National Report

Summary of Contents

1. GENERAL INFORMATION

France is a decentralised state under the 1958 Constitution. Its political system is a hybrid between a presidential state and a representative democracy.[1] On 1st January 2020, the French population counts 32,397,179 men and 34,666,524 women, making it altogether 67,063,703 individuals living in Metropolitan France and Overseas territories. Official data about ethnic groups are not available in France. However, statistics exist based on the country of origins. In 2018, 6,5 millions of immigrants were living in France (ie 9.7 % of the total population). Foreigners living in France amounted to 4,8 milions (ie 7.1% of the population).[2] French is the official language in France.[3] According to Article 1 of the French Constitution, France is a secular republic. The principle of laïcity is a key feature of the French legal system. However, in sociological terms, the Observatory for religious freedom (Observatoire de la liberté religieuse), a website curated by the Catholic church all over the world, estimates that 64.7 % of French are Christians, 19.9 % Agnostics, 8.8 % Muslims, 2.4 % Atheists.[4]

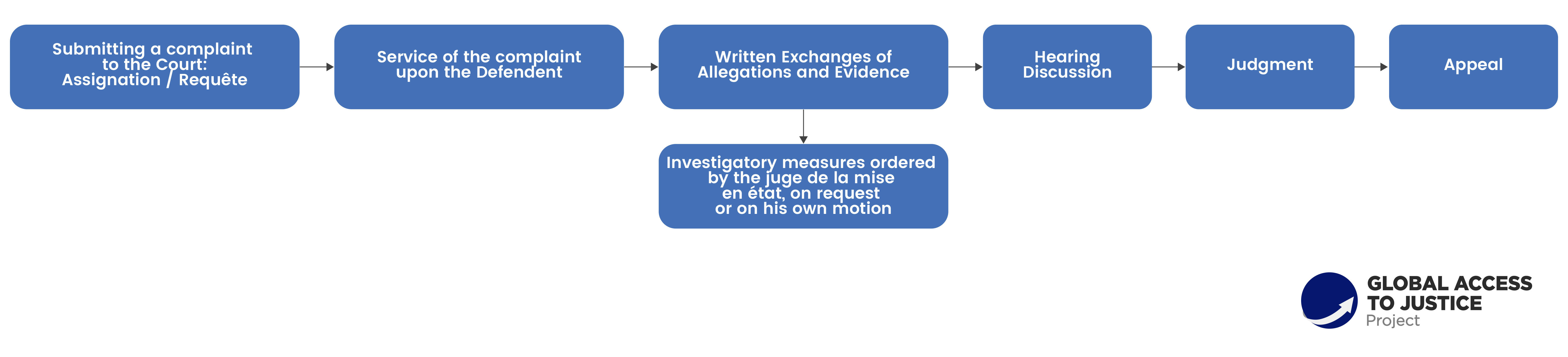

In economic terms, the French GDP has been increasing from 35,203 $ per capita in 2008 to 46,242 $ per capita in 2018.[5]

Chart 1. Evolution of GDP per capita (2008-2018)

Other socio-economic factors can be broken down as follows. The Gross National Income per capita is 40,511 $ (in 2011). The inequality index is 0.809, while no data is available on poverty. The life expectancy at birth is 82.5 years. The expected years of schooling are 15.5 and the mean years of schooling 11.4. The overall human development index is 0.891, making France ranking 26th in the rankings of the UN Development Programme.[6]

2. LEGAL SYSTEM

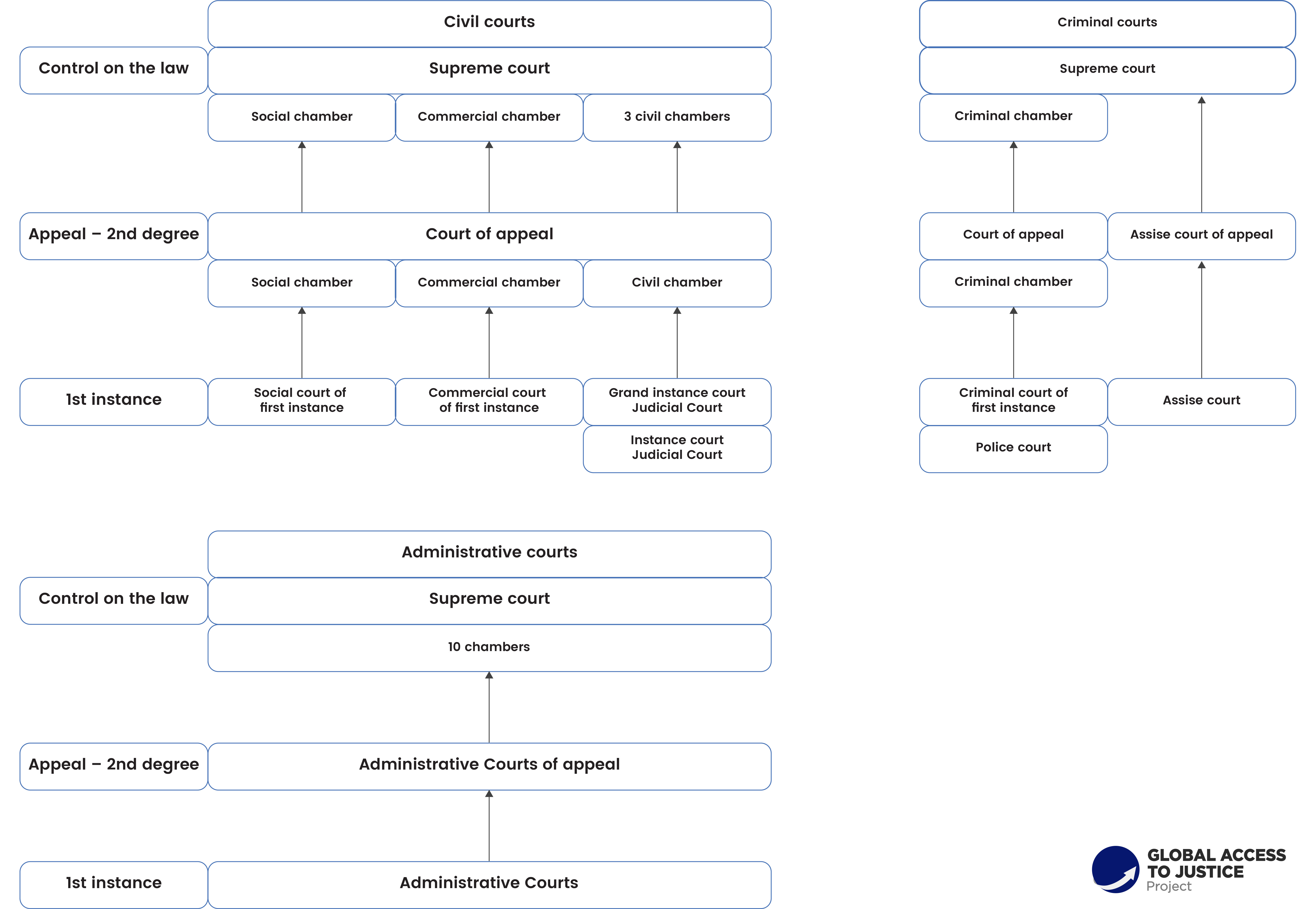

France is a civil law system. Its justice system is organised along a pyramidal system, divided into two branches, the administrative branch and the judicial branch.

The administrative branch includes an Administrative Supreme Court (Conseil d’Etat) on top of the pyramid, eight administrative appeal courts (cours administratives d’appel) and 42 administrative courts (tribunaux administratifs) across the country. The administrative branch has jurisdiction over claims from litigants against the State and all administrative bodies. In 2018, administrative courts ruled over 252,055 cases.[1]

The judicial branch includes a Supreme Court (Cour de cassation) on top of the pyramid, 36 appeal courts (cour d’appel) across the country and 164 judiciary first instance courts (tribunaux judiciaires) and police first instance courts (tribunaux de police) and 210 social first instance courts (conseils des prud’hommes) across the country. In 2018, the Grand instance courts (tribunaux de grande instance) gained 878,586 new cases and the instance courts 388,655.[2] 4,687,990 reports of offences (procès-verbaux) were processed by the prosecuting units (parquets). Criminal first instance courts (tribunaux correctionnels) decided on 630,562 cases. Assise courts (cours d’assises) processed 2,932 cases (including 539 appeal court cases).[3]

On 01.01.2020 the Grand instance court and the instance court were merged into a “judicial court of first instance” (tribunaux judiciaires). The proximity chambers (tribunaux de proximité) may replace instance courts in cities in which there are no Grand instance courts.

Chart 2. Organisational Chart of French Judicial System[4]

The legal profession is organised around lawyers (avocats) who have two main functions: first, to assist parties during a trial or judicial proceedings; second, to act in the name of clients and advise them for legal decisions. Each lawyer is a member of a regional bar (barreau) connected to judicial courts in the region. One key feature of the legal profession is the independence that lawyers need to have. This was the main ground on which the National Bar Council (Conseil national des Barreaux) rejected the idea of alternative business structures (where non-lawyers can partly own capital and/or enjoy voting rights in the association) in 2012.[5] However, discussions about a possible reorganisation of the legal professions with cogent professions (such as notaires and huissiers de justice) have been debated since 2008. An official report advised against such a fusion as the professions were too different in nature to allow for success.[6] This led to a different approach in 2015: that of “pluri-professionality”. A 2015 act allows the Government to facilitate the setting up of corporations for a common exercise of various professions related to the law (such as auditors or experts in intellectual property).[7] The system is currently being implemented. As the legal profession is currently facing social and technological transformation, the National Bar Council is engaged in a wide discussion about the future of the profession.[8]

The National Bar Council counts 69,000 lawyers in France.

