National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

The Republic of Kenya is a democratic and unitary State with two spheres of government: national and county. In this regard, the country is run by the National Government and 47 county governments. The two levels of government work in close consultation as espoused in Article 6 (2) of the Constitution of Kenya,[1] with their distinct functions outlined under the Fourth Schedule of the Constitution. The exercise of power is both horizontal and vertical. The horizontal one is distributed between executive, legislature and judiciary, and the vertical one has power devolved to the 47 geographical sub-regions – the counties.

According to the data emanating for the 2019 census exercise carried out by the Kenya National Registration Bureau, the total population in Kenya stands at 47,564,296, of which 23,548,056 are Males, 24,014,716 are Females and 1,524 are Intersex.[2] African peoples indigenous to Kenya, who now form 98% of the population, fall into three major cultural and linguistic groups: Bantu, Nilotic, and Cushitic, with over 70% of the population being Bantu. The estimated proportions of the major groups are Kikuyu 22%, Luhya 14%, Luo 13%, Kalenjin 12%, Kamba 11%, Kisii 6%, and Meru 6%. Other Africans constitute 15% of the total population.[3] The national language of the Republic of Kenya is Kiswahili while the official languages are Kiswahili and English.[4] According to Article 8 of the 2010 Constitution, there is no state religion in the Republic of Kenya. Approximately 83 percent of the population is Christian, 11 percent Muslim, 2% constitute Hindus, Sikhs, and Baha’is while the remaining 4-5 percent of the population adheres to various traditional religious beliefs.[5]

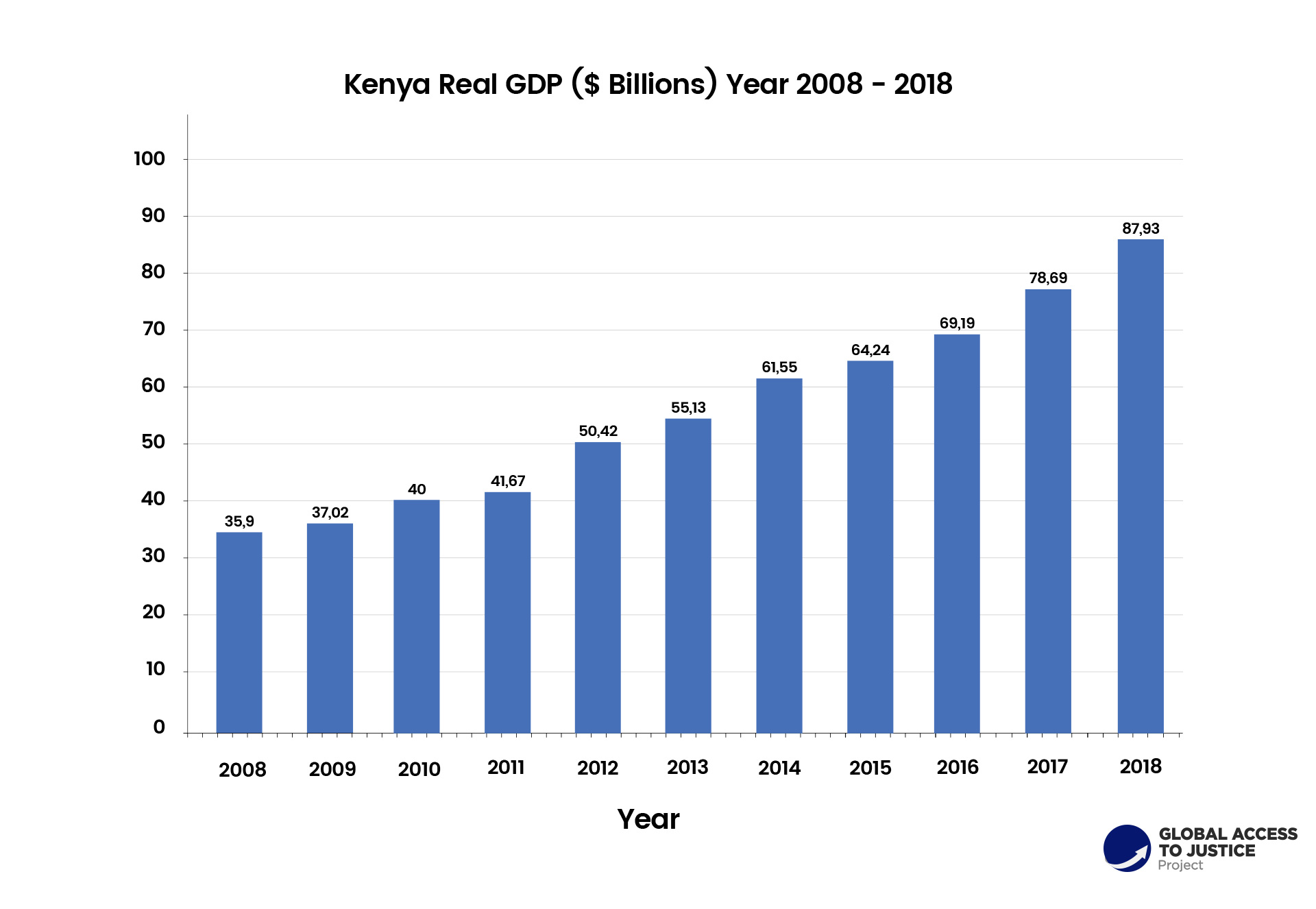

Chart 1. Kenya’s GDP for the last ten years

Kenya’s Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2017 is 0.590 – which put the country in the medium human development category – positioning it at 142 out of 189 countries and territories. Kenya’s life expectancy at birth is 67.3 years which is an increase of 9.8 years between 1990 and 2017. The expected years of schooling stand at 12.1 years while the gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP) is $2,961.[6]

Kenya’s Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2017 is 0.590 – which put the country in the medium human development category – positioning it at 142 out of 189 countries and territories. Kenya’s life expectancy at birth is 67.3 years which is an increase of 9.8 years between 1990 and 2017. The expected years of schooling stand at 12.1 years while the gross national income at purchasing power parity per capita GNI (PPP) is $2,961.[6]

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Type of legal system

Kenya’s legal system is based on statutory law, English common law, customary law, and Islamic law. It has evolved from the inheritance of its English Common Law tradition to modern day system adapting to the changing social, economic and political trends.

2.2. Organization of the justice system

The Judiciary forms one of the three State organs established under Chapter 10, Article 159 of the Constitution of Kenya,[1] as an independent custodian of justice in the country. The Judiciary of Kenya’s mission is to administer justice in a fair, timely, accountable and accessible manner, uphold the rule of law, advance indigenous jurisprudence and protect the constitution. Its primary role is to exercise judicial authority given to it, by the people of Kenya.

