National Report

Summary of Contents

1. General Information

1.1. Government

Ireland is a sovereign, independent, democratic state which operates a parliamentary democracy. There are three arms of the Irish government; the executive, legislature, and the judiciary.

The executive arm of the Irish government consists of the President (Uachtarán na hÉireann), Prime Minister (Taoiseach) and the deputy head of government (Tánaiste) and Cabinet ministers. The President is the head of state and is elected for a seven-year term with a maximum of two terms[1]. Political power is vested in the Taoiseach who is the head of government. The lower house of the parliament nominates the Taoiseach who is then appointed by the president. The executive is responsible for the daily operation of the country.

The judiciary consists of the District Court, Circuit Court, High Court, Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court. The function of the Supreme Court is to resolve issues pertaining to the interpretation of the constitution while the court of appeal resolves appeals. The other courts resolve matters that affect the citizenry including criminal and civil issues. The constitution, common law, and statutory law are used in the country when administering justice[2].

The legislature of Ireland is known as Oireachtas Éireann. It consists of the president and the two chambers of parliament; Dáil Éireann or Lower House and Seanad Éireann or Senate. The lower house of the parliament nominates the Taoiseach who is then appointed by the president. The function of the legislature is to introduce, amend or remove existing laws.

There are five types of elections in Ireland; local, European, parliamentary, presidential and referendums. The president, members of the Dáil Éireann, European Parliament, and the local government are democratically elected. The members of the Senate are elected, nominated or elected by university constituencies. The Constitution of Ireland can be amended by referendum. A proposal to amend the Constitution of Ireland must first be approved by both Houses of the Oireachtas, submitted to a referendum and signed into law by the President.

1.2. Demography

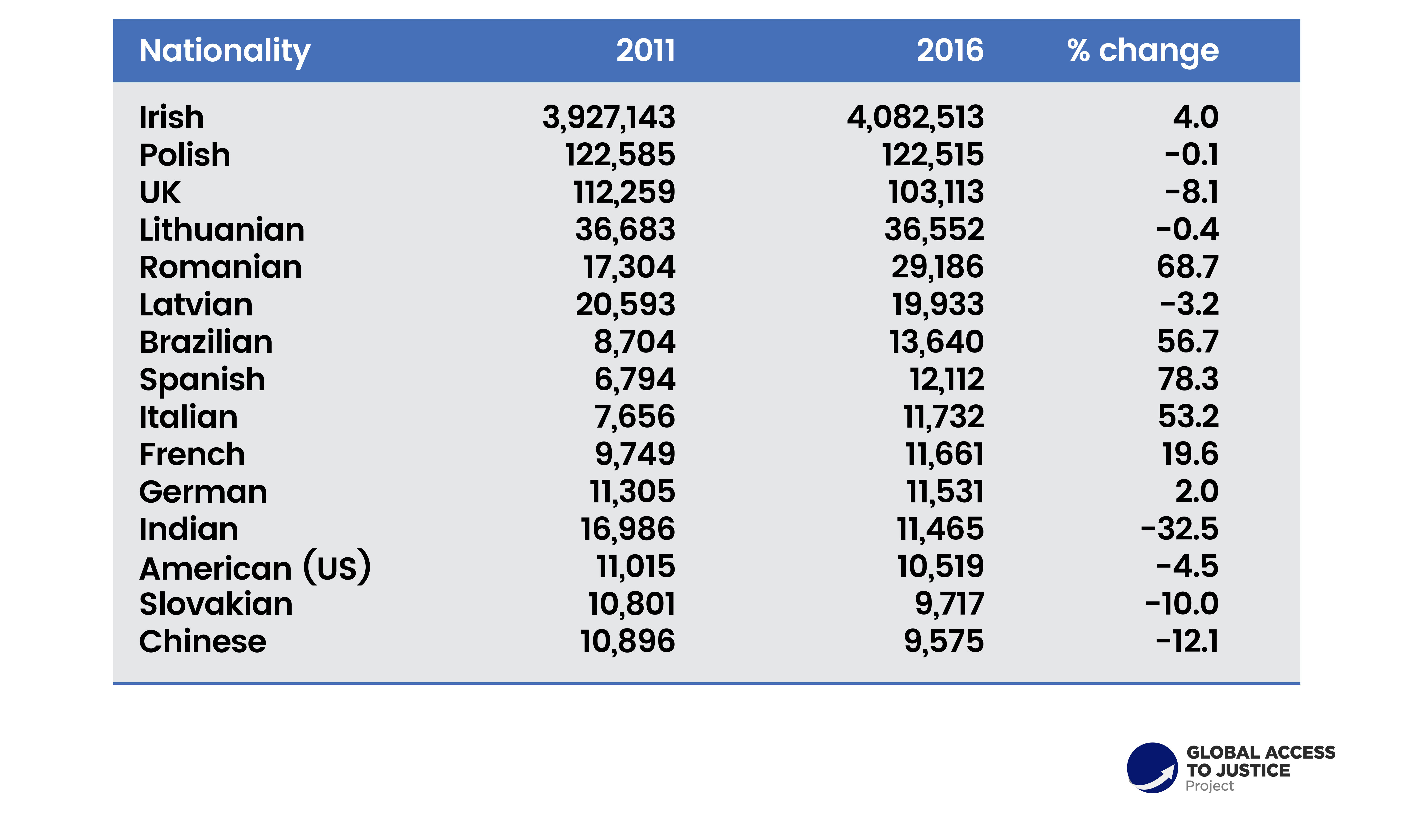

Ireland’s population was 4,761,865 persons in April 2016 an increase of 173,613 persons since the previous Census in April 2011[3]. The number of Irish residents born outside Ireland stood at 810,406 in 2016. In April 2016, persons born abroad accounted for 17.3 per cent of the population, up from 17 per cent in 2011. However, this increase is in sharp contrast to the previous inter-censal period which saw the number born outside Ireland rise by 154,141 over the period 2006 to 2011.

Chart 1. Persons usually resident by nationality for selected countries, 2011-2016[4]

Source: CSO (2017) Population change and historical perspective

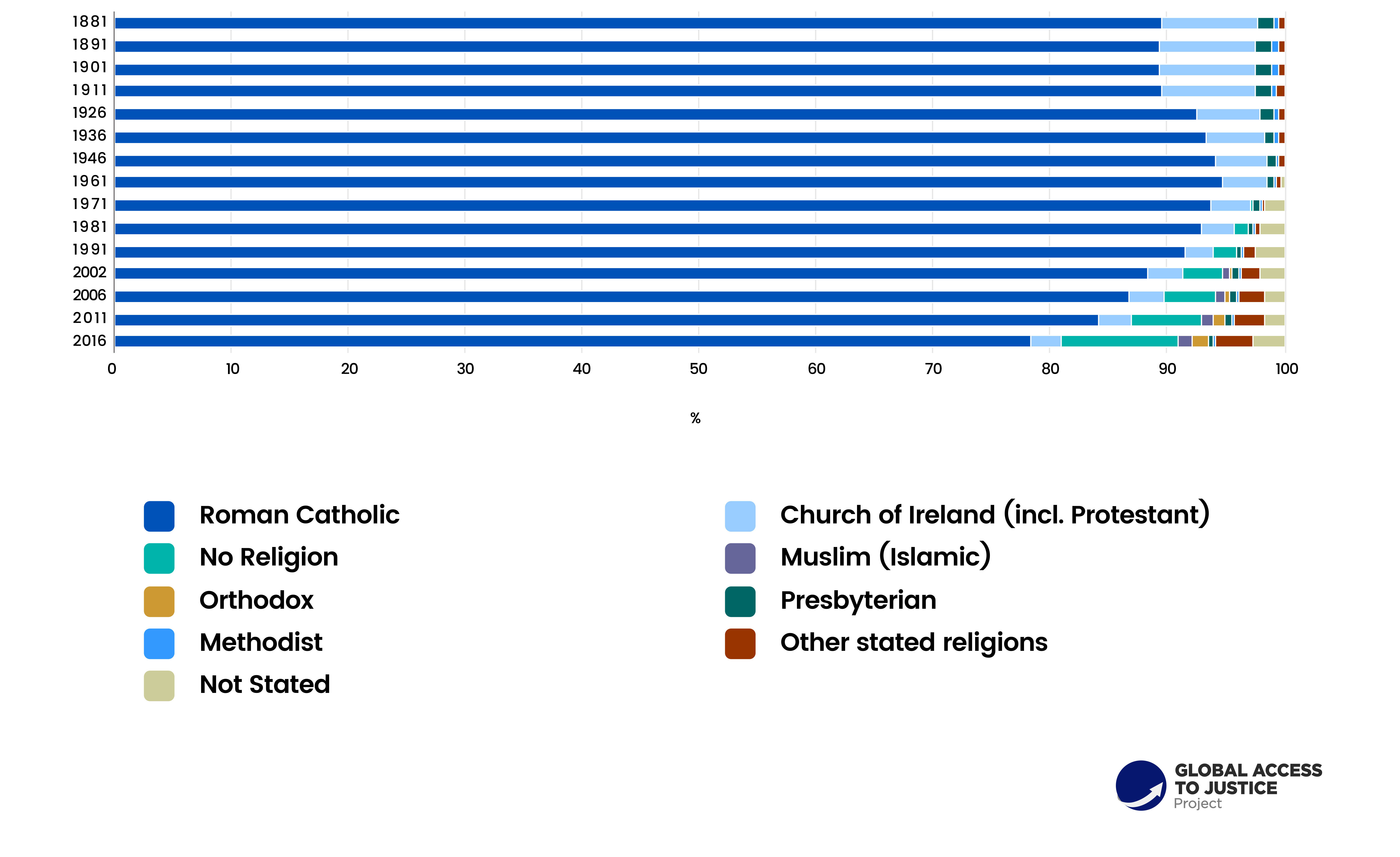

In 2016, Roman Catholics accounted for 78.3 per cent of the population compared with 84.2 per cent in 2011. Historical census results show that Roman Catholics represented on average 89.5 per cent of the population in each of the four censuses held from 1881 to 1911[5]. It subsequently rose to a peak in 1961 of 94.9 per cent. Since then, its proportion of the total population has slowly declined as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2. Percentage distribution of religious populations, 1881-2016

Source: CSO (2017) Census of Population 2016 – Profile 8 Irish Travellers, Ethnicity and Religion.