In principle, access to justice is free in France.[9] However, a litigant has to pay for a range of expenses (lawyer’s fee, translation fees, court’s fees such as copies or registered letters, experts’ fees if not ordered by the court, etc.). Lawyer’s fees can vary a lot. Lawyers are allowed to set their own fees. They can use a range of factors to do so: the financial situation of their client, the complexity of the case, expenses, their own reputation, the time to be spent on the case. Additional costs related to the opening of the file, phone calls, copies, travels etc. can be incurred. Normally, a convention has to be signed between the client and the lawyer from the start of the collaboration, to set the amount of fees and the various expenses that can be reasonably foreseen.[10]

As a matter of principle, legal representation is mandatory.[11] However, there are many exceptions,[12] for instance in front of civil courts if the matter is not within the exclusive jurisdiction of the tribunal judiciaire (family matters for example are within its exclusive jurisdiction) and the amount in controversy does not exceed 10,000 euros. Parties are represented by a legal representative (auxiliaire de justice), who is a registered lawyer.[13]

There is no legal definition of “paralegal” in France. They play no role of legal representation in court cases.

Judges and courts are in principle independent.

Article 64 of the French Constitution provides that the French President guarantees the independence of the judicial branch. The independence of the administrative branch derives from a fundamental principle recognised by the Law of the 24th May 1872 reorganising the Administrative Supreme Court and has been asserted by the French Constitutional Council in 1980.[14]

In the judicial branch, judges are recruited through a competition giving access to a national training programme run by the National School of Judiciary (Ecole nationale de la Magistrature).[15] On 1st April 2017, there were 8,313 judges in France ; in 2019, there were 8,600.[16] 66 % of them are women, but there are variations depending on the age groups.[17] Judges are appointed for life, ie until they reach the official age of retirement. Currently, this age is 67 years old as a matter of principle, and 68 years old for judges in a position of leadership in the judiciary system.[18] As a principle, judges are irremovable.[19] They cannot be moved to other functions, without their agreement, even by way of promotion.[20]

In the administrative branch, judges are recruited through a specific competition, aimed to select magistrates in the administrative courts of first instance and appeal courts. Administrative judges may also come from the National School of Administration (Ecole nationale de l’administration).

According to article 5 of the Ordonnance nr 58-1270 of 22th December 1958 portant loi organique relative au statut de la magistrature, “the prosecutors are placed under the direction and control of their hierarchical heads and under the authority of the Minister of Justice”. This means that they are not independent of the executive powers. The European Court of Human Rights has condemned this situation.[21]

This provision has been challenged in front of the French Constitutional Council. In a 2017 decision, the Council considered that this article provides a good balance between the independence of these judges and the prerogatives of the government under Article 20 of the French Constitution and comply with the French Constitution.[22]

Public prosecutors are recruited in the same manner as judges, through a competition giving access to a national training programme run by the National School of Judiciary (Ecole nationale de la Magistrature) (70%). It is also possible to be exempt of this competition when demonstrating relevant legal experience (30%). Public prosecutors are appointed for an indefinite period of time and the retirement age is set at 67 years. In the evolution of their career, they can become judges, in civil or criminal matters. Judges may also become public prosecutors. They indeed all come from the same formation (see supra: Ecole Nationale de la Magistrature). France has around 2,000 prosecutors out of 8,000 judges, a rate of 2.9 prosecutors per 100,000 inhabitants.

In 2019, the National Bar Council commissioned a survey among the population about their perception of legal services. This survey returned that seven out of ten French found access to the law and justice difficult.[23] However, it is difficult to clearly pinpoint shortages as such in the provision of legal services. The Justice Department is also seeking to better allocate resources in the court system where duplication or low take up of access to justice seem to exist. At the end of 2019, a report to this effect was leaked in relation to social courts of first instance.[24] Yet, this attempt triggered opposition; the Justice Department seems to have backpedalled.

3. PROCESS AND PROCEEDINGS: OVERVIEW

3.1. Criminal Procedure

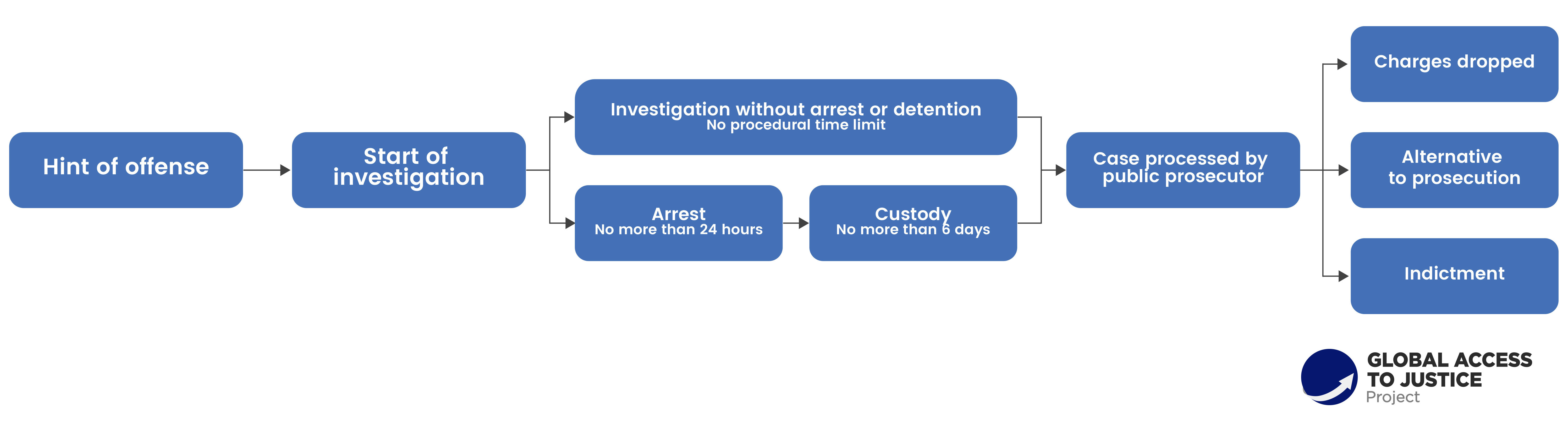

The police investigation is carried out by the judicial police made up of police officers or ‘gendarmes’ (officially belonging to the Ministry of the Interior), either on their own initiative or on that of the public prosecutor.

Whether there is a deprivation of individual freedom or not, the police investigation is under the direction and control of the prosecutor, which means that the latter receives all the minutes drawn during the investigation and that s/he guides the investigators. The prosecutor’s control is reinforced in the event of police custody because s/he is immediately informed of it and authorises any extension of custody.

Any judicial police officer can arrest and place a person in police custody. S/He immediately informs the prosecutor, who can end the custody at any time if s/he deems it necessary.

During the police investigation, any person against whom there are one or more plausible reasons to suspect that s/he has committed or attempted to commit a crime or punishable offense may be arrested and / or placed in police custody.

The period of arrest and detention included is 24 hours, renewable once. Longer duration applies for terrorism, narcotics and organised crime offenses (up to six days). The duration of the ‘flagrance’ inquiry (the most coercive) is eight days renewable once (16 days maximum).

There is no maximum duration for the ‘preliminary’ inquiry which can last several years.

Chart 3. Organizational chart to illustrate the main steps of the criminal investigation phase, and the paths to be adopted at the end of it.

The public prosecutor is the authority responsible for initiating proceedings. On an ancillary basis, the victim can also act and trigger public action through a complaint from a party claiming criminal compensation.

The suspect can only be detained if there are serious and consistent indications of guilt, detention is strictly necessary and the sentence that the law provides for is at least three years in jail. The detention decision must be requested by the prosecutor and is taken by two independent judges.

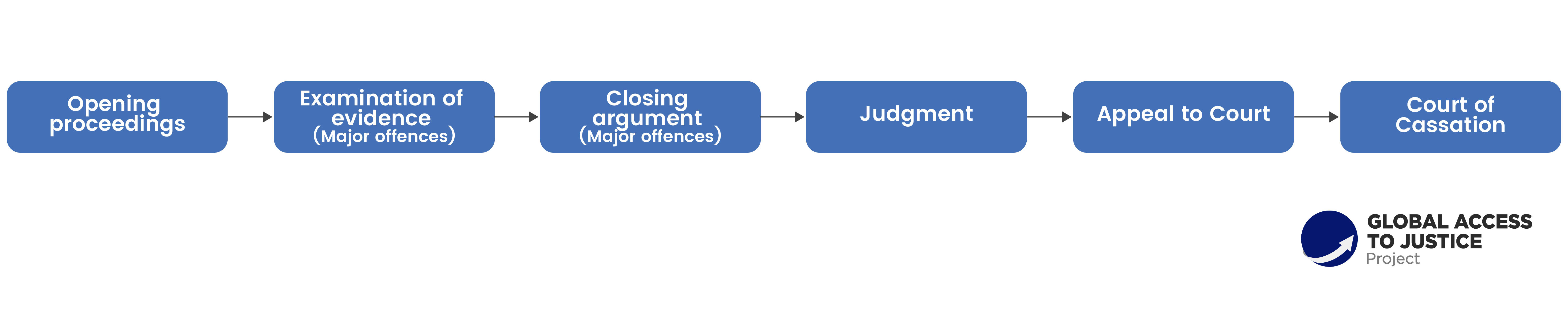

The maximum period of pretrial detention is two years for misdemeanor offences (délits) and four years for crimes.

The French system has not strict system for judgment in absentia (défaut) since 2004. There is a criminal default procedure which allows an individual to be tried for a crime without his/her presence but with that of his/her lawyer. If s/he appears after his/her conviction, s/he has the right to be tried again adversely.

The limitation period for public action is one year for minor offences, six years for misdemeanor offences (délits) and twenty years for crimes.[1] Certain offenses (sexual offenses against minors) have longer time-limit, thirty years. Only crimes against humanity are imprescriptible.

Chart 4. Organizational chart to illustrate the main steps of the criminal procedure

For the most part, France is in compliance with human rights under the European Convention on Human Rights system. In 2018, it was nevertheless convicted 16 times by the European Court, including one conviction for violation of the right to a fair trial (art. 6).