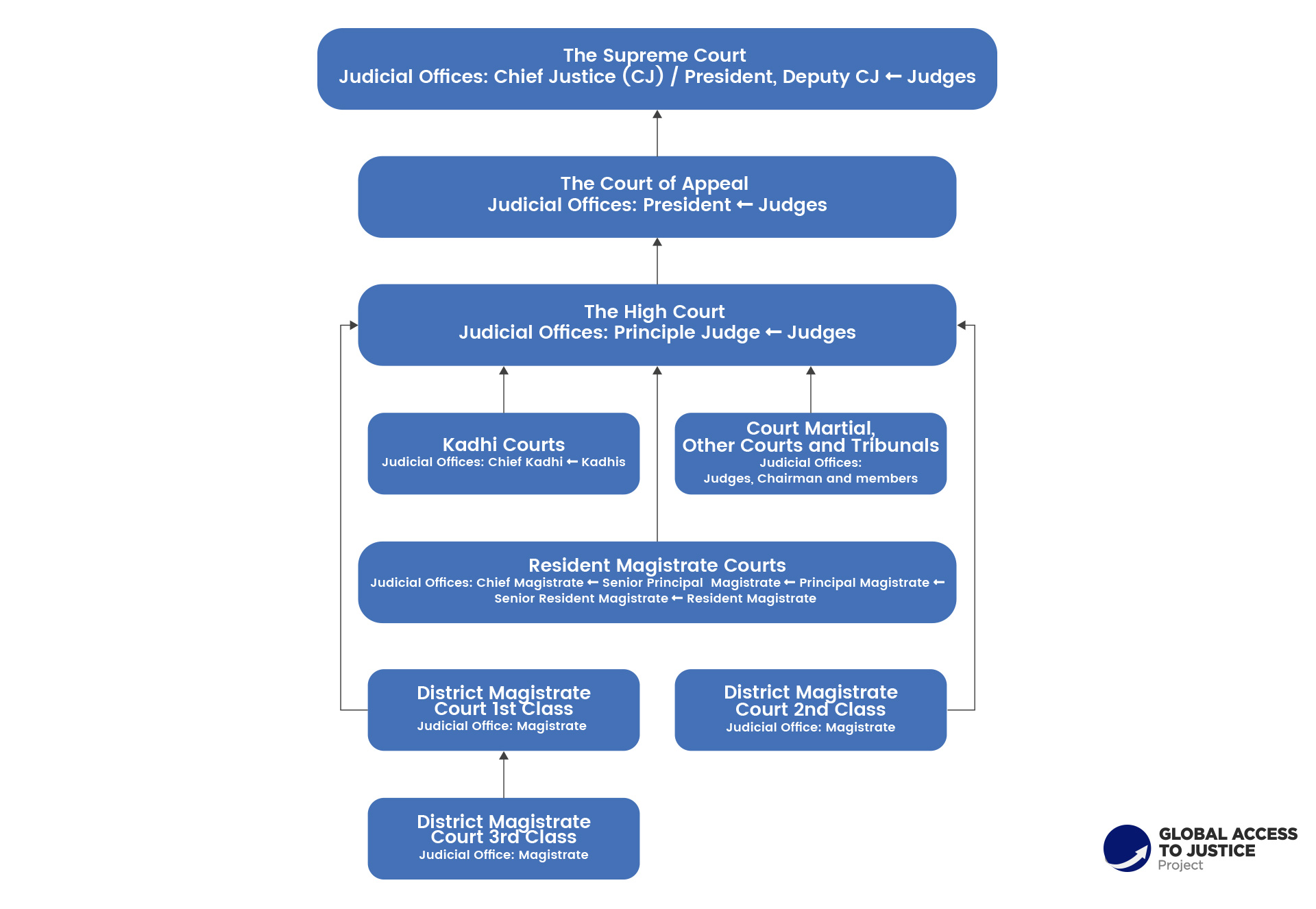

In Kenya, the courts under the Constitution operate at two levels, namely: Superior and Subordinate courts. The Court system has been decentralized with the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal having their own Presidents and the High Court having a Principal Judge serving as heads of the respective institutions. The Supreme Court is established under Article 163 of the Constitution of Kenya and it comprises of Seven judges namely: the Chief Justice, who is the president of the Court, the Deputy Chief Justice, who is the deputy to the Chief Justice and the vice-president of the Supreme Court and five other judges. The Court of Appeal is established under Article 164 of the Constitution of Kenya 2010. The High Court is established under Article 165 and it comprises a maximum of 150 judges and has original jurisdiction in all criminal and civil matters.[2] The Court has a Principal Judge, who is elected by the judges of the High Court from among themselves. The High Court is a premier court in interpreting the Constitution, hears appeals from subordinate courts and tribunals and supervises all administrative bodies (judicial review). The High Court has also been restructured into seven divisions: Family, Commercial and Admiralty, Constitutional and Judicial Review, Land and Environment, Criminal, Industrial and Environmental and Land Court. There are at least 20 High Court stations countrywide.

The subordinate courts are established under Article 169. They consist of the Magistrates’ Courts, Kadhis Courts, Court Martial, and any other court or local Tribunal[3] established by an Act of Parliament.

In addition to the above judicial forums for adjudication of disputes, the Constitution of Kenya also provides for Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms which are anchored in the law. In this regard, Article 159 of the Constitution stipulates that in exercise of judicial authority, courts and tribunals are to promote alternative forms of dispute resolution including reconciliation, mediation, arbitration and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms. ADR mechanisms including negotiation, mediation and arbitration are also available in the settlement of intergovernmental disputes.[4]

Chart 2. Structure of the Judiciary in Kenya

2.3. The structure of legal professions

The legal profession in Kenya is governed by a regulatory framework comprising statutory provisions, a series of subordinate legislation, a Digest of Professional Conduct and Etiquette and a number of guidance documents issued by the Law Society of Kenya as the regulatory body. The Law Society of Kenya is a professional statutory body drawing membership of all advocates currently totaling over 15,000.[5]

Kenya’s Constitution proclaims that “the State shall ensure access to justice for all persons and, if any fee is required, it shall be reasonable and shall not impede access to justice.”[6] The Constitution also provides that every person “has the right to have any dispute that can be resolved by the application of law decided in a fair and public hearing before a court or, if appropriate, another independent and impartial tribunal or body.”[7] Despite this constitutionally mandated right to equal access to justice, many Kenyans cannot access the country’s justice system because they are unaware of their basic rights, the courts are structured in a way that does not facilitate equal access to all, and legal services are unaffordable to most of the country’s population.[8]

The law in Kenya defines a paralegal to mean a person employed by the Service or an accredited legal aid provider who has completed a training course in the relevant field of study in an institution approved by the Council of Legal Education.[9] The Act goes ahead to define an accredited paralegal as, “a person accredited by the service to provide paralegal services under the supervision of an advocate or an accredited legal aid provider”. Thus a person shall only provide paralegal services unless he/she is accredited by the Board. Paralegals may be employed as assistants to lawyers, or do other limited but lawyer-like work. There is a paralegal movement aimed at providing legal advice, assistance and support services that are relevant and practical especially in remote or otherwise marginalised areas (like slums) that have high levels of indigent, legally unsophisticated and vulnerable populations. These paralegals usually provide their services for free.[10]

There are more than 3,000 paralegals in Kenya working in the community, prisons, police stations, courts and other state, private and civil society agencies – a remarkable figure when you consider the number of lawyers supposed to be in practice (according to the Law Society, about 6,500).[11] Paralegals work closely with chiefs, police officers, probation officers, children officers, prison officers, lawyers and land officers, among others. They may assist in developing legal awareness, giving legal advice, being intermediaries and accompanying complainants or accused persons to police stations or court, drafting simple court or legal documents, watchdog advocacy on land and human rights abuses, counseling and referring matters to relevant agencies including, if necessary, lawyers.

The judiciary is primarily charged with the responsibility of ensuring that there is fair and effective administration of justice. Consequently, it also provides a safeguard against the abuse of power by the Executive, and in certain circumstances the Legislature; this is in accordance with the principles of the doctrine of separation of powers.[12] The judiciary, in relations to the principle of checks and balances has the sole mandate of ensuring that the other arms of government act within the Constitution. It has both institutional and financial independence. Separation of Powers is a fundamental doctrine from which the principle of judicial independence is rooted. The doctrine of the separation of power is distinctively highlighted in the constitution, 2010.[13]

One of the critical issues for judicial reforms intended to be resolved by the Constitution of Kenya 2010 was the need to have a more independent, transparent and accountable judiciary.[14] The New Constitution attempts to address this concern by creating a more inclusive and accountable Judicial Service Commission as an independent mechanism for appointment of judges. According to article 171 of the 2010 Constitution, other than the Chief Justice, the Attorney General and representatives of each of the superior courts, the Judicial Service Commission is equally representative of magistrates, statutory body that regulates advocates, Public Service Commission and lay persons. Whereas the President appoints the representatives of the lay persons, such appointments must be approved by the National Assembly.[15] Judges enjoy security of tenure,[16] have their salaries charged on the Consolidated Fund,[17] cannot have their salaries and benefits varied to their disadvantage[18] and are immune from any action or suit in respect of anything done in good faith in exercise of their judicial function.[19] Critics however still argue that the safeguards given to judges to ensure independence of the judiciary should extend to the magistrates.[20] According to the Constitution of Kenya, a judge shall retire from office on attaining the age of seventy years, but may elect to retire at any time after attaining the age of sixty-five years.[21]

According to the Judiciary and the Administration of Justice Report (SOJAR), the Judiciary had of 5,698 employees as at the end of the 2017-2018 reporting period. The Judiciary is composed of 155 Judges (2.8 per cent); 513 Magistrates and Kadhis (9.2 per cent) and 4,930 (88.1 per cent) Judicial Staff. There are 2,728 female employees representing 48.7 % and 2,870 are male, representing 51.3% of the Judiciary workforce. 91 members of staff are Persons living with Disabilities (PWDs), representing 1.6 per cent of the Judiciary workforce.[22]

The 2010 Constitution also establishes the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions in Kenya. The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) is the National Prosecuting Authority in Kenya. The Constitution mandates it to prosecute all criminal cases in the country. The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) is the head of the ODPP and operates independently according to Article 157 of the Constitution. The Director of Public Prosecutions shall hold office for a term of eight years and shall not be eligible for re-appointment.[23]

The DPP is accountable to the Public by presenting an annual report to Parliament and the President on the performance of the ODPP. The DPP may also be required, on a need basis to present a report to Parliament on a matter of national or public interest. The Office delinked from the Attorney General’s Office in 2011 after the promulgation of the Constitution in 2010. The ODPP has a presence in all the 47 counties in Kenya with its headquarters in the City of Nairobi. A Chief County Prosecutor (CCP) heads each ODPP County Office. He or she is responsible for working with the courts and the investigative agencies. The DPP helps these bodies to provide high-quality prosecution services in their jurisdiction.

