal cases, such as criminal damage, vandalism, shoplifting and traffic violations, by imposing a sanction (strafbeschikking).[2] In this situation the case is not brought before the court. The Public Prosecution Service itself decides on the sanction imposed once it has been established that the suspect is guilty of the offence in question. The sanction could be a fine, a driving ban (for up to six months), an alternative sanction (e.g. up to 180 hours’ community service) or a compensation order. The Public Prosecution Service may not impose a prison sentence; only a court may do that. Suspects who accept the sanction thereby admit their guilt. And if they decide to reject the sanction, they can have their case brought before the court.

One magistrate can impose no more than 1 year imprisonment. When there are 3 magistrates, they can impose life imprisonment. In the Netherlands life imprisonment means that the sentenced will stay in prison his whole life. After 25 years the sentenced can ask the court if they find it necessary to lock him away for his whole life. He can also place a gratitude request (ex. art. 558 Code of Criminal Procedure of the Netherlands). Life imprisonment is only imposed in a few cases per year.

When a convicted person does not agree with his sentence he can appeal within 14 days. In the Netherlands there are 4 courts of appeal. The case will be completely revisited. The last step is to go to the Supreme Court, also within 14 days. The Supreme Court will only look of the law was respected and to take care of the legalization and the unity of the law in our country.

In the Netherlands when a crime is committed, the police starts an investigation. A victim of a crime can place a declaration about the personal consequences of the crime (f.e. damages) of the crime which was committed against him and can give an opinion on the sentence. When a criminal offense is not prosecuted, the victim can lodge a complaint in writing by the court of appeal (ex. art. 12 Code of Criminal Procedure of the Netherlands). The court of appeal can order the prosecution of the offender.

The offender will be summoned for the trial. The offender will be obliged to be in trial. Sometimes it is possible to have a trial in absentia of the offender (see art. 279-280 Code of Criminal Procedure of the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands the courts, the courts of appeal and the Supreme Court can ask questions to the European Court of Human Rights and all the judges will take the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights into their considerations in the cases they will have to decide.

3.2. Civil Procedure

In the Netherlands we have different procedures which will fall under the terminology Civil Procedure:

1. Civil procedure: This area contains cases between citizens or corporations;

2. Administrative procedure: Cases between citizens and the government (like social welfare, immigration, spatial planning, permits, taxes);

3. Family procedure: Cases like adoption, divorces, division of property.

3.2.1. Civil Procedure

In Civil Procedure the subdistrict court judge deals with rental cases, labour matters and cases under the € 25.000,00. Beside the subdistrict court judge the civil judge can be found in cases between citizens. When a citizen has a conflict with another citizen he can subpoena the other citizen and they will meet in court. The court is the same as in penal procedures, only another chamber. You will start in court, after that you can go to the court of appeal and finally to the Supreme Court.

3.2.2. Administrative procedure

In administrative procedure a litigant can go to the court (another chamber, the administrative chamber) when he has a conflict with the government. When a citizen disagrees with authorities, he has to complain first at the authorities. The authorities have an independent objection committee that speaks with the citizen and a representative of the administrative body and advises the government on the decision that has to be taken. When this complaint-proceeding doesn’t solve the problem, the citizen can go to court. When the citizen or the authorities object to the judgment of the court, they can appeal to:

· Central Board of Appeal (Centrale Raad van Beroep, social welfare, official – ambtenarenrecht)

· Central Board of Appeal for trade and industry (College van Beroep voor het bedrijfsleven, economic administrative law, agricultural subsidies, healthcare rates, telecomrates, Fertilizers Act, Forestry Act, disciplinary judge for chartered accountants)

· Administrative Law Division of the Council of State (Afdeling bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State, Environment, spatial planning, environmental permits, grants (subsidies), educational decisions, asylum and residence permits)

· The Supreme Court (Hoge Raad, penal, civil, taxes)

3.2.3. Family procedure

In family procedures the court can decide that children should need supervision (ondertoezichtstelling) or out-of-home placement (uithuisplaatsing). The judge is advised by the child protection board (Raad voor de Kinderbescherming). The court will also decide in cases of problematic divorces.3.2.4. Summary procedure / Preliminary injunctionWhen a citizen or an authority thinks his case is an urgent matter, he can ask for a summary procedure (kort geding) in civil and family cases. In administrative cases he can ask for a preliminary injunction. These procedures go faster.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

Alternative dispute resolution, for example in the form of mediation, is on the increase in the Netherlands, however it is still rare in construction-related disputes. Apart from mediation, disputes can also be resolved on the basis of binding advice, in which case the litigants jointly appoint an expert who will deliver a (binding) judgment on the issue at hand. In short, alternative dispute resolution is possible in the Netherlands, albeit that parties do not often avail themselves of this possibility.

