National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

Italy is a parliamentary republic; although over the years its Constitution has been the subject of some reforms, which have changed its original centralized system, introducing a form of regional decentralization, the jurisdiction is still exclusively attributed to the competence of the State (Article 117 of the Italian Constitution).

According to the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istituto italiano di statistica data http://dati.istat.it) at 1st January 2019 the resident population was 60,359,546 inhabitants, of which 5,255,503 foreigners; among the latter the most substantial ethnic groups are represented by Romanians (1,207,000), Albanians (441,000), Moroccans (423,000), Chinese (300,000) and Ukrainians (239,000), who alone constitute 50% of the foreign resident population in Italy (National demographic balance 2018, p. 6; https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/07/Statistica-report-Bilancio-demografico-2018.pdf). The predominant religion is the Christian one, in its three components, Roman Catholic (by far the majority), Protestant and Orthodox, but there are numerous minorities, especially Muslims and Jews (Center for Studies on New Religions – Centro studi sulle nuove religioni https://cesnur.com/il-pluralismo-religioso-italiano-nel-contesto-postmoderno-2/).

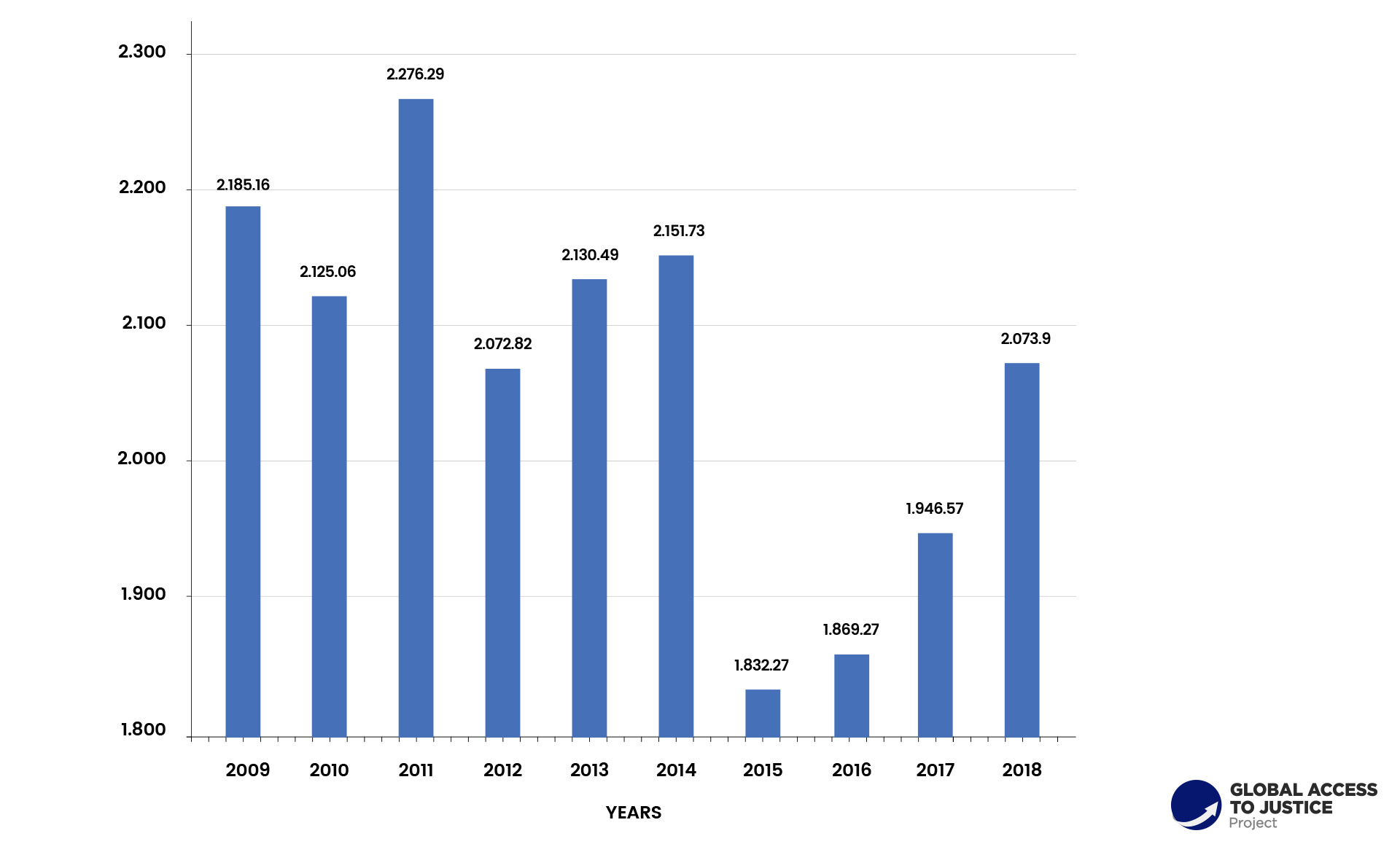

The GDP of 2018 is around two thousand billion dollars, while the ten-years trend is illustrated by the graph below, also calculated in billions of US dollars (data https://it.tradingeconomics.com/italy/gdp).

The GDP of 2018 is around two thousand billion dollars, while the ten-years trend is illustrated by the graph below, also calculated in billions of US dollars (data https://it.tradingeconomics.com/italy/gdp).

Chart 01. Italy GDP for the last ten years (2009-2018)

The 2018 Gross National Income at purchasing power parity per capita (PPP) is 42,49 $ (World Bank data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD?year_high_desc=true).

The 2017 Inequality Index value is 0.771 (data http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018_human_development_statistical_update.pdf), while the 2016 poverty rate was 0.137 (data https://data.oecd.org/inequality/poverty-rate.htm).

The life expectancy at birth are 83,2 years, the expected years of schooling are 16,3, while the mean years of schooling are 10,2 (http://hdr.undp.org/en/2018-update).

The 2018 Human Developement Index (HDI) is 0,880 (http://hdr.undp.org/en/2018-update).

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

The Italian Republic was established as a result of a popular referendum that on June 2, 1946 sanctioned the end of monarchy. On the same date, the members of the Constituent Assembly were elected; the Constitution of the Italian Republic went into force on January 1, 1948.[1] The Constitution reflects the principle of separation of powers, even though the separation cannot be seen as a harsh divide, since there is a constant interplay among the legislative, the executive and the judicial power. The Italian Constitution is what is conventionally called a ‘rigid’ constitution, since it cannot be changed or repealed like any other ordinary statutes: its amendments require a specific supermajority in both houses of the Parliament.

The Constitutional Court is in charge of deciding cases in which the consistency with the Constitution of the statutes applicable to cases pending before the judiciary is challenged: according to a renowned Italian scholar, ‘More than 50 years of constitutional review in Italy have brought about a consolidation of the position of the Constitutional Court’,[2] even though the occasions when the Court has become the target of harsh criticism coming at times by politicians, other times by the public opinion have multiplied in recent years.

The head of state is the President of the Republic, elected for a seven years term by the two houses of the Parliament at a joint session: he has variety of powers and prerogatives that make his role very important, since he ‘represents national unity’ (Article 87, sec. 1 of the Constitution)[3] and is the ultimate guarantor of the Constitution.

The legislative power is vested with the Parliament that is comprised of two chambers, the Chamber of Deputies (Camera dei Deputati, in Italian) and the Senate (Senato, in Italian): Article 70 of the Constitution provides that ‘The law-making function shall be exercised collectively by both Houses.’ The two chambers have virtually the same powers, so that one may say that Italy had adopted a system of perfect bicameralism, a system that has been repeatedly criticized as a source of inefficiency in the process by which bills become law in force.

The executive power is entrusted with the Government, which includes the Council of Ministers and the President of the Council. According to Article 95 of the Constitution, ‘The President of the Council shall conduct and be accountable for the general policy of the Government. The President of the Council shall ensure the consistency of political and administrative policies, by promoting and coordinating the activities of Ministers.’

As far as the judiciary is concerned, the Constitutions provides that ‘Judicial proceedings shall be exercised by ordinary magistrates empowered and regulated by the provisions concerning the Judiciary’ (Article 102, sec. 1). A few other constitutional rules are worth mentioning in order to give a better view of Italian judiciary. Therefore, the judiciary ‘shall be autonomous and independent of all other powers’ (Article 104, sec. 1); the recruiting, posting and transferring, as well as any decision concerning promotions and the infliction of disciplinary measures fall within the jurisdiction of the High Council for the Judiciary that is the self-governing body of the judiciary, in operation since 1958 (Articles 104 – 107). Ordinary judges are recruited through competitive examinations (Article 105); once in office they are considered public servants, even though their status is surrounded by special guarantees aimed at securing that they stay neutral, independent, and impartial.