Nationally, the ODPP prosecutors deal with a wide range of cases. They range from minor offences in the magistrates’ courts to serious cases such as murder in the High Court. The majority of the workload is in the Magistrates’ Courts.

In conclusion, it is noteworthy to note that the 2010 Constitution was promulgated to meet multiple ambitions, including guaranteeing the citizenry right to access to justice. This notwithstanding, many Kenyans, especially from undeserved communities lack the capacity and access to enjoy their constitutional right of access to justice. This is majorly occasioned by a myriad of economic, structural, and institutional factors including financial constraints, complexity in both substantial and procedural law, time, and geographical and physical constraints.

PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

Kenya’s criminal justice system involves various actors with defined duties and responsibilities in managing offenders. Key players in the criminal justice system in Kenya are the police (investigation and arrest); the judiciary (the court process); the probation after care services and the prison services (rehabilitation, reformation and reintegration). The police play a critical role as the point of entry – for every offender – to the criminal justice system. They receive and record complaints, arrest suspects/ accused persons, investigate cases and most importantly draw up the charge sheet.

The right not to have one’s freedom curtailed without a justifiable case is guaranteed by Article 29 (a) of the Constitution, which provides that every person shall have the right to freedom and security and shall not be deprived of freedom arbitrarily and without just cause. Since an arrest amounts to a curtailment of a person’s freedom, a lawful arrest is that which is founded on a justifiable cause. An arrest is lawful if it is made pursuant to a valid arrest warrant. For a warrant of arrest to be lawful, it must conform to the standards set forth under the law. In Kenya, the law governing the form, content and manner of execution of a valid warrant are to be found in Section 102 through to Section 109 of the CPC.

An arrest without a warrant is allowable only on grounds listed in the CPC. Instances when a police officer, a private person or a magistrate may make an arrest are outlined in Section 29. In the exercise of the power to make an arrest, the use of violence by both public and private sources is prohibited, Article 29(c) of the Constitution. Further, the CPC allows the use of only that amount of restraint that is necessary to prevent escape (Section 24). Thus, the validity of an arrest without a warrant may be challenged if the ground for arrest falls outside those expressly listed in the CPC or if the arrest is effected by the application of unjustifiable force.

3.2. Civil Procedure

Civil suits are court cases between two or more individuals, private entities or public entities that are privately prosecuted. In civil cases the individual suing prosecutes the case and caters for the cost of prosecution unlike in criminal cases where the state is the prosecuting party. The Plaintiff is the person/entity suing while the Defendant is the person/entity being sued. Examples of civil claims include defamation claims, breach of contract, negligence, assault, battery and fraud.

Below is a summary of the civil procedure in Kenya:

3.2.1. Client Interview

Predominantly, it is important to note that the civil procedure process in Kenya commences at the client interview stage whose purpose and scope is to form an advocate-client relationship, learn the client’s goals, learn as much as the client knows about the facts of the issue and reduce the client’s anxiety without being unrealistic.

3.2.2. Pre-trial Preliminary Considerations

It is noteworthy, that under this banner, a cause of action is determined by examining both the law and facts of the case. Identifying the elements of a cause of action is important in the litigation process for various reasons. Most important is that each of the elements must be proven at trial for the plaintiff to prevail and besides, the initial pleadings must allege facts that support each element of the cause of action.

3.2.3. The Demand Letter

Once a cause of action is ascertained, the next step is to write up the demand letter. A demand letter is a formal notice demanding that the addressee perform a legal obligation, such as rectifying a problem, paying a sum of money or honouring a contractual commitment, on specific terms and within a specified time. The letter gives the recipient a chance to perform the obligation without being taken to court. In certain types of legal proceedings, a demand letter is mandatory and where it is pleaded, a demand is required to be made as a matter of law. It is central to posit that the demand letter is sent before the commencement of the suit and the adversary is given a time-frame within which a response is required. The demand letter has now become a compulsory document within the Civil Procedure Rules, 2010 according to Order 3 rule 2(d).

3.2.4. How to approach the Court

A. Originating an Action

Legal proceedings are commenced when a plaintiff makes a complaint or demand before a court in due form. Every pleading in civil proceedings shall contain information as to the circumstances in which it is alleged that the liability has arisen (Order 2 Rule1). Pleadings are written statements of parties to a suit, which are served, on each party. Normally this statement of pleadings sets in summary form the nature of the case and the material facts that support the claim. Legal proceedings can be commenced by way of Plaint, Originating summons, Notice of motion, Chamber summons, etc.

B. Filing of documents

Order 3 Rule 3 posits that a register of suits, to be called the register of civil suits, shall be kept at every registry. The particulars of every suit filed in a registry shall be entered in the register. Further every plaint (with all the supporting documents i.e. list of witnesses and witness statements, list and bundle of documents including the demand letter) to be filed shall be presented to the registry during office hours together with any fee payable on its filing and each such plaint shall be date-stamped with the date on which it was so presented which shall be the date of filing the suit notwithstanding any dispute as to the amount of the fee payable. Any other document that a party may wish to file in the course of the proceedings after pleadings have been closed may be filed with the leave of the court.]

C. The Plaint in General

The plaint is the pleading in which the plaintiff states the basis of the lawsuit. It is the most widely used pleading in commencing civil suits. Generally, the plaint identifies the plaintiff(s) and defendant(s) in the lawsuit, and describes their status and capacity to sue and be sued, describes the factual basis for the lawsuit, makes a request or demand for some relief from the court and contains a statement showing that the court in which it is filed has the proper jurisdiction and venue.

D. Issue and Service of Summons (Order 5 Rule 1)

It is imperative to note that upon filing the suit, summons shall issue to the defendant to appear and answer in court. The summons shall be prepared by the plaintiff or his advocate and filed with a copy of the plaint. It is a mandatory requirement that the summons shall be signed and sealed with the seal of the court by a judge or an officer designated by him within 30 days from date of filing. Cognisance shall be had of the defendant’s place of residence to allow him to make an appearance. However, the period shall not be less than 10 days. The summons shall be collected for service within 30 days of issue or of notice of issue and are valid for 12 months. Do note that where the summons have not been served on the defendant, the court may extend the validity of such summons from time to time if it deems just to do so. An application for extension of validity of summons shall be made by filing an affidavit of service indicating how many attempts have been made at service and their results. If no application is made for extension of validity of summons, the court may without notice dismiss the suit upon expiry of 24 months from date of issue of original summons. It is important to note down that the serving officer in all cases in which summons has been served shall swear and annex to the original summons an affidavit of service stating the time when and the manner in which summons was served and the name and address of the person served and witnessing the delivery of summons (See Order 5 Rule 15).

E. Responding to Pleadings

(i) Written Statement of Defense

The written statement of the defense is a pleading presented by the defendant intended to traverse the allegations on the plaint. The function of a written statement of defense is to state the grounds and the material facts on which the defendant relies for his defence and also is to inform the plaintiff precisely how much of the statement of the claim the defendant relies on to defeat the claim of the plaintiff.

(ii) Striking out Pleadings (Order 2 Rule 15)

The court may at any stage of the proceedings order to be struck out or amended any pleadings in an action or anything in any pleading on the grounds that it discloses no reasonable cause of action or defence, it is scandalous, frivolous and vexatious, it may prejudice, embarrass, or delay fair trial or it is an abuse of the process of the court.