1.3. Economy

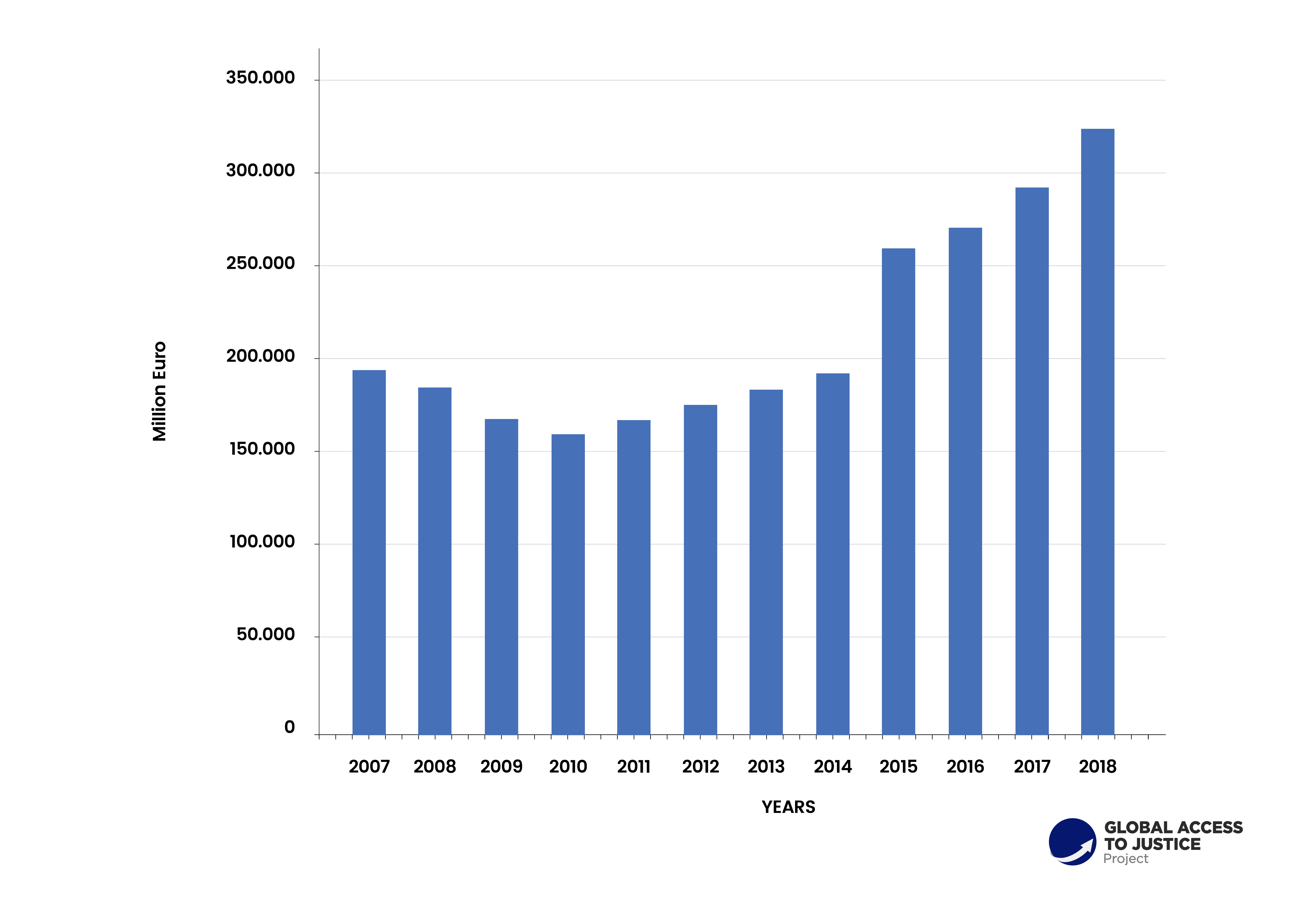

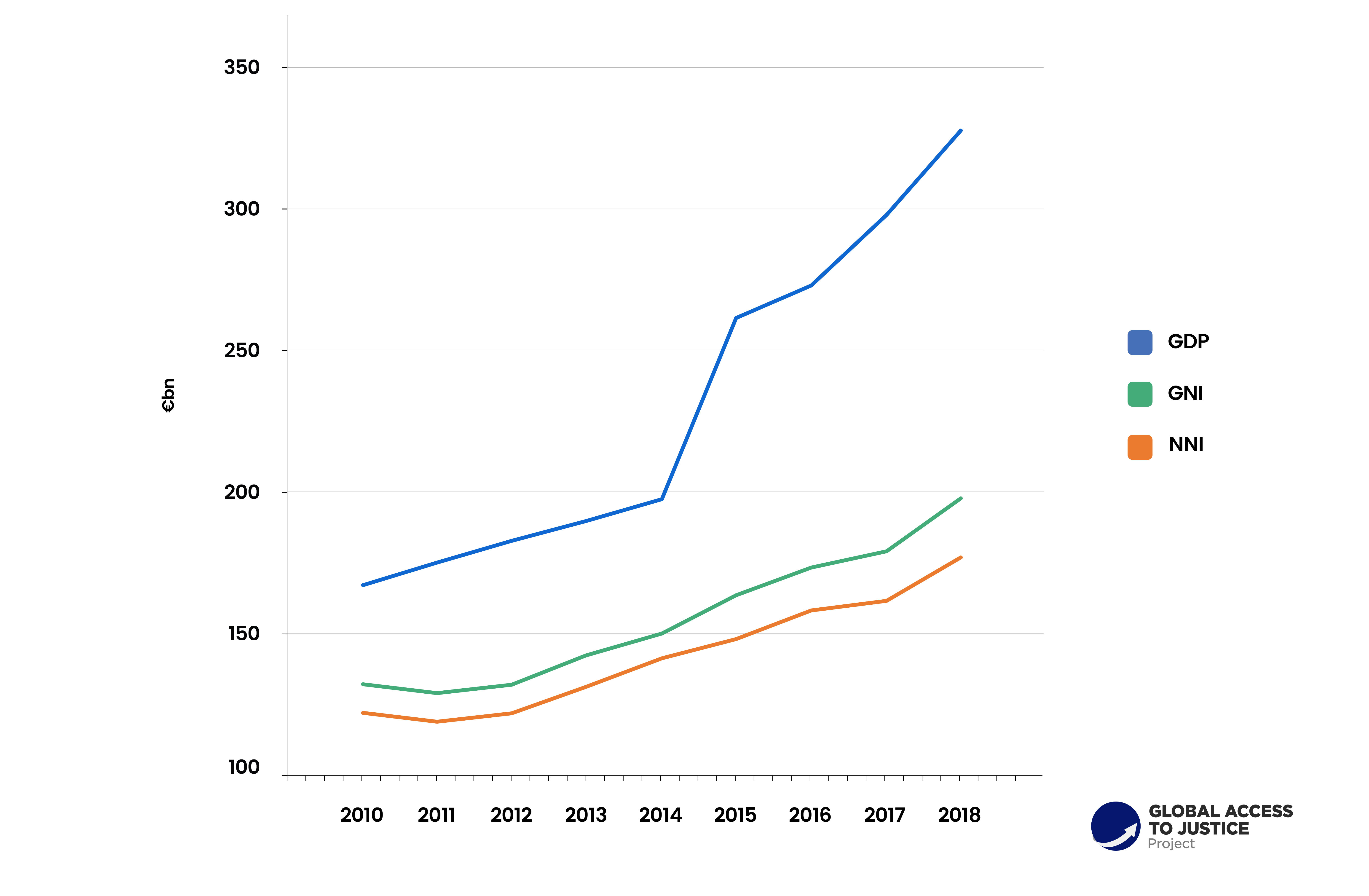

Ireland’s economy is primarily a knowledge based economy focused on financial services, high-tech, pharmaceuticals, life sciences and agri-business. Ireland is ranked 6th on the Index of Economic Freedom[6] as an open economy with a significant reliance on high-value foreign direct investment. While Ireland experienced continuous growth from the mid 1990’s until 2007, the 2008 financial crisis led to a recession that severely affected the economy. Chart 3 shows the changes in Gross Domestic Product over the last decade in Ireland[7]. Ireland ranks as the second highest country in the OECD based on GDP per capita[8].

Chart 3. GDP at market prices (Million Euro)

Chart 4 shows the variance between GDP and Modified GNI[9] in Ireland reflecting the distorting effects of multinational companies operating in Ireland.

Chart 4. Comparison of GDP, Modified GNI and NNI at current prices 2010-2018[10]

Source: CSO (2019) National Income and Expenditure 2018

The 2019 Human Development Index value of 0.942 ranks Ireland as having the third highest quality of life in the world based on three categories: health, education and income. Life expectancy at birth in Ireland is 82.10 years. The expected years of schooling are 18.79 years and mean years of schooling is 12.53 years. Ireland’s purchasing power parity (PPP) is $55,660[11].

2. THE LEGAL SYSTEM

2.1. Background

Ireland was regarded as the “first adventure of the common law” and it was brought by the Normans when they invaded in 1169 and, while initially only applicable in the “Pale” in the east of the country, was gradually extended to the whole country by the seventeenth century. The ancient Irish legal system was known as the Brehon Law and while it survived in areas outside of Anglo-Norman influence until the seventeenth century, it is no longer relevant and no serious consideration was given to re-introducing it after independence. The Lordship, later Kingdom of Ireland established by the Anglo-Normans in Ireland existed as a legal jurisdiction with a separate judiciary and a separate but somewhat limited legislature (particularly during the operation of Poynings Law 1494, which operated to extend certain English and later British laws to Ireland and effectively subordinated the Irish Parliament to the English/British parliament until its effective repeal in 1782) but with an Executive wholly under the control of the English, later British Crown, through the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and (later) his Chief Secretary.

Although the Irish Parliament achieved legislative independence in 1782 this was short-lived and following an unsuccessful rebellion in 1798, the Irish and British Parliaments passed the Act of Union 1800 which unified Ireland and Great Britain into a single state (though Ireland, within the new United Kingdom, remained a separate legal jurisdiction with a separate judiciary). In 1920 the Government of Ireland Act partitioned Ireland into two separate legal jurisdictions within the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, the latter quickly succeeded by the independent Irish Free State (Saorstat Éireann) in 1922.

2.2. Sources of Irish law

In 1937 the Irish Free State adopted a new Constitution of Ireland, which saw the name of the state changed to simply Ireland (though since 1948 often referred to by its statutory description, “the Republic of Ireland”, particularly when distinguishing from Northern Ireland which remains part of the United Kingdom). This Constitution as amended remains in force. Ireland joined the European Communities (now the European Union) in 1973. As a result Irish law, including the Constitution, is now subject to the supremacy of EU law. Because the Constitution (and that of the Irish Free State before it) carried over all laws in force at the time of its promulgation, Irish law also includes Acts of Parliament (including Acts of the various previous parliaments since 1171 that have remained in force), Statutory Instruments (a form of delegated legislation or executive order made by Ministers and other bodies empowered to do so) and the common law as it has developed over the years.

Being a common law system means that the principle of stare decisis (“let the decision stand”) arises – courts are bound to follow the reasoning of previous decisions in relation to similar matters. As an example of the extent of the common law, murder, probably the most serious offence known to the law, remains defined primarily under the common law and no statutory offence has been created to replace it.

2.3. The courts system

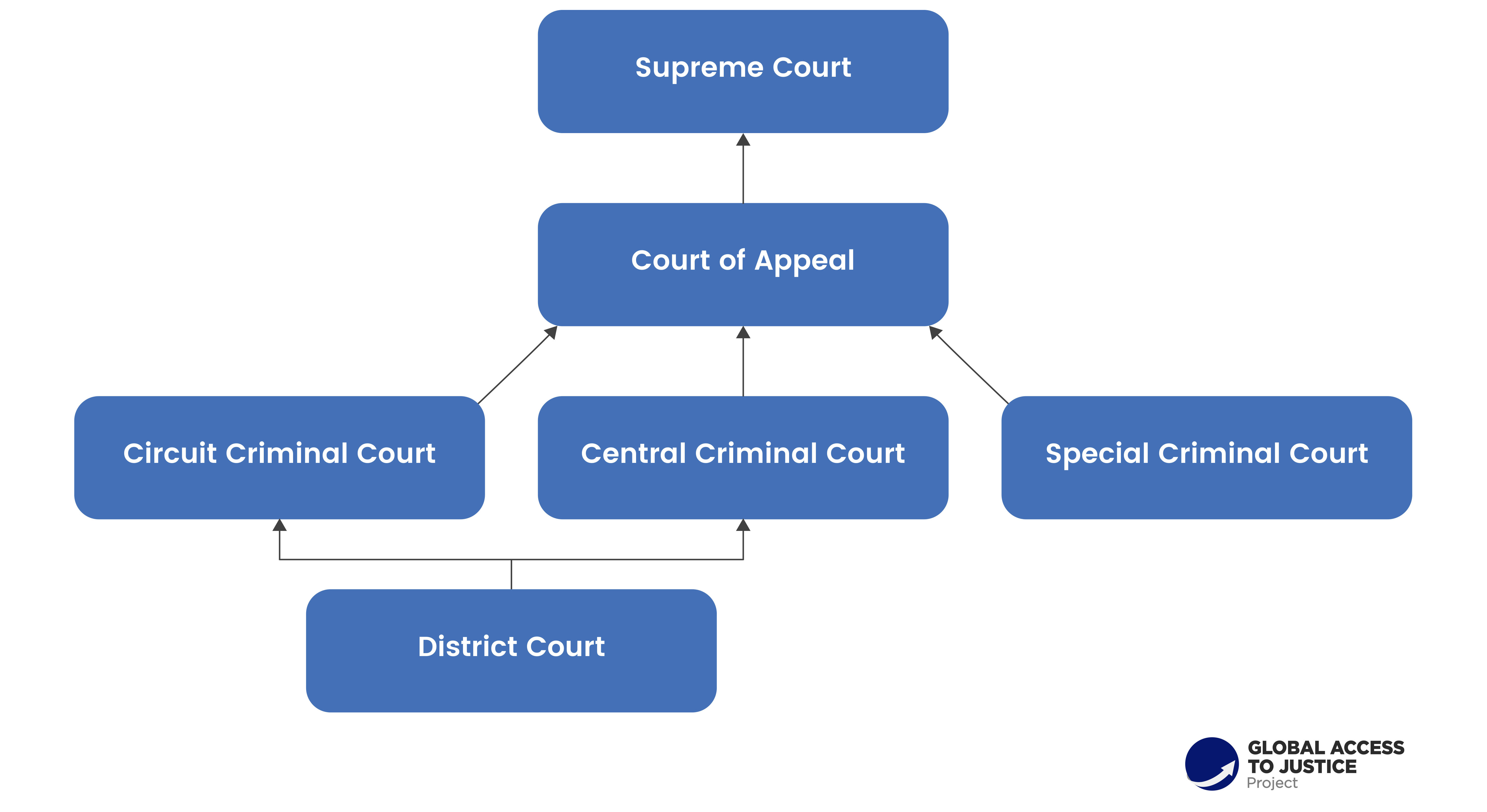

The Courts system as it exists at present was established pursuant to the Constitution under the Courts (Establishment and Constitution) Act 1961 (as amended, among other Acts, by the Court of Appeal Act 2014). The main courts are the District Court, Circuit Court, High Court (Central Criminal Court in criminal trials), Court of Appeal, and Supreme Court, all of which exercise both criminal and civil jurisdiction. The Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, and High Court (collectively the “Superior Courts”) were all established under the Constitution. The Supreme Court is the highest court and the final court of appeal; it has limited original jurisdiction, chiefly in cases where the President has referred a Bill passed by Parliament to it for a ruling as to its constitutionality. The Court of Appeal is an intermediate appeal court that hears appeals from the High Court in civil cases and from trial courts in criminal cases. The High Court is the superior trial court and it can in principle deal with any question of law either civil or criminal. In practice it exercises jurisdiction over civil claims worth more than €75,000 in value as well as judicial review and certain other serious matters. It also hears appeals from the Circuit Court in civil matters. In criminal cases it is called the Central Criminal Court and tries murder, rape, and treason.

The courts of “local and limited jurisdiction”, established solely under statute law, are the Circuit Court and District Court. The Circuit Court, which sits in each county, deals with civil claims between €15,000 – €75,000 and matrimonial cases, and as the Circuit Criminal Court carries out most trials on indictment other than those in the jurisdiction of the Central Criminal Court. It also deals with appeals from the District Court in both civil and criminal matters. The District Court, which sits in venues throughout the country, deals with civil matters below €15,000, most family law matters involving children, and public law child care matters. On the criminal side it tries minor offences summarily (without a jury) and can hand down sentences of up to twelve months. When dealing with offences involving minors it is called the Children’s Court and can try summarily any offence except those dealt with by the Central Criminal Court.

A Special Criminal Court also exists which mainly tries serious terrorist and organised crime cases. It consists of three judges drawn from the High, Circuit, and District Courts sitting without a jury.

Ireland also has a system of administrative tribunals such as the Workplace Relations Commission, Labour Court (despite its name, it is not a court of law), International Protection Appeals Tribunal, Residential Tenancies Board, Adoption Authority etc. These all have specific jurisdiction conferred under specific pieces of legislation with different criteria for membership; Ireland does not generally regard tribunal members as part of the judiciary though some tribunals provide for a sitting judge of a court to be appointed a member.

Chart 5. Court structure. Organisational chart – Civil

Note: in appeals from the District Court to the Circuit Court and the Circuit Court to the High Court, the case cannot generally be appealed any further. There also exists an “appeal by way of case stated” on a point of law only from the District Court to the High Court and from the Circuit Court to the Court of Appeal but for simplicity this is not illustrated above.