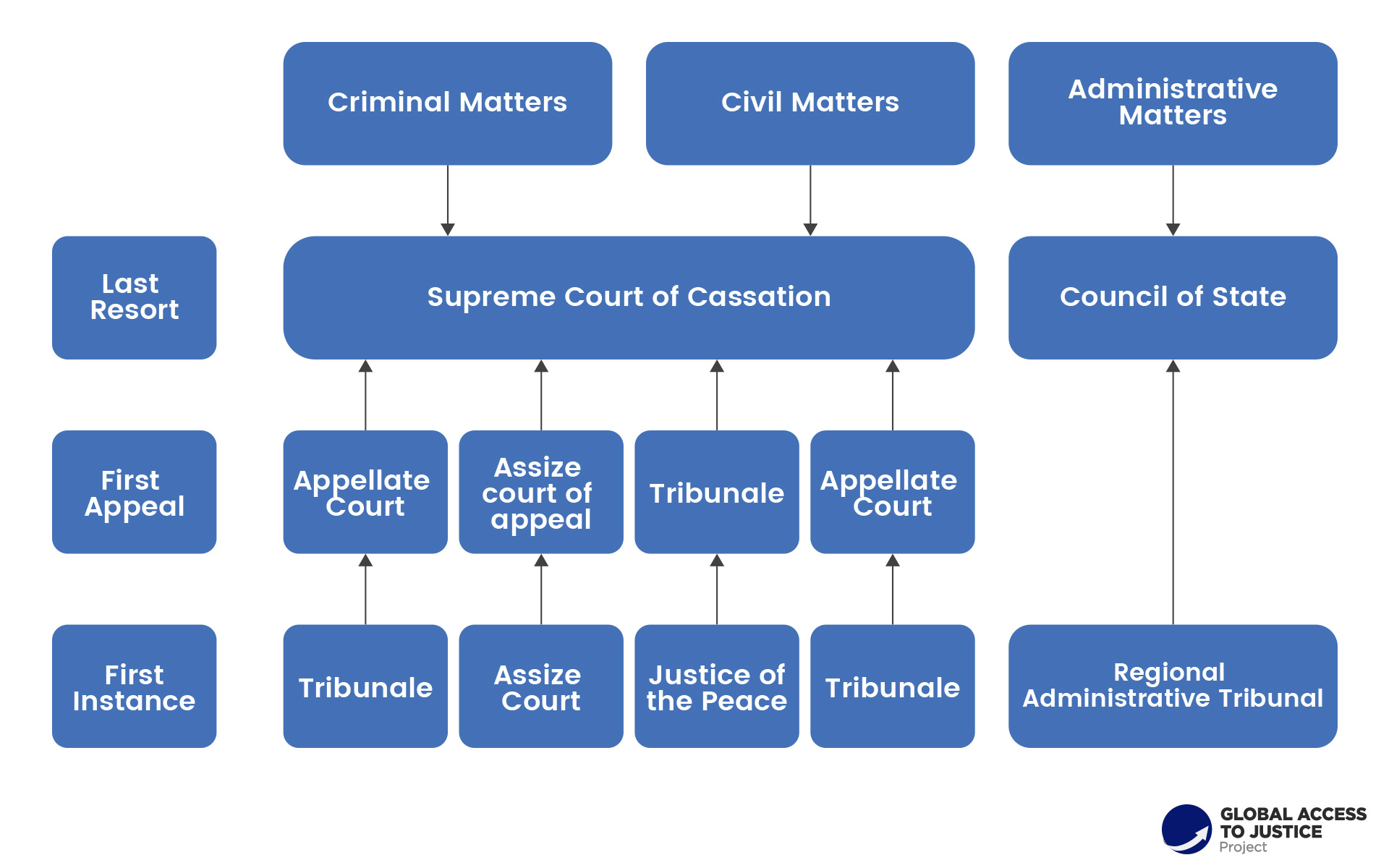

Ordinary courts have civil jurisdiction and criminal jurisdiction. The former comes into play mainly when disputes between private parties must be resolved; the latter is established with the purpose of deciding whether or not a person charged with a criminal offence is guilty, keeping in mind that in Italy criminal proceedings are instituted by a public prosecutor, who is an ordinary judge who performs a few specific functions in the framework of criminal trial and, most of all, ‘shall have the obligation to institute criminal proceedings’ (Article 112 of the Constitution).[4]

As far as ordinary courts exercising civil jurisdiction are concerned, the courts of first instance are the justices of the peace (who are honorary judges) and the Tribunali: the respective jurisdiction is determined according to the amount of money at stake or according to the subject matter. Intermediate appeals are brought to the appellate courts (Corti d’appello) and a final appeal (on points of law only) can be lodged with the Italian Supreme Court, the Suprema Corte di cassazione.

Justices of the peace and Tribunali have criminal jurisdiction as well, but other criminal courts must be listed. First of all, the juvenile courts and the juvenile divisions of the courts of appeal are the courts of first and second instance in charge of criminal offences perpetrated by minors. Assize courts (Corti di assise) are the courts of first instance that try the most serious crimes and are composed of six lay judges led by two professional judges. Beside the courts of appeal as courts in charge of intermediate appeals, there are the Assize courts of appeal (Corti di assise di appello) that hear appeals against judgments issued at the first instance level by assize courts. The supervisory courts (Tribunali di sorveglianza) and the supervisory offices (Uffici di sorveglianza) supervise the enforcement of prison sentences and the application of the law governing sentences. The Court of cassation acts as final appellate court in criminal matters, too.

According to Article 102, sec. 2 of the Constitution, ‘Extraordinary or special judges may not be established. Only specialized sections for specific matters within the ordinary judicial bodies may be established, and these sections may include the participation of qualified citizens who are not members of the Judiciary.’ The Constitution, though, makes an exception for some special courts that were already in operation when the Constitution was enacted: these courts are the administrative courts, meaning the Council of State as a single appellate court and the Regional administrative courts (Tribunali amministrativi regionali), as courts of first instance, as well as the Court of Auditors and the military courts (Article 103).

According to the evaluation of judicial systems prepared by the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) with reference to the data of 2016, in Italy the number of professional judges per 100,000.00 inhabitants is 10.6 while in the countries that are members of the Council of Europe the median is 18 and the average 21. The number of prosecutors per 100,000.00 inhabitants is 4, while in the countries that are members of the Council of Europe the median is 11 and the average 2.[5]

Chart 02. Judicial Organization in Italy

If one is inclined to follow the traditional approach taken by scholars in comparative law, one can certainly say that the Italian legal system belongs to the Civil Law family, because of his historical heritage:[6] it is a legal system in which the Roman law legacy is still detectable, even though throughout the centuries the influence of German and French laws cannot was significant, also due to the historical vicissitudes of the country that was unified only in 1861 under the Kingdom of Italy ruled by the House of Savoy. The fact that Italy is a Member State of the European Union has compelled the domestic legal system to transpose into the legislation in force institutes that are not necessarily in line with the Civil Law roots of the Italian legal culture. Furthermore, some traditional feature have declined, while new features have acquired remarkable relevance: for instance, the importance of what Italians calls ‘the doctrine’ (la dottrina, in Italian),[7] that is the work of legal scholars, is declining, while for centuries it has been considered fundamental for the proper interpretation of the law. Precedents are still not listed among the official sources of law, but court rulings (most of all, if they are issued by the Court of cassation) do have a de facto precedential value; furthermore, expressions strictly connected with the doctrine of stare decisis, such as overruling, or anticipatory and perspective overruling have been included as they are (meaning, in English) in the Italian legal lingo.

In a comparative study on the legal profession in the European Union, the situation in Italy is pictured in negative terms: fighting a rearguard battle, the Italian legal profession ‘has not undergone a fundamental transformation despite the evolution of the international market’[8] and it is stuck in ‘archaic forms of practice’[9] that, for instance, do not allow the establishment of professionals corporations. Although one may say that there is some truth in this critical assessment of Italian attorneys as a whole, it seems that the real problem with the legal profession in Italy is at present (and has been at least in the last decade) the number of lawyers. According to an official report published in June 2019,[10] the number of attorneys who are members of the Bar was 243,488 in 2018, more or less 4 attorneys for every 1,000 inhabitants. The general opinion is that Italy has too many lawyers, and evidence of that can be found in the low average income of lawyers: again in 2018, the average income was approximately €38,000.00, with sharp differences between geographical areas, so that the highest income was registered in the North of the country (specifically, in the region called Lombardy) while the lowest one in the Southern regions. According to the evaluation of judicial systems prepared by the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) with reference to the data of 2016, in Italy the number of attorneys per 100,000.00 inhabitants is 378.4 while in the countries that are members of the Council of Europe the median is 119 and the average 162.[11]

According to Article 24 of the Italian Constitution, ‘Defense is an inviolable right at every stage and instance of legal proceedings. The poor are entitled by law to proper means for action or defense in all courts’. One may argue that this principle grants the legal profession a constitutional dimension that makes it stand out from the other liberal professions and requires specific rules. As of today, the legal profession is governed by a statute passed in 2012, which replaced the regulation dating back to 1933.

The legal profession is decentralized and includes 164 local bar councils. The local bar councils are coordinated by the National Bar Council (Consiglio Nazionale Forense, in Italian), which is the highest institution of the Italian legal profession. The National Bar Council comprises 33 members, all lawyers elected within the members of the local bar councils: they stay in office for four years.

As far as the functions of the National Bar Council are concerned, they are both regulatory and disciplinary. An example of the regulatory function is the drafting and updating of the Code of Conduct for lawyers; the disciplinary function is performed acting as appellate court against the judgments issued by the district disciplinary boards at the local level for violations of the code of ethics. Judgments given by the national Bar Council are subject to a further appeal that can be lodge with the Supreme Court of cassation.

The statute governing the legal profession states that attorneys (avvocati, in Italian) shall perform their role with independence, loyalty, integrity, dignity, diligence and competence, taking into account the social importance of defense and abiding by the principles of fair and loyal competition.[12] Furthermore, attorneys shall comply with the rules laid down by the Code of Conduct, rules concerning the relationship between the attorney and his client, the opposing party and his attorney, and the court. The Code of Conduct provides for a variety of regulations having to do with the different functions attorneys can perform. It comprises 73 articles and is available in English, too.[13]

In order to become an attorney, one must earn first a full law degree (laurea magistrale a ciclo unico, this being the official denomination of the Juris Doctor degree), followed by a considerably long period of traineeship (eighteen months) under the supervision of a fully licensed attorney: during the traineeship, the prospective attorney is supposed to attend a certain number of court hearings with his mentor, and to learn how to draft legal briefs, contracts and the like.

After completion of the mandatory internship, the trainee attorney must sit for the State Bar exam, which takes place only once a year. The Bar exam includes three written tests: the candidate is expected to draft a legal opinion on a civil case, a legal opinion on a criminal case and a pleading or brief having to do with a civil, criminal or administrative case, according to the Candidate’s choice. The written tests are administered in three days in a row; candidates have eight hours to complete each test. Those who pass the written part of the Bar exam (approximately 30%) must take an oral exam on six legal subjects at the candidate’s choice. The chosen subjects, though, must include either civil or criminal law and either civil or criminal procedure: legal ethics is a mandatory subject, too.