(iii) Third Party Notice (Order 1 Rule 15)

Where the defendant claims against another party not already a party to the suit that he is entitled to contribution or indemnity from him, that he is entitled to a relief or remedy relating to or connected to the original suit and therefore the same as some of the relief or remedy claimed by the plaintiff or that the question or issue relating to or connected to the subject matter of the suit is essentially the same question or issue arising between the plaintiff and the defendant and should properly be determined as between plaintiff , defendant and third party, or any or either of them He shall apply to the court, by way of an ex parte chamber summons application supported by an affidavit, within 14 days after the close of pleadings for leave of the court to issue a third party notice.

(iv) Interlocutory Applications

Interlocutory proceedings are proceedings that deal with the rights of the parties (plaintiff and defendant) in the interval between the commencement of the civil action and its final determination (i.e. before the court delivers the final judgment). One of the main functions is to ensure that the matter proceeds expeditiously and properly to trial. A party usually takes interlocutory proceedings to apply to the court for an extension of time for submitting certain documents, seek directions from the court regarding the conduct of the case, compel the other party to comply with the rules of the court or the court’s directions or apply to the court to grant such interim relief or remedy (e.g. an interim payment/compensation or injunction) as may be just or convenient.

Some common interlocutory applications are listed below.

- Application for extension of time for complying with certain directions under the rules of court or a court order. For example, the plaintiff may apply (with substantial reasons) to extend the deadline for filing a reply to a defence.

- Application for further and better particulars of the other party’s pleadings (Order 2 Rule 1).

- Application for striking out a particular pleading or part of the pleading of the other party. The applying party may rely on the grounds that the other party’s pleading (i) discloses no reasonable cause of action or defence, as the case may be; (ii) is scandalous, frivolous or vexatious; (iii) may prejudice, embarrass or delay the fair trial of the action; or (iv) is otherwise an abuse of the process of the court (Order 2 Rule 15).

- Application for amendment to the pleadings. The plaintiff and the defendant may each amend their own pleadings once before the close of pleadings, without the court’s prior permission. Further amendments require the permission of the court. For an amendment made by one party without the court’s permission, the other party shall have 14 days (after receiving the first party’s amended pleading) to amend his own pleading. For an amendment that requires the court’s permission, the court will specify the time for the other party to amend his own pleading (Order 8).

- Application for documents to be disclosed from the other party.

- Interlocutory applications can also be made by parties to a civil action to: (i) preserve a party’s rights before trial (i.e. injunctions – See Order 40) or (ii) to dispose of or to settle a civil action before the parties have to attend a full trial.

It must be noted that some interlocutory proceedings involve technical issues and arguments. It is not advisable to start such proceedings without legal advice. The court does not approve of the misuse of interlocutory procedure, which only wastes time and money.

3.2.5. Hearing and Consequences of Non-Attendance (Order 12)

It is central to note that when neither party attends, the court may dismiss the suit (rule 1). When only the plaintiff attends if notice of hearing was duly served, it may proceed ex parte. However, if that notice of hearing was not duly served, it shall direct a second notice to be served, or if notice was not served within sufficient time or for sufficient reason the defendant was unable to attend, it may postpone hearing (rule 2). If on the day of the hearing, only the defendant attends and he denies the claim, the suit shall be dismissed unless good cause is shown which should be recorded in court.

A. Pre-Trial Directions and Case Conferencing (Order 11)

Worth noting is that this Order applies to all suits except small claims as defined under Order 3(1) or such other suits as the court may by order exempt from this requirement (Rule 1). The aim of the pre-trial directions and case conferencing is to deal with preliminary issues well in advance so that the trial once commenced must proceed on a day to day basis without unnecessary interruptions. Time allocation is also dealt with at this stage. With a view to furthering expeditious disposal of cases and case management the court shall within 30 days after the close of pleadings convene a Case Conference in which it shall deal with the issues laid out in r.3 (1) (a-i) (r.3(1)).

B. Judgment and Decree

Once hearing is completed, the court will pronounce judgment. Rules 1-6 of Order 21 deals with judgment and Rules 7-19 of the same Order deals with decrees. A Judgment is a final decision of the court on the facts of the case at the end of the entire procedure. On the other hand, a Decree is a technical translation of the judgment capable of execution. In the High Court the parties themselves draw up the decree and take it back to court to be sealed. The decree should be in agreement with the judgment.

C. Execution of Decrees and Orders (Order 22)

The court may on the application of the decree holder, order the execution of an order by delivery of any property decreed against, by attachment and sale, or sale without attachment, by attachment of debts, by arrest and detention in prison of any person, by appointing a receiver or in such other manner as the nature of the relief may require. If the decree holder desires to execute, he must apply for execution either to the court that passed the decree or the court to which the decree is sent for execution.

3.2.6. Appeals

Every decree may be appealed from unless barred by some law. However, an appeal does not automatically lie against every order. Order 42 Rule 1 gives a list of orders from which an appeal lies from as of right. If you want to appeal on an order that is not on the list, you have to seek leave of court. Application for leave to appeal should be made in the first instance to the court which made the order that is being sought to be appealed against. It should be made by Chamber Summons within 14 days from the date the order is made or orally in court at the time of making the order. Appeals from the High Court are filed by lodging a memorandum of appeal which is usually set out in the same manner as pleadings. It is critical to note that the appeal does not automatically operate as a stay of execution. Even if an appeal has been lodged, and all parties served, the decree holder can proceed and apply for execution. The court appealed from may for sufficient cause order stay of execution of such decree or order.

3.2.7. Review

Review simply means to look at once again. Under the Civil Procedure Act, review is a judicial re-examination of the same case by the same judge in certain circumstances. Section 80 of the Act gives the substantive right of review in certain circumstances, while Order 45 provides the procedure thereof. Any person aggrieved by the decree order may apply for review. A person who is not a party to the decree or order cannot apply for review because such a decree will usually not be binding on such person and therefore cannot be said to have aggrieved them within the meaning of Order 45 and section 80. Usually persons aggrieved will apply for the review of the judgment where an appeal is allowed and where the appeal has not yet been filed. The grounds for review are thus; discovery of new and important matters of evidence that the court did not have when making a decision, where there is a mistake or error apparent on the face of the record or for any other sufficient reason.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

Following the adoption of the Constitution in Kenya in 2010, its implementation has seen significant improvements in the promotion and protection of human rights, gender equality and access to justice. The Constitution envisions a multifaceted, pluralistic judicial operative that recognizes the coexistence of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) and alternative justice systems within and alongside the formal justice system.[1] Article 159(2) thus envisages the underlying principles for the exercise of judicial authority in Kenya which include promotion of ADR and traditional dispute resolution (TDR) mechanisms.[2]

In this regard, Kenya’s new constitutional order recognizes the symbiotic and equal value of both the formal justice system and the wealth of traditional systems that have been operating in Kenya at the community level for hundreds of years. The judiciary is committed to realizing this and continues to support and undertake activities towards operationalizing alternative dispute resolution throughout the judicial system.

Access to justice by majority of citizenry has been hampered by many unfavourable factors which include inter alia, high filing fees, bureaucracy, complex procedures, illiteracy, distance from the courts and lack of legal knowhow.[3] This makes access to justice through litigation a preserve of select few. Through providing for the use of ADR and TDR mechanisms to enhance access to justice, the Constitution of Kenya was responding to the foregoing challenge in order to make the right of access to justice accessible by all.[4] It was in recognition of the fact that TDR and other ADR mechanisms are vital in promoting access to justice among many communities in Kenya. Indeed, a great percentage of disputes in Kenya are resolved at the community level through the use of community elders and other persons mandated to keep peace and order.[5]

Despite the formal recognition coupled with a constitutional mandate for their promotion in appropriate dispute resolution strategies, ADR mechanisms and other community justice systems are yet to be institutionalized by way putting in place supporting adequate legal and policy measures that would ensure effective utilisation of the same in access to justice. There exists no substantive policy or legislative framework to guide the promotion and use of these mechanisms despite their constitutional recognition and limitations set out under Article 159(2) and (3).[6]

The main alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods available in Kenya are negotiation, conciliation, mediation and arbitration. There is no mandatory requirement for parties to litigation or in dispute to submit to ADR proceedings. However, in terms of the Civil Procedure Act, the courts may, either on the application of the parties or on its own motion, refer a dispute to ADR mechanisms.