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

Online self-help, information and support is offered on the Rechtwijzer website (Roadmap to Justice)[3]. Rechtwijzer is a preliminary provision and offers interactive ‘decision trees’ helping people to assess their situation. In addition, Rechtwijzer provides easy-to-understand information and guidance on possible solutions for the most common legal problems. Rechtwijzer combines publicly run guided pathways for common legal problems with online products and services from private service providers.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

Under the European Convention on Human Rights and the Constitution of the Netherlands, each citizen of the Netherlands has the right to access courts, apply for legal advice and representation and, if means do not suffice, receive state-financed legal aid.[1] The Dutch Legal Aid system provides legal aid to people of limited means. Anyone in need of professional legal aid but unable to (fully) bear the costs, is entitled to call upon the provisions as set down in the Legal Aid Act (in force since 1994; the last amendment in the regulations took effect on February 1st, 2015). The Legal Aid Act of 1994 replaced the prior statutory system that dealt with the supply of legal aid and dates back as far as 1957.

Residing under the competence of the Ministry of Justice & Security (J&S), an independent governing body called the Legal Aid Board (‘Raad voor Rechtsbijstand’, LAB) is entrusted with all matters concerning administration, availability, organization, supervision and expenditure as well as with the actual implementation of the Legal Aid System.

There is consensus in the Netherlands that access to justice must be guaranteed. However, there are differences of opinion about how far this access should go, how self-reliant people should be expected and to what extent the needs of people are met. The group that suffers the most in this respect is perhaps the group of people who fall just outside the system in terms of income. They earn too much to be able to use legal aid, but too little to be able to pay a regular rate for lawyers although there are many opportunities for legal aid assurance in the market.

It is generally thought that people in the Netherlands have sufficient opportunities to come into contact with first-line or second-line legal aid providers. There is no indication that people cannot find suitable help. There is, however, an ongoing discussion about the reimbursement of legal aid providers. The legal profession and the Minister have different ideas about this.

In November 2015 the Wolfsen Committee submitted a report to the Dutch Minister of Security and Justice entitled ‘Reassessing Legal Aid Towards a Durable System for Legal Aid’. The Wolfsen Committee suggested to organise the system in another way. These proposals focused on strengthening the first-line legal aid, increasing the quality of legal aid, a more bundled and multidisciplinary approach to legal problems, and investigating a possible increase in lawyers’ fees.

In October 2017, the Committee Van der Meer investigated the adequacy of the regulation on lawyers’ fees within the legal aid system. They announced its findings on the basis of a detailed time registration study and came to the conclusion that there is serious backlog in the system, as lawyers in almost all areas of justice and types of cases spend on average much more time than they are reimbursed. In order to be able to bring up to date the current fixed fees, which are based on an approximately twenty-year-old time registration study by the committee Maan, the annual budget for the legal aid system should be increased by approximately € 125 million. However, that outcome did not fall within the precondition of budget neutrality that the Committee had been given. Since then, much has been said about the remuniration of the legal profession within the system. The legal profession is of the opinion that there must first be an increase in the rates before changes are made to the system, while the Minister first wants to implement changes to the system and only wants to increase the rates in the long term if the number of cases decreases after the changes. By way of temporally measurement the hourly rates were raised with 10 % on January the first 2020.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

Below you can find the milestones of the legal aid system in the Netherlands:

1956: First Legal Aid Act. It guaranteed legal title to legal aid, especially for support by a lawyer in court.

1969: Opening of first Law Shop in Tilburg by law students. From that moment on in almost every big city. Focus on poor people and social rights (labour, social benefits, housing).

1975: First Legal Aid and Advice Centre (LAAC). Network all over the country and subsidised by Ministry of Justice. First line service and assessment of applications.

1978: Legal Aid in the constitution. Strong grow of. Reasons for problems (unfair competition with the BAR, focus more on proceedings).

1994: The new Legal Aid Act. Introduction of 5 legal Aid Boards. Clear separation between organising and supervision on one side and providing legal aid on the other side.

1998: Positive evaluation by Minister and adopted and supported in.

2000: Committee Maan. New fixed fee system.

2001: Looking into the future. In 2000 a research report came out on request of the Legal Aid Boards. It looked to the upcoming trends and expectations about the future. It was subject for further research and discussions.

2002: Advice report for Ministry of Committee of wise people in response to the report of 2001.

2004: Start of Legal Services Counters (Juridisch Loket). National network of counters for first line. Secondary line provided by lawyer, BAR members. LAAC’s dismantled.

2004: Extra payments for extra quality.

2005: Mediation as part of the legal aid services.