3.2. Civil Procedure

3.2.1. General Procedure

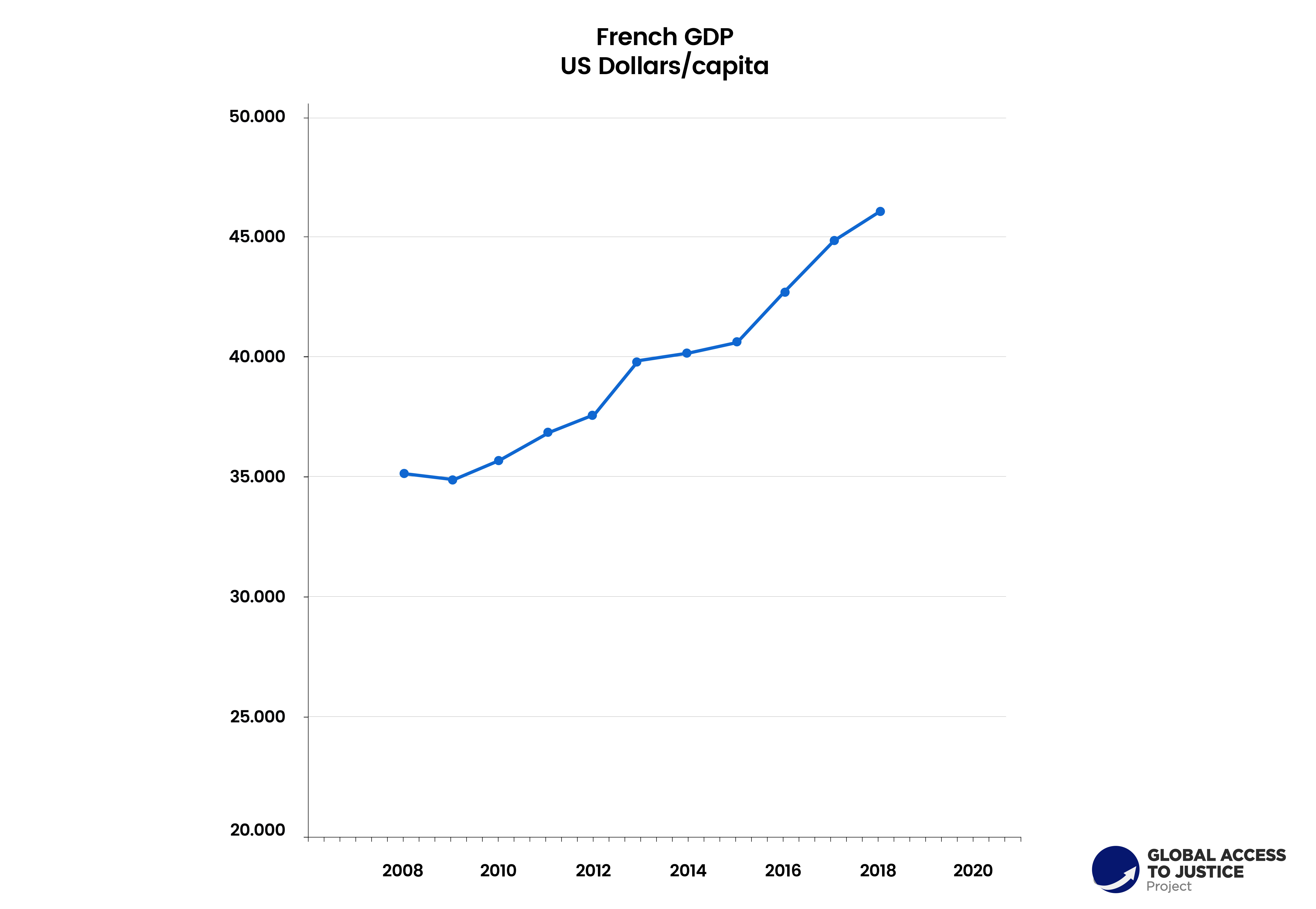

French Civil Procedure has recently been reformed to simplify information for litigants and facilitate access to Courts.[2] Grand instance and Instance courts have merged into Judicial Courts. Within these courts, there is a number of specialised judges: the presiding judge (president) for emergency procedures, accelerated procedures and non-contradictory procedures; the family judge (juge aux affaires familiales); the enforcement judge (juge de l’exécution); the guardianship judge (juge des contentieux de la protection) and the judge of the judicial court (juge du tribunal judiciaire).

It has to be noted that the guardianship judge has also jurisdiction on cases that were previously handled by instance courts. Proximity chambers (tribunaux de proximité), that may replace instance courts in cities in which there are no Grand instance courts, include necessarily a guardianship judge.

As regards the procedure itself, there are two forms of filing a claim: the assignation and the requête. The first one has to be notified to the opposing party by a public officer (huissier de justice) whereas the second one has to be registered to the Court (greffe), who then summons the defendant to appear. The latter is applicable to claims that do not exceed 5,000 euros or for certain specific matters, such as family matters, divorce excluded.

According to Article 750-1 of the Civil Procedure Code, some claims must be preceded in principle by an attempt to reach an agreement through a process of conciliation, mediation or participatory procedure (procédure participative) [see below, section 3.3 on the different procedures].

An investigation process then starts, during which parties exchange their conclusions, known as the mise-en-état process. Conclusions contain their claims, counterclaims and defences, together with the evidence supporting their arguments.

In the ordinary process, a judge of the Judicial Court is appointed specifically to conduct the investigation process, with extensive powers. S/he is the juge de la mise en état. S/he may hear parties, invite them to give further explanation, order any further investigation on his/her own motion. S/he sets the calendar of exchanges, ensures dates are respected and directly rules on requests to deny action (fins de non-recevoir) and exceptions of procedure such as motions to deny jurisdiction or lis pendens exceptions.

The ordinary process is a written process. It means that parties must disclose all their arguments and evidence before any hearing on their case. The hearing normally takes place in front of three judges, except for matters listed at Article R212-8 of the Judicial Organisation Code that are dealt with by one judge.

For matters listed in Article 761 of the Civil Procedure Code, where there is no obligation for the parties to be represented by a registered lawyer (essentially matters previously handled by Instance courts), the process in front of the Judicial court is an oral process, with no specific judge appointed at the investigation stage.

In the written and the oral process, the parties may agree to waive the hearing (articles 778, 828 and 829 of the Civil Procedure Code). There will be no hearing, unless the judges decide otherwise.

Chart 5. Organizational chart to illustrate the main steps of the civil procedure

3.2.2. Specific procedures for urgent matters

In case of emergency, the presiding judge of the Judicial court, or the guardianship judge in the limits of his/her jurisdiction, may grant any interim order, that may be latter reversed or amended in the final decision on the substance of the case. These are called ordonnances de référé.

To be granted such an order, the conditions to be fulfilled by the claimant are given in Articles 834 and 835 of the Civil Procedure Code. The claimant must demonstrate either that:

- There is no serious dispute (the solution is obvious); in that case, even in the absence of emergency, the judge may grant a provision to the creditor or order the enforcement of the obligation; or

- The dispute itself requires an urgent measure to be stabilized: the nomination of a provisional administrator for instance; or

- There is a serious dispute but an urgent provisional measure is necessary to prevent an imminent damage from arising or to put an end to a manifestly unlawful disorder.

In those procedures, the defendant is heard.

The judges may also order “on request” (ordonnances sur requête) any urgent measure in cases where the claimant has good reasons not to inform the defendant of the procedure (to avoid the destruction of evidence or the disappearance of assets for instance). This is then a non-contradictory procedure.

There is also a possibility for the claimant to have an urgent decision on the substance of the case: this is the “procédure accélérée au fond” in cases specifically provided by laws or regulations (Article 839 of the Civil Procedure Code). For instance, the revocation of directors in a limited company must follow this procedure (article L. 225-32 of the Commerce Code).

3.3. Alternative Dispute Resolution

The latest decades revealed an increasing incitement for alternative dispute resolution. Alternative Dispute Resolution is aimed to spare time and costs of a judicial litigation and provides a better solution for the parties to solve their dispute. This is seen to be beneficial for the State, which spares money in the funding of Justice, and for the parties.[3]

There is now an obligation, deriving from Article 750-1 of the Civil Procedure Code, for the claimant to show in his/her claim all attempts made to reach an agreement through a process of Justice conciliation, mediation or participatory procedure (procedure participative). If not, the claim may be declared inadmissible by the judge, on his/her own motion.

The cases concerned are those where the amount in controversy is under 5,000 euros and several disputes between neighbours (articles R. 211-3-4 et R. 211-3-8 of the Judicial Organisation Code). Exceptions are provided, in particular if there is a “just reason” (motif légitime) not to have done such attempts, as a situation of emergency or the use of non-contradictory proceedings.

Furthermore, for all cases, throughout the process, Justice conciliators may intervene on request of the judge or the parties.[4] Judges have also always the power to conciliate themselves the parties.[5]

Justice conciliators aim to find amicable settlement between parties (Article R131‑12 of the Judicial Organisation Code). Their status is organised by regulations.[6] They are volunteers, recruited directly by judges and appointed for a first term of one year, renewable, each time for three years. Each appeal court has a list of conciliators exercising in its jurisdiction. Any adult may apply to become Justice conciliator, provided s/he has experience in the legal field and is not exercising any judicial function. The conciliator then has to follow a one-day formation given by the National School of Magistrates (Ecole Nationale de la Magistrature) the first year and then once each renewed term. Conciliators receive an indemnity to cover their costs. The conciliation is confidential and free of charge for the parties.

Mediation may also intervene throughout the process. The judge may indeed transfer all cases to a third party, the mediator, with the consent of parties.[7] The mediator is a private person or a legal person. While the mediator hears the case, it is not removed from the judge, who has the power to order any measure. The judge specifies the duration of the mediation, which initially cannot exceed three months. This first period may be renewed, at the request of the mediator. The mediator has no investigative powers but, with the consent of parties, may hear any person, who must agree to be heard. The judge may put an end at any time at the mediation process, on his/her own motion or on the request of a party or the mediator. The judge fixes the remuneration of the mediator, who is paid by the parties.

Conciliation and mediation may also be done outside any judicial proceedings.[8]

The participatory procedure (procédure participative) is an agreement concluded by the parties, in which they commit themselves to act jointly and in good faith to the amicable resolution of their dispute or to the instruction of their dispute.[9] A registered lawyer must assist each party. If the agreement is concluded before the filing of a claim in front of the court, the claim is not admissible.