In ADR proceedings parties generally agree that each party will bear their own costs and expenses and the parties will share the costs of any third party involved in facilitating the resolution of the dispute (example, conciliator or mediator). In arbitration, the costs of arbitration may be agreed upon by the parties, fixed by the arbitrator as part of the arbitral award in the absence of an agreement; or shared, with each party bearing its own legal and other expenses and the parties equally sharing the fees and expenses of the arbitral tribunal and any other expenses relating to the arbitration. ADR proceedings are confidential.

The Kenyan Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and the Dispute Resolution Centre and Mediation Training Institute are currently the main bodies that offer ADR in Kenya. Parties are not obliged to use these bodies. They are free to state in their agreements how the ADR proceedings will be carried out and which body will oversee the proceedings. The parties are also free to choose individual qualified arbitrators.

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal process

In Kenya, most civil cases in the High Court and Magistrates’ Courts are decided under intricate procedural regimes contained in the Civil Procedure Act[7] and elaborate rules contained in over 180 pages of subsidiary legislation. Some matters such as matrimonial and company law issues have their own procedures as do most tribunals.

The original Civil Procedure Act was enacted in 1924 being a carbon copy of the Indian enactment, and since then, the Act and Rules have been amended many times mainly in a haphazard fashion. In December 2010 the Rules Committee comprising two judges of the Court of Appeal, two judges from the High Court, the Attorney General and two advocates promulgated a new set of rules.[8] It has been held that rules are designed to formulate the issues, which the court has to determine and to give fair notice to the parties, and that procedural rules are intended to serve as handmaidens of justice not to defeat it.

The Civil Procedure Act states that the overriding objective of the Act and rules is to facilitate the just, expeditious, proportionate and affordable resolution of the civil disputes and the court must give effect to these overriding objectives.[9] The adoption and adaptation of the overriding objective principle in Kenyan civil procedure and practice has had the effect of making the system better in achieving justice for all the parties to the suit. The principle of the overriding objective in interpretation of Kenyan Civil procedure has tremendously improved access to justice by the parties to the suit as compared to circumstances where the principle in the past was not invoked. However, there is great need for the Kenyan jurisprudence in the applicability of the principle to continue developing to be in tandem with contemporary developments in civil practice and procedure in other commonwealth countries and most notably, the United Kingdom.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

Access to justice forms a central theme in the Constitution of Kenya 2010. By definition, access to justice refers to “the provision of dispute resolution mechanisms which are affordable, proximate and ensure speedy justice and whose processes and procedures are understood by users”.[1] The Kenyan Constitution lays great emphasis on access to justice in at least four ways.

First, it has a substantive provision on access to justice: Article 48 states that the “State shall ensure access to justice for all persons and, if any fee is required, it shall be reasonable and shall not impede access to justice.”[2]

Second, Article 22 makes it easy for persons who have disputes about human rights to go to court either for themselves or on behalf of others, especially those who cannot act on their own behalf.[3] This type of access is broadened by Article 258 which provides that every person has the right to institute court proceedings, claiming that the Constitution has been contravened, or is threatened with contravention.

Third, Article 50, dealing with fair hearing contains provisions that create facilitative mechanisms to ensure that court processes are fair, especially to the poor. It provides that those with disputes have a right to a lawyer (which means a lawyer they hire themselves), but importantly requires that an accused person have an advocate assigned “by the State and at State expense, if substantial injustice would otherwise result, and to be informed of this right promptly.”[4]

Finally, Article 159 provides for some minimum principles that should guide access to justice, including that justice shall be done to all irrespective of their status, it should not be delayed and that procedural technicalities should not be used as a bar to achieving substantive justice. In many ways the access to justice provisions have been revolutionary in changing the manner in which justice has been administered since the promulgation of the 2010 constitution, perhaps the greatest positive impact coming from Article 159 principles and Article 22 provisions.

The Judiciary is expected to bring the new Constitution to life by changing it from a policy into a living, breathing document which promotes its values and principles and advances the rule, human rights, access to justice, and develops the law and contributes to good governance. In this regard, the Kenyan judiciary has experienced a number of administrative reforms, including the introduction of the Judicial Transformation Framework (2012-2016),[5] which aimed to turn Kenya’s judiciary and courts into an independent, efficient and transparent legal system.

The Judiciary Transformation Framework identified four pillars of reform: “people-centered” delivery of justice; improving organizational culture and professionalism; ensuring adequate infrastructure and resources; and making better use of information technology. The first pillar, focused on ensuring access to justice and public engagement, included such actions as establishing customer care desks to answer questions, simplifying court procedures, creating a case management system, and strengthening complaint mechanisms. The second pillar focused on changing the judiciary’s institutional culture, increasing training, and clarifying individuals’ responsibilities. The third and fourth pillars sought to expand the court system, to computerize its procedures, and to upgrade its IT infrastructure.

The Framework was successful in meeting its objectives, guided by its underlying philosophy of laying the foundations of Judiciary transformation. Thus, during those five years, its record of institutional building and capacity enhancement was impressive: new High Court and Magistrates Court stations were established in Counties; the Court of Appeal was decentralised; more judges, magistrates, and kadhis were recruited; court infrastructure was built or improved countrywide, management systems and processes were put in place; nearly 40 policies, plans, manuals and regulations were developed and published; key employees were hired and their terms and capacities significantly improved; training was revived; the budget was increased and revenue collection dramatically shot up; a data culture was introduced and several service delivery pilot projects were undertaken.[6]

In order to sustain the gains made under the 2012-2017 Framework, the judiciary adopted a bottoms-up approach which was codified under a new framework: Sustaining Judiciary Transformation (SJT): A Service Delivery Agenda (2017-2021),[7] and which is focused on service delivery. In launching this new framework and as an expression of political will in promoting the values of access to justice, the Kenyan Chief Justice – Justice David Kenani Maraga – expressed himself in the following words:[8]

“…In the institutional framework document, I have outlined six strategic Big Bets, which espouse my vision for the Judiciary. Please allow me to briefly outline the essence of each of these action points. Enhancing access to Justice: Many ordinary Kenyans hold the view that the formal justice system is not for them. Several factors account for this: Either the courts are too far away from where they live, or; they do not understand court processes, or; unfortunately, and quite often, they cannot afford the fees required to prosecute or defend their cases to conclusion. I recognise that in the last five years, the Judiciary, has invested in more magistrates courts, especially in sub-counties that did not have them; established more High Court Stations; decentralized the Court of Appeal; and piloted Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) programmes such as Arbitration and Court-Annexed Mediation processes. But a lot more remains to be done. The Court-Annexed Mediation has proved successful in both the Commercial and the Family Divisions of the High Court in Nairobi. We propose to roll these ADR processes to all other courts in the country. Our pilot projects on traditional methods of dispute resolution, in several communities, such as the Kipsigis, the Kikuyu, the Kamba, the Turkana, the Meru, the Tugen and the Somali have proved fairly successful. In the next phase of this project we intend to bring into the fold all other communities across the country. I am convinced that in collaboration with the Judiciary, these communities and many others in the country will settle many disputes and thus obviate the need to file their claims in court. Plans are also under-way to operationalize the Small Claims Court, and fully institutionalise all statutory Tribunals and to assist indigent litigant, we are taking necessary action to operationalize the Legal Aid Act as soon as possible…”

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

Prior to the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya, the government provided legal aid services to indigent persons, albeit in limited manner. Legal aid was only available to accused persons who were charged with capital offences of murder facing trial in the High Court. Other criminal offences did not attract legal assistance from the state, exposing the accused persons to the rigours of the adversarial justice system. The civil procedure code had a window allowing those who could not afford fees to sue as a pauper, but the procedure of going through this process to determine eligibility was daunting. The criminal paupers’ briefs were managed by the judiciary who then in turn appointed advocates to take up the matters at a paltry fee which discouraged senior lawyers from taking up such cases.

With the increased demand for access to justice, the government took greater initiative to establish an institution that would spearhead provision of legal aid services. In 1999, the Legal Aid Steering Committee under the aegis of the AG’s Office, commissioned a consultancy to design a pilot programme for testing suitable model(s) for a National Legal Aid Scheme. In a 2001 report the National Legal Education and Aid: Pilot Programme, the consultants proposed a framework for piloting legal aid and awareness programme in Kenya. However, the report was not validated until 2005 when the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs hand-picked other consultants to review the earlier report. After the review the report was subsequently validated in 2006 and led to the establishment of NALEAP in 2007 vide Gazette Notice of 2007.