Chart 6. Court structure. Organisational chart – Criminal

Chart 7. Number of cases – Civil[1]

| Incoming | Resolved | |||

| 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | |

| District Court | 137,493 | 133,823 | 106,698 | 121,075 |

| Circuit Court | 49,253 | 53,795 | 39,606 | 36,612 |

| High Court | 39,219 | 39,659 | 30,982 | 27,398 |

| Court of Appeal | 499 | 611 | 475 | 470 |

| Supreme Court | 308 | 234 | 285 | 275 |

| Total | 226,772 | 228,122 | 178,046 | 185,830 |

Chart 8. Number of cases – Criminal[2]

| Incoming | Resolved | |||

| 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | |

| District Court | 391,296 | 391,207 | 296,971 | 290,567 |

| Circuit Criminal Court | 33,096 | 32,787 | 60,556 | 47,716 |

| Special Criminal Court | 51 | 54 | 74 | 50 |

| Central Criminal Court | 1,202 | 1,761 | 1,941 | 2,098 |

| Court of Appeal | 1,266 | 1,281 | 1,472 | 1,078 |

| Supreme Court | 8 | 11 | 17 | 9 |

| Total | 426,919 | 427,101 | 361,031 | 341,518 |

2.4. The legal profession

Legal representation is not mandatory in Ireland. Any litigant or defendant in a criminal case is entitled to represent themselves as a “litigant in person” or lay litigant. There are certain restrictions in relation to personal cross-examination of certain witnesses in rape/sexual assault cases and applications for domestic violence orders and provisions for the appointment of a lawyer to conduct cross-examinations in the interests of justice where this occurs.

There are effectively two branches of the legal profession – solicitors and barristers. Solicitors are the by far more numerous, with just under 11,000 holders of practising certificates in 2018, while there are about 2,300 practising barristers (it should be pointed out that in both cases there would be many more persons who are qualified to practice but do not do so, because, for example, they work as an in-house legal advisor). The essential difference between a solicitor and barrister is that a solicitor may always take instructions directly from a client and a barrister in most cases may not (but is instead required to act on foot of a “brief” from a solicitor). A solicitor is also entitled to act in place of their client in transactions (i.e. act as an “attorney”) but a barrister may not. In more practical terms, solicitors tended to offer general advice and represent their clients in commercial transactions (such as conveyancing of a property, the establishment of a company, corporate activity etc) and in the District Court. Barristers on the other hand were specialists at court work, drafting pleadings, offering advices on particular matters (“Counsel’s opinion”) and advocacy in the higher courts. Barristers tended, particularly those in more advanced stages of their careers, to specialise in particular matters whereas many solicitors remain general practitioners.

Solicitors operate as sole practitioners or as part of a law firm with other solicitors (traditionally, all solicitor firms in the country were either sole practitioners or unlimited partnerships though the limited liability partnership was introduced in October 2019). Traditionally only solicitors were allowed to be partners in a law firm. Recent legislation allows for the introduction of multi-disciplinary practices but this is yet to be brought into force.

Barristers in private practice are required to act as sole practitioners and the overwhelming majority are members of a professional body called the Law Library (also known as “The Bar of Ireland”) though it is not an absolute legal requirement to be so. Since the commencement of the Legal Services Regulation Act 2015 in October 2019, the definition of “practising barrister” which was previously almost synonymous with “member of the Law Library” has been widened somewhat. The Legal Services Regulatory Authority regards barristers employed in a legal role as practising barristers which would previously not have been in the case.

2.5. Paralegals

The term “paralegal” in Ireland is not statutorily defined but paralegals are not regarded as lawyers in Ireland. An Irish Institute of Legal Executives exists but membership is by no means universal among those in paralegal roles. It defines a legal executive as “a person qualified by accumulated practical experience and/or academic credentials to offer rather more than secretarial or administrative assistance to a Solicitor or other legal practitioner in the handling of client cases relating to conveyancing, probate, criminal, civil, family or other legal matters”. Representation by paralegals is not generally allowed though they often attend Counsel at courts and tribunals. As there is no statutory definition of the word “paralegal” it is impossible to provide numbers of persons employed in positions that would be roughly regarded as paralegal.

2.6. The judiciary

Ireland has an independent judiciary consisting of the following:

Chart 9. The judiciary

| Position | Number | Qualifications |

| Chief Justice of Ireland | 1 | Practice as a solicitor or barrister for at least twelve years including two years continuous prior to appointment (service as a judge, or Advocate-General of the CJEU, counts as practice). |

| President of the Court of Appeal | 1 | |

| President of the High Court | 1 | |

| Judge of the Supreme Court | 9 | |

| Judge of the Court of Appeal | 15 | |

| Judge of the High Court | 35 | |

| President of the Circuit Court | 1 (+1 former still sitting as a judge) | Practice as a solicitor or barrister for at least ten years including two years continuous prior to appointment, or is already a Circuit Court Judge, a Specialist Judge, or a District Judge. |

| Circuit Court Judge | 37 | |

| Specialist Judge (Circuit Court) | 3 | |

| President of the District Court | 1 | |

| District Judge | 63 |

The Chief Justice, President of the Court of Appeal, and President of the High Court are entitled to sit ex-officio in the Superior Courts other than the one they preside in, while the Presidents of the District and Circuit Courts are each entitled to sit ex-officio in the court above.

Ireland does not have “career judges” and judges are appointed from the experienced ranks of solicitors and barristers. Appointment is by the President on the advice of the Government and upon recommendation by an independent Judicial Appointments Advisory Board (the Government is not obliged to appoint, and does not say whether it has appointed, one of the persons recommended by the Appointments Board). A Judicial Appointments Commission Bill is currently at an advanced stage in Parliament which will reform this system to a degree.

Judges are appointed for life but must retire at age 70. They may be removed by Parliament for “stated misbehavior or incapacity” but this has never happened. The Presidents of each of the Courts are appointed for seven year terms and this is not renewable. Once that term is expired they may continue to sit on the bench and if they do so, they retain their precedence over the ordinary judges of the court and their ex-officio memberships of other courts. Judges of the District and Circuit Court may be transferred between venues (or made movable judges) at the absolute discretion of the president of the court concerned.

Approximately 28% of judges are female. There is no statistical information on race though anecdotally there are very few minority race judicial office holders in Ireland at present.

There are also a number of “quasi judicial office holders” – the Master of the High Court and the Legal Costs Adjudicators (Taxing Masters) who are not regarded as judges in the Irish context, and county registrars in the Circuit Court. While these officials are not judges, they do sit in open Court and if they are barristers (many county registrars are solicitors) they may wear their wigs, gowns, and tabs and if so may appear similar to judges to observers. The Master and county registrars chiefly sit to hear pre-trial applications of a procedural nature, while legal costs adjudicators measure the costs of actions (if they are not agreed between the parties).

There are no part-time judges in Ireland and no lay magistrates. There is a lay office of peace commissioner but they do not nowadays exercise any judicial functions.

2.7. Public prosecutors

The Constitution of Ireland 1937 provided that criminal offences, other than in a court of summary jurisdiction, would be prosecuted “in the name of the People at the suit of the Attorney General or some other person authorised in law for that purpose”. Since the enactment of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1974 the vast majority of offences prosecuted on indictment are done so by or in the name of the Director of Public Prosecutions, who is appointed by the Government but independent in the performance of their functions. (Previously, this role was carried out by the Attorney General, the chief law officer of the Government who is a political appointee who serves at the Prime Minister’s pleasure).

Ireland has no nationwide public prosecution service; while lawyers employed by the DPP conduct prosecutions in the Dublin courts; outside of Dublin local lawyers (called State Solicitors) in private practice conduct prosecutions. Police officers prosecute (in the name of the DPP) most summary offences in the District Court. There are specific instances where certain offences (mainly of a regulatory nature) can be summarily prosecuted by appropriate regulatory bodies.

There are 202 staff employed in the Office of the DPP, but this includes non-lawyer members of staff. As with all civil service positions in Ireland recruitment is by open competition. There are 32 state solicitors outside Dublin appointed on a contract of up to ten years. However this is not the full extent of all lawyers involved in prosecution as the DPP maintains panels of barristers who act for the prosecution on its behalf.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

The police (the Garda Síochána) are responsible for a criminal investigation. A person may be arrested by the police under warrant however the vast majority of arrests are without warrant. Any person (who need not necessarily be a police officer) may arrest any person who has committed, or is committing a breach of the peace or whom they reasonably believe is going to commit a breach of the peace.

An arrest may be carried out without warrant where statutorily provided for. In particular, Irish law provides for the concept of an “arrestable offence” which is an offence which can be punished by imprisonment for five years or more. Any person may arrest without warrant a person whom he or she with reasonable cause, suspects to be in the act of committing an arrestable offence. Where an arrestable offence has been committed any person can arrest without warrant anyone whom he or she with reasonable cause, suspects to be guilty of the offence. Where a member of the police with reasonable cause suspects that an arrestable offence has been committed he or she may arrest without warrant anyone whom with reasonable cause, he or she suspects to be guilty of the offence.

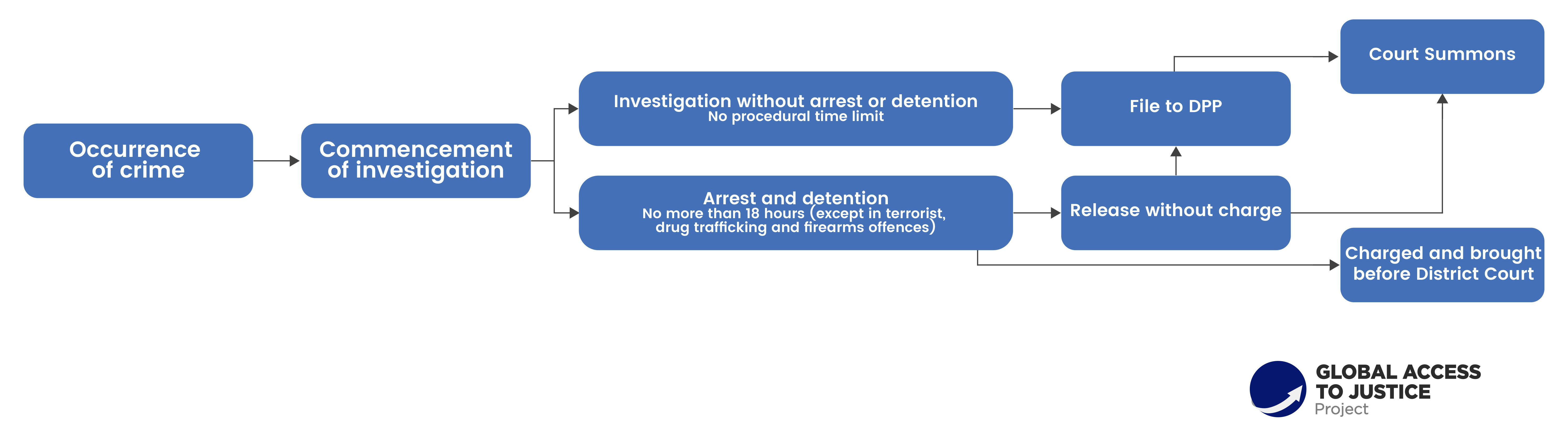

There are maximum periods applicable to persons brought to a police station but these differ based on the offence. However, for most arrestable offences, the normal maximum is six hours from time of arrest, a further six hours where directed by an officer not below the rank of Superintendent, and a further six hours where directed by an officer not below the rank of Chief Superintendent. The test for detention is that the officer concerned has reasonable grounds to believe that such detention is necessary for the proper investigation of the offence. However in terrorist, drug trafficking, and firearms offences, the maximum periods are longer – six hours from time arrest, a further eighteen hours where directed by an officer not below the rank of Superintendent, a further 24 hours where directed by an officer not below the rank of Chief Superintendent, a further 72 hours where authorised by a warrant obtained from a judge, which can be extended on a further warrant for a further 48 hours. Where a person is brought before a court during this time, the period is extended for the duration of the court sitting.

There is no legal time limit for completing a police investigation, however for summary offences (that is, offences which will be heard before a District Judge sitting alone) the prosecution must commence within six months of the alleged offence. There is no statute of limitations for indictable offences, that is, those offences which may have a jury trial. Most indictable offences (with the exception of murder, rape, and treason) may be dealt with summarily and this is explained later.

Chart 10. Police investigation phase

Criminal proceedings can be generally instituted in three ways (only two of which are generally used). Where a person has been arrested the “charge sheet procedure” can be used (where the offences are set out on a charge sheet, with a copy furnished to the defendant and the original lodged with the court office). The second method, used where a person has not been arrested or was released without charge, is for a summons to be issued by the court office on the application of a police officer. The third form, which is used in the very rare instance of a private prosecution (i.e. prosecution taken by a private citizen and not by a public authority), is for an “information” to be laid before a District Judge containing details of the alleged offence. This very rare form of proceeding is the only way a victim can institute and be a party to criminal proceedings. However, for reasons which shall become apparent later, such prosecutions can only be practically undertaken for summary offences.

There is no requirement that a person be legally represented in any legal proceedings but legal aid is available pursuant to the provisions of the Criminal Justice (Legal Aid) Act 1962. It is open to any defendant to conduct their own defence in person (subject to certain restrictions which apply to cross-examination of certain witnesses in certain rape and sexual assault cases).

All criminal prosecutions begin in the local District Court (except in certain terrorist and organised crime cases which can be instituted in the Special Criminal Court). At the first appearance the police officer will give evidence of arrest, charge, and caution. An application for legal aid may be made at this point. While a summary offence may be tried there and then, this will normally not occur and there will normally be an adjournment or the defendant will be remanded in custody or, where the court decides, on bail (the latter normally subject to an appropriate sum of money being paid as a recognisance and, in some cases, the appointment of a “surety” or guarantor).

As noted above, offences in Ireland fall into three general categories – summary offences, indictable offences and “either way” offences that can be tried either summarily or on indictment (the latter also effectively has two subcategories, those which carry a right of election to a trial on indictment and those that do not). In the case of either-way offences the DPP will give “directions” as to the manner of trial. Where the DPP consents to summary disposal the District Judge must accept jurisdiction in order for a summary trial to proceed. Where the defendant has the right to elect for a trial on indictment they may do so – if they do not, or there is no right of election the matter will be tried summarily as long as the DPP has directed and the District Judge has accepted jurisdiction. Note that the defendant has no right in either case to elect for a summary trial. In the case of a child almost all offences (other than murder, manslaughter and treason) can be summarily tried in the District Court which sits as the Children’s Court for this purpose.

There is no longer any “preliminary examination” by a District Judge in the Irish system and where the DPP directs trial on indictment the court must send the case forward to the trial court (which depending on the offence will either be the local Circuit Criminal Court or the Central Criminal Court, which almost always sits exclusively in Dublin). However sending forward will not occur until the prosecution has prepared and served a “Book of Evidence” which contains copies of all the evidence which the prosecution will rely on at the trial.

Certain terrorist and organised crime offences are tried on indictment by a non-jury court called the Special Criminal Court. This court sits with a bench of three usually consisting of a High Court judge, a Circuit Court Judge, and a District Court Judge. Of note is that such proceedings may be instituted in the Special Criminal Court rather than in the District Court as is usually the case.