The Italian legal profession is governed not only by domestic rules and regulations, but also by European Union normative instruments. Especially important are a few Directives that Italy has duly implemented: Council Directive 77/249/EEC of 22 March 1977 to facilitate the effective exercise by lawyers of freedom to provide services; Directive 98/5/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998 to facilitate practice of the profession of lawyer on a permanent basis in a Member State other than that in which the qualification was obtained; Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications; Directive 2006/123/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on services in the internal market (the so-called Bolkestein Directive).[14]

To the question whether the general population can afford the fees charged by practicing attorneys it is hard to give an educated answer. This author was not able to find any recent studies, reports or data able to shed light on the affordability of legal fees. Taking into account the very low annual income threshold that allows individuals to apply for legal aid (or, better yet, legal assistance paid by the public purse) one can infer that a good number of persons are expected to bear personally the expenses of turning to an attorney and, as the case may be, starting a judicial proceeding (the annual income threshold in question is just below €11,500, meaning corresponds approximately USD 12,760.00). In light of the huge number of Italian practicing attorneys, one may assume that there is competition among legal professionals, so that individuals (or, at least, those who have limited financial possibilities) may shop around in order to find a lawyer who is inclined to charge law fees in order to stay afloat: unfortunately, though, low fees are rarely met with high quality services.

Legal representation is mandatory both in civil and criminal cases. In civil cases pro se legal representation is allowed before justices of the peace, if the value at stake is below €1,100.00: it is obvious that at present nobody would go to court advancing such a small claim. In any other civil cases, the assistance of a licensed attorney is mandatory, including in the preliminary attempts at mediation (that in Italy are compulsory for quite a number of cases concerning different matters), as well as in the procedures known as assisted negotiation (another form of ADR similar to American collaborative practice, but made mandatory for claims up to €50,000.00 and when damages caused by traffic accidents are asserted). In criminal proceedings individuals must always be assisted by counsels of their choice.

Paralegals do not exist in Italy as members of a specific profession. Law offices, most of all if they consist of a large number of attorneys, have one or more legal assistants or legal secretaries who perform clerical tasks. Some legal assistants may even hold law degrees, but they do not have any particular status, neither can they represent a person in court.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal procedure

Italian criminal proceedings are governed by a code of criminal procedure approved in 1988 (the “Code”). The Code is based on an adversarial system and was finalized after a lengthy reform process that started after the fall of the fascist regime. The reform had the objective, inter alia, to conform Italian criminal procedure to the principles of the Italian Constitution and of international human rights legislation. Initially, the Code was received cold-heartedly: the then prevailing legal sentiment was still influenced by the inquisitive system previously in use and was unfavorable to any changes also due to the recrudescence of terrorist attacks and mafia-related crimes. For this reason, the Code was amended several times, with changes which were not always coherent, resulting in a Code that is now substantially different from its initial version. In brief: the first ten years from the introduction of the Code have been characterized by a clear reluctance in accepting the new adversarial system, culminated with the constitutional “due process” reform, following a few decisions issued by the Constitutional Court that essentially demolished the very principles of the new codification. The second decade witnessed the introduction of amendments to the Code, which some commentators interpreted as deriving from personal interests of political figures representing the majority party then in office (the so-called laws “ad personam”). In the last decade the discussion surrounding the Code – while also having the objective of refining the protection of fundamental rights, following repeated indications coming from European authorities – has been and still is oriented at gaining efficiency in the administration of justice, clearly slowed down by an unbearable workload. A clear sign of such inefficiency is the circumstance that a large number of proceedings terminates with the extinction of the offence due to the applicable statute of limitation, which results in a triple defeat for the justice system: while the accused person is kept under the threat of a criminal conviction for an excessive time, eventually the aim of the criminal prosecution is not satisfied, nor is the interests of the victims of the offence, while public resources are wasted in a way the is not cost-effective. Finally, it should be mentioned that the evolution of the Code during the last thirty years, as briefly summarized above, resulted in a complex system of criminal procedure that is increasingly inconsistent and follows different rules depending on the type of the criminal offence at hand. For instance, stricter rules apply for applicable measures, investigation deadlines, rules of evidence and concerning personal freedom, for terrorism and mafia-related crimes. Also, an increasing request of protection for so-called weaker subjects, in line with European directives and international conventions, resulted in the creation of specific procedural rules which apply to a large number of crimes related to personal violence.

3.1.1. Criminal investigation process

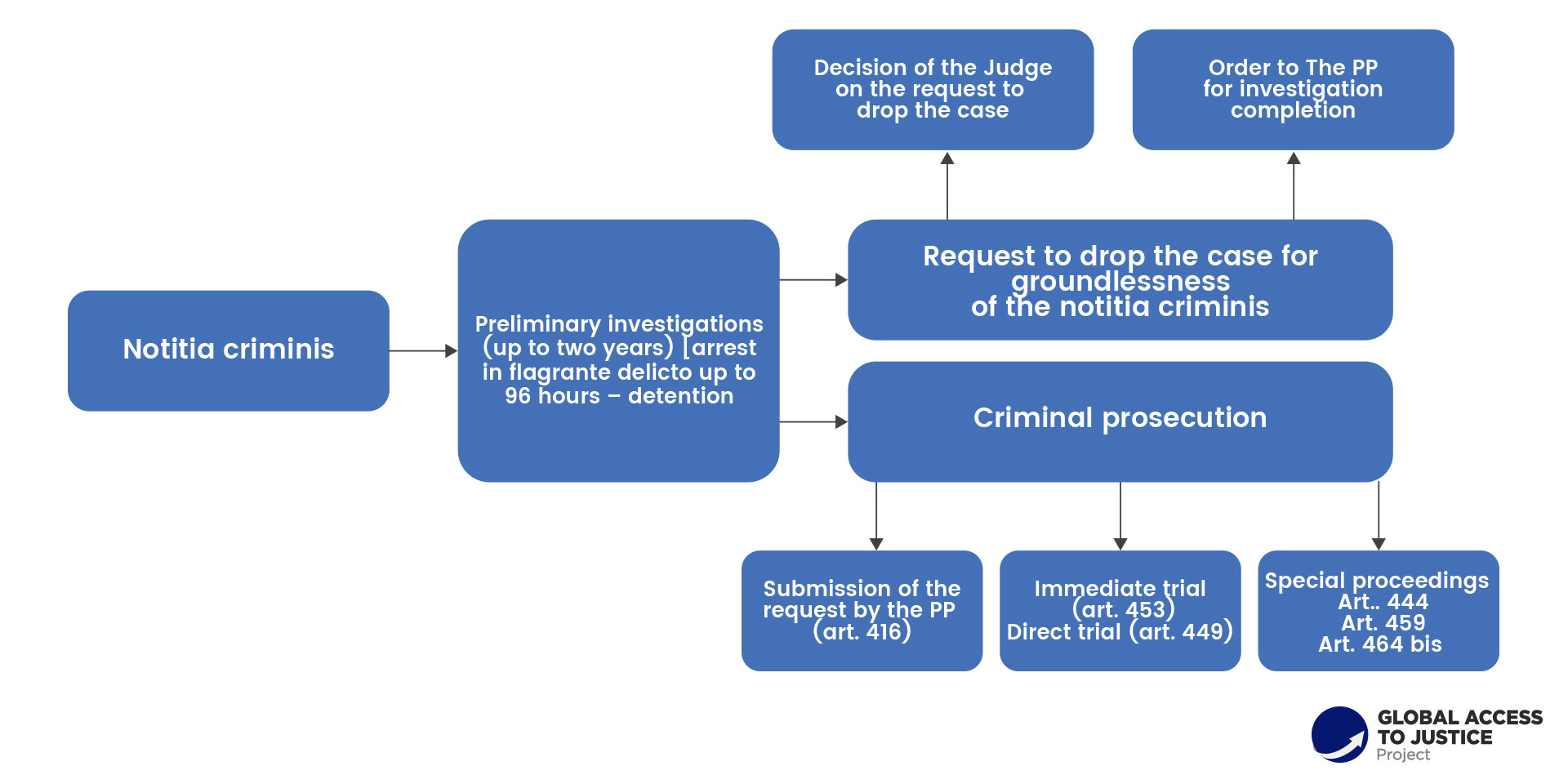

Italian criminal procedure provides for three levels of judgement. The first instance proceeding has a two-step structure contemplating first a period of investigation, which precedes the trial. The main actor in the preliminary phase is the public prosecutor (“PP”), who directs the investigations. The PP takes care personally the investigations, or, as it is more often the case for the number and quantity of the investigative acts, avails herself of the criminal police, which operates upon her delegation or within the instructions given by the PP. The principle of objectivity, which applies to the PP as a public officer, mandates that the PP must collect all the elements necessary for the exercise of the criminal prosecution, including “assessments on facts and circumstances which are favorable to the person under investigation”.

However, in order to grant equality of arms to the parties also during the investigations, the defense lawyers have been granted investigative powers that were not included in the original version of the Code, powers which are to a certain extent similar to those granted to the PP and the results of which acquire the same value recognized to the acts carried out by the PP during the investigation phase and the subsequent trial. Following the enactment of law 7 December 2000 no. 397, defense attorneys were given ample powers as regards the investigative phase: they can carry out investigations in order to search for and find elements of evidence in favor of their client ‘starting from the time when they have been granted the professional mandate’ (art 327 bis par. 1 CPP). Defense lawyers may proceed with the investigations personally or availing themselves of representatives or private investigators (provided that they are duly licensed), or experts, should a specific knowledge be required (art. 327 bis, par. 3 CPP).

The investigations start with the notice of crime, which must be recorded in an ad hoc register provided for in art. 335; investigations may last up to 18 months or two years in case of particularly serious crimes (art. 407 CPP). The person under investigation (hereinafter, also referred to as the ‘suspect’) is informed about the existence of a proceeding against her only insofar as an act must be carried out for which the presence of the defense attorney is necessary (art. 369 CPP). Therefore, it is possible that the entire investigation stage is carried out without the suspect being informed about the proceeding. However, the PP cannot exercise the criminal prosecution without first informing the suspect of the investigation in progress, so as to grant the suspect the possibility to obtain information regarding the acts carried out during the investigation, with a view to taking any actions that is useful for her defense (art. 415 bis CPP).

If during the investigation it is necessary to adopt acts which may impact on the rights of the suspect or if the suspect raises a complaint, the parties are entitled to approach a judge – the so-called preliminary investigations judge (“PIJ”) – who, being an impartial authority, is called to offer protection to the fundamental rights of the suspect and to ensure that the proceeding is carried out correctly (art 328 CPP). Among the main duties of the PIJ, in the first place there is the power to issue decisions concerning personal rights, property rights or the use of assets. For instance, the PIJ can 1) issue interim orders affecting personal freedom (art 392 CPP) or similar orders concerning assets; 2) confirm the interim measures adopted by the PP or the judicial police (art. 391 CPP); 3) authorize acts that have an impact on personal correspondence and personal domicile, like wiretapping of communications and conversations (art. 267 CPP); 4) issue orders concerning the seizure of biological samples (art. 359-bis, in connection with art. 224 bis CPP); and finally, 5) decide on the restitution of seized assets (art 263 CPP).