This was a build-up from previous efforts at creating a legal aid programme by the Attorney-General’s office and other stakeholders.[1] The main objective of the pilot programme was to test an affordable, practical legal aid and service delivery scheme for indigent persons in line with government constitutional and international obligations on access to justice. The pilot programme was further designed to provide lessons for the design and development of an appropriate national legal aid legislation and policy. This Action Plan seeks to operationalize the Legal Aid Act and the Policy.

The initiatives by the state point towards positive efforts to expand access to justice for indigent through legal aid. In addition to government efforts, Civil Society Organisations (CSO) such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and Community-Based Organisations (CBOs) including Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs) have initiated projects and programmes geared towards providing legal aid and legal awareness based on their specific areas of focus such as children’s rights, rights of persons with disability, women’s rights, prisoners, land rights, among others. The problem has been the steady increase for demand for legal aid services that outstrips the supply by the existing legal providers. In most cases the legal aid services offered by the various institutions are mandate driven.[2] Therefore many needy persons who do not fit into the selected eligibility criteria or specialized themes do not get to benefit from those services.

The policy approach is aimed at ensuring a more sustainable and systematic government approach to legal aid provision. One of the most significant contributions of these schemes has been the breaking away from the old-fashioned philanthropic focus of the official interventions by addressing some class aspects of the problem, by promoting social change and empowerment. Additionally, there is a paradigm shift in legal aid provision as the service is now anchored in the law creating better structure and modalities of operations. In spite of the initiatives by state and non-state actors to promote legal aid having had some degree of success, the demand for legal aid services is overwhelming and has stretched the capacities of relevant bodies and stakeholders involved in legal aid to their limits. Legal aid providers have been largely uncoordinated and their reach is limited as they are mainly located within major urban and peri-urban centers, leaving out rural and the marginalized populations in parts of Kenya. There have also been challenges with supervision, enforcement, standardization, and regulation, the frequency and quality provision of legal aid services by these stakeholders.

In spite of the initiatives by state and non-state actors to promote legal aid having had some degree of success, the demand for legal aid services is overwhelming and has stretched the capacities of relevant bodies and stakeholders involved in legal aid to their limits. Legal aid providers have been largely uncoordinated and their reach is limited as they are mainly located within major urban and peri-urban centers, leaving out rural and the marginalized populations in parts of Kenya. There have also been challenges with supervision, enforcement, standardization, and regulation, the frequency and quality provision of legal aid services by these stakeholders.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

On 27 august 2010, the promulgation of Kenya’s 2010 Constitution marked a new chapter on the right to a justice related rights in the country. The 2010 Constitution sought to re-orient and advance to a new level justice related rights. It recognizes the right to legal aid as an integral component to a fair trial. The Constitution guarantees the right of every person to access justice and more particular legal aid to accused persons and calls upon the State to take appropriate policy, statutory and administrative interventions to ensure the efficacy of justice systems.[3]

Kenya also has enacted the Legal Aid Act, 2016.[4] The objective of the Act is to facilitate access to justice and social justice, establish the National Legal Aid Service, provide for legal aid, and funding of legal aid in Kenya. A closer look at the salient features of the Act reveals an ambitious and comprehensive legal regime. The preamble, guiding principles and objects of the Act are anchored on constitutional provisions and spirit contained under Articles 19 on rights to fundamental freedoms, Article 48 on right to access justice, Article 50(2)(g)(h) on the right to choose counsel and be informed of legal representation at the expense of the state.

The country formally launched and adopted a National Action Plan on Legal Aid for 2017-2022, the first of its kind in Kenya and in the African region.[5] The Action Plan outlines a broad policy, legal and institutional framework to ensure sustainable and quality legal aid, and operationalizes recent legislation including the National Legal Aid and Awareness Policy 2015 and the Legal Aid Act 2016. The National Action Plan provides a road map that was previously missing in terms of ensuring effective provision of legal aid services by the government and other stakeholders. It is hinged on collaborative and cooperative effort in legal aid service provision. It brings on board all the legal aid providers into one umbrella for easy coordination and quality assurance. Awareness-creation is at the core of the Plan and makes it the business of providers to facilitate legal rights education at community level. Another important component of the Plan is the matrix which stipulates activities to be undertaken, responsible actors and timeframe for easier accountability. Importantly, the Action Plan puts responsibility squarely on government to provide legal aid.

The strategic objectives of Kenya’s National Action Plan on Legal Aid include:

(a) To strengthen framework for policies, laws and administrative processes that will ensure sustainable and quality access to justice to all;

(b) To provide quality, effective and timely legal assistance, advice and representation for the poor, marginalized and vulnerable;

(c) To enhance access to justice through legal aid and awareness;

(d) To promote and institutionalize the paralegal approach in access to justice;

(e) To promote the use of alternative and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms;

(f) To establish an implementation, monitoring, regulatory and support framework;

(g) To allot fiscal, human and technical resources for legal aid and awareness services in Kenya;

(h) To undertake research to ensure evidence-based initiatives.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

As has been highlighted above, the Legal Aid Act 2016 regulates the provision of legal aid services in Kenya and has gone further to establish the National Legal Aid Service (“NLAS”) to provide legal aid services at the expense of the State to persons who qualify for legal aid services under the Act.[6] The NLAS, hosted under under the Attorney General’s office, is established to offer affordable, accessible, sustainable, credible and accountable legal aid service to the vulnerable.

The functions of the Service include the following:[7]

(a) Establish and administer a national legal aid scheme that is affordable, accessible, sustainable, credible and accountable;

(b) Advise the Cabinet Secretary on matters relating to legal aid in Kenya;

(c) Encourage and facilitate the settlement of disputes through alternative dispute resolution;

(d) Undertake and promote research in the field of legal aid, and access to justice with special reference to the need for legal aid services among indigent persons and marginalized groups;

(e) Take necessary steps to promote public interest litigation with regard to consumer protection, environmental protection and any other matter of special concern to the marginalized groups;

(f) Provide grants in aid for specific schemes to various voluntary social service institutions, for the implementation of legal aid services under this Act;

(g) Develop and issue guidelines and standards for the establishment of legal aid schemes by Non-Governmental Agencies;

(h) In consultation with the Council of Legal Education, develop programs for legal aid education and the training and certification of paralegals;

(i) Promote, and supervise the establishment and working of legal aid services in universities, colleges and other institutions;

(j) Promote the use of alternative dispute resolution methods;

(k) Take appropriate measures to promote legal literacy and legal awareness among the public and in particular, educate vulnerable sections of the society on their rights and duties under the Constitution and other laws;

(l) Facilitate the representation of persons granted legal aid under this Act;

(m) Assign legal aid providers to persons granted legal aid under this Act;

(n) Establish, coordinate, monitor and evaluate justice advisory centers;

(o) Coordinate, monitor and evaluate paralegals and other legal service providers and give general directions for the proper implementation of legal aid programs;

(p) Administer and manage the Legal Aid Fund; and

(Q) Perform such other functions as may be assigned to it under this Act or any other written law.

5.4. Legal aid budget

The National Action Plan on Legal Aid mandates the government, through the National Legal Aid Service, to establish funds from the Exchequer and development partners to finance legal aid activities and programs across the country. A majority of civil society organizations providing legal aid in Kenya obtain funding from donors and well-wishers.

5.5. Legal aid providers

The Legal Aid Act broadly examines the issue of accreditation of legal aid providers as set out under section 56.[8] Pursuant to Part VII of the Act, in order for one to be an accredited paralegal, he/she needs to make a written application to the Board. The Service is required keep a register of all accredited paralegals which shall include the personal details and contact addresses of all accredited legal aid providers, in the case of a registered association or a public benefit organization, the nature of the association or organization and the particulars of its registration, the nature of services in respect of which the legal aid providers are accredited, the number of cases being handled by the legal aid provider at any given time and any other matter prescribed by regulations.

5.6. Quality assurance

Much has been done by the government and other stakeholders to provide legal aid in Kenya. However, until recently when National Legal Aid Action Plan 2017-2022 (NLAAP) was adopted and the Legal Aid Act enacted, these efforts did not derive from a known comprehensive policy, and they were not legally documented. Legal aid legislation and the implementation, monitoring, regulatory and support processes involved were scattered over various national and international legislations which Kenya is party to. The absence of a policy and regulatory framework for legal aid service provision also means that there was no set standard for service delivery and no clear mechanism to manage or control the services provided. Additionally, although there has been a general expansion of legal aid provision in the country, without a clear strategic plan of action, the related policy and legal framework aspects remain weak. The result is low levels of regulation and coordination of legal aid services with regard to planning, implementation, funding as well as monitoring and evaluation.