2006:Electronic connection with tax offices for eligibility check on income and assets.

2007: Announcement of reduction of the budget in the programme of the new government and start Rechtwijzer 1.0 as diagnosis and referral tool.

2008: Parliament didn’t agree with the reduction proposals. Again research where and how to reduce costs of legal aid.

2009: Elaboration of policy alternatives.

2010: Merge 5 LAB’s’ Introduction Hight Trust (HT).

2011: Introduction Diagnosis & Triage and Kenniswijzer.

2012: 5% reduction fees.

2013: Raise contribution clients. Start new duty solicitor’s scheme.

2015: Rechtwijzer online solution for separation/divorce.

2015: Rescheduling fees for criminal and restriction index fees.

2015: Report Committee Wolfsen; innovation legal aid system.

2016: Discussion about report Wolfsen.

2017: Report Committee van den Meer about fees.

2017-2019:

- Ongoing debates about the reform proposals.

- Debates about the fees for legal aid lawyers.

- Announcement of strikes of legal aid lawyers for duty solicitor’s scheme.

- Announcement by Minister of Justice: for the next two years extra budget of € 35 million.

Between 2003 and 2006 a major reform took place in the Dutch legal aid system. Legal Services Counters were set up to take over the primary (informative) function of the former Legal Aid and Advice Centres3; the secondary function (extended consultation and actual legal aid) was to be dealt with by private lawyers only. The goal of this operation was to keep the focus on primary legal aid and achieve more transparency of the legal aid system as a whole. The LAB set up the Legal Services Counters (LSC) as a separate body. The LSC are fully financed by the Board on the basis of a closed budget. The legal aid system operates according to an open end provision.

5.1.1. Recent developments following cutbacks in the system

Compared to 2000, public expenditure on legal aid was increasing over the years. Therefore, in 2008, the government decided to cut the budget for legal aid by 50 million euros, both in 2008 as well as in 2010. Several measures were implemented, like stimulating alternative ways of dispute settlement. Mediation and the ‘Roadmap to Justice’ (Rechtwijzer) were steps in that direction

The financial pressure on the system has increased even more due to the legal precedent that was set following the Salduz case. Following this judgment of the European Court in 2009, suspects will be entitled, prior to their questioning by the police, to consult a lawyer. Consultation and assistance during interrogation by a lawyer is free of charge in most cases, but as a result the own contributions clients have to pay were increased, with even higher adjustments in divorce cases in which the spouses did not choose to divorce via mediation.

In 2011, the State Secretary for Security and Justice announced that the system of legal aid needed to be reviewed in due course. Therefore a policy was developed that should result in structural savings of 85 million euros annually. Several measures took effect in 2015, like the temporarily reduction of the hourly legal aid rate paid to lawyers. However, most cutbacks have been suspended because the Senate filed a number of motions in 2015. A commission was established that issued an opinion after extensive research.

In November 2015 the Wolfsen Committee submitted a report to the Dutch Minister of Security and Justice entitled ‘Reassessing Legal Aid Towards a Durable System for Legal Aid’. The Wolfsen Committee suggested to organise the system in another way. These proposals focused on strengthening the first-line legal aid, increasing the quality of legal aid, a more bundled and multidisciplinary approach to legal problems, and investigating a possible increase in lawyers’ fees.

In a letter to the House of Representatives in November 2018, the Minister for Legal Protection described the outlines for a new system of legal aid. The outlines are mainly based on information that the Minister has gained during a number of design sessions in 2018 with organizations that play a role in and around the system of legal aid. When designing the outlines, the precondition was that a new system should not lead to higher costs.

The Minister describes in his letter five main outlines for a new legal aid system:

- More accessible advice and information must become available to everyone, regardless of income;

- More triage at the front, so that clarity is quickly established about the best solution route for the person seeking justice and whether or not a case is eligible for legal aid; the best solution route for the problem can also be a route without legal assistance;

- More control over costs and quality, through the introduction of legal aid packages that should lead to fewer legal proceedings before the courts and a solution to handling a problem for an integral price;

- A new arrangement of clients’ own contribution in the costs of subsidized legal aid, whereby the clients’ contribution will amount to a percentage of the costs of the legal aid package;

- Realization of a better compensation scheme for the hours worked by the lawyers, by reducing the number of certificates, with which the Minister wishes to meet the conclusion of the committee Van der Meer that the lawyers’ fees are currently below par.

In January 2019, the House of Representatives approved a phased elaboration of the outlines via experiments. The elaboration must ultimately be submitted to the House for approval through drafting of regulations.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

Under the European Convention on Human Rights and the Constitution of the Netherlands, each citizen of the Netherlands has the right to access courts, apply for legal advice and representation and, if means do not suffice, receive state-financed legal aid.[1] The right to legal aid is specified in section 18 of the Dutch constitution:

Everyone may be legally represented in legal and administrative proceedings. (2) Terms concerning the supply of legal aid to persons of limited means shall be laid down by Act of Parliament.