Once the parties have reached an agreement, any of the parties may ask the judge to homologate it.[10] The agreement is then enforceable. The possibilities to challenge the agreement are limited and correspond to actions open to challenge contracts: for instance, a nullity action for vitiated consent (vice de consentement) or lack of capacity. All other legal challenges, in particular those open to challenge judgments, are excluded.

The criticisms addressed to Alternative Dispute Resolution are related to the fact that judicial conciliation is underfunded by the State. Conciliators are volunteers and there is a lack of them to handle all conciliation processes. To that regard, the “just reason” for the claimant not to have recourse to Alternative Dispute Resolution before filing a claim could be the impossibility to meet the judicial conciliator within a reasonable amount of time, given the nature and the implications of his/her claim.[11] On the opposite, mediation and participatory procedure are costly for the parties, who have to pay the mediator and their lawyers in the participatory procedure. If, at the end of the process, they do not reach an agreement, they just have lost time and money, before bringing their claim to the court.

Note that next to Alternative Dispute Resolution in relation to civil procedure, alternatives to criminal prosecution have existed in France since a law nr 93-2 of 4th January 1993 reforming criminal procedure introduced criminal mediation. Since then, they have continued to increase (penal composition, penal settlement, judicial agreement in the public interest). According to the key figures for the justice system in 2019, alternative measures account for 40.2% of the criminal response rate (637,760 alternatives in 2018).[12]

3.4. Simplification of law and by-passing legal processes

In some limited fields, specific processes have been established to simplify the law and provide citizens with a more direct answer. This has mainly happened for traffic accidents and divorces.

In traffic accidents, a law enacted in 1985,[13] called the “Badinter law”, favours the indemnisation of victims, especially pedestrians, who have only to prove that a car is involved in an accident to obtain compensation. Drivers can almost never oppose the fault of the victim to lessen damages.

Since the 1st January 2017, a law[14] has stated that the divorce by mutual consent would take place without any intervention of the judge, even at the stage of the homologation of an agreement. The divorce is stated by private writing, signed by the registered lawyer of each party, and then just registered in front of a public notary.[15] The intervention of the judge is necessary if the ex-spouses have a child who asks to be heard by the judge.

4. ACCESS TO JUSTICE, EQUAL ACCESS TO COURT AND FAIR TRIAL

Access to justice, equal access to courts and the right to a fair trial are protected by Article 6 § 1 of the EConvHR, which is directly enforceable in front of all ordinary, judicial and administrative, courts.[1]

These rights are also protected under the French Constitution. They derive from Article 16 of the Declaration of Human Rights, adopted the 26th of August 1789, which is a substantive part of the French Constitution.

The Constitutional Council has thus consecrated a right to an effective judicial remedy (droit au recours juridictionnel effectif), stating that the legislator is not entitled to significantly limit this right for litigants.[2] The Council has also stated that Article 16 of the Declaration of 1789 ensures the rights of the defence (droits de la défense) and the right to a fair trial (droit à un procès equitable).[3]

Furthermore, combined with Article 6 of the Declaration of 1789, Article 16 of this same Declaration guarantees the principle of equal access to justice (égalité devant la justice). According to this principle, if the legislator may adopt different procedural rules depending on the facts, situations and persons, these differences may not result in unjustified distinctions and litigants must be ensured equivalent guarantees.[4]

It has to be noted that the Constitutional Council has examined the obligation for claimants to have recourse to Alternative Dispute Resolution before bringing their claim (see supra, section 3.3). Given the exceptions stated in the law, the Council has considered that the dispositions challenged comply with the right to an effective judicial remedy and the principle of equal access to Justice.[5]

5. LEGAL AID SYSTEM

5.1. History of legal aid[1]

Judicial assistance has been first recognised in France in an act adopted on 22 January 1851. Any person who could not exercise her rights due to her lack of financial means could ask for this assistance. It was available for any dispute that the judiciary would have to adjudicate. The main objective was to exempt the person from a range of taxes that should have been paid to the Treasury, court fees etc. In addition, lawyers were then not paid for their work, except when the person would obtain from the court cases resources that would have allowed her to proceed in court without judicial assistance.

In 1972 the system was changed, mostly becoming more specific and specialized. The main innovation was then for the lawyers to obtain a right to be paid by the state for their services. This meant that the state was taking over solidarity as the system became then paid through taxes. This system met quickly with success, so much so that lawyers asked for a reform and especially a revision of the fees they received through this system.[2]

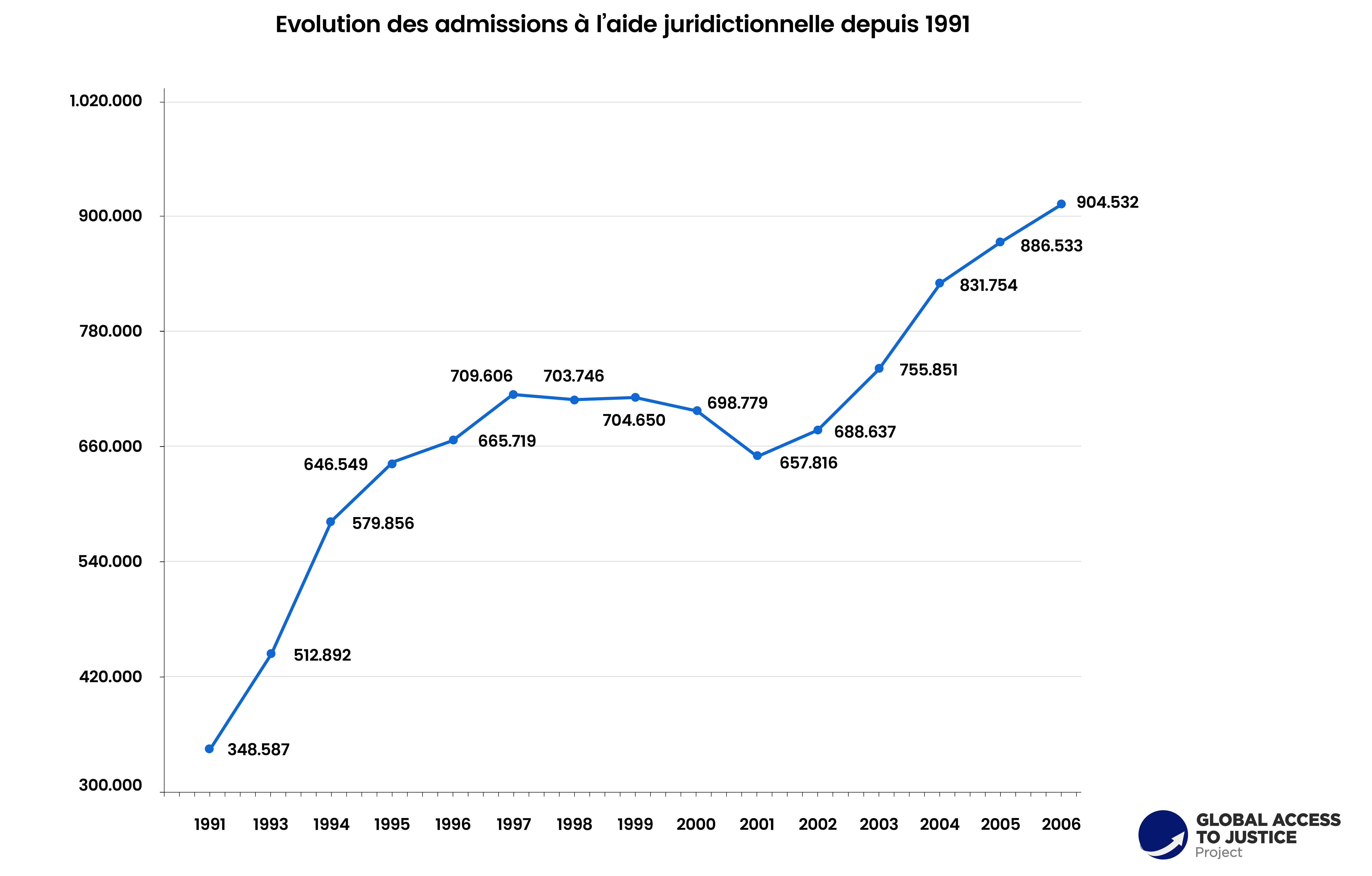

In 1991, the 1972 system was expanded, but the logic remained similar. Since then, the system has only been tweaked in the sense of constant expansion. For instance, it has been extended to cross-border litigations (in some cases)[3] or to judicial mediation;[4] access to law has become provided through an internet website since 2002.

This system keeps meeting with wide success. The Senate presents “[l]egal aid [as] one of the pillars of access to justice, a true democratic imperative”.[5] It has now reached a state of tension between extensive access to justice as a priority and its funding. In 2017, 985,110 cases were admitted for legal aid. This means that the budget spent on legal aid keeps increasing,[6] while lawyers complain that they are not paid well enough.[7] In the context of reforms to the judicial organisation, a range of reports have been adopted, some of them making suggestions in relation to legal aid. Recently, the National Assembly[8] and the Senate[9] have discussed the system of legal aid in order to improve its financial balance.

5.2. Legislative framework for legal aid

The right to exercise a judicial action is provided for in the case law of the Constitutional council[10] and the Supreme Court.[11] More generally, it is also recognised through article 6 of the EConvHR. The European Court of Human rights has recognised that the French system guaranteed substantial protection to individuals against arbitrariness.[12]

The legislative framework is set in an Act nr 91-647 of 10th July 1991. Its first article sets that access to justice and law is guaranteed according to the modalities provided for in this law. It has two main parts. The first part (articles 2 to 52-1) pertains to the regulation of total and part legal aid. The second part (articles 53 to 64-5) goes beyond legal aid to provide for support to access to law, including support for advising and help in non-judicial procedures.

5.3. Institutional framework for legal aid[13]

At the consultative level, the National Council for legal aid (Conseil national de l’aide juridique[14]) was set up in 1991. It is consulted on bill and drafts decrees relating to legal aid, help to access the law and aid for lawyers’ interventions.[15] Its secretariat is run by the Justice Department.[16]

At the level of deciding on legal aid, legal aid offices (bureau d’aide juridictionnelle), set at each judicial court of first instance (tribunal judiciaire) make decisions on legal aid applications. The only exception to this relates to cases to the Supreme Court (Cour de cassation) and the Supreme administrative Court (Conseil d’Etat), which have each their own system. The legal aid office may be subdivided in sections: one general and three specialised ones (for appeal courts, administrative courts or administrative courts of appeal).