Implementing, monitoring and evaluating regulatory and support framework for legal aid is critical for measuring performance and evaluating the impact of interventions. These systems include periodic surveys, audits and assessments. Feedback on monitoring and evaluation is necessary to ensure that the information obtained is used to improve, strengthen or change strategy in provision of services. Because of the inherent susceptibility to criticism of the quality of any service provided by the state at no cost to the citizen, it is important for a provider of legal aid services to have stringent quality control measures in place. It is therefore important to develop a comprehensive quality monitoring and intervention programme.

Under Strategic Objective 6 of the NLAAP, the following priorities have been set:

- Establish training and accreditation systems for legal aid providers;

- Set up systems for quality assurance to ensure quality of services;

- Develop clear accreditation for legal aid service providers;

- Develop system and mechanisms for data collection, analysis and dissemination to inform programming;

- Develop procedures and policies that are universally acceptable for monitoring and evaluation;

- Establish or strengthen existing tools or mechanism for monitoring and evaluation.

5.7. Criminal legal aid

5.7.1. Scope of criminal legal aid

In Kenya, the idea of legal aid has now been guaranteed by the constitution through two provisions. Article 48 recognizes the right of access to justice for all, which implies a lawyer when necessary. And Article 50(2)(h) is explicit, stating that every accused person has a right to fair trial including the right “to have an advocate assigned to the accused person by the State and at State expense, if substantial injustice would otherwise result.”[9]

While Article 50(2)(h) is specific on legal aid, there are many other provisions of the constitution that are relevant to the concept of legal aid. These includes the value of social justice under Article 10,[10] provision on equality before the law under Article 27, provisions on protection of marginalised and vulnerable persons, and the requirement under Article 159 that justice shall be done to all irrespective of status. The overarching context to be derived from these provisions is that it is impossible to achieve justice where one party (the poor) has to contend either with the elaborate machinery and resources available to the opposite party (usually the State). Where then an average and poor person is faced with a legal process (and especially in complex and high stakes criminal trials) it is unfair and unjust if they cannot be represented by an advocate who can ensure that they enjoy the full protection of the law.

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

Section 36(1) of the Legal Aid Act provides for eligibility for legal aid. In this regard, a person is eligible to receive legal aid services if that person is indigent, resident in Kenya and is:

(a) a citizen of Kenya;

(b) a child;

(c) a refugee under the Refugees Act;

(d) a victim of human trafficking; or

(e) an internally displaced person; or

(f) a stateless person.

This requirement, according to my opinion contravenes the Constitution which recognises the right of “every accused person” to a lawyer. A person who is eligible to receive legal aid services under subsection (1) shall apply to the Service in the prescribed manner.[11] A person shall not receive legal aid services unless the Service has determined that the individual’s financial resources are such that the person is eligible for the services. The Legal Aid Service shall not provide legal aid services to a person unless the Service is satisfied that:[12]

- the cost of the proceedings is justifiable in the light of the expected benefits;

- resources are available to meet the cost of the legal aid services sought;

- it is appropriate to offer the services having regard to the present and future demands;

- the nature, seriousness and importance of the proceedings to the individual justify such expense;

- the claim in respect of which legal aid is sought has a probability of success;

- the conduct of the person warrants such assistance;

- the proceedings relate to a matter that is of public interest;

- the proceedings are likely to occasion the loss of any right or the person may suffer damages;

- the proceedings may involve expert cross-examination of witnesses or other complexity;

- it is in the interest of a third party that the person be represented;

- denial of legal aid would result in substantial injustice to the applicant; or

- there exists any other reasonable ground to justify the grant of legal aid.

5.7.3. Process for obtaining criminal legal aid

Section 40 of the Legal Aid Act provided for the procedure for applying for legal aid. In this regards, a person who wishes to receive legal aid, shall apply to the Service in writing.[13] Where a person wishes to apply for legal aid the person shall apply before the final determination of the matter by a court, tribunal or any other forum to which the application relates.[14] The Legal Aid Service evaluates the application for legal aid and makes a determination using the eligibility criteria provided in the foregoing section. Section 41 of the Act provides that the application may either be made by:

- the applicant in person;

- any other person authorized by the applicant in writing;

- any person or organization authorized by the applicant in writing, on behalf of the applicant; or on behalf of the applicant where the authority of the applicant cannot be reasonably obtained due to physical or mental incapacity.

The Legal Aid Act further obligates the officer-in-charge of a prison, police station, remand home for children or other place of lawful custody to:[15]

- ensure that every person held in custody, is informed, in language that the person understands, of the availability of legal aid on being admitted to custody and is asked whether he or she desires to seek legal aid;

- maintain a register in which shall be entered the name of every person held there and the response of each such person when asked if he or she desires to seek legal aid; and

- ensure that a legal aid application form is made by a person in their custody wishing to apply for legal aid and shall inform the Service of the application within twenty-four hours of the making of the application.

Failure to fulfill the above obligations in a bid to willfully obstruct a person held in lawful custody from applying for legal aid results in an offence. According to Section 43(1) of the Act, a court before which an unrepresented accused person is presented shall promptly inform the accused of his or her right to legal representation and if substantial injustice is likely to result, promptly inform the accused of the right to have an advocate assigned to him or her. The court shall further inform the Legal Aid Service to provide legal aid to the accused person.

5.8. Civil legal aid

5.8.1. Scope of civil legal aid

The Constitution of Kenya 2010 under Article 50(1) provides that every person has the right to have any dispute that can be resolved by the application of law decided in a fair and public hearing before a court or, if appropriate, another independent and impartial tribunal or body. The reach of this constitutional provision goes beyond criminal matters. A fair hearing (required in Article 50(1)) should also apply to other matters when one or both parties cannot afford an advocate, such as legal custody of children, or claims for social security, or accident compensation, to take just a few.

Under the Legal Aid Act, provision for legal aid covers both criminal and civil cases. The civil cases covered include constitutional cases, and also the provision of legal advice about civil cases. Administrative tribunal cases are also covered (maybe not the sort of cases that the poor generally get involved in, though a de-registered teacher appealing to the Teachers Service Appeal Tribunal might be eligible). Some sorts of legal cases are not covered at all, including tax, debt cases, bankruptcy and defamation (even if you are sued and not the person trying to get compensation).[16]

5.8.2. Eligibility criteria for civil legal aid

In order to be eligible for legal aid, a person must be unable to pay for legal services.[17] Being indigent is not enough to warrant access to legal aid. A person must be resident in Kenya, and be either a child, citizen, refugee, or trafficked or stateless person. A non-citizen adult accused of a crime, and who is not a refugee or stateless is not eligible to apply for legal aid.

Legal aid cannot be given to a company, trust or association. This requirement is unfair to small companies and community based organizations that may not be able to afford legal fees.

5.8.3. Process for obtaining civil legal aid

A person who wishes to receive civil legal aid, shall apply to the Legal Aid Service in writing.[18]

5.9. Holistic legal services

The National Legal Aid Action Plan under Strategic Objective 2 aims at providing quality, effective and timely legal assistance, advice and representation for the poor, marginalized and vulnerable. The Priority area / strategic action three under this objective is to form strategic partnerships with private sector, CSOs, CBOs, NGOs and other non-governmental entities to undertake legal aid. As such, when implemented, this priority area seemingly will result in possible link-ups between legal services providers and non-lawyer professionals to provide a “one stop shop” for legal aid in Kenya.