The Dutch Legal Aid system provides legal aid to people of limited means. Anyone in need of professional legal aid but unable to (fully) bear the costs, is entitled to call upon the provisions as set down in the Legal Aid Act (in force since 1994; the last amendment in the regulations took effect on February 1st, 2015). The Legal Aid Act of 1994 replaced the prior statutory system that dealt with the supply of legal aid and dates back as far as 1957.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

Residing under the competence of the Ministry of Justice & Security (J&S), an independent governing body called the Legal Aid Board (‘Raad voor Rechtsbijstand’, LAB) is entrusted with all matters concerning administration, organization, supervision and expenditure as well as with the actual implementation of the Legal Aid System. This includes matching the availability of legal experts with the demand for legal aid, as well as the supervision and quality control of the actual services provided. Regularly, figures are published that report on the previous years’ situation.

Board members are appointed by the Minister of Justice and Security for four years, with the possibility of an extra term. The CEO is overall responsible and is assisted by a board of four directors. The LAB has nearly 200 employees (full-time equivalent).

The LAB is set up as an independent organization, accountable but not subordinated to the Ministry of Justice & Security. To ensure independence, it is necessary that the person who decides whether or not to grant subsidized legal aid has no interest in the outcome of the case and has no interest in referring the case to a legal aid provider. That independence is guaranteed through the Legal Aid Act.

The main strategy of the LAB in the past ten years has been to strengthen zero (Rechtwijzer) and first line legal aid (LSC) and to raise quality standards. Also the LAB has reduced its own costs by introducing web-based platforms for the handling of requests for legal aid. More and more requests are tested on basis of random test controls (High Trust system).

Rechtwijzer was developed together with client-panels.

5.3.1. Threefold model

The Dutch legal aid system is basically a threefold model in that it encompasses three ‘lines’ that provide legal aid (see chart 2 below for a schematic representation). The legal aid system, therefore, is a mixed model, consisting of a public preliminary provision, public first-line and private second-line help.

- Online self-help, information and support is offered on the Rechtwijzer website (Rechtwijzer translates into Roadmap to Justice)[2]. Rechtwijzer is a preliminary provision and offers interactive ‘decision trees’ helping people to assess their situation. In addition, Rechtwijzer provides easy-to-understand information and guidance on possible solutions for the most common legal problems. Rechtwijzer combines publicly run guided pathways for common legal problems with online products and services from private service providers. The Legal Services Counters also have a website that can be seen as a preliminary provision.

- The Legal Services Counters act as what is commonly known as the ‘front office’ (primary help). Legal matters are being clarified to clients and information and advice given. Clients may be referred to a private lawyer or mediator, who act as the secondary line of legal aid. Clients may also apply for help from a subsidised lawyer or mediator directly. If necessary, clients can also be referred to other professionals or support agencies

- Private lawyers and mediators provide legal aid in more complicated or time-consuming matters (secondary help) in the form of certificates. A lawyer (or mediator) submits an application to the LAB on behalf of his client. If legal aid is granted, a certificate is issued which allows the lawyer in question to deal with the case. Lawyers and mediators are paid by the LAB to provide their services to clients of limited means. Generally they are paid a fixed fee according to the type of case, although exceptions can be made for more time consuming cases.

To some extent, trade unions and consumer organisations also provide legal aid. The number of legal aid insurance policies continued to rise for a long time and has stabilized around 42% of the Dutch households since 2010.

5.4. Legal aid budget

Being financed by the Ministry of J&S, the Legal Aid Board (LAB) accounts to this ministry for its budgetary allocations. The legal aid system operates according to an open end provision. Since the beginning of the system in 1994, spending on legal aid more than doubled in 2012. However, the upward trend then came to an end and since 2014 it decreases (see table below).[3]

| Dutch population and expenditure on legal aid

* in thousands |

|||||||||

| 1994 | 1998 | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | |

| Total Dutch population* | 15,300 | 15,650 | 16,105 | 16,334 | 16,575 | 16,656 | 16,829 | 16,979 | 17,181 |

| Total expenditure on legal aid in Euro | 184,000 | 195,000 | 315,000 | 398,000 | 472,000 | 486,000 | 432,000 | 432,000 | 395,000 |

| Expenditure per capita in Euro | 12 | 12 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 29 | 26 | 25 | 23 |

Given their financial means, approximately 37% of the Dutch population (with a total of 17 million people) would, according to the latest estimates, qualify for secondary legal aid if circumstances so require. The legal aid itself is mainly financed by the state (the Legal Aid Fund) and only for a minor part by an income-related contribution of the individual client.