Each office is chaired by a judge, who is depending on the case a member of the judicial court of first instance (tribunal judiciaire), of the appeal court (cour d’appel), of the Supreme Court (Cour de cassation) or of the Supreme administrative court (Conseil d’Etat). S/He is appointed by the chair of these courts.

Each office and section includes the chair, two civil servants (one from the departmental or national tax services and one from social services), two representatives from the legal profession (depending on the office they are either a lawyer, a judicial officer (huissier de justice) or a lawyer to the special bar for the Supreme Court and the Supreme administrative court – these are appointed by their professional associations) and a representative for users (appointed by the departmental body for legal aid).[17] The statutory and regulatory framework does not define any managerial roles for the chair of the legal aid office. It only provides that her presence is mandatory for any decision taken on legal aid application (with that of at least two other members[18]). In case of a tie vote, the chair’s one is overriding.[19] When cases are not especially difficult, the chair (of the office or the division) can take decisions on her own.[20]

The legal aid office is run by the court clerk of the court where the legal aid office has its seat – under the supervision of the chair.[21]

The criteria for accepting an application for legal aid are set in the 1991 statute and its decree. Overall, 90 % of the applications (at the level of first instance cases) are granted.[22] The following chart shows the overall evolution of admission for the period 1991-2006.[23] Since then, the overall number seems to keep steadily increasing, but has not quite reached 1,000,000 of admitted cases.

Chart 6. Evolution of the number of legal aid cases since 1991

Once the office has accepted the application, the Treasury pays the sums calculated as per the statutory framework and the tariff to the applicant. A calculation tool is available on-line.[24]

The legal aid office does not provide alternative dispute resolution services (conciliation, mediation etc.), but legal aid is also available for alternative dispute resolution services.[25]

At the level of delivery of legal aid, lawyers are the ones providing their services to legal aid recipients. The principle is that the legal aid recipients have the right to choose their lawyers freely.[26]

5.4. Legal aid budget

Since 2015, the funding of the legal aid comes from two main sources: the state budget (for ca. 80 %) and non-budgetary sources (i.e. specific tax on certain acts and contracts of insurance for legal protection – accounting for less than 20 %).[27] Legal aid is a special component of the annual justice budget (under the programme « Accès au droit et à la justice »[28]).

The legal aid budget is set through the normal decision-making process for the state budget as provided for in the Constitution.[29] Bills tabled by the Government are discussed by the Chambers.[30]

In practice, the state grants yearly a provisional budget to each local fund attached to bar associations (caisses des règles pécuniaires des avocats) based on the sums spent in previous years. This provisional budget is adjusted according to the actual sums granted in legal aid admissions.[31]

In 2008 the budget for legal aid accounted for 4.9 % of the budget granted to the Justice Department with 318.2 millions d’euros.[32] Since then, the nominal amount has overall been increased with a peak in 2012 and then a sharp fall in 2013, followed by a steady increase again.

Chart 7. Budget/year for legal aid since 2010[33]

| Year | Budget (in euro) |

| 2010 | 329 574 190 |

| 2011 | 369 000 000 |

| 2012 | 384 335 000 |

| 2013 | 318 195 654 |

| 2014 | 345 406 000 |

| 2015 | 331 658 936 |

| 2016 | 330 748 321 |

| 2017 | 364 196 004 |

| 2018 | 395 793 007 |

| 2019 | 423 716 957 |

The state attempts to rein in the funding of legal aid through the general budget. It is looking for alternatives, such as user charge provisions (ticket modérateur), the improvement and rationalisation of the management of the legal aid, the strengthening of mechanisms for calling in the insurance for legal protection,[34] and the improvement of measures for the state to recover monies (against the party who does not benefit from legal aid; against the beneficiary of legal aid who lost her case in some instances provided by the law; against the beneficiary of legal aid that has been withdrawn).[35] Equally discussed are the incitation given to lawyers to waive their right to be paid by the state,[36] and the oiling of the interactions between the insurance for legal protection and legal aid.[37]

5.5. Legal aid providers

Any lawyer admitted to practicing to the bar can provide legal aid. Recent statistics on the lawyers who undertake legal aid cases are not available. However, in 2006 the National Bar Council noted that half of the French lawyers were involved in legal aid cases, with a fair allocation across the national territory.[38] Nothing suggests that this trend has changed since 2006.

Lawyers are paid according to a tariff for the various acts and procedures that they can undertake;[39] this tariff is periodically revised. As there is no similar tariff for non-legal aid cases, it is difficult to make any relevant comparisons. French lawyers keep complaining that overall many acts are under-paid, while a minority of them may be over-paid.[40]

Lawyers providing legal aid remain subject to their code of ethics; they are not supposed to receive or follow external guidelines relating to the course of their procedures. Equally, they do not enjoy special rights during the performance of their legal aid procedures.

5.6. Quality assurance

Any lawyer admitted to practicing to the bar can take on legal aid cases. All lawyers are subject to professional training over the course of their career (twenty hours a year[41]). In case of problems with their lawyers, legal aid recipients may – as any other client – complain to the bar association.[42]

There is no general or systematic satisfaction survey, questionnaires or processes available. But a website is dedicated to the general users’ satisfaction with public services, and one part of it pertains to justice.[43]

5.7. Criminal legal aid

5.7.1. Scope of criminal legal aid

Criminal legal aid is provided for by Act nr 91-647 of 10th July 1991 relating to legal aid. It is a financial aid granted to litigants whose income is insufficient to access justice in France. It bears, in whole or in part, the costs of the procedure and expertise, and the lawyer’s fees, the aid being paid directly to the latter. It does not depend on the offense in question.

During the investigation phase, only police custody is paid by the State without means test. Other measures requiring the presence of the lawyer may be eligible for legal aid but subject to means (e.g. assistance by the lawyer during the hearing of the free suspect, hearing of the victim). The maximum income to benefit from the total legal aid is around 1,000 euro per month. Lawyers must agree to work under legal aid.

Legal aid applies, subject to a means test, to all stages of the criminal trial (prosecution, investigation, judgment). It also applies, subject to a means test, during the appeal procedure and during the criminal enforcement phase.

Legal aid, subject to the same means test as for offenders, is available for victims of crimes,[44] but not for witnesses.

5.7.2. Eligibility criteria for criminal legal aid

The criteria for awarding legal aid are exclusively financial and do not depend on the offense in question. In 2019, the household resources must not exceed 1,031 euro to benefit from full legal aid and must be between 1,032 euro and 1,546 euro to be granted partial legal aid. Household having resources higher than 1,546 euro are not eligible to legal aid.[45]

In the case of dependents, the amount of the ceiling increases by 186 euro for one dependent, and 371 euro for two dependents, then by 177 euro for more (if two people are dependent, the total assistance ceiling will increase from 1,031 euro to 1,402 euro).

The recipient of legal aid services in criminal matters may have to contribute to the cost of providing these services if the ceiling on his income exceeds 1,031 euro. In this case the aid will only be partial (between 15% and 85%). Only procedural acts (expertise, investigation, witness summons, translation costs, etc.) will be paid for by the State. The other costs (bailiff, lawyer…) will be covered according to the percentage of coverage.

The recipient of legal aid in criminal matters does not have to reimburse in principle the amount to the aid provider. If s/he loses the trial, legal aid does not provide for the payment of his/her conviction (criminal fine or damages). If the defendant wins his/her trial and obtains significant financial resources, then his/her lawyer can ask him for fees, or even the withdrawal of legal aid.

5.8. Civil legal aid

5.8.1 Scope of civil legal aid

The statutory framework provides for the right to civil legal aid as mentioned above under section 5.2. Civil legal aid is provided for all cases, i.e. administrative law, family law, labour law and immigration cases.[46] It covers legal assistance. Civil legal aid provides legal representation at all instances, first instance, appeal and cassation. Precise official statistics on civil legal aid are not available. However, one out of four cases in civil litigation is supported by civil legal aid. The available statistics do mention that civil legal aid pertaining to asylum and immigration is low.[47]

5.8.2 Eligibility criteria for civil legal aid

To be eligible for civil legal aid, the applicant[48] needs to meet economic vulnerability criteria. In particular, two cases need to be distinguished. If the applicant has an income of less than 1,031 euro/month, s/he is eligible for a total civil legal aid. If the applicant has an income between 1,031 euro/month and 1,546 euro/month, s/he is eligible for a partial legal aid.[49] These amounts are increased for each dependant (186 euro for the first two dependants and 117 euro for the other ones). As a matter of principle, legal aid is available in any matters, contentious or non-contentious in front of any French court.[50]

Specific attention is given to victims of violence. Victims of crimes against life or the physical integrity do not have to justify their resources (nor their right-holders).[51] There is no condition of residency for victims of marital violence.[52]

Civil legal aid is available for French nationals, EU nationals as well as non-(EU) nationals (who are usually resident in France), including in asylum and immigration cases. It is also available for French residents who seek to start judicial proceedings in another State of the European Union.[53] Specific adaptations for the cases of overseas territories have been provided for.[54] Legal aid may also be “exceptionally” granted to applicants who do not meet the residency condition, when “their case is especially interesting with respect to the subject-matter of the litigation”.[55]

The statutory framework provides for an assessment of the case before legal aid is granted.[56] This does not apply however to a range of people (e.g. the defendant in a civil or criminal case, the civilly liable person, etc.). At the level of cassation, civil aid is not granted if no serious argument can be invoked.[57] However, official reports mention that this assessment is not carried out in practice.[58] Furthermore, the statutory framework provides for withdrawing legal aid when the financial circumstances of the applicant have changed during the proceedings, when legal aid has been obtained by fraud or when the judicial proceedings have been found abusive.[59] However, this is barely ever applied.[60]

Reimbursement of (part of) the legal aid is provided in some cases in the statutory framework. It provides that the judge may ask the reimbursement of a part of the legal aid to the state in the case of the claimant who has obtained a partial legal aid and who lost his/her case or has been condemned by the judge to pay the court fees.[61] Legal aid can also be recovered against the losing party who does not benefit from legal aid.[62] In practice, the treasury effectively recovers 60% of the sums due under this system. There are 33,000 cases roughly a year, for sums amounting roughly on average to 500 euro.[63]

5.8.3 Process for obtaining civil legal aid

The process for obtaining civil legal aid is initiated by filling a form,[64] including a series of documents to evidence some information (such as the identity, the financial resources and the non-coverage of the proceedings by an insurance provider). These documents have to be submitted at the first instance court competent with regard to the residency of the applicant.