3.1.1. Summary trial

For summary offences, the defendant will usually apply for a summary of the evidence and a copy of witness statements given to the police. Once ready for trial the procedure is that the prosecutor (usually a police officer) will call their witnesses and these may be cross-examined by the defence. The defence may then make an application that there is “no case to answer” (if they feel the prosecution has failed to prove the facts of the offence) but if that application is refused the defence may go into evidence and defence witnesses may be cross-examined by the prosecutor. There will be a closing submission on behalf of the prosecution and by the defence. The judge may give a verdict (to convict or acquit) there and then or he/she may adjourn the case and give their verdict on a later date. Where the defendant is acquitted the proceedings are at an end. Where the defendant is convicted the matter will proceed to sentencing. The Court will hear evidence regarding any previous convictions and a “plea in mitigation” on behalf of the defendant. The District Court can impose a maximum sentence of twelve months imprisonment (though, if the offence is “either-way”, and the defendant pleads guilty, then the District Judge can send forward the matter to the Circuit Criminal Court for sentencing only). After sentencing there is the possibility of an appeal to the Circuit Court.

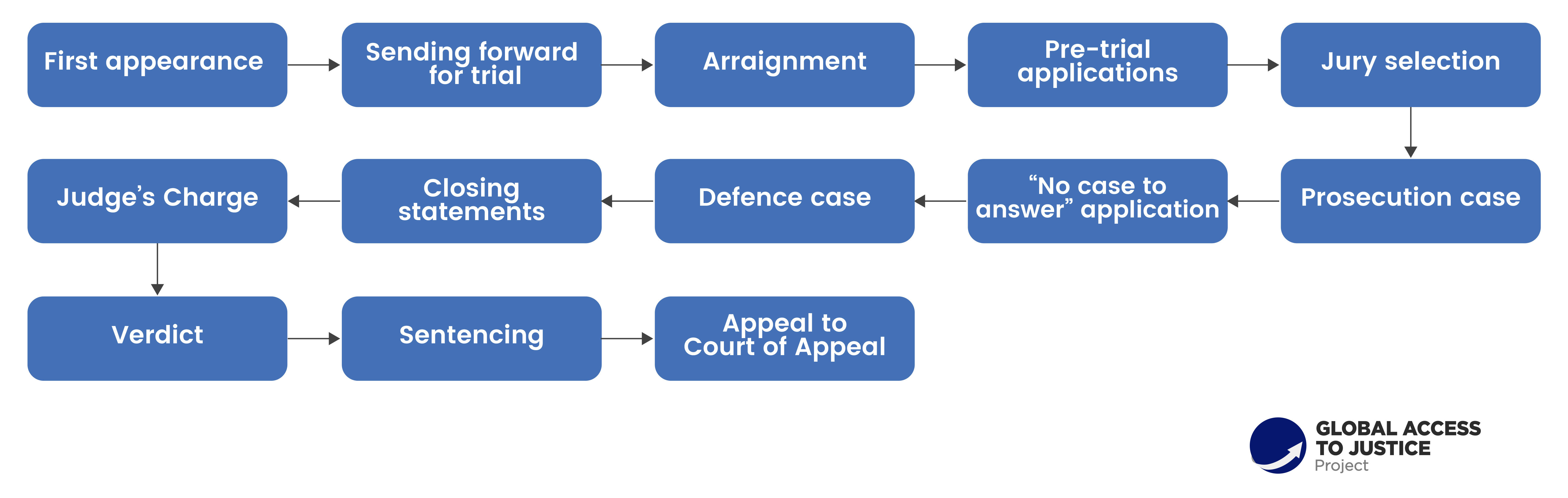

3.1.2. Trial on indictment

Following sending forward for trial the first stage is arraignment. The indictment will be read to the accused and he will be asked whether he pleads guilty or not guilty (there is also the rare possibility that the accused will plead autrefois i.e. that he has already been tried and/or convicted of the offence of which he is charged). There may be pre-trial applications made in relation to various matters one of which may be an application to the judge to dismiss one or more of the charges on the basis that there is insufficient evidence to place the accused on trial.

Prior to the beginning of the trial a jury will be selected and empanelled (it is open to the prosecution and defence to challenge seven potential jurors without cause and any number with cause). The accused will then be arraigned before the jury and asked to enter a plea.

The trial begins with the prosecution’s opening statement following which each prosecution witness will be called, examined in chief by prosecuting counsel, cross-examined by defence counsel (if the defence wishes to do so) and re-examined by prosecuting counsel (only if cross-examination has occurred and the prosecution wishes to do so). At the close of the prosecution case an application may be made by the defence of “no case to answer”; that is to say that the evidence which has been put forward by the prosecution is insufficient to convict the accused. If this is not made or it is unsuccessful the defence begins. The defence do not generally make an opening statement but it can be made in complex cases. The defence witnesses, if any, are then called (with the accused, if he intends to give evidence, being called first – there is no requirement that the accused give evidence in his own case) and are examined, cross-examined, and re-examined in similar fashion to the prosecution case.

Following the completion of the defence case the prosecution and the defence will make their closing statement. The judge will then charge the jury (which will involve summing up the evidence and direct the jury to the law relevant to the offence) and the jury will then retire to consider their verdict.

If the accused is acquitted, the proceedings are concluded. If they are convicted the accused will be remanded in custody or on bail for sentencing at a later date. There is the possibility of an appeal to the Court of Appeal by the defence. The prosecution may appeal the sentence (on the grounds that it is “unduly lenient”) but not the verdict.

There is no time limit for the completion of criminal proceedings.

Chart 11. Process map

3.2. Civil Procedure

In Ireland civil cases may be commenced in one of three first instance courts – generally speaking, the District Court deals with claims with a monetary value of less than €15,000, the Circuit Court with claims of a monetary value of between €15,000 – €75,000, and the High Court with all other claims. (Strictly according to the Constitution, any claim may be commenced in the High Court, but a successful plaintiff who does so when they could have instituted their claim in a lower court will be penalised by having their costs limited at the amount the lower court could have awarded. In practice, it is unknown for a plaintiff to take a claim in the High Court which could have been commenced in a lower court.

Ireland does not have a unified set of civil procedure rules and different rules are applicable in each of the three first instance courts. It should be noted, in particular, that the rules pertaining in the District Court (which were heavily revised in 2014) are very different to those pertaining in the other Courts, to the point where the terminology used is different to an extent. The remainder of this topic will describe the procedure in the High Court and Circuit Court primarily.

3.2.1. Pre-litigation and ADR

Prior to commencing litigation a Plaintiff (the person who takes the claim) is normally required to write a pre-litigation letter to the Defendant (the person against whom the claim is taken). This is not strictly required by the rules but a Plaintiff may be penalised in costs if they do not do so particularly if the matter settles in favour of the Plaintiff at an early stage.

There is no obligation on any party to engage in ADR at any time though solicitors are required to advise clients prior to instituting proceedings about the availability and benefits of mediation and to complete a statutory declaration that they have done so. A court may on the application of a party or of its own motion invite the parties to engage in mediation and adjourn the proceedings to allow them to do so. It is possible for a court to penalise a party in costs if they have been invited to engage in mediation and if they have unreasonably failed to consider doing so or actually done so.

3.2.2. Commencement of proceedings and exchange of pleadings

Litigation is generally commenced in the High Court by the issuing of an originating summons or in some cases by originating notice of motion. The summons informs the Defendant that a Plaintiff has a claim against him and what it is for in general terms. There are four different types of summons but the most common is the plenary summons which is used to start most plenary High Court proceedings other than personal injuries proceedings. It will be followed by a separate Statement of Claim which sets out in detail the particulars of the Plaintiff’s claim and the reliefs claimed. In the Circuit Court, a Civil Bill is the originating document, and is effectively both the summons and the claim. In either case the Defendant acknowledges the proceedings firstly by entering an Appearance with the Court Office, which is a document which indicates their intention to defend the proceedings, and then by delivering a Defence to the Plaintiff, which sets out the nature of their defence (in particular, which parts of the Plaintiff’s claim are admitted and which parts are denied). A Defence may also include a Counterclaim on behalf of the Defendant against the Plaintiff arising out of the same facts. In the Circuit Court the Civil Bill and the Defence (and Counterclaim) are the only pleadings though in the High Court there may be a reply by the Plaintiff and possibly a rejoinder by the Defendant. After this the pleadings are closed though there is a process whereby the contents of the pleadings may be clarified (called seeking “further and better particulars”).

Where the Defendant does not enter an Appearance or deliver a Defence it is possible for the Plaintiff to claim “Judgement in Default” which means that the Court will find for the Plaintiff without the matter being tried. In reality, this seldom occurs in plenary proceedings and the judgement in default process is more frequently used as a means to compel the Defendant to enter an Appearance or deliver a Defence. (In the summary summons procedure, which is discussed later, it is possible to obtain “judgement in the Central Office” without any court hearing in an unanswered case if the papers are in order and this may happen more frequently). Less frequent may be an application by the Defendant for “dismissal for want of prosecution” if the Plaintiff does not progress his claim.

3.2.3. Interlocutory/interim applications including Discovery

Once the pleadings are settled there may be various types of interlocutory/interim applications made including applications for injunctions, freezing orders, search orders etc. Some interlocutory/interim type applications are dealt with by the Master of the High Court or a county registrar in the Circuit Court but in both cases their jurisdiction is limited purely to procedural law and not matters of substantive law.

One of the most important interlocutory applications is the discovery process. This is the process for obtaining a list of documents in the possession or control of another party. It is invariably followed by an application for inspection (that is to actually see the documents which have been listed). Normally a letter seeking voluntary discovery is sent which will be followed by an application to the Court. There is a test of relevance and necessity.

3.2.4. Case management

There is no active judicial case management save where particularly provided for in the Rules. One particular instance where case management by the judiciary does occur is in cases in the Commercial List of the High Court. This is to ensure cases in that list are heard with due expedition.

3.2.5. Trial

Once the matter is ready, and if it has not already been settled the matter will be set down for trial. All civil actions in the Circuit Court and nearly all actions in the High Court are heard by a single judge sitting alone. In a small minority of High Court actions a jury may be present (for example in defamation claims). In even rarer cases a Divisional Court (that is the High Court sitting with more than one judge, usually three judges) may sit but this mainly occurs in cases of exceptional public importance. The judge is the arbiter of all matters of law and fact except where there is a jury – if so, then the jury is the arbiter of all matters of fact and the judge is the arbiter of all matters of law. Ireland is a common law system and the judge therefore takes a largely passive role and does not generally pursue evidence on his/her own account, though he/she may from time to time ask additional questions of witnesses who have been called by the parties.

Unless there is a pre trial application for a determination of a preliminary issue the trial will open with the Plaintiff’s case in which his Counsel will make an opening speech followed by the calling of each of the Plaintiff’s witnesses in turn who will be examined in chief by counsel for the Plaintiff, cross-examined, if the Defendant wishes to do so, by counsel for the Defendant and then re-examined (only if cross-examination took place) by the Plaintiff. Afterwards Counsel for the Defendant may make an opening speech (but this is unusual) and then each of the Defendant’s witnesses will be called and examined in chief, cross-examined, and re-examined in turn. The Plaintiff’s counsel may make a closing speech and if they do the Defendant’s counsel is also entitled to make one. Judgement may follow immediately (though in the High Court in particular, it may be “reserved” to a different date, particularly if the judge has decided to give a written judgement). There is the possibility of an appeal from the Circuit Court to the High Court (which is a de novo appeal, that is to say a full rehearing of the case) or from the High Court to the Court of Appeal (on particular grounds). In the latter case there is the possibility of a further appeal to the Supreme Court or sometimes a “leap frog” appeal, directly from the High Court to the Supreme Court, in cases of exceptional circumstances.

3.2.6. Enforcement

An order will be drawn up later in the terms of the judgement which can then be enforced. A usual perquisite to enforcement is to obtain an order of fiere facias which sends the sheriff/county registrar of the county to seize the debtors assets to satisfy the judgement. This is rarely successful (as the sheriff cannot seize “necessities of life”, items required for the debtor’s business and must be sure the debtor actually owns the goods concerned). The writ will therefore normally be marked nulla bona which means that it failed to satisfy the judgement.

Options open to enforce a judgement are:

- A garnishee order, which orders a third party who owes money to the debtor to pay money to the creditor instead (this is normally the debtor’s employer and the money concerned is part of the debtor’s salary). A statutory version of this is found in family law where it is called an “attachment of earnings order”.

- A judgement mortgage, which converts the debt into a mortgage over the person’s real property

- The appointment of a receiver over the debtor’s property

- Attachment and committal to prison (for contempt of court)

Chart 12. Process map

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

Dispute resolution methods outside the court process are continuing to develop and evolve in Ireland. There are a number of ADR methods available to clients in Ireland.

3.3.1. Mediation

The Legal Aid Board was given responsibility for the State funded family mediation services in 2011. Mediation is a free service to help couples in Ireland who have decided to separate or divorce, or who have already separated, to negotiate their own terms of agreement, while addressing the needs and interests of all involved[1]. The Family Mediation Service encourages the separating couple to co-operate with each other in working out mutually acceptable arrangements on all or any of the following:

- Parenting the children

- Financial support

- Family home and property

- Other problems related to the separation

The Mediation Act 2017 (the Act) came into force on 1st January 2018. The Act provides a statutory framework to promote the resolution of disputes through mediation as an alternative to court proceedings. The underlying objective of the Act is to promote mediation as a viable, effective and efficient alternative to court proceedings, thereby reducing legal costs, speeding up the resolution of disputes and reducing the disadvantages of court proceedings. The Act:

- introduces an obligation on solicitors and barristers to advise parties to consider using mediation as a means of resolving disputes;

- provides that a court may, on its own initiative or on the initiative of any party invite the parties to consider mediation as a means of resolving the dispute;

- provides for an agreed “stopping of the clock” for the purposes of the Statute of Limitations where parties have entered into an agreement to mediate;

- contains general principles for the conduct of mediation by qualified mediators;

- provides that communications between parties during mediation shall be confidential;

- provides for the possible future establishment of a Mediation Council to oversee development of the sector;

- provides for the introduction of codes of practice for the conduct of mediation by qualified mediators.