Sometimes clients are exempted from individual contributions. This applies to all cases where people have been deprived of their freedom against their will. ‘Have-nots’ are also exempted from paying an individual contribution as well as victims of violent crime and sexual offenses.

In civil cases legal aided litigants who lose their case can be held responsible to pay the other side’s legal expenses/ costs. In criminal cases convicts (when irrevocably convicted) are obliged to pay back the legal aid they received when they in hindsight appear not to be eligible for legal aid.

5.5. Legal aid providers

Legal aid providers (lawyers and mediators) receive compensation for the assistance they provide on the basis of a system of points, where one point corresponds to one hour.[4] The various forms of legal assistance have been divided into 177 different types of cases, whereby each case type has been given a code. A fixed number of points has been allocated to each case code. This number of points has been determined on the basis of the average time spent on such cases. Total compensation is calculated by multiplying the number of points per case by a standard amount.

The current allocation of points per case is based on the average time expenditure on such cases, found in a study of the Maan commission, conducted more than twenty years ago.

The “Commissie evaluatie puntentoekenning gesubsidieerde rechtsbijstand”, chaired by Mr. H. Th. Van der Meer, was established, to evaluate the point allocation system. The evaluation showed that for most of these case codes (79%) the current average time expenditure exceeds the number of points allocated to those cases. In a single case, the average time expenditure exceeds the number of points allocated by a factor of two. On average, the amount of time spent is 2.9 hours higher than the points received.

According to the Van der Meer commission, the actual hourly rate for social lawyers is currently slightly more than 75 euros on average, given the current amount of work. That is low, because this roughly corresponds to a net income between the maximum of scale 8 and of scale 9 for civil servants at 1,200 chargeable hours of work, which should be the level of scale 11 or 12. With the development of a new system, the Minister of Justice expects to make a first step towards better compensation for hours worked. The extent to which the rates can rise depends on the extent to which the new system will develop and the volume of the number of certificates will fall.

In order to make legal aid possible for their clients, lawyers have, among other things, a legal duty of confidentiality (section 10a of the Act of Advocates). What a person entrusts to his lawyer, just like what a person discusses with his doctor, must remain secret. The right to refuse to give evidence is necessary in order to guarantee the confidential communication to which the citizen is entitled and in this sense complements the duty of confidentiality. The right to refuse to give evidence means that a lawyer does not have to share confidential information

5.6 Quality assurance

Legal aid in the Netherlands is usually provided by private lawyers/ law firms that provide legal advice and represent clients in cases that deal with the major fields of legal aid: criminal, family, labour / employment, housing, social security, consumer, administrative, asylum and immigration. To be entitled to accept legal aid cases, private lawyers need to be registered by the LAB and to comply with a set of quality standards. These standards are set by the Bar. For some fields of law – criminal, victims of crime, mental health, asylum and immigration law, youth, family law, labour law, social security law and rental cases – additional terms apply. The lawyer must both have adequate expertise and sufficient experience in that particular field. Also, a permanent education system exists, in which lawyers have to earn a certain amount of study/training-points every year in order to keep being trained constantly.

In the Netherlands, the role of the deans of the local bar associations is to cooperate with all institutions which helps to improve the communication in the whole system and to reveal problems in a cooperative and in an informal manner. The deans of the local bar associations collect all complaints.[5]

Lawyers conduct customer satisfaction surveys themselves. Also, the LAB conducts such surveys regularly. The most recent survey took place in 2017, it showed that clients are satisfied with their lawyer in general.

To judge whether lawyers do a good job legally, the LAB has asked other legal professionals (judges, prosecutors) to judge the work of lawyers. This research shows that other legal professionals judge lawyers’ work mostly positive, although it varies.

In the Netherlands, peer review is (only) established in the area of asylum law. In this field of law lawyers came to the agreement that clients are highly vulnerable and have little possibilities to complain if they were dissatisfied with the quality of the legal aid service by the lawyer as they are typically sent back to their home country after their application for asylum is refused. All lawyers decided on the implementation of the peer review system in a democratic vote and they also elect the peers who conduct the peer review; in order to do that the peers review the files of the lawyers regularly, attends court sessions and monitors new asylum lawyers.

5.7. Criminal legal aid

5.7.1 Scope of criminal legal aid

Following Salduz judgment (2009) of the European Court of Human Rights, suspects are entitled, prior to their questioning by the police, to consult a lawyer for ¾ hour. This may, if needed, be extended by another ¾ hour.