The PIJ also intervenes to protect the defense rights when there are assessments made on the legal capacity of the suspect to take part in a proceeding, or to decide whether to suspend the right of the suspect under arrest to consult with his attorney (art. 104 par. 3 and 4 CPP), or in situations when there is an imbalance between the position of the PP and that of the defense lawyer. In the latter case, the PIJ may for instance: i) authorize the defense lawyer during the defensive investigations to consult, receive declarations and assume information from a person who is under detention (art 391 bis, par. 7 CPP); ii) decide on the request of a defense lawyer to obtain documents from a public office (art. 391 quarter CPP); and iii) authorize the defense lawyer to enter private places or places which are not open to the public (art. 391 septies CPP). Finally, when it is necessary to anticipate the acquisition of evidence, the PIJ authorizes it and ensures that the evidence is collected in the presence of both parties, issuing instructions during the evidence collection (art. 392-402 CPP).

The PIJ has also certain duties relating to the exercise of the criminal prosecution by the PP, exercise which is mandatory. For instance, some relevant examples are the control powers granted to the PIJ as regards i) the duration of the investigations (art.406-407 CPP), ii) the conditions for the extension of the investigations (art. 414, 415, 434 CPP), and iii) the decisions made by the PP at the end of the investigations. In this regard, the PIJ decides upon both the PP’s dismissal order (art. 409) and the PP’s request for trial (art. 416 CPP). Finally, the PIJ (or the judge of the preliminary hearing, as the case might be) acts as the deciding judge in the event that the parties choose one of the so-called alternative procedures, for instance when a) the PP requests the issuance of a criminal decree (art. 461 CPP); b) the parties have agreed upon the application of a sanction (art. 444); or c) the accused person has requested an abbreviated decision, at the preliminary hearing (art. 438 and following) or after the conversion of the immediate proceeding pursuant to art. 458 or the accused person has requested the suspension of the prison sentence with probation (art. 464 bis and ff CPP.).

The suspect may be arrested by the criminal police, normally only in flagrante delicto. The PP must be informed of the arrest within 24 hours and within the following 24 hours he must request the PIJ to confirm the arrest. The PIJ has 48 hours to decide. Failure to comply with the above deadlines results in the invalidation of the arrest and the obligation to release immediately the person under investigation. The arrest may be ordered by the PP, also in the absence of an in flagrante delicto, when (1) ‘there are specific elements making it probable that the suspect may flee, also in relation to the impossibility to determine the identity of the suspect’, and (2) there are serious elements indicating that a crime has been committed. The crime must be (a) one for which the law provides for life prison or for a prison term of at least two years as minimum sentence and in excess of six years as maximum sentence, or (b) a crime concerning weapons of war, explosives, terrorism, or eversion of the democratic order (art. 384 CPP).

Restriction of personal freedom can be ordered by the PIJ upon request by the PP, pursuant to art. 274, in the following cases: 1) when there is the need to protect the acquisition of evidence; 2) in case of a probable flight of the suspect; and 3) when serious crimes are otherwise likely to be committed in light of particular factual circumstances. The suspect may challenge the arrest order (art. 309-311 CPP) and request that the arrest is re-evaluated because the underlying conditions have changed (art. 299 CPP). The terms of the arrest vary depending on the gravity of the offence and may range between 6 months and one year of imprisonment (art. 303 CPP).

Following the investigations, the PP must choose between a dismissal and the exercise of the criminal prosecution. If the PP has collected sufficient evidence in order to proceed with a request for trial, the PP must exercise the criminal prosecution. Only in the absence of sufficient evidence, that is, when the notice of the crime is found to be groundless, the PP must request the dismissal. The PP must decide based on technical requirements, since her decision cannot be based on considerations of opportunity.

Chart 03. The preliminary investigation

3.1.2. Criminal prosecution proceedings

As indicated before, the criminal prosecution is mandatory: pursuant to art. 112 Cost., upon receipt of a notice of crime, the PP must start the criminal prosecution. The PP is also the only party which is responsible for the action. The person offended by the crime has no role in such respect, except in the case of certain minor offences that cannot be prosecuted without a formal request filed by the offended party.

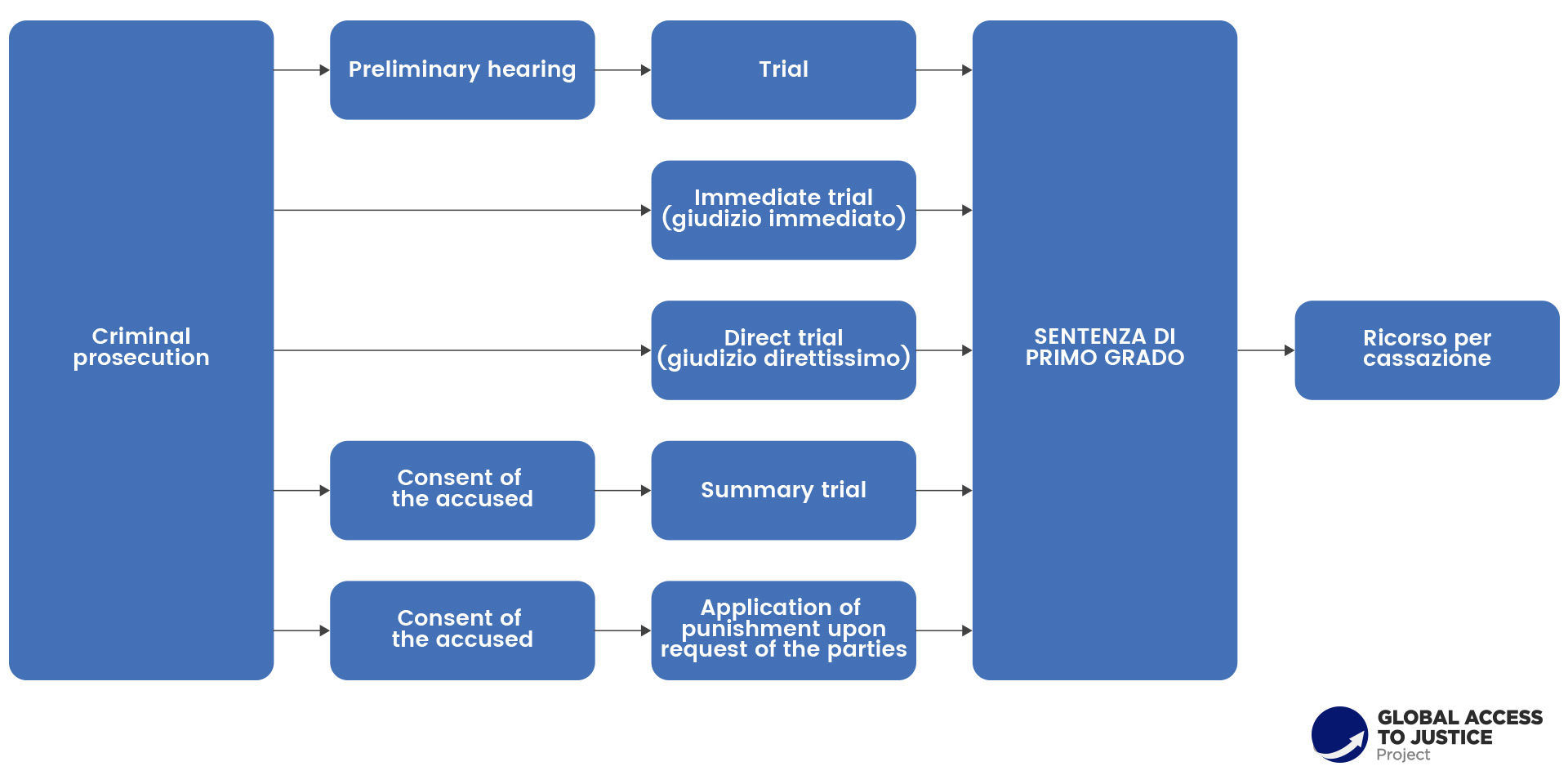

The criminal prosecution is eventually exercised with the formulation of the accusation in the forms provided for by law, in particular pursuant to art. 405, which lists the request for trial and certain alternative simplified procedures.

The request for trial (art. 416 CPP) leads to the preliminary hearing, during which the judge must evaluate whether or not the conditions for starting the trial exist. The preliminary hearing may be unnecessary when there is sufficient evidence of the crime already in the first phase of the investigations. In such case, when the relevant conditions apply, the PP may exercise the criminal prosecution, asking the PIJ to proceed with a so-called immediate trial, or taking the accused person directly before the trial judge (the so-called direct trial).

At trial, which is public and carried out according to the principles of orality and unity, the evidence is normally taken in the presence of the parties, but some exceptions exist, coherently with the provisions of art. 111 fifth par. Cost., (consent expressed by the accused person, unequivocal evidence, impossibility of collecting the evidence for objective reasons). The trial should also be carried out in compliance with the principle of concentration, thus ideally completed within one day or, if this is not possible, it should continue on the following business day: however, the current workload of courts makes this rule one of the least observed by judges.

The problem of proceedings in absentia has been resolved since 2014. After an evolution started by European case-law, which lasted for a decade, with law no. 67 of 28 April 2014, the Parliament has repealed from the Code the possibility of proceedings in absentia, except in specific cases. The judge will now proceed without the presence of the suspect when the latter, whether free or under arrest, has expressly renounced (art. 420-bis par. 1 CPP), or when there is evidence that the suspect has knowledge of the proceeding or there is a legal presumption of such knowledge (art. 420-bis par. 2 CPP). Such presumption exists when the suspect has declared or elected domicile or has been arrested, detained or under precautionary measures or has appointed a defense attorney, as well as when the suspect who is absent has received personally the notice of the hearing or there is certain evidence that the offender is aware of the proceeding or has voluntarily avoided the official notification of the proceeding or of acts thereof. When the proceeding is in absentia, the suspect is represented by her defense attorney. Depending on the gravity and the type of the crime, the competent judge will be the Court of Assize, the Tribunal (composed by either one or three judges) or the Justice of the Peace, the latter being an honorary judge who can decide only upon minor crimes.