3.3.2. Voluntary Nature of Mediation

Solicitors have an obligation to inform clients about family mediation as a pre-requisite to the issuing of many standard court proceedings (or the filing of a defence to such proceedings). Solicitors must also give clients information about mediation services available in the State and the possible advantages for the client and the other parties of resolving their dispute other than by court action. However, mediation itself, is defined in the Mediation Act as “a confidential, facilitative and voluntary process in which parties to a dispute, with the assistance of a mediator, attempt to reach a mutually acceptable agreement to resolve the dispute”. Because mediation is voluntary, a person cannot be required to use mediation to resolve their dispute. All of the parties must agree to use mediation to try to resolve the dispute and only the parties decide if, when and how to resolve their dispute through mediation.

3.3.3. The Mediation Process

For an appointment with the Family Mediation Service, both parties must contact the mediation service separately to book themselves in and confirm their willingness to attend. Mediation usually takes between 3 and 6 sessions. Each session lasts approximately one hour. A professionally trained mediator assists the couple to reach their own agreement through confidential discussions where the mediator does not take sides. The mediator may make suggestions about how a dispute may be resolved only when requested to do so by all parties[2]. Successful mediations end with a verbal or written agreement outlining all the details of the couple’s agreement. Although this is not a legal agreement, it can be brought to a solicitor to be drawn into a legal contract or deed of separation or as the basis for a decree of divorce.

3.3.4. Arbitration

Arbitration is one of the oldest forms of Alternative Dispute Resolution and its use in Ireland has been traced back to the Brehon Laws. Arbitration is appropriate in almost all circumstances where litigation before the courts is considered appropriate. It is availed of extensively in relation to international commercial disputes and in respect of both domestic and international disputes arising in the construction and other industries.

It is a process whereby parties agree to refer disputes between them for resolution to an independent third party known as the Arbitrator. The Arbitrator is either agreed by the parties or appointed by an Institution agreed by the parties for the purpose. The mechanism is usually set out in an arbitration clause in a commercial agreement. The Arbitrator works to rules agreed between the parties or, if no such rules are agreed, as laid down by the Arbitration Acts. The Arbitrator is usually an expert in the subject matter of the dispute. Arbitration is similar to court litigation in that it usually involves pleadings and a full hearing based on the law of evidence applicable to Court proceedings.

Arbitration in Ireland is governed by the Arbitration Act 2010. Arbitration relies on the agreement of the parties involved. The parties involved typically agree to submit their disputes to arbitration through an arbitration clause incorporated into the contract between the parties. Occasionally, where a dispute arises and there is no arbitration clause incorporated into the contract, the parties can still agree to submit the dispute to arbitration through a ‘submission agreement’.

Arbitration tends to be somewhat quicker than court proceedings but a substantial arbitration may take approximately one year from beginning to end. This allows for full pleadings, disclosure of documents, witness statements, evidence etc. A simple arbitration, or one that is capable of being conducted on the basis of documents only, should be far more expeditious. Arbitration costs roughly the same as litigation before the Courts. There can be savings in some elements but they are offset by the fact that the parties have to pay for the arbitrator and the venue but not for the judge or the Court.

An arbitrator has the same powers as a judge to award costs against an unsuccessful party. A party may however apply to set aside an arbitrators award in certain circumstances. This rarely occurs. If an application is made to set aside the arbitrators award, and that application is refused by the High Court, there is no appeal against that decision to the Court of Appeal.

3.3.5. Adjudication

The Irish government introduced statutory adjudication in relation to payment disputes under construction contracts through the enactment of the Construction Contracts Act 2013 (the “Act”). The Act applies to all contracts to which the legislation relates entered into after the 25th July 2016. While statutory adjudication only relates to construction contracts, it is possible to extend adjudication into other sectors by contract, or by agreement between the parties in dispute.

An independent third party is paid by those in dispute to consider the contractual issues involved and gives a decision which is temporarily binding in a similar process to Arbitration but without the difficulty associated with finality[3].

3.3.6. Conciliation

Conciliation is a process similar to mediation whereby the conciliator seeks to facilitate a settlement between the parties. In Ireland conciliation is rarely availed of except in respect of construction industry disputes. Under the industry defined procedures for conciliation, the conciliator is obliged to issue a recommendation for the resolution of the dispute if the parties fail to reach settlement.

Conciliation usually arises out of a clause in a construction contract whereby the parties agree to attempt to resolve their dispute through conciliation. The clause provides for the conciliator being appointed by the agreement of the parties or by a specific institution. The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland and Engineers Ireland publish conciliation procedures, one of which will generally apply. The conciliator will attempt to facilitate a settlement between the parties. If this cannot be achieved they will publish a recommendation setting out the basis on which they believe the dispute should be resolved[4].

3.3.7. Expert Determination

Expert determination is a private and confidential method of dispute resolution whereby disputing parties appoint an expert to determine a matter of fact, valuation or law, in a final and binding manner. Where an expert’s decision is not binding but advisory, then this process is known as “Expert Evaluation”[5]. There are five steps to the process: Appointment, Preliminary meeting, Written submissions, Investigation, Determination.

Expert determination is ideally suited to disputes in matters of valuation such as insurance wording disputes, sale of goods disputes, fitness for purpose and boundary disputes. Expert determination can also be used where there is no dispute but a difference which needs to be resolved, for example the valuation of a private business.

3.3.8. Collaborative Law Practice

The aim of collaborative practice is to find a sustainable solution for people who are in family disputes. The essence of the process is that it is in the best interest of the participants to try to resolve the disputes in a non-confrontational way. It is an approach that aims to address the needs of the whole family and bring about resolution through the participation of both parties and their collaborative solicitors, meeting together and resolving all issues by structured discussion. Resolution is based on a commitment to the open sharing of all relevant information and a joint common aim to achieve outcomes through discussion and without the costs, delay, and additional trauma of court litigation. The couple and their collaborative solicitors control the content and timing of the process, and the couple decide upon and agree the outcomes. It is intended that by facing the facts of the separation or divorce in an open, cooperative manner, each participant will seek to achieve lasting solutions that reflect the needs of all involved. However, if either of the participants decides to discontinue the process, then the process ends and both collaborative solicitors must withdraw. If either of the parties decides that they wish to go to court, then neither of the collaborative solicitors involved in the collaborative process can become involved[6].

Collaborative practice is practised in Ireland primarily in the area of family law though the extent to which it is practiced is unclear and, while there was significant impetus 10 to 15 years ago to make it a meaningful dispute resolution option arguably it did not get sufficient traction to make it a mainstream option.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

Article 40.1 of Bunreacht Na hÉireann (the Constitution of Ireland) states:

“All citizens shall, as human persons, be held equal before the law.”

The information in 5.1 of this report also has relevance here whereby it outlines the historical development of the civil and criminal legal aid legislation to ensure equal access to representation and fair trial before the Courts.

4.1. Responsibility for access to justice policy

The Minister for Justice and Equality has responsibility for access to justice policy at Government level.

4.2. Public and scholarly debate around access to justice

There is an iterative debate around access to justice policy in Ireland at the time of writing. By way of example three specific examples are listed below:

- In May 2019, Free Legal Advice Centres (FLAC), an Irish NGO, held its annual conference with the theme of “Access to Justice” in which stakeholders from across the legal landscape – practicing and academic – gave presentations on the theme.

- In October 2019 the Oireachtas (the Irish houses of parliament) Joint Committee on Justice and Equality published its report on reform of the Family Law System. This report contained 38 recommendations, many of which fall under a wider consideration of access to justice issues in the area of family law.

- In November 2019 representatives of the Board were invited to appear before the Oireachtas (the Irish houses of parliament) Joint Committee on Justice and Equality. This invitation was extended to the Bar Council of Ireland, the Law Society of Ireland and a number of other stakeholders for the purpose of making presentations, and contributing to a debate on, access to justice and legal costs.

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid

5.1.1. Civil legal aid

Ireland has had a state-funded civil legal aid scheme since 1979 when the Scheme of Civil Legal Aid and Advice was introduced by the then Minister for Justice. The Scheme was placed on a statutory footing with the enactment of the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995. That Act describes the purpose of the scheme as one to “make provision for the grant by the state of legal aid and advice to persons of insufficient means in civil cases.” In the debate prior to its enactment the Minister for Equality and Law Reform, stated the purpose of the legislation to be the provision by the Legal Aid Board of legal services in civil matters to persons of limited means, at little or no cost to applicants.

The background to the provision of a civil legal aid and advice scheme in Ireland rested initially with the Pringle Committee which was established by the Minister for Justice in 1974. During the time the Pringle Committee was sitting the seminal case Airey v. Ireland [1979] 2 EHRR 305 was initiated. Josie Airey was seeking a judicial separation from her husband and was unable to afford the cost of representation in the High Court which at that stage was the only route through which such a remedy could be obtained. In addition, to obtain a judicial separation (known at the time as a divorce a mensa et thoro, a “divorce from bread and board” that did not confer any right or ability to remarry) required the petitioner to prove fault on one of three grounds on the part of the respondent.

Mrs Airey alleged that in the absence of legal aid in civil matters, coupled with her reduced financial circumstances, she was effectively denied processing her case through the High Court for the purposes of obtaining a judicial separation. It was further alleged that the absence of legal aid in civil matters, as a matter of personal legal right, contravened Articles 1, 6, 8 and 14 of the Convention on Human Rights. In summary, the Court held for Mrs Airey and in a unanimous judgement declared that the State had failed in its duty to her, as a citizen, in not providing her with the means of acquiring legal representation through a State funded process – the legal representation being necessary in the light of the complexity of the judicial process.

The Pringle Committee completed its report in 1977 and recommended that legal aid should be made available to eligible persons in relation to all civil proceedings, including tribunals, inquests and arbitrations.