For such and similar cases the need to fill in a request to obtain a certificate for subsidized legal aid does not really work. Thus, besides certificates, the LAB also provides duty lawyers. Each criminal suspect, alien or psychiatric patient who has been lawfully deprived of his liberty against his will is visited by a legal aid lawyer. The lawyer can also attend the police-interrogations. A lawyer can do the following things for the suspect before his interrogation:

- Explain the offence he is suspected of committing.

- Give legal advice.

- Tell the suspect what is involved in a police interrogation.

- Tell the suspect what rights and obligations he has during the interrogation.

- Contact the family or employer to inform them of his situation (if this is what he wants).

A lawyer can do the following for the suspect during the interrogation:

- The lawyer may ask questions and make comments to the interrogating officer at the beginning and end of the interrogation.

- In the course of the interview the suspect or his lawyer may ask for a pause to consult one another. If this occurs too often, the interrogating officer may refuse this.

- If the suspect does not understand questions or remarks, if the suspect is placed under improper pressure, or if he is unable to be questioned further because of his state of health, the lawyer has the right to draw this to the attention of the interrogator.

- When it is over the suspect and his lawyer have the right examine the official report of the interrogation (the proces-verbaal) and point out any inaccuracies it may contain.

After the suspect has been interrogated, the case may be settled in a number of different ways:

A. Dismissal

The case may be (provisionally) dismissed. In that case the suspect will not be prosecuted. Conditions may be attached to the decision to dismiss the case however, which the suspect must comply with. Such as a ban on contact with the victim, and/or probation supervision with special conditions. What happens if the suspect fail to comply with these conditions? Or if the suspect commits another criminal offence? In that case the suspect could still be summoned in relation to the matter in question. Which means the suspect would have to appear in court after all.

B. Penalty order issued by the public prosecutor

If the public prosecutor is of the opinion that the suspect is guilty he may impose a penalty order on the suspect. A penalty order may involve a fine or a community punishment order for example. Or a disqualification from driving (the person is not allowed to drive any vehicles) and/or a behavioral intervention (such as a ban on contact with certain persons, or compulsory contact with the probation service).

Does the suspect wants to settle his case immediately? In that case the person can pay the fine directly at the police station. This is only possible if the suspect was able to consult a lawyer in advance. Can the person pay immediately? In that event the case is definitively settled. This will mean that the person can no longer object to (resist) the penalty order.

If the public prosecutor decides to impose a driving ban or community punishment order, the person will be questioned about the matter first. The person may consult a lawyer prior to this hearing. The lawyer is also permitted to be present during this hearing.

If the suspect wants his lawyer to be present at the hearing, the hearing will be held at another time if necessary. A video connection may also be used to conduct the hearing.

C. Out-of-court settlement

The public prosecutor may also offer the suspect an out-of-court settlement. This means certain conditions will be imposed on the person. If the person complies with these conditions the person will avoid further prosecution. The most important of these conditions are: payment of a sum of money, a compensation payment for the victim or the relinquishment of seized property. If the person does not comply or does not comply in time with these conditions the person will have to appear in court. In certain circumstances the person can also pay an out-of-court settlement immediately, if the person has no fixed place of abode or residence in the Netherlands for example.

D. Court

A case may also be brought before the court. In that case the suspect will receive a summons. The summons will state the offence he is accused of committing and the date, time and place at which the criminal case will be tried.

If the suspect decides to accept a penalty order issued by a public prosecutor or accepts an out-of-court settlement proposal from the public prosecutor, an entry will be made in the judicial records (criminal record). This may mean that the suspect can no longer obtain the certificate of good conduct (VOG) needed for a new job or work experience placement.

If the suspect is between 12 and 18 years old and suspected of committing a criminal offence, then the police engages a lawyer to advice the minor before the interrogation begins. In case of a minor, the lawyer also has the right to be present during the interrogation.

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

If the suspect has committed an extremely serious offence with a penalty of 12 years or more (involving murder or manslaughter for example) or the suspect is minor or considered vulnerable by the police in view of his mental condition, then a lawyer will always be provided before the suspect is interrogated. This will not cost the suspect anything. When the suspect does not require a consultation with a lawyer, he needs to clearly express this to the lawyer. A minor or a vulnerable person cannot refuse legal aid.

If the suspect is suspected of committing a serious offence (offences for which you can also be detained before trial, such as burglary) he may choose to speak to a lawyer before the interrogation. The police will then see to it that a lawyer is engaged. This will not cost the suspect anything.

If the suspect is suspected of committing a less serious offence, he may decide for himself whether he wants to speak to a lawyer. In that case he must find his own lawyer and he will have to pay the cost thereof himself.