The PIJ (or the judge for the preliminary hearing, depending on the circumstances) is the trial judge for alternative procedures such as the simplified trial (art. 438-443 CPP), the ‘settlement procedure’ (art. 444-448 CPP), the criminal decree (art. 459-464 CPP), and the suspension with probation (art. 464 bis-464 novies CPP). These are procedures which imply the granting of certain benefits against concessions by the accused person. Generally, a material reduction of the sentence and additional benefits are granted: for instance, the judge cannot apply ancillary sanctions and precautionary measures, the accused person will not pay the costs of the proceeding and will be entitled to the extinction of the crime if certain terms are met; the decision will not be mentioned in the judicial records. All that, if the accused person waives certain defense rights of hears.

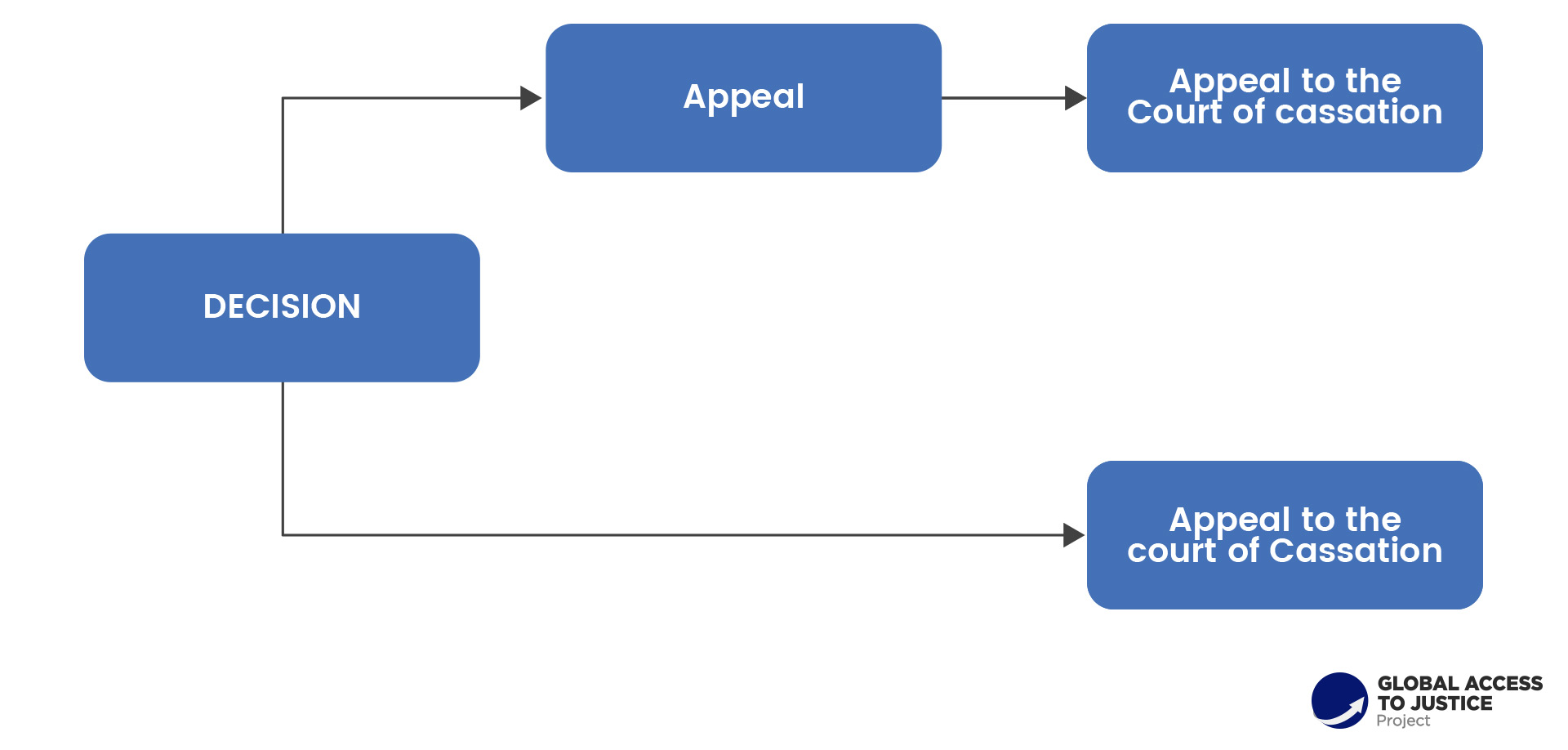

Following the first instance decision, the offender and the PP (and, under the circumstances, also the damaged parties exercising an action for damages, as well as the party responsible for damages if different from the accused person), have the right to file an appeal against any types of decision. The decision issued on appeal can be challenged through a motion to the Court of cassation, which can be filed solely for issues of law, for the reasons listed in art 606 CPP.

The right to appeal is granted in very ample terms and the decision becomes binding and final only when no further challenges other than the so-called revision are available to the convicted person. The rules concerning the right to appeal criminal decisions are the principal aspect that the government will have to take into account in the near future. It should be noted that the practical experience shows an abuse of appeals by convicted persons, who aim at delaying the enforcement of the conviction and often, with the passing of time, the extinction of the crime due to the rules on the statutes of limitation, and therefore impunity. The fact that up to 70 per cent of the appeals brought to the Court of cassation are declared inadmissible confirms that many challenges are abusive.

One should also note that even after decisions become final and binding, the convicted person can start a revision proceeding, meaning an extraordinary action that can be resorted to when new facts contrary to the findings of the proceeding emerge or when the decision must be made in agreement with a final judgment issued by the European Court of Human Rights, pursuant to art. 46 par. 1 ECHR.

There are no duration limitations applicable to the criminal proceeding but, as already observed, it happens often that the proceedings ends with a dismissal due to the extinction of the crime: the Code provides that the accused person cannot be convicted when a certain number of years have elapsed from the time when the crime was perpetrated (it is irrelevant when the commission of the crime becomes known to the authorities).

During the proceeding, the offender can be subject to precautionary arrest for the same reasons described above with respect to the investigations phase (art. 273 and art. 274 CPP). Limitations to the duration of the arrest are provided for, depending on the gravity of the crime, for each phase of the proceeding (art. 803 par. 1). Furthermore, an overall maximum term is contemplated, also depending on the gravity of the crime: the accused person will have the right to be released if the proceeding is not completed within 2, 4 or 6 years, depending on the crime (art. 303 par. 4 CPP).

Chart 04. Trial and special proceedings

Chart 05. Appellate Remedies

3.1.3. Italian criminal procedure and due process

The Italian criminal procedure is based on the principle of ‘due process of law’: mandatory exercise of the criminal prosecution, independent and impartial judges, presumption of innocence and an inviolable right of defense at any stage of the proceeding are some of the principles adopted by the Code, and also embedded in our Constitution.

Guarantees of context (right to defend oneself through legal assistance, equal rights between the PP and the defense lawyer, impartiality of the judge and reasonable duration of proceedings) and rights essentially corresponding to the basket of rights provided for by art. 6 par. 3 ECHR are specifically granted to the accused person. The Code provides that the person who is accused of a crime in the shortest possible time shall be informed, on a confidential basis, of the nature and the reasons of the accusations raised and be granted the time and the conditions which are necessary for preparing her defenses, and have the right before the judge to question or have questions raised to the persons making declarations against her and to obtain the calling and the interrogation of the persons to her defense with the same rights and conditions as the PP, and the acquisition of any other evidence in her favor; to be assisted by an interpreter if she does not speak or understand the language spoken within the proceeding. Besides, the Italian Constitution and the Code must be read in conjunction with the provisions of international conventions, which are an integral part of the Italia legal system.

In any case, it is true that, notwithstanding the ample guarantees that characterize our system, in practice the Italian criminal proceeding is still too slow. For this reason, proposals for the reform of criminal procedure insist on measures of decriminalization, as well as on measures for procedural simplification and for the search of alternatives to criminal prosecution. The reform of appeal rights is another area to be taken into consideration for the future, for the reasons mentioned above.

3.2. Civil Procedure

Civil procedure is mainly regulated by the Code of civil procedure, which dates back to 1940 and entered into force in 1942.[1] One may wonder whether the fact that the Code was adopted during the Fascist era had a strong bearing on its content and, as a matter of facts, some scholars believe that the Code upheld an authoritarian model of civil justice, centered on a strong and powerful judge, the real ‘master of the game’, while the parties played a secondary role. Whatever the drafters of the original text of the Code had in mind, it is necessary to emphasize that the Code has gone through countless amendments and additions that only its appearance (that is to say, for instance, its division into four books) has remained the same. A variety of judicial procedures that can be loosely qualified as belonging to what is conventionally called ‘civil justice’ are located outside the code, being provided for by special statutes, many of which carry their label of origin in European law, either directly applicable in the Member States or to be implemented via domestic statutes. Last but not least, the advent of the Constitution (in 1948) and the active involvement of the Constitutional Court in repealing quite a number of procedural rules deemed at odds with fundamental principles have established the unwritten rule according to which procedural rules (as well as substantive ones) must be given a constitutionally oriented interpretation by the courts that are supposed to apply them.

As explained above, at the first instance level civil and commercial jurisdiction pertains to either the justices of the peace or to the Tribunali. Justices of the peace have jurisdiction when the value at stake is below €5,000.00, but the threshold is higher (€20,000.00) when damages caused by traffic accidents are sought. Justices of the peace have also a limited subject matter jurisdiction. Tribunali have jurisdiction over cases exciding the threshold mentioned above and exclusive jurisdiction over specific matters (e.g., personal status and family matters, as well as enforcement procedures). Complex rules have to be applied in order to determine the proper venue so as to choose the court where to initiate litigation. Under Italian law, jurisdiction (giurisdizione) and venue (competenza territoriale) are important issues on which the court can rule at the outset of litigation, causing – as the case may be – the dismissal of the action.

Within each Tribunale cases are heard either by a single judge or by a three-judge panel. Nowadays, the majority of cases are dealt with by a single judge; in the small number of cases entrusted to a three-judge panel (e.g., cases arising out of bankruptcy law or the law of decedent’s estate), one judge is in charge of the whole development of the proceeding and reports to the other two members of the panel with a view of issuing the final judgment.