5.10. Alternative sources of legal assistance

Equal access to justice remains a challenge for most people in Kenya. Aside from the limited provision of state-funded legal aid, a large number of Kenyans have few options to access the judicial system with proper representation. The majority of pro bono legal services are provided by non-governmental organizations (“NGOs”), which are located mainly in large cities, and which lack the resources and capacity to represent the large number of Kenyans in need of legal advice. Without representation, most Kenyans are unable to manoeuvre the legal system because of the complex legal procedures, lack of education regarding legal rights and the court system, financial impediments or other time and resource constraints. Kenya faces significant challenges in implementing a legal system that serves its population adequately, but it is making strides in the right direction.[19]

Some of the non-governmental organizations offering legal aid in Kenya include the following:

A. Federation of Women Lawyers (“FIDA Kenya”)[20]

FIDA Kenya is a non-profit, non-partisan membership-based NGO committed to the creation of a society that is free from all forms of discrimination against women. They address their mission by providing pro bono advice to indigent women, engaging in legal, policy and legislative reform, monitoring the implementation of treaties, researching issues related to women’s rights, and educating women about their rights. FIDA Kenya has assisted women through various programs and initiatives, including training women to represent themselves in court. The primary areas of law that they cover are succession and inheritance, family law, employment cases and land disputes involving discrimination on the basis of sex, cases involving gender-based violence and other public interest cases. FIDA Kenya has established a country-wide pro bono lawyer’s scheme and engages in legal awareness activities and alternative dispute resolution.[21]

B. Public Law Institute (“PLI”)[22]

PLI is an NGO that was created by the National Council of Churches of Kenya and the Law Society of Kenya to promote human rights and the rule of law in Kenya. PLI’s activities include providing legal representation and services to the poor and disadvantaged, and protecting consumer and environmental rights. PLI also provides legal education through publications, workshops, seminars and paralegal training programs.

C. KELIN Kenya (“KELIN”)[23]

KELIN was registered as an NGO in 2001. It is a human rights organization working to protect and promote HIV-related human rights in Kenya. The NGO’s objective is to undertake advocacy and provide leadership in enhancing human rights approaches in health, as well as HIV strategies and programs. KELIN does this by providing legal services and support, training professionals on human rights, engaging in advocacy campaigns that promote awareness of human rights issues, conducting research, and influencing policy that promotes evidence-based change. KELIN works with vulnerable and often marginalized groups such as people living with HIV and at-risk populations. It also engages with key stakeholders, policy makers and involves itself in the process of policy development and reform in order to improve protection against health and HIV-related human rights violations for such groups.

D. Kituo Cha Sheria[24]

Kituo Cha Sheria is a national membership-based NGO founded by lawyers committed to helping disadvantaged and poor people who cannot afford the cost of legal services. Established in 1973, it was the first legal aid center in Kenya and focuses on empowering marginalized and poor people to access justice though legal aid education, advocating for equitable access to justice, establishing community partnerships, and undertaking public interest litigation. The organization provides legal advice regarding family law, land disputes, employment and labor disputes, landlord and tenant issues, criminal offences, accident claims, rape cases, women’s rights issues, and refugee issues. Kituo Cha Sheria is largely dependent on donors and lawyers who volunteer their services, which can make its ability to provide consistent levels of service unpredictable. The organization is headquartered in Nairobi, has a branch office in Jogoo Road and a regional office in Mombasa, in addition to an established network of volunteer lawyers in major towns throughout the country.

E. International Commission of Jurists in Kenya (“ICJ-Kenya”)[25]

ICJ-Kenya is a non-profit, non-partisan membership-based NGO with over 300 members who are dedicated to the legal protection of human rights in Kenya. The organization has a permanent secretariat with a team of full-time lawyers charged with running its programs. ICJ-Kenya’s objectives include improving access to justice and protection of human rights, increasing citizen empowerment, investing in the development and involvement of key stakeholders, and increasing awareness of human rights.

F. The CRADLE – Children’s Foundation[26]

The CRADLE is a non-profit NGO committed to the protection, promotion and enhancement of the rights of children, especially girls. The organization was started by a group of Christian lawyers to respond to the need for the provision of legal assistance to children and it works to enhance children’s access to justice. The CRADLE’s activities include running a legal aid program, advocating for policy and legislative enactments protecting children’s rights, researching, monitoring and documenting issues related to children’s rights, and building awareness of children’s rights.

G. Transparency International[27]

Founded in 1999 in Kenya, TI-Kenya is a not-for-profit organisation with the aim of developing a transparent and corruption-free society through good governance and social justice initiatives. Transparency International Kenya offers FREE legal advice on corruption related cases under the Advocacy and Legal Advice Centre (ALAC). ALAC is a walk-in, call-in and mail centre where any person can obtain free and confidential advice on corruption cases. TI-Kenya in collaboration with government commissions and coalition partners against corruption in Coast, North Rift, Western and Nairobi regions are working to empower citizens to actively participate in the fight against corruption in Kenya.

H. Law Society of Kenya (LSK)[28]

The Law Society of Kenya is a statutory membership body established pursuant to the Law Society of Kenya Act, 2014[29] and drawing membership from all advocates – currently totaling over 14,000. The LSK has over the years provided leadership and technical support to the country in order to deliver justice, advance the rule of law, protect constitutionalism and improve access to justice at both national and county levels.[30] The LSK Strategic Plan 2017-2021 outlines several flagship initiatives aimed at aiding the realization of the objects of the organization, including provision of legal aid and the establishment of a legal aid call centre.[31] The Law Society of Kenya, in conjunction with the judiciary of Kenya, offers annual legal aid and pro bono services over a number of days at its branches throughout Kenya. In Nairobi, lawyers advise pro bono clients at the grounds in the High Court of Kenya and Milimani Law Courts.

I. Legal / Law Clinics and Law Students

Some Kenyan universities have established legal aid clinics that allow students to provide pro bono assistance during their legal studies. This is a relatively recent development, arising from the growing acceptance of incorporating practical skills into legal education. This recognition can be traced back to 1994, following the establishment of the Moi University Faculty of Law. Through the Moi University Legal Aid Clinic, students can render legal advice and routine legal assistance to indigent clients.[32] By using legal education as a tool for engaging and assisting the public, students can also learn to be competent lawyers committed to the provision of quality legal services and the ideal of social justice. Another example of a legal clinic in Kenya is the Strathmore University Law Clinic which is a nascent law clinic that commenced its activities in 2015.[33] It aims to contribute to the achievement of the Strathmore Law School’s vision of being a center renowned for excellence in legal education and research, guided by a commitment to pursue justice.

5.11. Peculiarities of legal aid in Kenya

The enactment in 2016 of the Legal Aid Act marked a significant milestone in the development of the justice system in Kenya. It signified the equality of all citizens through the provision of free legal services to the vulnerable and indigent of the society ensuring justice for all. The launch of the National Action Plan on Legal Aid (2017-2021), the first one in Kenya, marked a great milestone in the journey towards creating an enabling environment for legal aid in Kenya.

Since independence in 1963, legal aid has been offered by both state and non-state actors, with non-state as the major provider, operating without any clear legal, institutional and coordination framework. However, with the enactment of the Legal Aid Act 2016 and a National Legal Aid and Awareness Policy, 2015, the Government of Kenya has adopted a collaborative and systemic approach that brings together both state and non-state actors in a coordinated manner in the delivery of legal aid.

The National Action Plan sets out major initiatives that address legal aid concerns across the country. The Plan provides the necessary impetus to operationalise the Legal Aid Act 2016 and a National Legal Aid and Awareness Policy, 2015 and ensures that efforts towards its implementation remains continued and focused. In Kenya, one of the greatest challenge that the justice sector has faced in the past, that has been an impediment to the allocation of adequate resources, is the lack of appreciation of the linkage between legal aid and development. The National Action Plan for Legal Aid addresses this challenge by positioning legal aid issues in the overall development agenda of the country by highlighting the cross-sectoral linkages. The National Action Plan provides the broad strategic framework on legal aid and ensure that there is synergy and coordination amongst the stakeholders – and in turn ensuring that legal aid is responsive, affordable, accessible and speedy.

The Plan demonstrates a strong commitment by Government to ensure that the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights of the Constitution of Kenya particularly on access to justice, are not only safeguarded but are realised in a systematic manner. It fosters transparency and accountability in the dispensation of Government’s obligations and commitments under national, regional and international legal framework on access to justice.

6. COSTS OF RESOLVING DISPUTES WITHIN THE FORMAL JUDICIAL MACHINERY

6.1. Overview of judicial costs for litigants

Generally, the party who is successful in a High/Subordinate Court proceeding may ask the court for an order that the unsuccessful party pay their costs. These costs are commonly referred to as “party/party” costs. The “costs” are to partially indemnify a person for the legal costs incurred by them or the time spent prosecuting or defending a court proceeding. The costs are then, based on the tariff set out in the Advocates (Remuneration) (Amendment) Order, (specific Year).

All court related civil matters are said to be litigation matters and the law sets the minimum fees. The mechanism of charging fees is different in the High Court with subordinate courts having a separate scale of fees. In civil litigation, there are two distinct methods of determining fees and these are said to be ‘party and party’ fees and ‘advocate and client’ fees.

6.1.1. Before the hearing