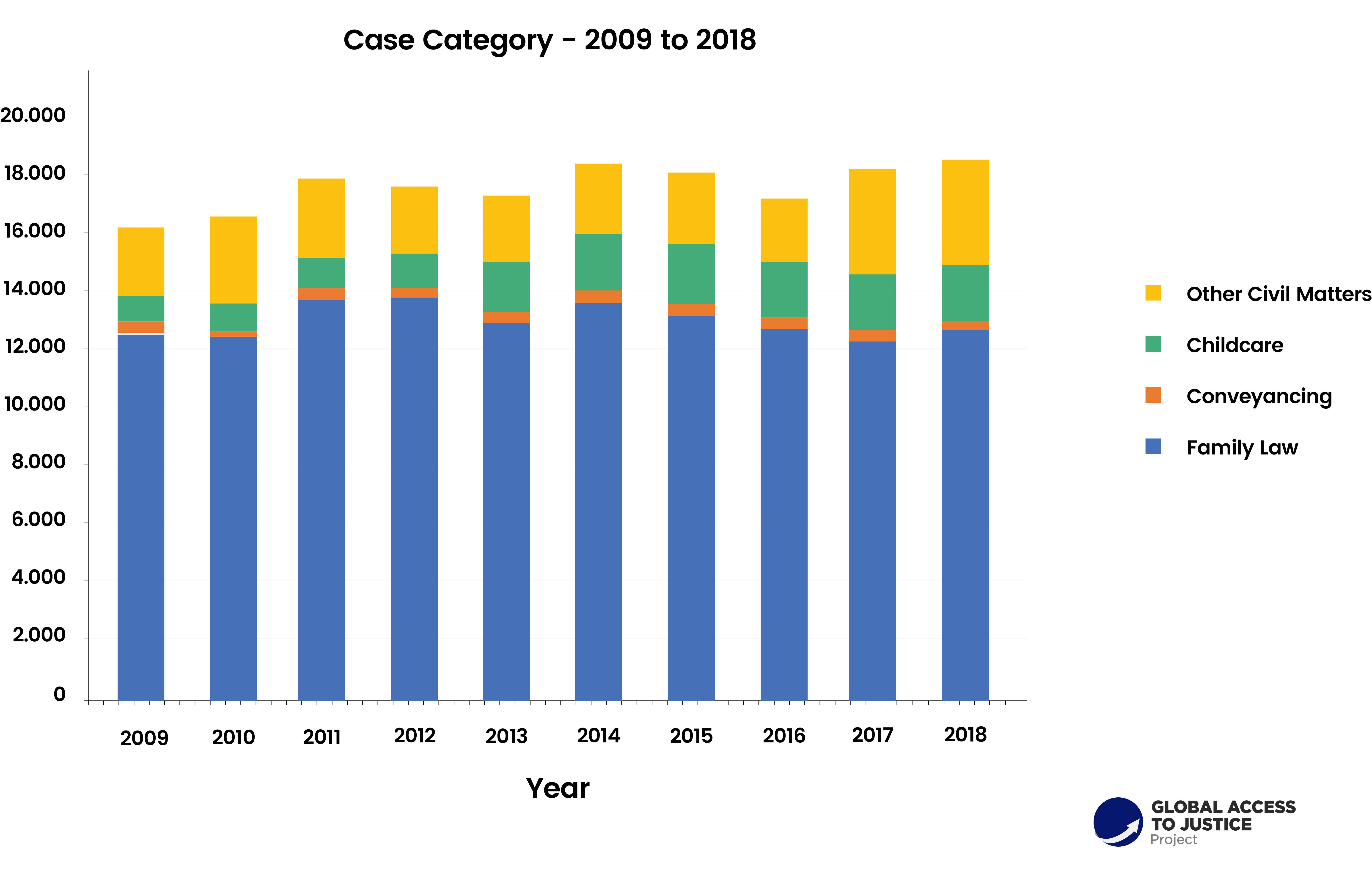

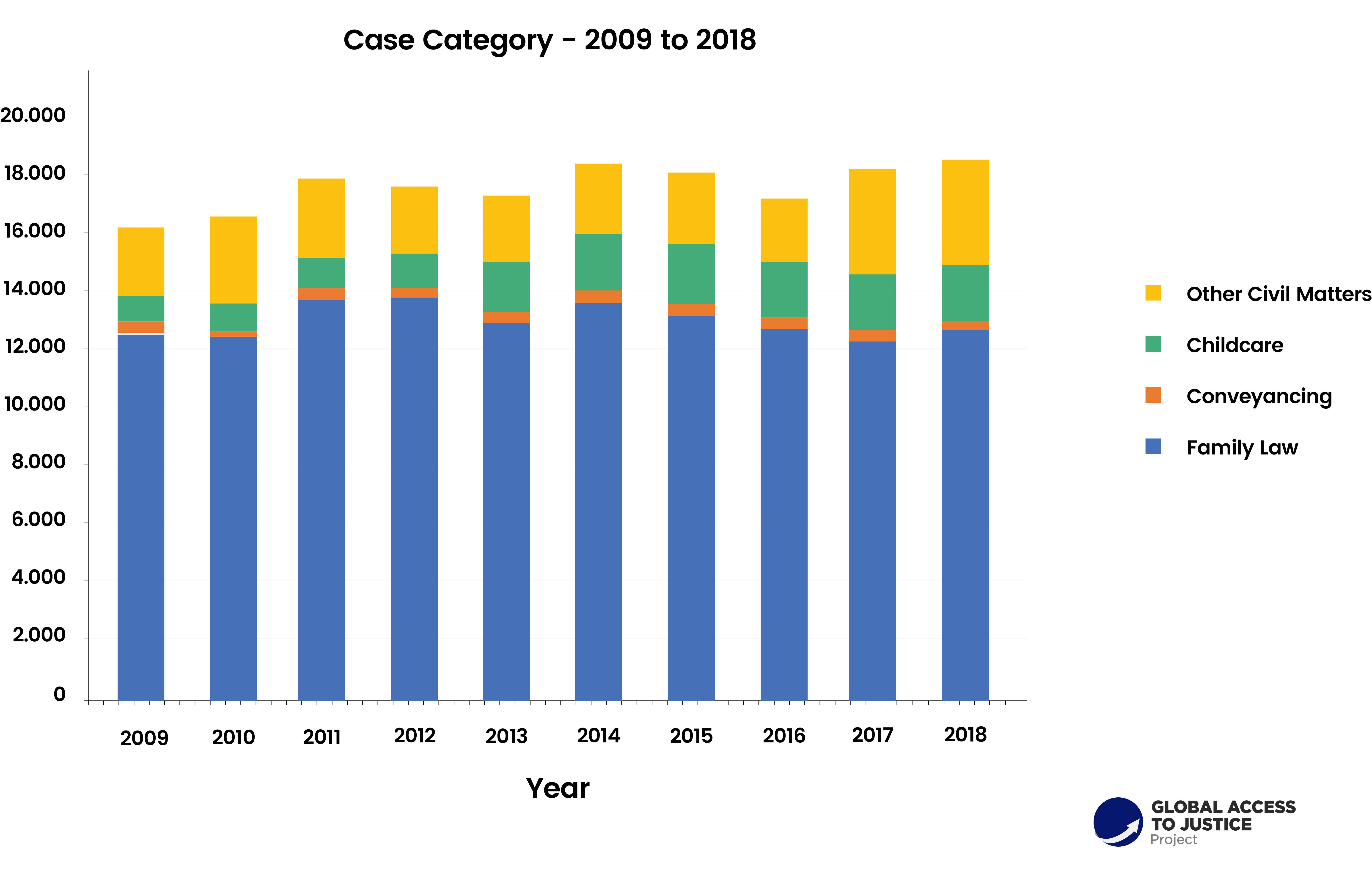

The Scheme established a Legal Aid Board on 21st December 1979. The model recommended by the Pringle Committee was an “in-house model” in which all solicitors were initially employed by the Legal Aid Board and provided services out of local offices known as law centres. Eight such centres were initially established in Dublin and a number of major cities. While this model slowly expanded to fifteen centres by 1990, it was not until a period between 1994 and 1997 that the Board expanded to approximately its present number of law centres, with fifteen centres opened within a relatively short period of time. The impetus for this came from the transfer of jurisdiction in judicial separation cases to the Circuit Court in 1989 (which was accompanied by the introduction of “no-fault” grounds and a major reform of procedure in the area) swiftly followed by the introduction of divorce in Ireland in 1995. Around this time the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995, which placed the scheme on a statutory basis was also enacted and it came into force on the 11th October 1996. It was supplemented by the Civil Legal Aid Regulations 1996 which came into operation on the same date.

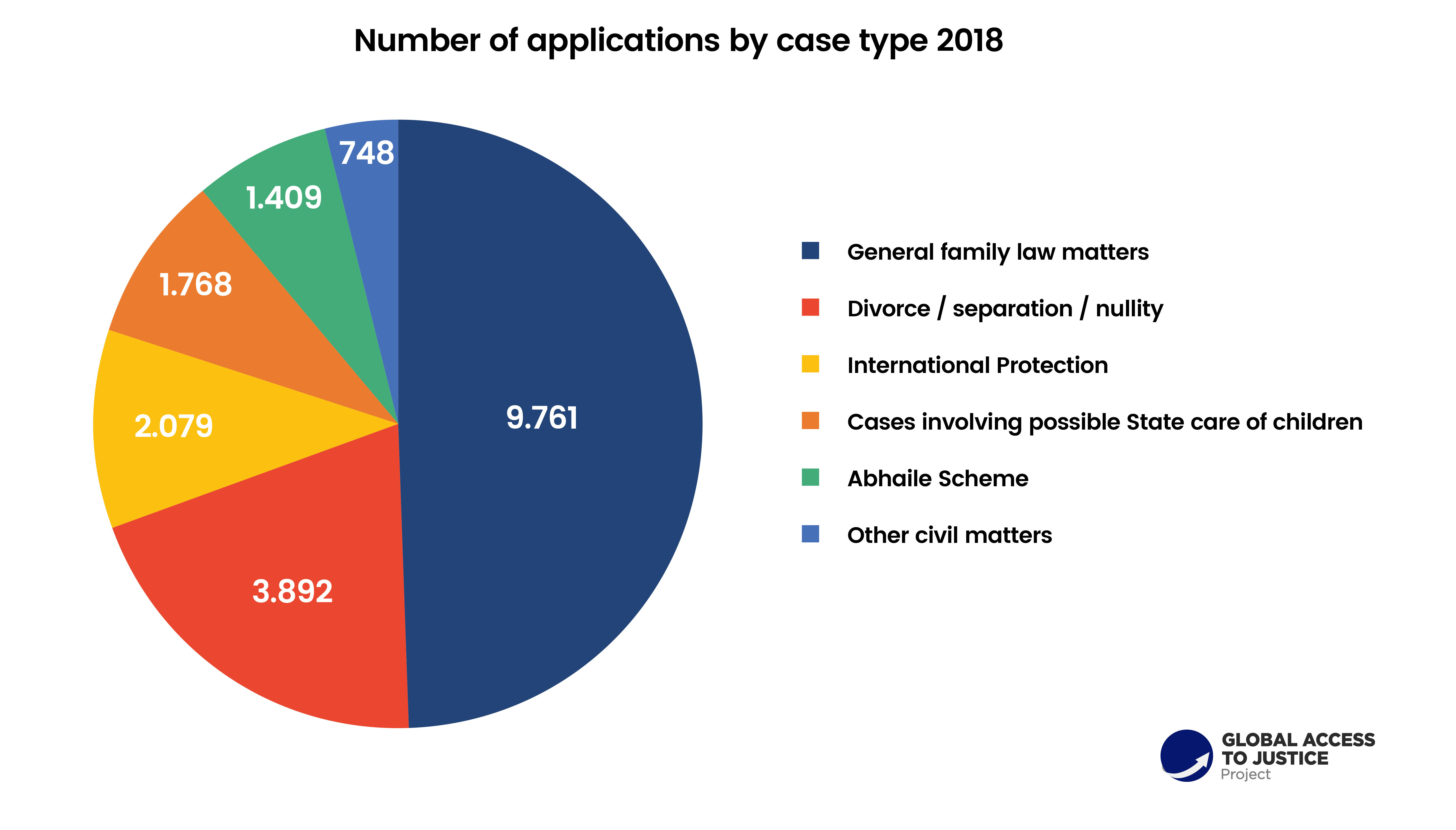

In 1999, on foot of a major increase in the number of persons seeking asylum in Ireland (which increased from approximately 30 persons per annum to a height of over 12,000 in the space of a decade), the Legal Aid Board established a specialist service for asylum seekers. It also opened specialist offices dealing with clinical negligence cases in 2006, public law child care cases in 2011 and personal injuries in 2014. Although originally a fully in-house service civil legal aid in Ireland has migrated over a period of time to a “mixed model” whereby private lawyers provide services in certain areas (particularly family law matters in the District Court and international protection cases) and law centres continue to provide services in other matters, particularly judicial separation and divorce cases. Civil legal aid became available for inquests in 2014. In 2016 a time-limited scheme of legal and financial assistance for insolvent persons facing the loss of their home on account of mortgage arrears was commenced.

5.1.2. Criminal legal aid

Prior to the introduction of legislation in 1962 there was no statutory basis for the provision of financial aid to persons without the means to pay for legal representation in order to defend themselves in criminal proceedings. Such representation as was available was provided by lawyers on an ad hoc basis. Legal aid, paid for by the State, was restricted to persons who were clearly without financial means and where the charge against them was one of murder or in cases of a re-trial.

The State’s first legislation in this area – the Criminal Justice (Legal Aid) Act 1962 – provided for the granting by the courts of free legal aid to defendants in a broader range of circumstances, but subject to meeting certain criteria. At the Second Stage of the Bill on 15 February 1962, the Minister for Justice said that the object of the Bill was:

“to introduce a scheme of free legal aid in certain criminal cases. It involves a radical departure from the present arrangements which allow free legal aid only to poor persons accused of murder and also in certain cases where a new trial is ordered by the Court of Criminal Appeal or the Supreme Court. Although the scheme is new, and therefore to some extent experimental, it is comprehensive in character and provides not only for legal aid in criminal courts of first instance but also in the various courts of appeal”.

The Minister went on to say:

“The situation does not … call for the grant of free legal aid in every criminal case. … For example, free legal aid could not be justified in the case of experienced criminals … who have deliberately decided to make a living of crime”.[1]

That was a somewhat tentative start and indicates that the intention was probably to confine free legal aid to a limited category of cases. However, the Oireachtas was obviously conscious of the rights of accused persons to have legal representation since the Bill, at section 2, provided that once quite basic criteria were satisfied, the Courts shall grant a certificate of entitlement to free legal aid.

The 1962 Act was duly passed but was not commenced until 1 April 1965.[2] Earlier that year the Criminal Justice (Legal Aid) Regulations 1965[3] had been signed by the Ministers for Justice and Finance which laid down conditions for the operation of the legal aid scheme, the fees and expenses (including reasonable disbursements) payable to solicitors and fees payable to counsel for work under the Scheme. In addition, the Regulations provided for the payment of certain expenses of defence witnesses. These Regulations still form the main basis of the operation of the Scheme.

There has not been a significant restructuring of the criminal legal aid scheme since its inception. The Government took a decision in principle to transfer the operation of the Scheme to the Legal Aid Board in 2010 but this has not occurred to date although responsibility for three ad-hoc schemes (one of which relates to judicial review and habeas corpus-type applications that arise in criminal proceedings, another of which relates to actions for the recovery of the proceeds of crime, and the final being the police station advice scheme described elsewhere in this report) were transferred to the Board between 2011-12. In addition, calls are periodically made for the establishment of a Public Defender Service and while the Programme for Government 2016 contained a commitment to investigate the establishment of such a service no concrete proposals emerged in the lifetime of the 32nd Dáil.

5.1.3. State-funded family mediation

A state-funded family mediation service was established under the auspices of the Department of Justice and Equality. Although from the outset the service was free of charge and open to all it was initially provided only from one location in Dublin city centre with just four part time mediators employed. The service did not expand until the 1990s and was finally placed on a statutory footing under the Family Support Agency Act 2001.

On foot of an impending decision to transfer most of the Family Support Agency’s other functions to a soon-to-be-established Child and Family Agency, and soon after the successful implementation of a scheme to encourage the use of mediation in family law cases in Dublin, responsibility for the provision of State-funded family mediation was transferred to the Legal Aid Board under the Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2011. Upon the commencement of the Act the Board took over responsibility for a nationwide network of sixteen mediation offices from the former Family Support Agency, sitting alongside its existing responsibility for the provision of civil legal aid and advice. The management staff, mediators, and associated clerical staff transferred to the Board. It brought a mechanism for Alternative Dispute Resolution under the auspices of the Board as another means of service delivery. Since the transfer the Legal Aid Board has piloted initiatives for the encouragement of the use of family mediation as a means of resolving disputes, including the co-location of family mediation and civil legal aid offices on the same site.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

Article 38.1 of the Bunreacht na hÉireann (Eng: the Constitution of Ireland) states:

“No person shall be tried on any criminal charge save in due course of law”

In the Supreme Court judgment The State (Healy) v. Donoghue, [1976] IR 325 O’Higgins CJ considered the provisions of Article 38 in conjunction with Articles 34 and 40 in relation to the functions of the courts and fundamental rights, respectively. The Court found that Article 38 in that context made it:

“mandatory that every criminal trial shall be conducted in accordance with the concept of justice, that the procedures applied shall be fair, and that the person accused will be afforded every opportunity to defend himself….and the person charged must be afforded the opportunity of being represented. This opportunity must be provided by the State”.

The landmark judgment also referred to the European Convention on Human Rights[4] and jurisprudence from the United States[5] which confirmed that in a criminal trial for a serious offence the right of an indigent defendant to have the assistance of counsel is a fundamental right. The Supreme Court concluded unanimously that the conviction of John Healy must be quashed due to the absence of legal representation.

In summary, the court judgments have moved the State’s approach on from the initial, rather restricted, approach in the 1960s to an acceptance that the Constitution requires that a defendant is in a position to fully defend him/herself in criminal proceedings before the Courts, that he be given the opportunity to obtain legal representation and, where necessary, that the State must meet that cost. Therefore, the right or otherwise to criminal legal aid is provided for the Criminal Justice (Legal Aid) Act 1962 with the right or otherwise to civil legal aid is provided for in the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid

5.3.1. Civil legal aid

The Legal Aid Board is a statutory body (a corporation with separate legal personality) established by Parliament under the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995, with responsibility for the provision of legal aid and legal advice to persons of insufficient means in civil cases and for a family mediation service. The Board is appointed by the Minister for Justice and Equality and consists of a Chairperson and twelve other members, two of these members must be practicing barristers, two practising solicitors, and two must be staff members (though not stipulated in the Act, it is normally the practice that one of the staff members is a legal or mediation professional and one is an administrator). Though appointed by the Minister the Board is statutorily independent in the performance of its functions.

The members of the Board operate on a non-executive part-time basis and have responsibility for:

- the strategic direction of the organisation

- determining policy and monitoring its implementation

- overseeing the proper and effective management of the organisation

- monitoring the implementation of effective financial procedures and providing accountability

- approving and monitoring budgets, and

- making certain reserved decisions

Support to both civil legal aid and family mediation service is provided by support staff, based in Head Office.