Before the Tribunali, the ordinary procedure can be divided into three stage: the introductory stage; the evidence taking stage; and the decision stage.

As far as the introductory stage is concerned, a civil action begins when the plaintiff serves a statement of claim on the defendant. The statement of claim (in Italia, atto di citazione) must include a list of mandatory elements, such as the cause of action and the material facts supporting the cause of action, as well as the relief sought, and the evidence and the documents that the plaintiff intends to use to prove his allegations. In his answer, the defendant must ‘put forward all his defenses and take a stand on the material facts advanced by the plaintiff in support of his cause of action’ (Article 167, sec. 1 of the Code of civil procedure, my translation). The answer must list the evidence and the documents that the defendant intends to use in order to oppose the plaintiff’s contentions.

Concepts such as pre-trial phase, pre-trial discovery and trial are alien to the language of Italian civil procedure, since adjudication develops along a variable number of hearings that are self-contained ‘episodes’, and have no continuity at all, if only because hearings, as a rule, are far too spaced out. The first hearing is particularly important, since at this hearing the parties are entitled to ‘line up the shot’ by clarifying and modifying their allegations. At the same hearing the court rules on the admissibility of the evidence offered by the parties.

As far as the evidence taking is concerned, it is worth emphasizing that in principle the court must rely only on the evidence offered by the parties in support of the factual allegations they have made in their pleadings. This general rule (laid down by Article 115, sec. 1 of the Code) has some exceptions that apply only insofar as there is a legal rule granting the court the power to take evidence ex officio. This happens for instance in the procedure followed in labor cases, as well as in certain non-contentious proceedings. [2]

Evidence must be not only admissible, but also relevant for the case at hand. Evidence is relevant when it has a logical connection with the facts in dispute, so that it allows to establish whether or not these very facts are true.

One may say that the probative weight of each piece of admissible evidence can be placed in a theoretical hierarchy: at the top there is documentary evidence and, in particular, the so-called public deeds (atti pubblici, in Italian), which are documents drafted and signed by notaries public or other public authorities entrusted with the power to grant ‘public faith’ to the documents they draw up. The probative value of public deeds, private writings and other documents are governed by complex rules that are common to the majority of continental European legal systems having roots in the Civil Law tradition. Out of curiosity, one must mention the fact that among admissible evidence the Italian laws in force still list the oath and the confession.[3] The new forms of evidence connected with the development of modern IT are subject to regulations laid down by special statutes.

Testimony refers solely to statements made in court by third parties (witnesses): this means that neither the statements made by the parties nor expert opinions are considered testimony. As far as experts are concerned, they are considered auxiliary officers of the court.

According to Article 116, sec. 1 of the Code, ‘The court must evaluate the evidence in accordance with its prudent judgment, except as otherwise provided by the law’ (my translation). Scholars emphasize the adjective ‘prudent’ evaluation, in order to signify that a free evaluation of evidence must not cross into an arbitrary or capricious assessment, in light of the fact that courts are bound to expound on the reasons that led them to accept or reject the evidence in the judgments they issue. Exceptions to the rule just mentioned concern what Italians call ‘legal evidence’ (prova legale in Italian): legal evidence is evidence whose probative value is pre-determined by the law. ‘Legal evidence’ includes in general certain types of documentary evidence, party admissions, and conclusive presumptions.

When the evidence taking stage is over, the parties are expected to lodge with the court their final briefs (in Italian, comparse conclusionali and memorie di replica), in which they summarize all the factual and legal arguments that the parties want the court to take into account. Oral argument takes place rarely and only if a party so requests.

The judgment is immediately enforceable (which means, in case of a money judgment, that the creditor can begin the appropriate enforcement procedure). Italian decisions must always lay down the facts in dispute and the legal principles applied by the court in order to arrive at the judgment, since one of the canons of due process is, according to the Italian Constitutions, the rule according to which ‘All judicial decisions shall include a statement of reasons’ (Article 111, sec. 6).

Even when the case is decided by a three-judge panel, the only opinion that counts and has legal value is the majority opinion. Neither concurring nor dissenting opinions are contemplated by Italian law.

As far as the procedure before the justices of peace is concerned, the pattern followed is more or less the same as the procedure before the Tribunali with a few simplifications that do not seem worth mentioning.

With reference to case management, one must emphasize that the concept of case management is alien to Italian civil procedure. Italian litigation still advances through an endless series of hearings scattered over an unpredictable time period, so that it is fair to say that the concept of a real preparatory stage is wishful thinking, devoid of any practical application. That being the situation, it should not come as a surprise that judicial case management is terra incognita. On the contrary, what is surprising is the fact that, according to the Code of Civil Procedure, the court ‘is entrusted with all the powers necessary for the swift and fair development of the proceeding’, including the power ‘to set deadlines for the completion of procedural steps’ (Article 175, sections 1 and 2; my translation). Furthermore, the court also has the power to impose sanctions on the parties and their lawyers when they have breached the duty to conduct litigation with fairness and integrity (Article 88). Therefore, it is clear that, according to the procedural rules in force, Italian courts could resort to at least minimal case management. In reality, though, that does not occur. essentially because caseloads are very heavy and courts are understaffed. The combination of these two curses that the Italian justice system is unable to dispel makes it impossible for the judges to properly study each case, as would be necessary for a sound exercise of case management powers. There have been recent attempts at improving the situation, for instance through the establishment of the so-called ‘ufficio per il processo’ (which can be roughly translated as ‘office for the proceeding’), which increases the judicial staff by the addition of law clerks (typically, young law graduates) or lay judges and other persons who are supposed to help judges navigate the sea of documents, briefs and other kinds of papers that make up the courts’ dockets and to decipher the mysteries of online justice (a recent feature of Italian civil justice).

Beyond the practical realities there are essentially ideological barriers preventing any attempt at reforming the Code of Civil Procedure in the direction of envisioning a structured and non-episodic case management, as well as the possibility for the court to adjust the procedure according to a standard of proportionality. According to a widespread school of thought, to grant judges broad case management powers would mean to inject an authoritarian note into civil procedure. In order to understand this curious idea, one should revisit the history of the Code of Civil Procedure in force. The Code was adopted in 1940, and the fact that courts were entrusted powers allowing them to play an active role in the development of proceedings was later seen as the sign of a ‘fascist’, authoritarian approach to litigation. That is why any idea of granting more powers to courts is often met with a good measure of skepticism, if not open hostility. As often is the case, misconceptions stem from ignorance, and even in the case of the Code and the powers granted to courts an accurate reading of the Report accompanying the original text of the Code would be illuminating. The Report shows how the drafters of the Code anticipated ideas that would become popular much later. In their concept of the dynamics of civil justice, the divide between an inquisitorial model of adjudication and a proceeding molded by the judge according to the specific needs of the case at hand was clear. To dictate a single, rigid procedure applicable to each and any case – the Report reads – neither satisfies the need for an accurate finding of the facts (which is necessary most of all in complex cases) nor does it grant an expedited disposition of cases (which is a need particularly felt when a case is simple or requires an urgent resolution). Therefore, it is necessary to organize the development of adjudication according to the principles of adaptability and flexibility: the court, assisted by the parties, should adapt the procedure to the specific features of the case, so as to obtain the highest possible level of procedural economy.

Even though the advent of case management in Italian civil procedure cannot be foreseen at least in the near future, mention has to be made of a relatively new type of first instance proceeding that was introduced in 2009 and advances, modestly, the cause of a managerial treatment of cases. Reference here is to the so-called ‘summary proceeding’ (in Italian, procedimento sommario di cognizione) that can be chosen by the claimant if certain requirements are met. From the point of view of judicial case management, the summary procedure is very interesting, since the court, ‘taking into account the introductory pleading and having heard the parties, can decide how the case will develop, dispensing with any formalities that are not essential to safeguarding the due process rights of the parties’ (Article 702 ter, sec. 5 of the Code; my translation). Therefore, the court can adapt the procedure to the needs of the case with a flexible approach that is the exact opposite of the rigid approach typical of the structure of the ordinary first instance proceeding. Unfortunately, the summary proceeding has not been very successful in practice, for a variety of reasons that cannot be explained here and now. In spite of that, a variety of bills pending before the Parliament for the (umpteenth) reform of the Code of Civil Procedure provides for a generalization of the summary proceeding, which would become the basic model of proceedings before first instance courts.

As regards provisional or interim remedies (in Italian, provvedimenti cautelari), the Code of civil procedure, as well as a number of special statutes, provide for different types of provisional remedies. According to a traditional, but still sound explanation, three possible situations justify the request for a provisional measure: when it is highly foreseeable that a judgment will remain unsatisfied; when it is necessary to protects the rights of the parties while an ordinary proceeding is pending; and when there is the need to preserve evidence, which could go missing or be destroyed or, in general, could become unavailable[4]

Interim measures can be requested before the commencement of a civil law suit (in Italian, we talk about provvedimenti cautelari ante causam) or when litigation is pending. The procedure is governed by a set of rules laid down by the Code of civil procedure: these rules are known as ‘the uniform procedure for interim measures’ (my free translation of the Italian ‘procedimento cautelare uniforme’: Articles 669-bis – 669-quaterdecies of the Code). On their turn, these rules are supplemented by other rules that govern individual provisional measures.

It is conventional to distinguish between protective measures and anticipatory measures. The formers are aimed at preserving the status quo during the development of judicial proceedings or at preserving property in order to guarantee the satisfaction of a future money judgment. The latter anticipate the effects of a final judgment. Protective measures always require an action on the merits to be instituted within a specific deadline: should this condition not be satisfied; the measure automatically loses its effects. Differently, anticipatory measures do not need the support of a judgment on the merits; their effects survive whether or not an adjudication on the merits ensues, even though they cannot be relied upon as a final judgment that settles the issues in dispute with res judicata authority.

Interim measures are specific, meaning that each one is available only if certain requirements are met. In spite of that, when there is a danger of imminent and irreparable injury and no specific interim measures are available, the court may grant an ‘urgent measure’ (provvedimento d’urgenza, in Italian: Article 700 of the Code) whose content can be shaped so as to ensure in advance the future effects of a decision on the merits. That said, for the granting of all provisional measures two requirements must be met: the fumus boni juris, meaning that the applicant must show a credible cause of action, and the periculum in mora, which exists when it is reasonable to believe that, while the applicant is waiting for a judgment on the merits, the right for whose protection the provisional measure is sought will be subject to irreparable damage.