The legal aid office makes a decision on the application. If legal aid has been rejected or only partly granted, the applicant may appeal the decision to the chair of the court of appeal, the chair of the Supreme Court, the chair of the administrative court of appeal or the chair of the Administrative Supreme Court, depending on the case.[65] The statutory framework does not specify the grounds available for this appeal. The decisions following this procedure cannot be appealed further.[66]

5.9. Holistic legal services

A number of “points of single contact” (guichets uniques) exists. For instance, at the level of the courts themselves, a service for the litigant (service d’accueil unique du justiciable) is available, where litigants can go to be better directed in the different legal proceedings.

5.10. Legal aid before regional human right mechanisms

The French system of legal aid does not provide legal aid for judicial challenges to the regional human rights mechanisms (either the Court of Justice of the European Union or the European Court of Human Rights).[67]

6. COSTS OF RESOLVING DISPUTE WITHIN THE FORMAL JUDICIARY MACHINERY

6.1. Overview of judicial costs for litigants

Since 1977, the principle in France is that the public service of justice is free. However a series of costs are incurred in practice. In civil litigation cases, the costs directly related to the proceedings are referred to as dépens. They are listed in the Civil Procedure Code.[1] They are as follows:

– duties, taxes, fees or emoluments collected by the tax administration or by the clerks of the commercial courts;

– costs of translation of documents;

– witness fees (travel, subsistence, etc.);

– remuneration of technicians (experts, consultants, etc.);

– remuneration of public and judicial officers, in particular bailiffs (summonses, service of judgments, seizures, etc.);

– remuneration of the lawyer excluding fees (pleading fees, emoluments and various duties or costs at the regulated rate – they are so-called débours tarifiés);

– compensation paid by the State to the lawyer of the party receiving legal aid;

– costs incurred in serving a document abroad;

– interpreting and translation costs relating to investigative measures carried out abroad;

– costs of social inquiries ordered by the family court or guardianship judge;

– remuneration of the person designated by the judge to hear the minor in proceedings concerning him or her;

– costs relating to measures, investigations and examinations required in connection with the wrongful removal of children internationally.

The calculation of these costs depends from case to case. For instance, bailiffs’ acts (summonses, service of judgments, seizures, etc.) are subject to a registration fee (droit d’enregistrement), which is periodically updated.[2] The costs of experts appointed by the judges are determined by the judge. These costs will be determined according to the work undertaken, the time constraints and the quality of the work.

The judge is obliged to say who has to pay the costs.[3] It is usually the losing party who must pay those costs. In addition to the costs, the judge can order one party to pay the other party an amount called non recoverable costs (frais irrépétibles). These include lawyers’ fees, travel and accommodation costs for the purpose of the trial.

If the winning party pays his/her lawyer through legal aid, the court may order the losing party to pay the winning party’s lawyer additional fees.

In all cases, the judge takes into account the fairness or economic situation of the losing party.[4]

In criminal litigation cases, the state pays for the costs of the trial. However, when the defendant is convicted, s/he will have to pay a fixed fee for the procedure.[5]

6.2. Exemptions from judicial costs

The judge can for reasons grounded in the fairness or the economic situation of a party exempt her from paying the costs.[6]

The recipient of the legal aid may be condemned to pay the costs incurred by his/her opponent, but s/he only bears the costs really incurred by him/her. In any case, the judge may leave a part of the costs to be borne by the state.[7]

The recipient of the legal aid is exempted from the fees born in relation to bailiffs’ acts (summonses, service of judgment) relating to the procedure for which s/he obtains the legal aid.[8] If there are disputes arising from this, an appeal to the head of the court in relation to which the problem arises or to the head of the judicial court can be lodged.

A series of other fees are also exempted, such as the registration fees. The exemption is final and will never be recovered, even if the recipient of the legal aid has to bear the costs of the proceedings.[9]

6.3. Mechanisms to reduce costs by variations to courts and procedures

In January 2020, a reform of the judicial system has been initiated, which includes courts dealing with small claims. The main concern of these reforms is not geared to the reduction of costs for litigants. A website, « DemanderJustice.com », had been initiated privately in 2012 for small claims (less than 10,000 euro) and for which no legal representation was compulsory. This project had been challenged by professional organisations of lawyers. Yet, the Supreme Court accepted that the services provided through this website did not amount to an illegal exercise of the legal profession.[10]

However, recent legislative reforms seem to pursue other, maybe even contradictory, objectives. First, it makes representation by lawyers generalised.[11] Secondly, it provides for a dematerialised process of small claims in the day-to-day life. It sets up a new national court for the dematerialised process for orders for payment.[12] The reforms date back from 2019, with an entry into force on 01.01.2020 for the first aspect and an entry into force still to be scheduled for the second aspect.

Additionally, previous reforms had dealt with the digitalisation of the management of judicial costs (such as translation, interpretation, medical expertise). It is managed through an internet portal. The primary objective is not the reduction of costs for litigants, but the better management of these judicial costs may lead to such a reduction.[13]

7. THE PROTECTION OF DIFFUSE AND COLLECTIVE RIGHTS

The right to initiate a judicial action is traditionally seen as a highly individual right in French civil procedure.[1]

However, recent reforms have challenged this trend. Since 2014, an action is open for consumer associations,[2] in order to obtain damages for individual damages suffered by consumers, placed in a similar or the same situation and with a common cause, i.e. a violation by one or the same professionals of their legal or contractual duties – when this has been caused by the sale of goods, the furniture of services or the location of a real estate property; or when the harm is the result of anti-competitive practices (in the sense of art. 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning European Union and similar domestic provisions). A similar action is also open to certified associations in relation to environmental matters.[3]

Consumer (resp. environmental) associations are the only entities allowed to initiate proceedings in consumer (resp. environmental) matters. In that sense, the French system is not a collective action, but a specific action, whose effects may benefit a number of consumers. In practice, this action does not seem to have been very often used. Indeed, the consumer action can only allow for the compensation of economic damages and not moral damages. Furthermore, associations have limited budget capacities to initiate this action. Finally, mediation in consumer cases has been introduced around the same time, meaning that disputes are resolved in a different way.

However, it is also possible for individual actions to join to an on-going individual action, thanks to procedural rules of connectedness (connexité). Online platforms have now developed where lawyers publish their intention to start judicial proceedings and invite individuals to join in.[4] In these cases, legal costs can be kept low. However, the cases when such a procedural tool can be used are limited because of conditions of sufficient similarities between the cases.

In administrative law, the judicial proceedings are traditionally understood as an action against an illegal administrative decision (a decision taken by a public authority which has exceeded its legal powers or breached procedural requirements). The grounds for admissibility were traditionally understood widely, making it nearly an action popularis (if not quite so). The administrative process was indeed very much understood as an objective litigation, where the litigant did not need to demonstrate to have a subjective right in relation to the administrative decision s/he challenged.

Since 2016, new collective actions are available for individuals who are victims of the same harm by a professional.[5] The claimants can then bring a collective action, they can file one single claim with one single lawyer. Two class actions are open in the administrative justice system: a “group action” (action de groupe)[6] and an action for recognition of rights (action en reconnaissance de droits).[7] These collective actions allow an association (or a professional body) to initiate an action at the level of principle to obtain a declaration of liability or of right, which suspends the time limits to the benefit of all potential beneficiaries of the judicial decision.

The action for recognition of rights can be initiated to obtain the payment of an amount that is legally due or the reimbursement of a sum illegally claimed. They cannot aim to obtain the recognition of a harm.

The group action can be initiated when a number of individuals, in a similar situation, have been harmed by a public body or a private entity pursuing a public service, when the cause is the same breach of its legal or contractual duties. This action can be initiated to make the harm stop, to obtain compensation from the public body or the private entity or both. This action can be initiated in five fields:

(i) discrimination suffered by citizens;[8]

(ii) discrimination suffered by employees of a public employer;[9]

(iii) breach of the environmental legislation;[10]

(iv) fault in the production, provision or delivery of a health product;[11]

(v) breach of norms protecting personal data.[12]

The interest required to initiate the judicial proceedings depends from case to case:

(i) for discrimination: associations fighting discrimination or working in the field of disability (with at least five years of existence);

(ii) discrimination by a public employee: trade unions of civil servants or judges and associations fighting discrimination or working in the field of disability (with at least five years of existence);

(iii) environment: association accredited for protecting victims of bodily harms or economic interests and associations accredited for protecting the environment;

(iv) health matters: associations accredited of users of the health care system;

(v) personal data: associations of protection of privacy and personal data (with five years of existence minimum); associations accredited for protecting consumers, trade unions of civil servants, judges and employees.

Administrative class actions need to be listed on the website of the Supreme Administrative Court to allow potential beneficiaries to be kept informed of their evolution. However, the list only mentions three such actions so far.[13]

8. PROFESSIONAL LEGAL ETHICS

French lawyers are self-regulated through bar associations.[1] All registered lawyers are subject to professional ethics. These are codified in the National Internal Regulation (Règlement intérieur national de la profession d’avocat);[2] a global code governing lawyers’ conduct. There is a specific part linked to a European code of legal ethics.[3]

These professional ethics are taught to lawyers, directly by registered lawyers, when they follow the formation in the specific regional school (Ecole de formation du barreau), necessary to become a registered lawyer. Professional ethics is the major oral examination at the end of such formation, based on courses and internships. Once they have succeeded in their formation and after having found a collaboration in some law office or after having opened their law offices, registered lawyers have to take the following oath:

« Je jure, comme avocat, d’exercer mes fonctions avec dignité, conscience, indépendance, probité et humanité », which may be translated as « I swear, as a lawyer, to undertake my functions with dignity, conscience, independence, probity and humanity ».