The suspect also has the right to have a lawyer present to assist him during the interrogation. If he is suspected of committing a serious offence, this will not cost him anything. If the suspect is suspected of committing a less serious offence, he will have to pay these costs himself.

If the suspect has a preferred lawyer and this lawyer is not registered with the Legal Aid Board, then the suspect has to pay the costs of the lawyer himself.

5.7.3. Process for obtaining criminal legal aid

The central unit for processing applications from the police is set up at the LAB office in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. This duty lawyer department is responsible for preparing duty lawyer service schedules and providing them to participating lawyers. The processing and monitoring of applications from the police is also one of the tasks of this unit. The unit acts as a helpdesk.

To guarantee that legal aid is provided in time, the map of the Netherlands is divided into regions for which duty solicitor schedules are drawn up. There are 37 regions for adults and 33 regions for minors. These regions must not be too large in connection with the distances to be travelled by lawyers. A duty solicitor schedule designates 1 to 7 lawyers daily, depending on the scale of crime in the region, to accept cases on a daily basis between 7.00 a.m. and 8.00 p.m. In the busiest regions the services of lawyers are sometimes divided between an early shift and a late shift.

When legal aid has to be requested for an arrested suspect this is registered by the police in its own system. That computer system can then automatically send a notification to a web-server of the LAB. That electronic notification will also include details of the case from the police. What kind of offence is involved? Does the suspect have a preference for a particular lawyer? Is the suspect addicted, does he need an interpreter, for what language, etc?

The computer system will pass the application or notification on to the lawyer on duty according to the duty solicitor schedule or to the preferred lawyer of the suspect. The lawyer receives the notification by email. In practice the lawyer will probably read the notification on his smart phone. He has 45 minutes in which to accept the notification by ‘pressing the button’. A preferred lawyer is engaged in about 25% of cases.

When a notification is not accepted it is passed on to by the computer to the next lawyer in line. This process makes the previous telephone and fax traffic largely redundant.

If a notification fails to be accepted twice, it will be taken up by the LAB duty lawyer department. A member of staff will then proceed to look for a lawyer by telephone.

When a citizen is held in custody during legal proceedings he will get legal aid without costs on decision of the court (mandatory). Citizens who are not detained have to apply for legal aid by themselves and the LAB will conduct a means and merits test.

5.8. Civil legal aid

5.8.1. Scope of civil legal aid

The scope of legal aid is not limited to certain cases. Legal aid can be granted for all kinds of problems, except small claims under € 500[6] and company problems. The problem should be related to the Dutch legal sphere.

EU-rulings assure that a resident of another EU-country can be assisted in case of a problem handled before a Dutch tribunal.

5.8.2. Eligibility criteria for civil legal aid

A. Eligibility

Given their financial means, approximately 37% of the Dutch population (with a total of 17 million people) would, according to the latest estimates, qualify for legal aid if circumstances so require. The legal aid itself is mainly financed by the state (the Legal Aid Fund) and only for a minor part by an income-related contribution of the individual client.