Italy has a chronic problem with the excessive length of judicial proceedings, whether civil, criminal or administrative. At July 1, 2019, a total of 3,425 Italian applications were pending before the European Court of Human Rights:[5] a high percentage of applications concerns the violation of Article 6, sec. 1 of the ECHR insofar as it provides for a reasonable duration of judicial proceedings. The extent of the problem is such that it is not possible to mention the countless Interim Resolutions issued by the Committee of Ministers at the Council of Europe, neither does it make any sense to elaborate, on the one hand, on the causes of the problem and, on the other hand, on the various attempts made through law reform with a view to expediting the pace of justice. A few excerpts from selected judgments can elucidate the situation better than a scholarly recount.

In Scordino v. Italy (2006),[6] the Court said:

‘It feels it important to point out that the reason it has been led to rule on so many length-of-proceedings cases is because certain Contracting Parties have for years failed to comply with the “reasonable time” requirement under Article 6 § 1 and have not provided a domestic remedy for this type of complaint.

The situation has worsened on account of the large number of cases coming from certain countries, of which Italy is one. The Court has already had occasion to stress the serious difficulties it has had as a result of Italy’s inability to resolve the situation. It has expressed itself on the subject in the following terms:

“The Court next draws attention to the fact that since 25 June 1987, the date of the Capuano v. Italy judgment (Series A no. 119), it has already delivered 65 judgments in which it has found violations of Article 6 § 1 in proceedings exceeding a “reasonable time” in the civil courts of the various regions of Italy. Similarly, under former Articles 31 and 32 of the Convention, more than 1,400 reports of the Commission resulted in resolutions by the Committee of Ministers finding Italy in breach of Article 6 for the same reason.

The frequency with which violations are found shows that there is an accumulation of identical breaches which are sufficiently numerous to amount not merely to isolated incidents. Such breaches reflect a continuing situation that has not yet been remedied and in respect of which litigants have no domestic remedy.

This accumulation of breaches accordingly constitutes a practice that is incompatible with the Convention.” (see Bottazzi v. Italy [GC], no. 34884/97, § 22, ECHR 1999‑V; Ferrari v. Italy [GC], no. 33440/96, § 21, 28 July 1999; A.P. v. Italy [GC], no. 35265/97, § 18, 28 July 1999; and Di Mauro v. Italy [GC], no. 34256/96, § 23, ECHR 1999-V)’.

More recently, in Zullo v. Italy (2006), the Court emphasized again that

‘[…] A domestic remedy has been introduced [in the Italian law in force]. However, that has not changed the substantive problem, namely, the fact that the length of proceedings in Italy continues to be excessive. The annual reports of the Committee of Ministers on the excessive length of judicial proceedings in Italy (see, inter alia, CM/Inf/DH(2004)23 revised, and Interim Resolution ResDH(2005)114) scarcely seem to reflect substantial changes in this area. Like the applicant, the Court does not see how the introduction of the Pinto remedy at domestic level has solved the problem of excessively lengthy proceedings. [Omissis]. The Court emphasises once again that Article 6 § 1 of the Convention obliges the Contracting States to organise their legal systems so as to enable the courts to comply with its various requirements. It wishes to reaffirm the importance of administering justice without delays which might jeopardise its effectiveness and credibility. Italy’s position in this regard has not changed sufficiently to call into question the conclusion that this accumulation of breaches constitutes a practice that is incompatible with the Convention.’[7]

The domestic remedy mentioned in Zullo v. Italy is a special procedure provided for by statute no. 89 of 24 March 2001 with a view to granting litigants the right to claim damages (before appellate courts) in case of excessively lengthy court proceedings. A reform of the procedure in 2012 set the maximum length of proceedings at six years. Unfortunately, the so-called ‘Pinto remedy’ has not been successful: to the contrary, the cure has turned out to be worse than the disease, so to say, since throughout the years the statute has brought about additional litigation and huge costs for the national budget.

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

Italy has unconditionally embraced the gospel of ADR. The reasons are not ideological, but only practical: ADR schemes carried with them the promise of a reduction in the heavy courts’ caseload. The belief that ADR could save Italian civil justice from collapsing under an over-growing number of judicial proceedings was so strong that a few ADR methods were made mandatory, that is to say that they are compulsory steps that parties must take prior to being allowed to appear before the court. This is the case of mediation and assisted negotiation. As far as mediation is concerned, the Italian legislators provided for it in 2010 via implementation of EU Directive 2008/52/EC on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial cases. From the outset, mediation was made mandatory in a variety of cases; due to a strong opposition from lawyers’ associations, the rules on the duty to attempt mediation before regaining the right to access the court ended up before the Constitutional Court. Mandatory mediation was declared at odds with the Constitution, but only for a formal quibble, which allowed the Parliament to reinstate mandatory mediation soon afterward.[8] Therefore, at present, the Italian legal system provides for three types of mediation: voluntary mediation, devoid of any practical relevance; mandatory mediation, in a long list of disputes concerning matters such as property rights, trust and real estate, landlord and tenant disputes, banking and financial contracts, just to mention a few examples; and mediation ordered by the court at any stage of the proceeding, not only before a court of first instance, but while the appellate procedure is pending as well. A peculiar feature of Italian mandatory mediation is that parties must appear in front of the mediator with their own attorneys. In other words, legal representation is conceived as always necessary and not optional, in spite of the conventional wisdom according to which in mediation parties should work together so as to try themselves to put an end to their dispute, working out an agreement that is suitable for both.

Assisted negotiation vaguely resembles the American collaborative law, but a fundamental difference must be emphasized. The attorneys assisting the parties during the negotiation do not face any ethical impediments preventing them from representing the same parties in court, if the negotiation fails. This means that they have no incentives to work so as to help the parties reach a settlement. Assisted negotiation is mandatory when damages caused by traffic accidents are claimed and for any case in which the amount at stake is above €50,000.00.

Other ADR schemes have been introduced though the implementation of another European Directive, meaning Directive 2013/11/EU on alternative dispute resolution for consumer disputes. These schemes are specifically designated to simplify access to justice for consumers and users; along the same lines, one must mention the availability of a special online platform for the disputes arising out of transactions that took place in the so-called ‘marketplaces’: the platform has been established by EU Regulation no. 524 of 2013. Finally, a number of special statutes addressing specific subject matters (telecommunications, tourist services, just to offer the reader a couple of examples) provide for either voluntary or mandatory attempts at conciliation or mediation, not to mention the special ADR bodies established for the amicable resolution of disputes in the domain of banking law, insurance, derivatives, commercial banking, capital markets and investment management. One may say that probably even in the field of ADR methods a serious simplification would be necessary: as they say, ‘less is more’, even in the field of access to justice, when ‘more’ only means a variety of ADR methods that overlap and make it difficult for ordinary people to figure out which one is the best suited for their needs. [9]

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal process

No special, simplified procedures exist for the resolution of small claims. In 2014 new rules for the separation of spouses and the divorce were introduced, allowing the parties to resort to a semi-administrative procedure that does not contemplate, in principle, any judicial involvement.

In exceptional circumstances as provided for by specific rules, courts can issue decisions that are not based on the law in force, but on principles and criteria that take into account the peculiar aspects of the case at stake. The Italian expression by which this hypothesis is identified is known as ‘giudizio di equità’. The term ‘equità’ is difficult to translate, since the English ‘equity’ is only an acoustic similarity. Often, in order to explain what ‘equità’ means Latin expressions are used, such as (judgment) ‘secundum conscientiam’ or (judgment) ‘ex aequo et bono’. In any event, the only significant cases decided dispensing with the applicable legal rules are those decided by justices of the peace when the amount at stake does not exceed €2,500.00 (Article 113 of the Code of civil procedure).

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

The right for everyone to access to court, to receive legal assistance and a fair trial is granted in Italy by virtue of both international and national law.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), in his Article 8 grants the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted to everyone by the Constitution or by law and, in Article 10, it grants a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal for everyone, in full equality, in the determination of his right and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.

The European Convention on Human Rights (1950) is more precise, recognizing not only an equal right in accessing the courts and the right to an effective remedy in case of violation of the Convention (article 13), but also the right to “legal assistance of his own choosing or, if he has not sufficient means to pay for legal assistance, to be given it free when the interests of justice so required” (article 6 c): this principle was originally limited only to criminal cases, but later on it was extended to non-criminal cases as well by the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, inferring it from the right to a fair trial. More or less the same is established also in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966, Article 14, particularly para. 3 d).

The Charter of Fundamental Rights on Freedoms of the European Union (2000, revised in 2007, and binding from 2009) grants a fair trial and the right to legal aid, which “shall be made available to those who lack sufficient resources in so far as such aid is necessary to ensure effective access to justice”, without making any distinction between criminal and non-criminal cases (Article 47).

The implementation and enforcement of all these international treaties takes place primarily at the national level. In particular, Article 4 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) requires EU Member States to take appropriate measures in order to ensure the fulfillment of obligations arising out of EU law. This is the so-called principle of sincere cooperation. Additionally, Article 19 of the TEU requires Member States to provide sufficient remedies that guarantee effective legal protection in the fields covered by EU law.

From this point of view, the Italian Constitution (1948; art. 111 was changed in 1999) has implemented all these principles in two fundamental articles, one in part I (Rights and duties of citizens) and the other in Title IV (The judicial branch): the first one, that is, Article 24, grants the right to take action in court for everyone who needs to protect his right sunder civil and administrative law; it ensures the right of defense in every stage and instance of legal proceedings and provided that those who are ‘not wealthy enough’ could have proper means for action or defense before all courts[1]. The second one, Article 111, establishes the right to a fair trial and explains in details what this right means: ‘Jurisdiction shall be implemented through due process regulated by law. All court trials shall be conducted with adversary proceedings and parties shall be entitled to equal conditions before a third-party and impartial judge. The law shall provide for a reasonable duration of trials. In criminal law trials, the law shall establish that the accused be promptly and confidentially informed of the nature and reasons of the charges and be given adequate time and conditions to prepare a defense. A defendant shall have the right to cross-examine witnesses for the prosecution, or to have them cross-examined before a judge; examine witnesses for the defense in the same conditions as the prosecutor; and the right to produce any evidence for the defense. The defendant shall be entitled to the assistance of an interpreter in the case such defendant cannot speak or understand the language in which court proceedings are conducted. The formation of evidence in criminal law trials shall be based on an adversarial process. The guilt of the defendant may not be established on the basis of statements by persons who have willingly refused cross-examination by the defendant or the defendant’s counsel. The law shall regulate the cases in which the formation of evidence may not occur in an adversarial process, with the consent of the defendant or owing to verified objective impossibility or proven illicit conduct. All judicial decisions shall include a statement of reasons. Appeals to the Court of Cassation in cases of violations of the law shall always be allowed against sentences and against measures affecting personal freedom pronounced by ordinary and special courts. This rule can only be waived in cases of sentences by military tribunals in time of war. Appeals to the Court of Cassation against decisions of the Council of State and the Court of Accounts are permitted only for reasons of jurisdiction’[2].