During the first two years of them exercising their legal profession, lawyers are required to undertake at least ten hours of continuing professional development on professional ethics.[4]

There are no official statistics about the breaches of professional legal ethics by lawyers. However, some limited research has shown that the rate of professional sanction was extremely low: less than one lawyers out of 1,000 are sanctioned at regional level, at less than four lawyers out of 1,000 in Paris.[5] However, when there is a sanction, it is usually a relatively serious one, leading the lawyer to be banned from practicing law at least for a while. Half of the breaches of professional ethics relate to breach of « délicatesse/moderation ».[6] In addition, lawyers are subject to criminal and civil liability.

Lawyers lobby to protect legal aid as they see it as the core of their professional ethical duty.

9. TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE

The Justice Department has started a series of reforms seeking to encourage the dematerialisation of judicial proceedings. For instance, it launched a portal « Justice.fr » where the litigant can find a series of general information (including on legal aid) and can follow the course of his/her judicial action – provided s/he agreed with dematerialisation.

However, discussions in the legal scholarship are cautious about these developments, highlighting the risks of deshumanisation of justice proceedings and the loss of social interactions through legal professions.[1] Furthermore, a wide range of the population may end up being excluded from these technological innovations. The French Ombudsman has carried out a survey of the population without access to computer and the Internet: he found that 20 % of the French population did not have a computer and 27 % no smartphone, in addition to individuals leaving in rural areas with poor internet connection.[2] On a more positive note, his report also discusses the widespread use of technology for a variety of public services (e.g. tax-on-line, health insurance or children allowances).

Lawyers are generally well equipped when it comes to using technology for business purposes. An association of “digital lawyers” has been set up in 2016 to reflect on the changes for the professions thanks to the development of technological innovations.[3] In 2018, the National Bar Council (Conseil national des barreaux) has adopted a plan to finance the use of digital technologies by lawyers.[4] It has also developed a platform helping citizens to find lawyers[5] and a e-bar as a virtual network for lawyers.[6]

Digital technology is used to help citizens navigate services. One example is the portal « Justice.fr » mentioned above; other examples include websites for social services for students[7] or for access to social support[8]. More generally, a website provides a general map of the public services available in France (https://www.service-public.fr/). It is for instance possible to get an estimation of the alimonies one may be entitled to (as an information as the judge can assess matters differently)[9] or the student’s allowances one is entitled to.[10]

Self-represented litigants can find information online through « Justice.fr » (a publicly run website) and through « DemanderJustice.com » (a privately-run website). However, the constant extension of the obligation for litigants to be represented by a lawyer makes these tools relevant only in a small number of cases.

Reforms regarding online dispute resolutions, or at least making litigations less material, are on-going. However, questions arise with this new approach as it limits the sense of proximity with which justice is normally associated in France.[11]

10. UNMET LEGAL NEEDS

To our knowledge, there has been no recent countrywide needs assessment in France. However, the French Ombudsman published an opinion in 2019 where he stated the difficulties for some groups of people to have access to legal aid. He especially flagged that in some cases, people in a situation of extreme vulnerability are not in a position to demonstrate in a suitable way their lack of resources (e.g. inhabitants of slum areas cannot get an official document demonstrating that they do not pay taxes or people who recently arrived in France, and hence are not entitled to legal aid).[1]

Public services desertification has been a core concern of the “yellow vests” demonstrations in 2019, referring to the fact that isolated areas and rural areas can be disconnected from urban areas and thus less well provided in public services. Initiatives such as « France Services » are developed to address this problem. However, legal aid is not directly affected by this desertification in the sense that it is managed by courts at first instance, which are reasonably well spread over the country and that services such as « maison de justice »[2] are organised across the country to provide information on access to justice and law.

As a whole, there is no area of the territory where the law is not enforced.

11. PUBLIC LEGAL EDUCATION

In terms of public legal education, the French school curriculum (for children between 6 and 16 years old) includes a shared foundation of modules, one of them relating to the development of the person and the citizen (formation de la personne et du citoyen). In this module, the general values and principles of the French Constitution are taught.[1] This means that the teaching pertains mostly to civism, as a way to fight discrimination, intolerance, racism and antisemitism.[2] Among the various actions that schools are encouraged to take, no specific attention seems to be given to the judicial system per se or the way in which the law works as a technique or a system.[3]

12. GLOBAL EFFORTS ON ACCESS TO JUSTICE

France is a member of the Council of Europe and the European Union. It is thus involved in the European efforts to promote access to justice that these two international organisations develop, especially the CEPEJ[1] and the European Agency for Fundamental Rights.[2]

Special attention is given to access to justice in environmental matters, in accordance with the Aarhus Convention.[3]

France is actively involved in the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in general (see for instance its engaged support for a Global Environmental Pact[4]). French policy of development assistance focuses on 19 countries and four objectives, one of them being democratic governance and rule of law, i.e. Sustainable Development Goal 16.3.[5]

13. CONCLUSIONS

Overall, the French legal aid system is regulated by an Act dating from 1991, many times adapted since then. At the level of principle, the system may seem to provide legal aid in many areas of civil, administrative and criminal law at all levels of the justice system. There are however a series of practical and technical aspects that seriously limit the coverage of legal aid in France.

First, the revenue threshold to be eligible to legal aid is very low, with only citizens living under the poverty threshold or close to it eligible to it. Secondly, lawyers say that many activities that they have to perform in legal aid cases are not remunerated adequately, calling into question the reliability of the legal services provided with the support of legal aid. Finally, legal aid is not available for bringing a case to the European courts (either the Court of Justice of the European Union or the European Court of Human Rights).

Overall, the French system of legal aid is seeking to strike a balance between a wide access to justice and the financial sustainability of the legal aid system. Discussions about how to reach this balance have been ongoing for at least ten years, and they involve the very definition of the role of the “barrister” (avocat) in the French legal system: now, legal representation has been extended and the legal professions seek to define their own future at times when digital services are changing how the law works, citizens’ expectations about the law, the provision of legal services and the ways in which the justice system is operating. All these changes are very much behind the strike that lawyers have taken in early 2020 in relation to their retirement system.[1] The Justice Minister has set up a committee, chaired by a former Justice Minister, Mr Perben to discuss the future of the legal profession, including the system of the legal aid.[2]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Constitutional, statutory and regulatory norms

- Declaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen: Art. 6; Art. 16

- French Constitution 1958: Art. 2 ; 39 ; Art. 42 ; Art. 47 ; Art. 49 ; Art. 64 ; Art. 68

- Administrative justice code: Art. L. 77-10-1 and following ; Art. L. 77-11-1 ; Art. L. 77-12-1 and following ; R. 77-10-1 dd; R. 77-12-1 and following ; Article R431-2 ; Article R431-3

- Civil code: Articles 229-1 and following ; Article 2062

- Civil Procedure Code : Article 21; Article 128 ; Article 129 ; Article 131 ; Articles 131-1 and following ; article 131-12 ; Article 695-1°; Article 695-2°-12°; Article 696 ; Article 700; Article 750-1 ; Article 760 ; Articles 761 ; Article 1530 and following ; article 1534 ; Article 1541 ; Article 2062 and following ; Article 2066

- Consumption code: Art. L622-1 and L623-1

- Environmental code: Art. 141-1 ; Art. L. 142-3-1

- General Taxation Code: Article 302 bis Y

- Public health code: Art. L. 1143-1

- Loi nr 2019-222, 23 March 2019 de programmation 2018-2022 et de réforme pour la justice

- Loi nr 2017-242, 27 February 2017 portant réforme de la prescription en matière pénale

- Loi nr 2016-1547, 18 November 2016 de modernisation de la justice du XXIe siècle

- Loi nr 2015-990 du 6 août 2015 pour la croissance, l’activité et l’égalité des chances économiques (« Loi Macron »)

- Loi nr 2010-769, 9 July 2010, relative aux violences faites spécifiquement aux femmes, aux violences au sein des couples et aux incidences de ces dernières sur les enfants

- Loi nr 2008-496, 27 May 2008, portant diverses dispositions d’adaptation au droit communautaire dans le domaine de la lutte contre les discriminations

- Loi nr 2005-750, 4 July 2005 portant diverses dispositions d’adaptation au droit communautaire dans le domaine de la justice

- Loi nr 91-647, 10 July 1991, relative à l’aide juridique

- Loi nr 85-677, 5 July 1985 tendant à l’amélioration de la situation des victimes d’accidents de la circulation et à l’accélération des procédures d’indemnisation

- Loi nr 78-17, 6 January 1978 relative à l’informatique, aux fichiers et aux libertés

- Loi nr 71-1130, 31 December 1971 portant réforme de certaines professions judiciaires et juridiques

- Law of 24th May 1872, portant réorganisation du conseil d’Etat

- Décret nr 2019-1333, 11 December 2019 réformant la procédure civile

- Décret nr 2019-965, 18 September 2019, portant substitution du tribunal judiciaire au tribunal de grande instance et au tribunal d’instance dans les textes réglementaires en application de l’article 95 de la loi n° 2019-222 du 23 mars 2019 de programmation 2018-2022 et de réforme pour la justice

- Décrets d’application nr 2019-912, nr 2019-913, nr 2019-914, 30 August 2019

- Décret nr 2016-1876, 27 December 2016, portant diverses dispositions relatives à l’aide juridique

- Décret nr 2005-790, 12 July 2005, relatif aux règles de déontologie de la profession d’avocat

- Décret nr 91-1266, 19 December 1991 portant application de la loi nr 91-647 du 10 juillet 1991 relative à l’aide juridique

- Décret nr 78-381, 20 March 1978 relatif aux conciliateurs de justice

- Ordonnance nr 58-1270, 22 December 1958 portant loi organique relative au statut de la magistrature

- Arrêté, 17 October 2016, fixant le programme et les modalités de l’examen d’accès au centre régional de formation professionnelle d’avocats

Case law

European Court of Human Rights

- ECtHR, Moulin v. France, 23 November 2010 (Application no 37104/06)

- ECtHR, Essaadi v. France, 26 February 2002 (Application no 49384/99)

Constitutional Council

- Decision nr 2019-803 QPC, 27 September 2019, Mrs Fabienne V.