Administrative structures are headed by a Chief Executive who is responsible for day-to-day operations, and for the execution of policies set by the Board. The Chief Executive reports directly to the Board. A number of senior staff (with the title of Director) report to the Chief Executive, and each has been delegated responsibility for certain functions. These include the overall management of the provision of legal aid, human resources, IT, finance and various other corporate support functions.

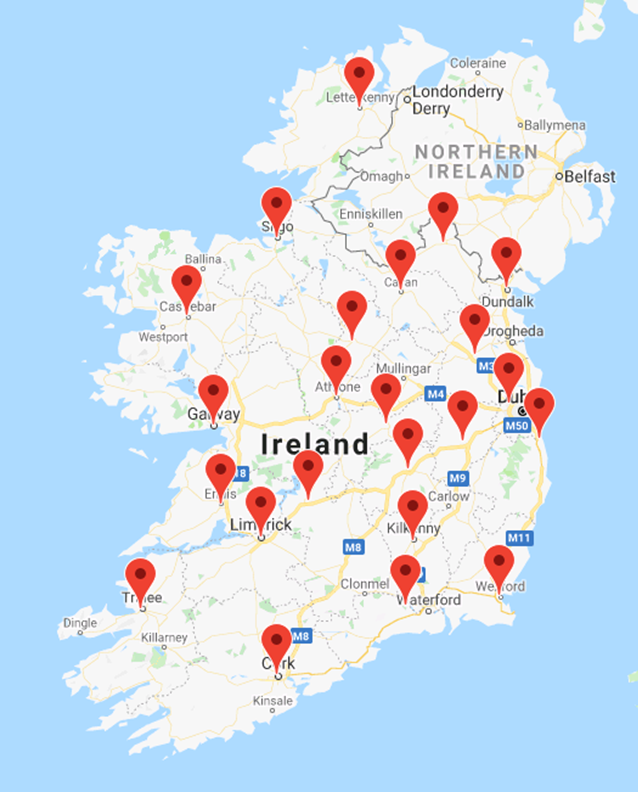

The civil legal aid and advice service is managed by the Director of Civil Legal Aid, who is assisted by two Regional Managers. Legal services are provided by staff in thirty three law centres. These are staffed by solicitors, paralegal, and administrative staff. Each law centre has a managing solicitor who reports either to one of the two Regional Managers or directly to the Director of Civil Legal Aid. Overall, the Board employs about 470 staff.

Alternative dispute resolution is provided for through the Board’s Family mediation services which are managed by the Director of Family Mediation. Family mediation is provided out of seventeen mediation offices, staffed by mediators and administrative staff.

Section 5 of the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995, provides that:

“The principal functions of the Board shall be… to provide, within the Board’s resources and subject to the other provisions of this Act… legal aid and advice in civil cases to persons who satisfy the requirements of this Act, and… a family mediation service;”

The Board is required to act under the Act and Regulations at all times and has no power to vary the requirements unless the Act and Regulations provide that the Board can do so. The Board does, from time to time, make submissions to the Minister for Justice and Equality for amendments to the Act or Regulations in light of experience gained by the Board in the provision of the service. Those amendments are a matter for Government and the Board must continue to Act within the terms of the Act and Regulations unless so amended.

5.3.2. Criminal legal aid

There is no single institution formally established for the delivery of criminal legal aid services generally. The Minister for Justice and Equality retains the policy responsibility for criminal legal aid and the Department of Justice and Equality makes payments to legal practitioners. However the responsibility of deciding who should be granted legal aid in criminal cases rests with individual judges, while County Registrars are responsible for registering providers of criminal legal aid. There is a long-standing Government decision to transfer formal responsibility for the provision of criminal legal aid services to the Legal Aid Board but the necessary legislation to do so has yet to be brought forward.

By agreement with the Minister for Justice and Equality, the Legal Aid Board operates (on an administrative basis only and without any formal legal responsibility having been conferred by Parliament) three ad-hoc schemes dealing with legal advice in police stations, defence of civil actions for to the recovery of the proceeds of crime, and the making of certain civil applications arising in criminal matters primarily of a judicial review or habeas corpus-type nature.

5.3.3. Delivery of criminal legal aid services

The courts, through the judiciary, are responsible for the granting of criminal legal aid. Aside from a discretionary financial test, the court must also be satisfied that by reason of the ‘gravity of the charge’ or ‘exceptional circumstances’ it is essential in the interests of justice that the applicant should have legal aid. Criminal legal aid is provided by private solicitors willing to provide the service who subsequently claim payment from the Department of Justice and Equality.

5.3.4. Delivery of civil legal services

Civil legal aid is provided through the Board’s law centre network throughout Ireland. In some cases, civil legal aid is provided through solicitors in private practice who have agreed with the Board to provide service according to prescribed terms and conditions and to be placed on a panel of solicitors maintained by the Board.

At the time of writing the Board had 132 solicitors employed and 58 paralegals and the Board had circa 2,300 entries on its various panels (some private solicitors provide legal aid across several panels and several geographical areas so 2,300 is representative of entries on the panels rather than individual solicitors providing the service).

5.3.5. Development strategy – civil legal aid

A major development strategy of the Legal Aid Board over the past ten years has been the promotion of alternative dispute resolution in family law disputes. Responsibility for the provision of State-funded family mediation was transferred to the Legal Aid Board under the Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2011. Upon the commencement of the Act the Board took over responsibility for a nationwide network of sixteen mediation offices from the former Family Support Agency, sitting alongside its existing responsibility for the provision of civil legal aid and advice. The management staff, mediators, and associated clerical staff transferred to the Board. It brought a mechanism for Alternative Dispute Resolution under the auspices of the Board as another means of service delivery and thus widened the strategic direction of the Board. Since the transfer the Legal Aid Board has investigated and piloted initiatives for the encouragement of the use of family mediation as a means of resolving disputes, including the co-location of family mediation and civil legal aid offices on the same site.