Nevertheless, as observed recently, ‘Italy is a country where the conflict between law in books (particularly in the Fundamental Charter) and law in action is extremely acute[3].

First of all, there was and there is not a real political debate around the subject of access to justice: no mentions of it in parliamentary debates or in political party manifestos, with the only exception of the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle)[4], whose political agenda includes some minor reform proposals in the fields of legal costs, ADR systems, legal aid and class actions[5].

The lack of political debate results in the fact that in the last twenty years the majority of legislative provisions related to access to justice were merely the implementation of European directives: for example, this is the case with the statute no. 89 of 2001 (the so-called Legge Pinto), that provided for a remedy to resort to in case of unreasonable length of judicial proceedings and was passed in response to the many cases that in the previous years had been lodged against Italy with the European Court of Human Rights; it is also the case with the Legislative Decree n. 28/2010, that introduced in Italy civil mediation, following EU directive 2008/52/CE and with Legislative Decree n. 130/2015, that introduced ADR for consumers, following EU directive 2013/11/EU.

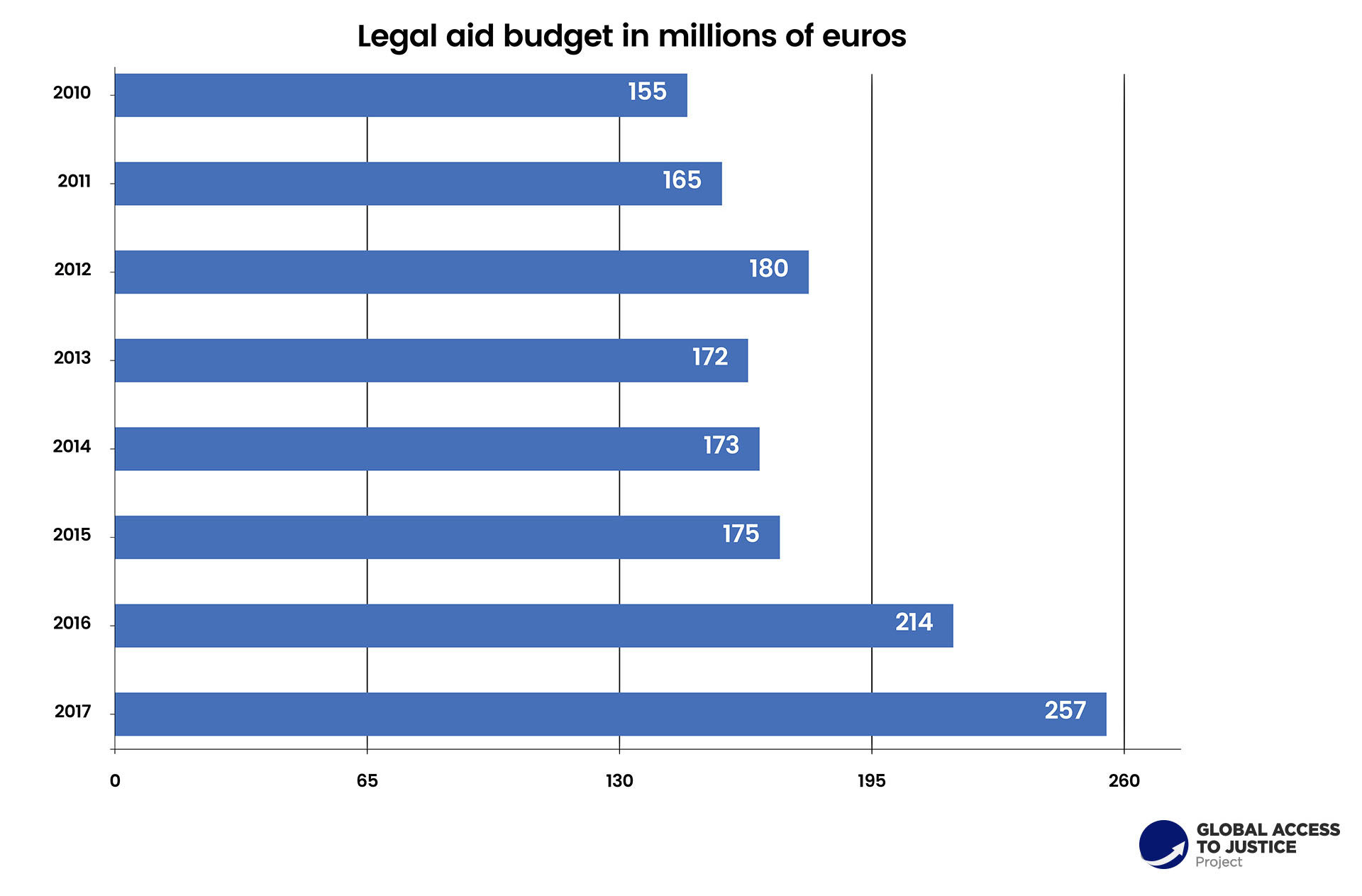

This kind of emergency legislation was also behind the reformation of legal aid in 2001 and 2002 (consolidated law no. 115 of 2002, on litigation costs, Articles 74190), because private lawyers, well represented in parliamentary chambers, wanted to prevent the possible introduction of a staff attorney model (see 5.1) and so decided to promote a reformation that could replace a liberal pro bono model with a direct judicare model.

The result of all this is that the regulatory framework is fragmented, unclear and deficient, because there are many other fields relevant in granting access to justice, that are not covered by any provisions: for example, in real life every legal need, whether it is a right to defend or a contract to be draft, due to the lack of legal alphabetization in the population requires the assistance of a lawyer. This implies a fee for the advice, which is not covered by the legal aid system[6]. Also, many kinds of ADR solutions, like mediation and assisted negotiation, when not provided as mandatory steps before accessing the courts[7], are not covered by legal aid provisions; for people who cannot afford a lawyer, these limitations undermine the general purpose of ADR, that is to avoid a trial as a mean to resolve the dispute more quickly and without the expenses of a judicial proceeding.

A public debate around access to justice problems does not really exist, and the scholarly debate is not so heated: if we except a general study of 2016 in which Alessandra Osti tried to evaluate the constitutional and European problems of the access to justice in Italy, comparing to those of other countries[8], very few other studies present a detailed examinations of the general problems of granting access to justice[9]. Some do so from the point of view of European law[10], while others compare the approach followed by different countries[11], but in general they deal only with specific issue in the field of access to justice, such as legal aid[12] or ADR[13].

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

The Italian State began his history officially as a Kingdom on 17 March 1861, after a cultural and political process of constructing the national identity known as ‘Risorgimento. It aimed at overcoming the political fragmentation of the country into many regional States and to expel foreign powers out of the Peninsula, for instance the Austrian Empire, which ruled the Lombardo-Veneto. Therefore, this process developed through a series of war events, led by the Savoy dynasty (which until then had governed the regional Kingdom of Sardinia), or conducted somehow in agreement with it (for example, the famous expedition of the “Mille” led by Giuseppe Garibaldi). All these efforts finally brought about the creation of a new state entity in 1861, even though the goal of completing national unification was achieved only with the conquest of the Papal State in 1870 and with the annexation of Trento and Trieste in 1918.

The sudden formation of the new State required a considerable effort to harmonize the legislation in force in the pre-unification States: for reasons of speed, the strategy was often limited to extend the Sardinian-Piedmont legislation to the other territories, with the modifications that were deemed necessary from time to time. At first, this led to apply to the entire national territory the judiciary existing in the Kingdom of Sardinia, which also included some offices assigned to the defense of the poor according to a mixed model known as the Advocacy for the Poor (Avvocatura dei poveri).

The statute on the judiciary drawn up in 1859, in fact, provided every Court of Appeal with an office of the Advocacy of the Poor, composed of lawyers and prosecutors paid by the State and included in the career of the judiciary (of which they represented the first step). The office offered advice and procedural defense activities for free to the poor, in both civil and criminal matters; it also provided a lawyer for any accused person who had appointed one of its choice. In all inferior courts, however, these activities were attributed by the judge to one member of the local Bar Association, who performed his tasks free of charge (pro bono).

The admission to the ‘benefit’, as it was called, required the presentation of a poverty certificate issued by the mayor of the city of residence and, in civil cases only, the demonstration of the probable substantiation of the claims that the plaintiff wanted to take to court (fumus boni iuris); it included the exemption from litigation costs, which were possibly recovered from the losing party at the end of the trial.

This model had its roots in the paternalism of medieval Sabaudian rulers, who believed that this way they would fulfill their task as guardians of the weak and the marginalized subjects of their crown. It was an exception, compared to the legal systems of the other pre-unification States, which in large majority confined themselves to entrust the defense of the poor to private lawyers, who were supposed to perform their duties pro bono.

The effort for national unification in terms of war expenditures, as well as the union of the public debts of the pre-unification states and the difficulties in standardizing and rationalizing the tax levy on the whole territory led to a financial emergency that filled the parliamentary debates at least until 1867 and that was addressed with a policy of abrupt intervention on public spending.

Therefore, in this context it is not surprising that some of the criticisms already made to the Advocacy of the poor, mainly linked to the impossibility of the defender’s autonomous choice and to the suspicion that a public defense magistrate was too conniving with the equally prosecutor’s public magistrate, converged with the budgetary requirements in causing the abolition of the public office for the defense of the poor, in favor of a complete pro bono regime.