- Decision nr 2019-801 QPC, 20 September 2019, Mr. Jean-Claude F.

- Decision nr 2019-778 DC, 21 March 2019

- Decision nr 2018-741 QPC, 19 October 2018, Belkacem B.

- Decision nr 2017-680 QPC, 8 December 2017, Union Syndicale des Magistrats

- Decision nr 90-285 DC, 28 December 1990

- Decision nr 88-248 DC, 17 January 1989

- Decision 80-119 DC, 22 July 1980

Supreme Court

- 21 mars 2017, nr 16-82.437

- , 2nd, 21 June 2012, nr 12-40.036

- mixte, 24 May 1975, nr 73-13556 (Jacques Vabre)

Supreme Administrative Court

- Assemblée, 20 October 1989 (Nicolo)

Books, articles and papers

- Babonneau, « Grève des avocats: les propositions de la Chancellerie entre audace et réchauffé », Dalloz Actualités, 1st March 2020

- S Ben Hadj Yahia, « L’action de groupe », Répertoire de procédure civile, June 2015 (updated May 2017)

- Chaserant and S. Harnay, « La déontologie professionnelle en pratique. Enquête sur l’activité disciplinaire de la profession d’avocat », (2016/1) 16 Revue Française de Socio-Économie, 119-139

- -S. Chavent-Leclère, « La transaction existe-t-elle en droit pénal ? », in La transaction dans toutes ses dimensions, (Dalloz, coll. Thèmes & commentaires 2006) 147

- Constantinesco and S. Pierré-Caps, Droit constitutionnel (Paris Puf 2013, 6th edn)

- Coustet, « Injonction de payer : la future procédure dématérialisée suscite l’inquiétude », Dalloz Actualité, 19 April 2018 (available https://www.dalloz-actualite.fr/flash/injonction-de-payer-future-procedure-dematerialisee-suscite-l-inquietude)

- Doliveux, « Réforme des alternatives procédurales : de (grands) petits pas vers un nouvel équilibre de la procédure pénale ? », Note sous Loi numéro 2019-222 du 23 mars 2019 de programmation 2018-2022 et de réforme pour la justice, Journal officiel numéro 0071 du 24 mars 2019, La Gazette du Palais, 29, 71-74

- Fricero (dir.), Le guide des modes amiables de résolution des différends (MARD) (Paris Dalloz 2017-2018, 3rd edn)

- Gerphagnon, « Aide juridique », Répertoire procédure civile, June 2015, updated 2019

- Giacopelli, « Les procédures alternatives aux poursuites . Essai de théorie générale », (2012) 3 Revue de science criminelle et de droit pénal comparé, 505-521

- -L. Gillet, « L’aide juridictionnelle: du financement introuvable au financement retrouvé », 2016 (1) Les Cahiers de la Justice, 131-135

- Guettier, « Chapitre 1152 – Action en réparation devant la juridiction administrative », Dalloz Action – Droit de la responsabilité et des contrats

- Guinchard, A. Varinard and T. Debard, Institutions juridictionnelles (Paris Dalloz 2019, 15th edn)

- Ludwiczak, « Procédures alternatives aux poursuites et action publique : entre apparence de conformité et quête de cohérence », JCP G Semaine Juridique (édition générale), 26 December 2011, 52, 2568-2570

- -B. Perrier, « Alternatives aux poursuites : l’orthodoxie juridique face à l’opportunité pratique », (2011) Recueil Dalloz, 2349-2350

- Robiliard, « Rapport d’information », AJ pénal 2019.413

- Salas, « Dossier: Les défis de la justice numérique – Data, écrans, prévisions », Les cahiers de la justice 2019, 201

- Steff, « La protection de l’accès au juge judiciaire par les normes fondamentales », (2017) Les Annales de droit, 233-253

- Véricel, « La disparition de la justice de proximité – (Loi n° 2019-222 du 23 mars 2019 de programmation et de réforme pour la justice) », (2019) Recueil Dalloz 2019, 1772

Official reports

- Assemblée nationale, rapport d’information sur l’aide juridictionnelle, présenté par P. Gosselin et N. Moutchou, n°2183, 23 July 2019

- CEPEJ, Groupe de travail sur la qualité de la justice, Rapport – La réalisation d’enquêtes de satisfaction auprès des usagers des tribunaux des Etats membres du Conseil de l’Europe, 2010

- Conseil national des Barreaux, Les alternative business structures mettent en danger les principes essentiels de la profession d’avocat et les intérêts du public, 15-16 June 2012

- Conseil national des Barreaux, Observatoire – Statistiques – Aide juridictionnelle, 2006

- Council of Europe , European Court of Human Rights , European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Handbook on European law relating to access to justice, 2017

- Cour des comptes, La gestion et le financement de l’aide juridictionnelle et des autres interventions de l’avocat, 23 December 2016, S2016-4074

- Défenseur des droits,Dématérialisation et inégalités d’accès au service public, 2019

- Défenseur des droits, Avis du Défenseur des droits nr 19-09, 27 May 2019

- Environmental Research of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety, The legal debate on access to justice for environmental NGOs, 2017

- Ministère de la Justice, Les chiffres-clés de la justice en 2019

- Rapport sur les professions du droit, 2009 (Rapport Darrois)

- Sénat, Avis au nom de la commission des lois constitutionnelles, de législation, du suffrage universel, du Règlement et d’administration générale (1) sur le projet de loi de finances, adopté par l’Assemblée nationale, pour 2019, VIII, Justice judiciaire et accès au droit, 22 November 2018

- Sénat, Rapport d’information sur l’aide juridictionnelle, fait par S. Joissains et J. Mézard, nr 680, 2 July 2014

- Sénat, Rapport d’information au nom de la commission des Finances, du contrôle budgétaire et des comptes économiques de la Nation (1) sur l’aide juridictionnelle, nr 23, 9 October 2007, 34-37 ; Sénat, Rapport d’information de la commission des finances, du contrôle budgétaire et des comptes économiques de la Nation sur l’aide juridictionnelle, nr 63, 29 October 2008

- Sénat, Rapport d’information au nom de la commission des Finances, du contrôle budgétaire et des comptes économiques de la Nation (1) sur l’aide juridictionnelle, nr 23, 9 October 2007

Internet websites

- Assocation des avocats numériques : https://www.associationdesavocatsnumeriques.fr/

- Conseil national des Barreaux : https://www.cnb.avocat.fr/fr/etats-generaux-de-lavenir-de-la-profession-davocat-0

- Direction du budget : https://www.performance-publique.budget.gouv.fr/

- E-barreau (réseau virtuel des avocats) : https://ebarreau.fr/index.php

- gouv.fr : https://www.etudiant.gouv.fr/pid33629/bourses-sur-criteres-sociaux.html

- France Diplomatie: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/

- Global pact for the environment : https://globalpactenvironment.org/en/ .

- INSEE (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques): https://www.insee.fr/fr/accueil

- Justice Department : http://www.justice.gouv.fr/

- Mes droits sociaux : https://www.mesdroitssociaux.gouv.fr/dd1pnds-ria/index.html

- MySmartcab : https://mysmartcab.fr/christophe-leguevaques/

- National Education Department : https://eduscol.education.fr/

- National School for Judiciary : http://www.enm.justice.fr/

- OECD : https://data.oecd.org/gdp/gross-domestic-product-gdp.htm#indicator-chart

- Observatoire de la liberté religieuse : https://www.liberte-religieuse.org/france/

- Service public : https://www.service-public.fr/

- ThelysConso : https://www.thelys-conso.fr/defense-groupee/

- UNDP : https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home.html

- Vie publique : https://www.vie-publique.fr/

[1] Art. 6 al. 1st Constitution provides for the direct election of the French President; art. 49 al. 1st Constitution provides for the political accountability of the government in the Lower House. Technically the French President has no accountability except the one resulting from election (although art. 68 al. 1st Constitution provides for a form of accountability in specific circumstances, namely that of a “breach to his duties obviously not compatible with the exercise of his mandate”). For a discussion, see e.g. V. Constantinesco and S. Pierré-Caps, Droit constitutionnel (Paris Puf 2013, 6th edn) para 424.

[2] https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3633212 .

[3] Art. 2 al. 1st French Constitution 1958.

[4] https://www.liberte-religieuse.org/france/ .

[5] https://data.oecd.org/gdp/gross-domestic-product-gdp.htm#indicator-chart .

[6] http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/FRA .

[7] See Ministère de la Justice, Les chiffres-clés de la justice en 2019, p. 4.

[8] See Ministère de la Justice, Les chiffres-clés de la justice en 2019, p. 10.

[9] See Ministère de la Justice, Les chiffres-clés de la justice en 2019, p. 15.

[10] Translation into English from : http://www.justice.gouv.fr/organisation-de-la-justice-10031/lordre-judiciaire-10033/ .

[11] Conseil national des Barreaux, Les alternative business structures mettent en danger les principes essentiels de la profession d’avocat et les intérêts du public, 15-16 juin 2012.

[12] Rapport sur les professions du droit, 2009 (« Rapport Darrois »).

[13] Art. 65 Loi nr 2015-990, 6 August 2015 pour la croissance, l’activité et l’égalité des chances économiques (« Loi Macron »).

[14] https://www.cnb.avocat.fr/fr/etats-generaux-de-lavenir-de-la-profession-davocat-0 .

[15] S. Guinchard, A. Varinard and T. Debard, Institutions juridictionnelles (Paris Dalloz 2019, 15th edn) para 185 ff.

[16] https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F15018.

[17] Article 760 Civil Procedure Code and article R431-2 Administrative Justice Code.

[18] Articles 761 Civil Procedure Code and article R431-3 Administrative Justice Code.

[19] Reforms in 2019 extend the principle of mandatory representation by a lawyer except when provided otherwise (Art. 760 Civil Procedure Code).

[20] Constitutional Council, decision 80-119 DC, 22 July 1980.