5.3.6. Evaluation of State-funded civil legal services

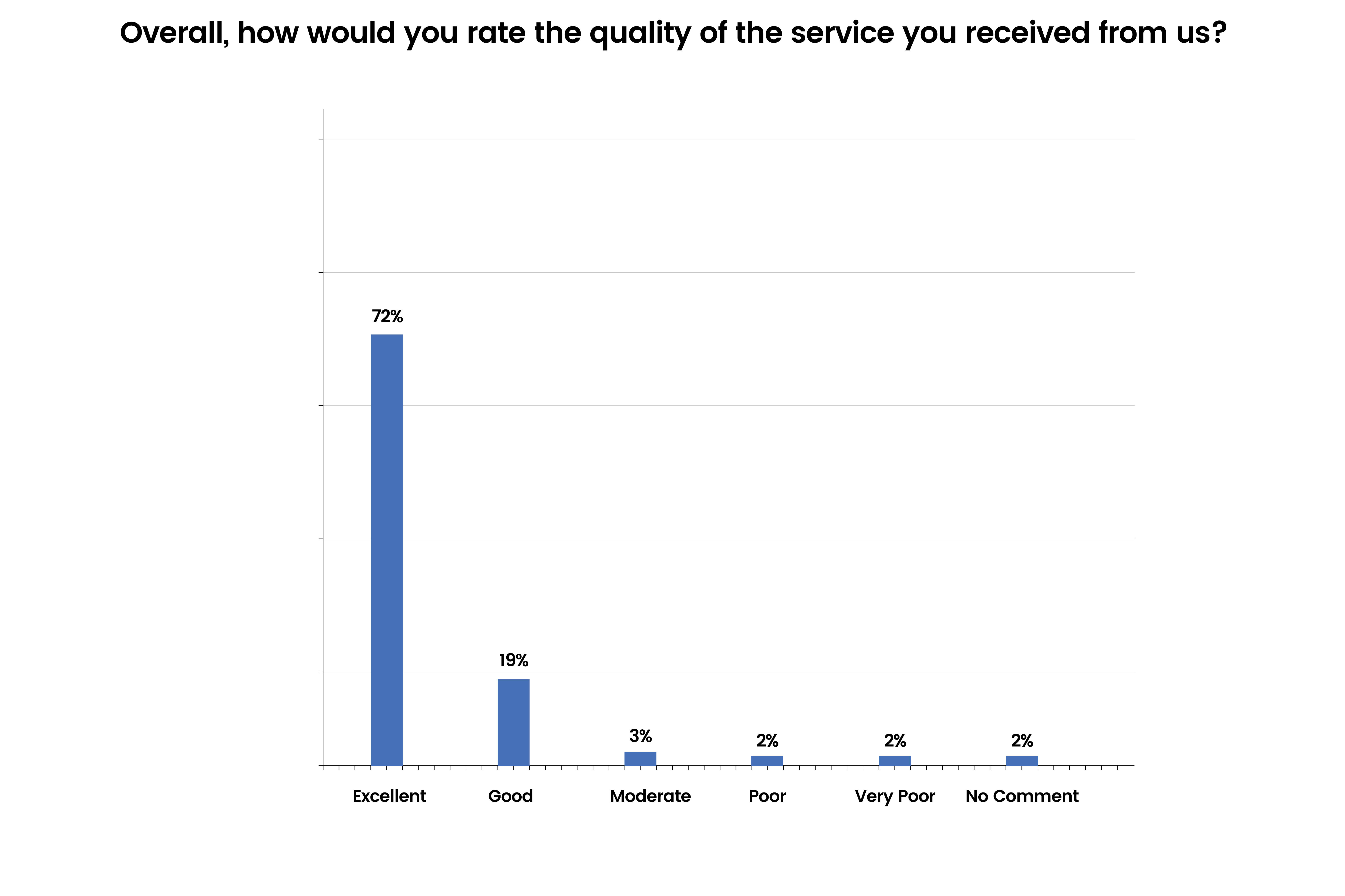

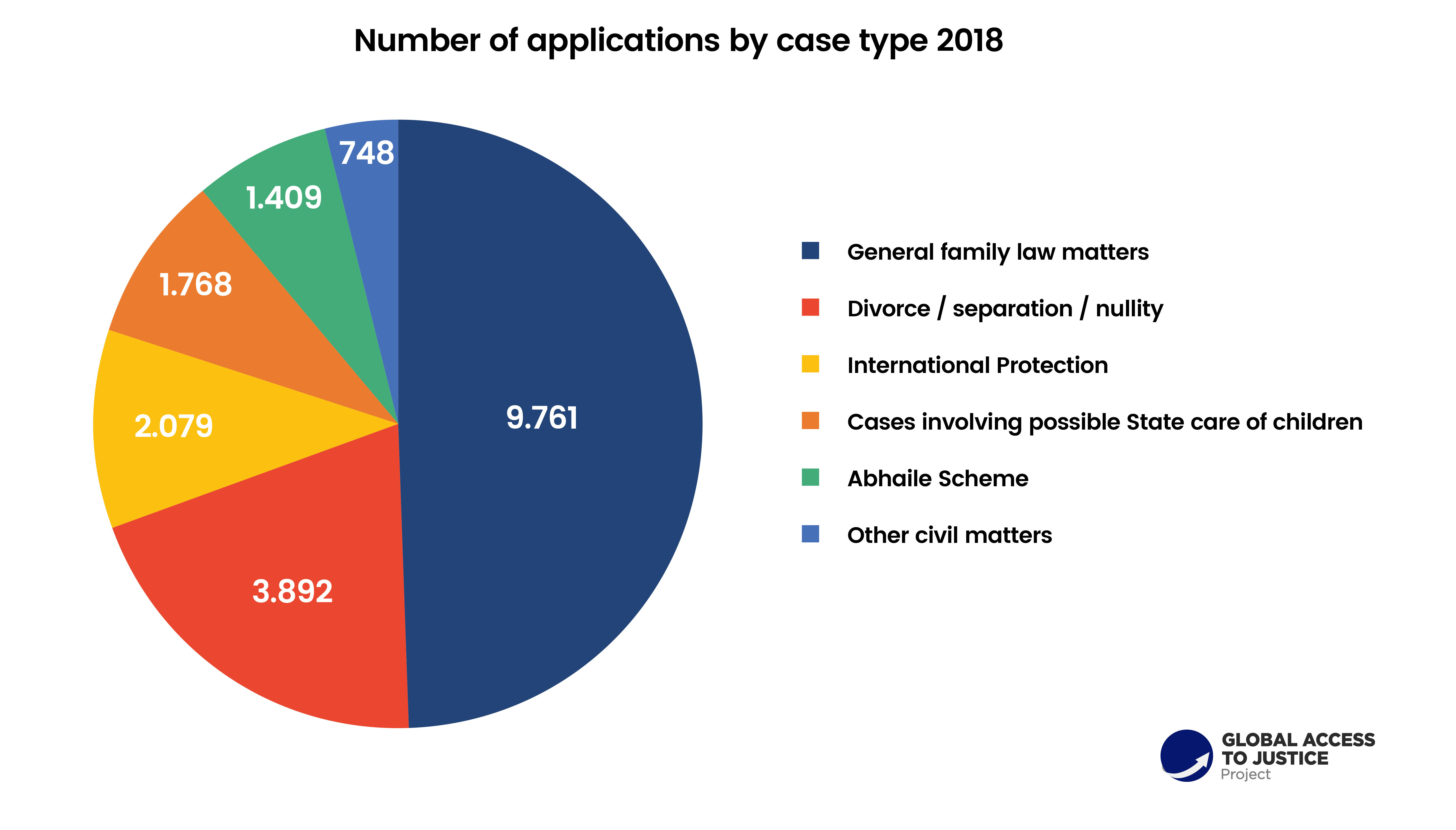

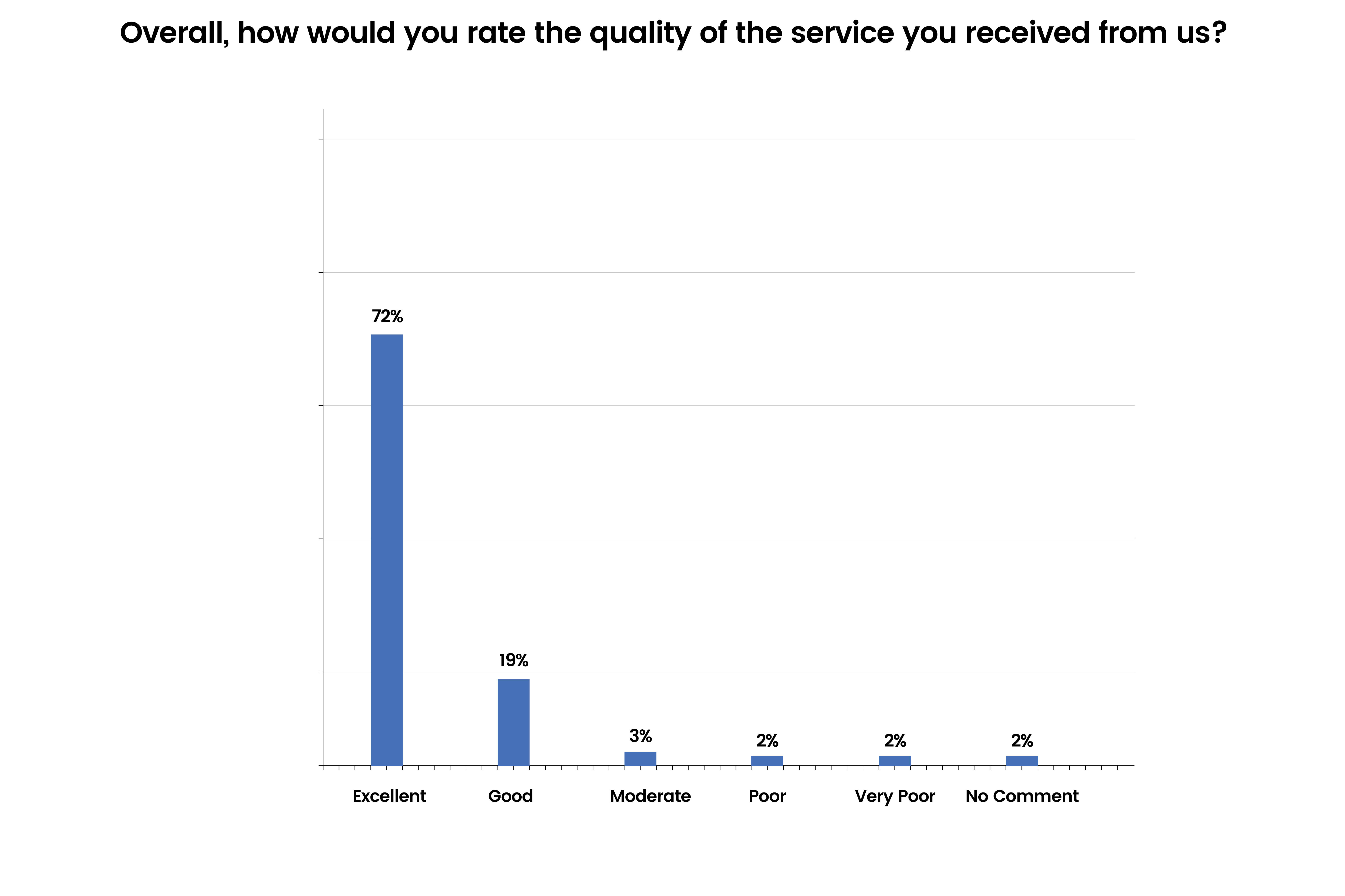

The Legal Aid Board operates a customer comment card programme whereby clients of the Board can evaluate their experience of the institution at the conclusion of legal services. The Board recently completed a research project evaluating client perceptions of the Board via the customer comment card programme. The findings were as follows:

Overall the 95 Clients report having a very positive experience, with 91% rating the service they received either good or excellent. In addition to that, 12 (32%) of the Clients left further comments commending the excellent, helpful service.

Positive comments from client’s commended the “great service” received and to “keep up the good work”. Others found that the service was “very informative and helpful” and that they felt they “always felt in good hands”. Many comments also noted the scale of the work that was being put into cases and were extremely appreciative of same.

Chart 13. Evaluation of State-funded civil legal services

5.4. Legal aid budget

5.4.1. Civil legal aid

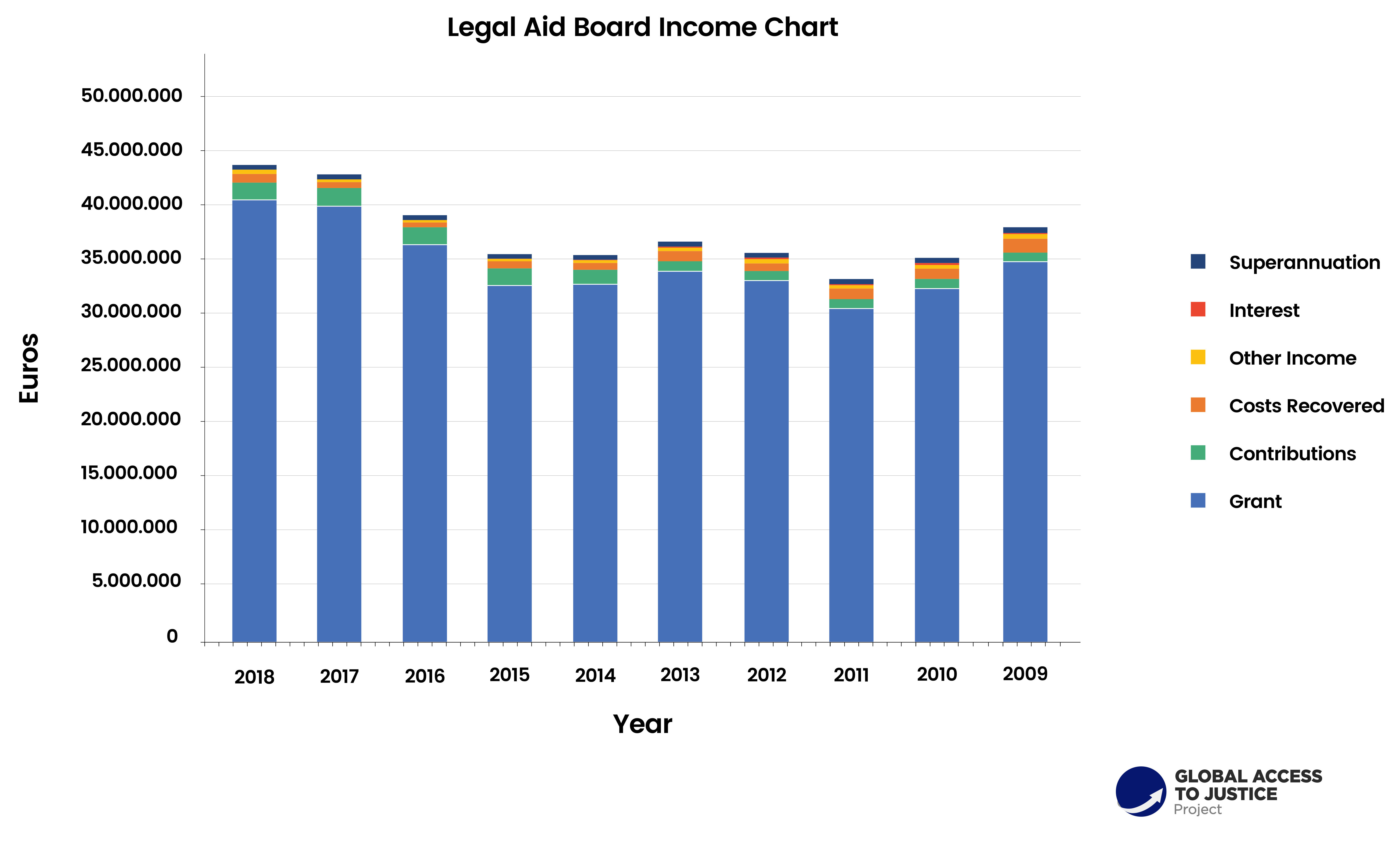

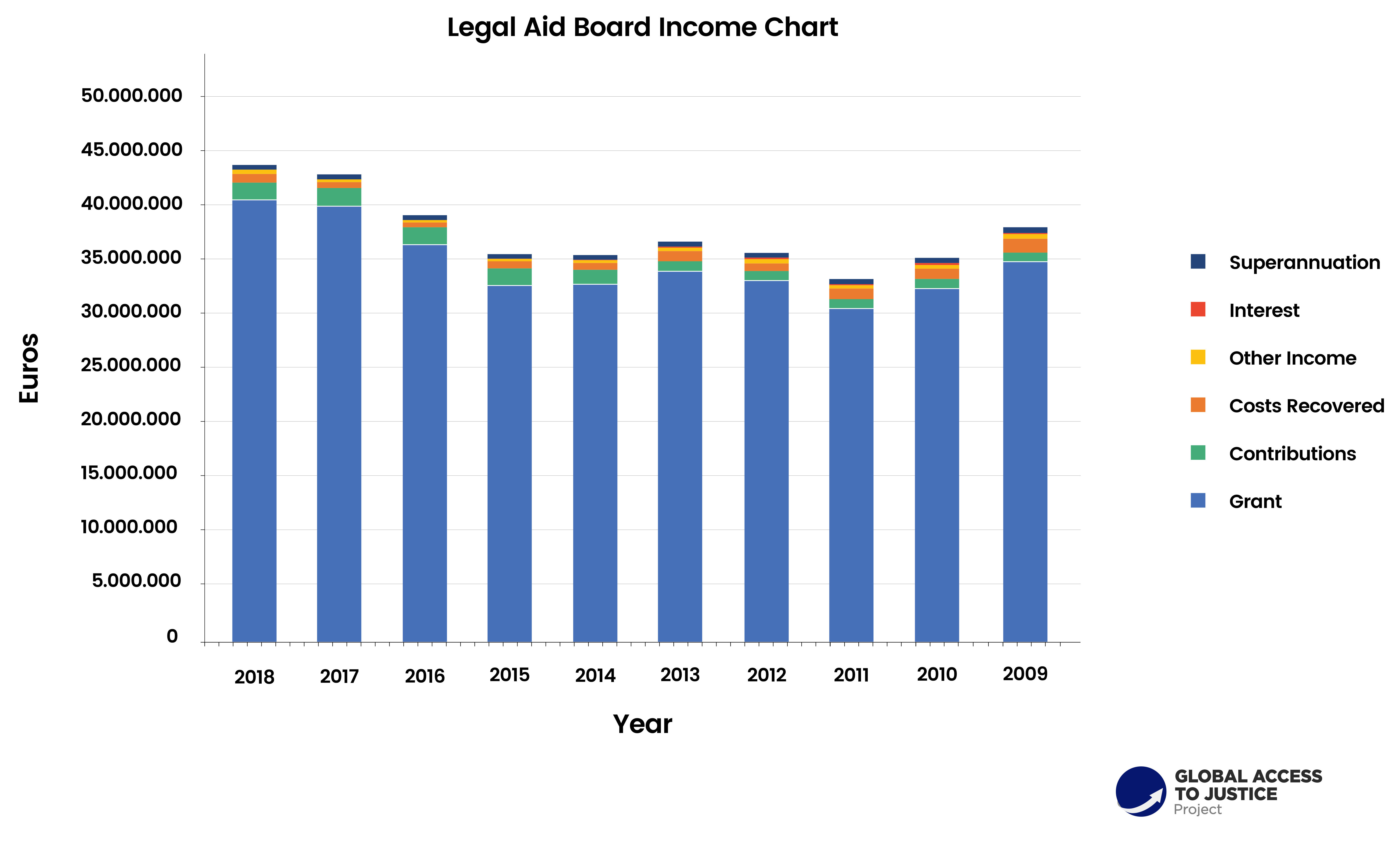

The Legal Aid Board is funded primarily through the following sources of income:

- Annual grant from the Irish State

- Contributions by clients to legal services

- Costs recovered from legally aided proceedings

- Other income

The Board’s funding is ultimately a mixture of State-funding and self-funding, with State-funding making up the overwhelming contribution and the self-funded aspects a relatively small portion.

5.4.2. Grant

As in most Westminster-style political systems all institutions of State operate from funds (supply) which is ultimately provided by Parliament. The Minister for Finance brings forward the annual State budget to the House of Representatives (Dáil Éireann) each autumn in a similar manner to Westminster systems and it is generally approved (a vote against the State budget is regarded as effectively a vote of no-confidence in the Government and would almost certainly trigger a general election). The position at present is that Parliament does not allocate money specifically for the Legal Aid Board. Instead Parliament provides money to the Minister for Justice and Equality and he in turn provides a portion of that money as a grant to the Legal Aid Board. Therefore in practice, the setting of the Legal Aid Board’s annual grant is a matter for the Government. The Legal Aid Board is permitted to make a submission in respect of anticipated funding which may be considered in setting the budget.

5.4.3. Self-funding – contributions and recovery of costs

Except in certain cases all persons granted legal advice and legal aid must pay a contribution towards their legal services. In advice cases this contribution ranges from €30 to €150 and in aid cases from €130 to €5,300. In reality the majority of persons, including all those whose sole form of income is social welfare and who do not own any assets, pay contributions at the minimum of the scale. There is a cap in certain matters which are referred to private solicitors at the applicable fee payable to a private solicitor.

The Board can also recover its costs in one of two scenarios. Firstly there may be an order for costs made by the court in favour of the legally aided person in certain cases. This does not generally arise in family law but may occur in, for example, torts or contract matters. Any award of costs must be paid into the Legal Aid Fund to allow the Board to recover its costs. The second scenario is where money (e.g., damages) or real property is recovered or preserved on the legally aided persons behalf. It is required that any money recovered or preserved be paid into the Fund to allow the recovery of the Board’s costs. In the case of real property the Board may cause a charge to be placed over the property so that the Board will recover its costs as part of a sale of the property. The reality is that due to the procedure involved the Board will rarely seek to do so.

Chart 14. Legal Aid Board Income

While the Board was been largely successful in preserving its grant levels through the downturn of the late 2000s/early 2010s, it was required under the Financial Emergency Measures in the Public Interest Acts 2009-2010 to implement two 8% cuts in fees to all private sector providers. In addition its ability to recruit staff was for a number of years limited by virtue of a “public service recruitment moratorium” in which there was a general bar on public service bodies taking on any new staff. The Board obtained some limited exemptions to this to allow targeted recruitment of solicitors.

5.5. Legal aid providers

Solicitors for civil legal aid are required to hold a current practicing certificate from the Law Society of Ireland. Any barrister wishing to provide civil legal aid services must be admitted to practice by the Chief Justice of Ireland.