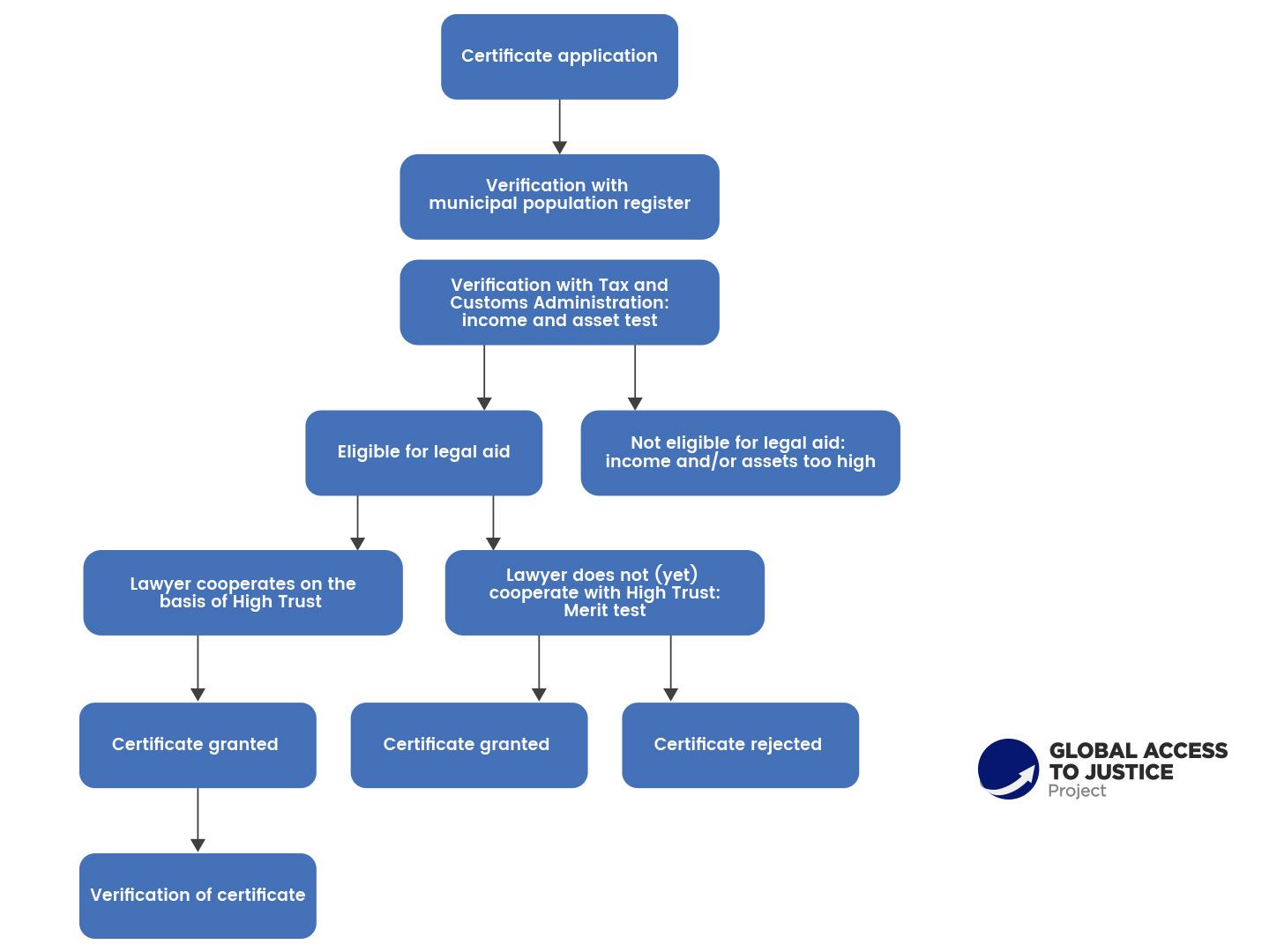

The eligibility for legal aid is based on both the client’s annual income and his assets. The LAB verifies the client’s personal data with those in the municipal population register and checks the applicant’s income and assets with the tax authorities. It is able to do so with the aid of a ‘burgerservicenummer’ (citizen service number) (BSN); this is a unique identification number, which every Dutch citizen receives when registering in the municipal population register. Thanks to online connections with the tax authorities, the Legal Aid Board is able to rapidly obtain information concerning the applicant’s income and assets.

Additionally, also non-Dutch litigants receive legal aid when they have a problem that concerns the Dutch legal system.

Assessment of the applicant’s income and assets level (and hence his eligibility for legal aid) is based on his situation two years prior to the application date, the so-called reference year (t-2). The reason to use that year’s data, is that those data have generally been found correct and therefore final. So, for a certificate to be granted in 2018, the applicant’s income in 2016 is decisive. In order to qualify for legal aid in 2018, the applicant’s income in 2016 should not be higher than € 26,900 (single person) or € 38,000 (married persons / single person with children). The applicant’s assets must not exceed € 24,437.[7]

However, requests can be made to change the reference year, if the applicant’s income and/or assets in the year of application has decreased substantially compared to that in the reference year. This holds if the applicant’s reference-year income and/or assets would not make him eligible for legal aid, whereas his present income and/or assets will. If an applicant wishes to be eligible for a lower contribution, his income needs to have decreased by at least 15% compared to the reference year.[8]

When a client receives a certain sum of money because of the result of a procedure, his certificate will be withdrawn retroactively. He will be expected to pay his own lawyer.

B. Client’s contributions and the ‘diagnosis and triage’ procedure

The costs of legal aid are not only paid by the LAB, but are partly covered by a contribution from the client himself. This personal contribution, though often covering only a small part of the actual expenses, is meant to incite clients to carefully weigh the pros and cons of taking a matter to a lawyer, and hence discouraging frivolous cases so as to remain in better control of the costs of the legal aid system at large.

In July 2011, the ‘diagnosis and triage’ procedure was implemented. The procedure encourages those seeking justice to first submit their problem or dispute to the Legal Services Counter. It was expected that it would be possible to solve more legal issues and problems at an early stage or via a different channel if they are first submitted to the Legal Services Counter. As a result, the number of future applications for certificates was expected to drop.

People seeking justice are encouraged to visit the Legal Services Counter before approaching a lawyer by offering them a discount of € 53 on the individual contribution, should it turn out that a certificate is needed after all.[9]